Q-5. The last second-generation aircraft in combat service with the PLAAF is the Q-5 Fantan. The Q-5 evolved from the J-6, which itself was a Chinese-produced MiG-19; it first flew in 1965 and entered service in 1970. In keeping with what we will see is PLAAF practice, the Q-5—nearly obsolescent already by North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) or Warsaw Pact standards at the start of its operational career in China—has been modified and updated several times over the years. The newest variant, the Q-5L, has been fitted with a conformal belly fuel

tank and a laser designator under the nose, and Chinese Internet photos show it equipped with a targeting pod on a ventral pylon and laser-guided bombs hung on the wings. Despite its age, the Q-5L could be an effective light attack aircraft if employed in a very forgiving air defense environment.

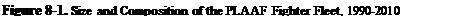

1st Generation

1st Generation

2d Generation 3d Generation 4th Generation

J-7. A reverse engineered MiG-21, the J-7 Fishbed was put into production in the early 1960s, entered PLAAF service in 1965, and has since been produced in a bewildering variety of subtypes.6 It is still the most numerous type of fighter in the PLAAF’s inventory; the latest (and probably last) model, the J-7G, first flew as recently as 2002. In production for nearly 4 decades—a time span that likely will never be approached, let alone surpassed, by another combat aircraft—the J-7 has been improved over time, including several upgrades to its radar, addition of a head-up display (HUD) and other updated avionics, a larger, double-delta wing, and integration of more modern air-to-to air missiles (AAMs), including the infrared (IR)-guided PL-8. Production of the J-7G reportedly continued at least into 2009.

J-8. Originally an enlarged, twin-engine development of the J-7, the J-8 Finback is yet another PLAAF aircraft that has been progressively upgraded since its introduction in 1981.7 A major redesign was undertaken in the late 1980s, which saw the forward fuselage with its MiG-21-style nose intake give

way to one featuring a solid nose—accommodating a more powerful radar— and two lateral air intakes, one on each side of the aircraft. It is this version, the J—8II or J-8B, which continues to serve and has also been the platform for several generations of progressively more capable models. The latest confirmed variant is the J-8F, which has been equipped with new cockpit avionics, more powerful engines, and a probe for in-flight refueling.8 The most significant upgrade is the installation of a newer radar that enables employment of the PL-12 active homing radar-guided “fire and forget” medium-range AAM (MRAAM). Although not as capable as the most modern aircraft in its arsenal, these late-generation J-8s provide the PLAAF another, presumably cheaper, platform capable of using its most up-to-date air-to-air weapons.

JH-7. The JH-7 Flounder is an indigenously designed twin-engine attack fighter that entered PLAAF service by 2004.9 The current production model is the JH-7A, equipped with improved radar, digital flight controls, and modernized cockpit instrumentation. The aircraft’s empty weight has been reduced via utilization of composite materials and the number of stores hard – points increased from 7 to 11. The JH-7A can be equipped with navigation, targeting, and data link pods mounted under the forward fuselage and is capable of carrying a wide array of land attack and maritime strike weapons of both Chinese and Russian origin. It, too, has been photographed carrying the PL-12 MRAAM. There are reports that a second update, the JH-7B—with improved engines and some radar signature reduction—is under development, although no solid evidence of this has yet appeared.

J—10. The J—10 is a single-engine multirole aircraft developed by Chengdu Aircraft Industry Corporation (CAC). First flown in March 1998, the J-10 reportedly entered PLAAF service in 2003. A tailless design with canard foreplanes, the J-10 strongly resembles the cancelled Israeli Lavi fighter though it is unclear how much design assistance, if any, CAC received from either Israel or Russia (although the latter has to date provided the J-10’s engine). It has 11 weapons stations and has been photographed with what appear to be navigation and targeting pods mounted ventrally just aft of the underslung air intake, and with a removable fixed air refueling probe on the starboard side of the fuselage. Around the time that the first J-10s were being deployed by operational units, development began on an upgraded version of the aircraft. Dubbed the J-10B, the new model features a simplified engine inlet ramp that reduces weight and improves the aircraft’s radar signature. The J-10B also adds an electro-optical targeting system (EOTS), visible as a bulge forward and to the starboard side of the canopy. Featuring an infrared search and track (IRST) sensor and a laser rangefinder, the EOTS allows a pilot to passively detect and target enemy aircraft without requiring telltale signals from the J-10’s radar.

Su-27SK/UBK, J-11A. The first variants of the Sukhoi Flanker to join the PLAAF were the single seat Su-27SK and the two-seat operational trainer, the Su-27UBK.10 These were also the first fourth-generation combat aircraft to enter PLAAF service when they appeared in the mid-1990s. Initially, the PLAAF purchased its Flankers from the Russian production line, but these have been supplemented over time by more than 100 aircraft built from Russian-supplied kits by Shenyang Aircraft Corporation (SAC), aircraft that are designated J-11A. Chinese assembly of these J-11A kits was ended about halfway through the planned 200 aircraft run because PLAAF requirements had reportedly evolved such that the single-role air superiority Su-27/SK/J-11A no longer suited the service’s needs. As originally built, China’s Su-27SK/J-11 fighters can carry neither the Chinese PL-12 nor the Russian R-77 (AA-12) active-homing MRAAMs. There are, however, reports that at least some of these aircraft have been fitted with the radar modifications needed to fire the R-77/AA-12. Like the J-10B, all Flankers feature an EOTS mounted in front of the canopy. In an intriguing development, the PLAAF apparently sent several Su-27/J-11 aircraft to Turkey in October 2010 to participate in an exercise called “Anatolian Eagle.” This is the first time a NATO country has hosted an exercise that included the PLAAF.11

J-11B. The J-11B is SAC’s response to the PLAAF’s requirement for a true multirole Flanker variant. Based on the Su-27SK airframe, the J-11B features Chinese-manufactured engines and avionics, including indigenous radar, and can be armed with a wide variety of air-to-air and air-to-surface weapons, including the PL-12 MRAAM. Among other improvements, SAC claims that the radar cross-section of the J-11B has been reduced by 75-80 percent from the Su – 27SK by reconfiguring the engine intakes and employing radar-absorbing paint. This degree of signature reduction may strain credulity absent more substantial changes to the airframe, but the assertion alone indicates that the PLAAF understands the advantages afforded by stealth. The J-11B appears to have entered PLAAF service in 2007. A two-seat version, the J-11BS, is under development.

Su-30MKK. The Su-30MKK is yet another derivative of the Flanker family, a two-seat multirole aircraft developed from the Su-27 for the PLAAF. China has reportedly purchased 76 of these Russian-manufactured fighters, which incorporate improved avionics, including a more advanced radar with improved air-to-ground capabilities. The Su-30 can be fitted with a wide array of “smart” and “dumb” weapons and munitions, and it also features a retractable refueling probe. Licensed production of the Su-30 in China was once expected but now appears unlikely, with the two-seat J-11BS potentially occupying what might otherwise have been the Su-30’s “strike fighter” niche in the PLAAF force structure.12

China’s Fifth-Generation Fighter (J-20).13 The first public flight in January 2011 of a stealthy new Chinese fighter, the J-20, came as a surprise to many observers who had agreed with then-Secretary of Defense Robert Gates that China would “have no fifth-generation aircraft by 2020” and only “a handful” by 2025.14 The flight took place while Gates was in China, an irony that may or may not have been intended by the Chinese.

The J-20 appears to be a large airplane, estimated to be about the size of an F-111 by at least two analysts. Its appearance shows that substantial care was taken in the design to shape the jet for low observable (LO) characteristics.15 At this point, all performance specifications are wholly speculative, but the J-20 is thought to have two internal weapons bays and to be capable of “supercruising” flight. In both regards, the aircraft resembles the USAF F-22.

Some accounts report that J-20 prototypes had been flying at a PLAAF test center for several months before the fighter’s official debut in January, and that a total of four airframes are being used in the test program.16

Late in 2009, the PLAAF’s deputy commander, General He Weirong, said that a new fighter would soon “undertake its first flight” and be in service “8 to 10 years” after that.17 This schedule would appear to bring the jet into service around 2016, earlier than previous intelligence assessments had projected.

H-6. The H-6 Badger is the PLAAF’s only true bomber, a twin-engine medium-range aircraft copied from the Soviet Tupolev Tu-16 of the mid – 1950s, with which it shares the same Western reporting name, Badger. The H-6 has been built in a number of versions for both air force and naval use since its first delivery in 1969.18 The newest versions in PLAAF use are the H-6G, which is the carrier platform for China’s first air-launched land attack cruise missile (LACM), the KD-63, and the H-6K, which can carry up to six smaller Tomahawk-like LACMs. The H-6K in particular appears to be a fairly radical reworking of the Badger, with modern turbofan engines apparently replacing the less powerful and less efficient turbojets that powered all previous models, composite materials being used to reduce weight, a modern “glass” cockpit installation, improved avionics, and a thermal-imaging sensor under the nose.

Special Purpose Platforms. The PLAAF has long sought to acquire an airborne early warning and control (AEW&C) platform along the lines of the U. S. E-3 Airborne Warning and Control System (AWACS). A program to buy four A-50I aircraft—a Russian Il-76 Candid airframe equipped with Israeli radar and mission equipment—collapsed in 2000 when Israel succumbed to substantial U. S. pressure and dropped out of the deal. After this disappointment, China moved forward with its own aircraft, also based on the Il-76 platform, but with an indigenously developed mission suite. At least four of these KJ-2000 AWACS aircraft are in active service with the PLAAF, providing it with its first sophisticated airborne battle management assets.19

Another area of interest to the PLAAF is aerial refueling, which is a necessary competence if China intends to extend the reach of its airpower beyond its immediate environs. Today, the PLAAF possesses a fairly rudimentary capability, owning about a dozen H-6U tankers equipped with a “probe and drogue” refueling pod under each wing. Relatively few of China’s combat aircraft can be refueled in the air: some late-model J-8s have probes fitted, and a fixed probe can be installed on the J—10. The PLAAF’s Su-30s have retractable refueling probes, but their system is allegedly not compatible with the H-6U.20

In 2005, China ordered 34 additional Il-76 Candid transports and four Il—78 Midas tankers from Russia, but none have been delivered to date due to a dispute between the Russian export company and the factory responsible for building the aircraft.21 The PLAAF needs not only additional tankers but also more strategic airlifters—if not from Russia, then from its own aviation industry—to achieve any aspirations it might have for possessing a credible power projection capability. In fact, a new large transport aircraft, sometimes called the “Y-20” is reportedly under development; a first flight “around 2012” has been suggested.22

The PLAAF has also developed about a dozen specialized platforms based on the Y-8 four-engine turboprop transport.23 The “Gaoxin” series includes another AEW&C aircraft, a maritime surveillance variant, an airborne command post, and a number of platforms for various electronic warfare functions, such as jamming and signals intelligence (SIGINT).

Unmanned Aerial Systems. Table 8-3 lists unmanned aircraft systems (UAS) deployed or under development in China. They range from a copy of the Vietnam-era U. S. Firebee reconnaissance drone to the Xianglong high-altitude long endurance (HALE) UAS that bears a passing resemblance to the U. S. RQ-4 Global Hawk.

|

Table 8-3. PLAAF Unmanned Aircraft Systems

|

Vehicle Designation

|

Vehicle Type

|

Payload

(kilograms)

|

Mission radius (kilometers)

|

Endurance

(hours)

|

|

Harpy

|

Armed UAS

|

32

|

400-500

|

2

|

|

CH-3

|

Armed UAS

|

63-90

|

1,200

|

12

|

|

Xianglong

|

HALE

|

650

|

7,000

|

unknown

|

|

Yilong

|

MALE

|

200

|

unknown

|

20

|

|

BZK-005

|

MALE

|

150

|

unknown

|

40

|

|

ASN-206

|

MAME

|

50

|

unknown

|

4-8

|

|

ASN-209

|

MAME

|

50

|

100

|

10

|

|

LT series

|

MAV

|

unknown

|

10-20

|

0.3-0.6

|

|

ASN-104

|

RPA

|

30

|

60

|

2

|

|

Chang Hong*

|

RPA

|

65

|

1,250

|

3

|

|

ASN-105B

|

RPA

|

40

|

150

|

7

|

|

AW series

|

Tactical

|

unknown

|

5

|

1-1.5

|

|

W-30

|

Tactical

|

5

|

10

|

1-2

|

|

Tianyi

|

Tactical

|

20

|

100

|

3

|

|

W-50, PW-1

|

Tactical

|

20

|

100

|

4-6

|

|

PW-2

|

Tactical

|

30

|

200

|

6-7

|

|

U8E

|

VTOL

|

40

|

75

|

4

|

|

Soar Bird

|

VTOL

|

30

|

150

|

4

|

Source: Data from Jane’s (2010) and SinoDefence{nid).

HALE: high altitude, long endurance MALE: medium altitude, long endurance MAME: medium altitude, medium endurance

MAV: micro air vehicle RPA: remotely piloted aircraft VTOL: vertical takeoff and landing

*The Chang Hong may also be referred to as the "WuZhen-5."

|

In the past decade, China has displayed a dizzying array of various UAS models at air and trade shows; many if not most seem never to have gone into production. A look at the table suggests that China is experimenting with many classes of UAS, mostly for surveillance and reconnaissance. Of particular interest is the Harpy, an Israeli-made antiradiation drone. It flies to a target area and loiters until an appropriate target begins to emit, at which point it dives into the target and detonates. Harpy is an interesting hybrid of UAS and cruise missile, somewhat akin to the cancelled American AGM-139A Tacit Rainbow program of the late 1980s.

Air-to-air missiles: Table 8-4 lists air-to-air missiles (AAMs) in service with the PLAAF. As can be seen, for many years the PLAAF was equipped with obsolete AAMs. Through to the mid-1980s, the most common missile in its inventory was the PL-2, a Chinese copy of the Soviet AA-2 Atoll AAM, itself a copy of the first-generation U. S. AIM-9B Sidewinder. But, in the early 1990s, this began to change. Along with Russian Su-27s came modern Russian missiles: the R-27/AA-10 Alamo radar-guided medium-range air-to – air missile (MRAAM) and the R-73/AA-11, short-range AAM (SRAAM), which at the time was probably the best visual range “dogfight” missile in the world. As well, China developed two indigenous infrared homing SRAAMs, the PL-8 and PL-9. The PLAAF fielded its first indigenous MRAAM, the PL-11 semiactive radar homing missile, developed from the Italian Aspide (which Beijing had purchased in small numbers) around the turn of the century. Along with its Su-30s, China procured a number of R-77/AA-12 “fire and forget” MRAAMs from Russia. Shortly thereafter the PLAAF also began fielding the PL-12, an indigenous active-homing MRAAM compatible with most of its modern fighters.24

|

Table 8-4. Current PLAAF Air-to-Air Missiles

|

Designation

|

Year introduced

|

Type

|

Range

(kilometers)

|

Notes

|

|

PL-2

|

~1970

|

IRH

|

3

|

Copy of AIM—9B

|

|

PL-5

|

~1987

|

IRH

|

16

|

Similar to AIM—9G

|

|

PL-8

|

~1990

|

IRH

|

15

|

Based on Python 3

|

|

PL-9

|

early-1990s

|

IRH

|

15-22

|

|

|

PL-11

|

~2001

|

SARH

|

25

|

Based on AIM-7, Aspide

|

|

R—27/AA—10

|

mid-1990s

|

SARH/IR

|

60-80

|

On Flankers

|

|

R—73/AA—11

|

mid-1990s

|

IR

|

30

|

On Flankers

|

|

R—77/AA—12

|

~2003

|

ARH

|

50-80

|

On Flankers

|

|

PL—12/SD—10

|

~2004

|

ARH

|

70

|

|

|

Source: JatneS (2010) ARH: active radar homing

|

IRH: infrared homing SARH:

|

semiactive radar homing

|

|

|

|

Both the AA-11 and the PL-9 are reportedly compatible with helmet – mounted sights, which allow the missile to be locked onto an air target when the pilot looks at it. When combined with the missile’s “off boresight” capability—it can be fired at targets to one side or another of the launching aircraft up to some specified limit—the sighting system streamlines the engagement dynamics of close-in aerial combat.

Looking ahead, it has been reported that China is working on at least three new AAM designs: an extended-range ramjet powered version of the PL-12, a short-range active radar homing missile, and the PL-ASR, an IR missile employing thrust vector controls which would provide greater agility to the weapon.25

Air-to-surface missiles: Table 8-5 lists air-to-surface missiles (ASM) reportedly fielded by the PLAAF. They range from the Hellfire-class AR-1 to the HN-1, a Tomahawk-like long-range cruise missile (LRCM). In addition to these missiles, China is also beginning to deploy laser- and satellite-guided bombs, although it is not clear whether they are yet available in operationally significant quantities.26

|

Table 8-5. Current PLAAF Air-to-Surface Missiles

|

Designation

|

Type

|

Guidance

|

Range

(kilometers)

|

Warhead

(kilograms)

|

|

AR-1

|

ATGM

|

Semiactive laser

|

8

|

10 AP

|

|

Kh—31/AS—17/YJ—91

|

ARM

|

INS/passive radar

|

15—110

|

87kg HE

|

|

KD-88

|

ASM

|

INS/EO/RF

|

”100+"

|

(unknown)

|

|

KD—63*

|

LACM

|

INS/EO

|

200

|

512 HE

|

|

HN—1

|

LACM

|

INS/GPS/TERCOM

|

600

|

400 HE/SM

|

Source: Jane’s{2010).

AP: armor-piercing ARM: antiradiation missile ATGM: antitank guided missile

EO: electro-optical GPS: global positioning system HE: high explosive

INS: inertial navigation system LACM: land attack cruise missile RF: radio frequency

SM: submunition TERCOM: terrain comparison and matching

*The KD—63 is also referred to as the YJ-63.

|

Surface-to-air missiles. The PLAAF operates China’s long-range strategic surface-to-air missiles (SAMs); as table 8-6 shows, these are a mix of indigenous and Russian designs. While the HQ-2 is obsolete, the HQ-9, HQ-12, and SA-300 variants are all very capable systems. Of particular interest is the HQ-12, which appears to have been designed expressly to attack AWACS – type aircraft and jamming platforms; it is unique in being a surface-to-air antiradiation missile (ARM). The table includes the new S-400 SAM system that has entered service in Russia. No exports of this very long-range SAM—the intended successor to the S-300 series—are as yet reported, but China, which is said to have paid for a substantial portion of the system’s development, is likely to be an early customer for it.

|

Table 8-6. Current PLAAF Surface-to-Air Missiles

|

Designation

|

Guidance

|

Range

(kilometers)

|

Notes

|

|

HQ-2

|

Command

|

35

|

Similar to Russian S-75/SA-2

|

|

HQ-7

|

Command

|

12

|

Similar to French Crotale

|

|

HQ-9

|

Track via missile

|

200

|

Merges S-300 / Patriot technology

|

|

HQ-12/FT-2000

|

Inertial navigation system / passive radar

|

100-120

|

Targets airborne warning and control, electronic warfare aircraft

|

|

S-300PMU

|

Radar homing

|

90

|

5V55RUD missile

|

|

S-300PMU1

|

Track via missile

|

150

|

48N6E missile

|

|

S-300PMU2

|

Track via missile

|

200

|

48N6E2 missiles

|

|

S-400

|

Inertial navigation system / command / radar

|

up to 400

|

9M96, 40N6 missiles

|

Source: Jane’s (2010)

|

Measuring Up: The PLAAF’s Equipment versus the United States

Consider the circumstances had U. S. and Chinese fighter pilots encountered one another in the skies near Taiwan in 1995. The American would have been flying a fourth-generation F-15, F-16, or F/A-18, armed with AIM-120 advanced medium-range air-to-air missiles (AMRAAMs) and AIM-9L/M short-range air-to-air missiles (SRAAMs). The U. S. pilot would almost certainly have been supported by a controller in an E-3 AWACS, and would have found a KC-135 tanker orbiting nearby in the event that fuel became an issue.

For his part, the PLAAF pilot would most likely have flown a MiG-21 variant without any medium-range missiles, being armed instead with only obsolescent PL-2 or PL-5 short-range IR weapons. While a ground controller back on the mainland would have helped manage and inform the PLAAF pilot’s sortie, that controller’s picture of the relevant airspace would have been substantially inferior to the one being monitored inside the AWACS as it cruised high above. And there would have been no tankers available to provide additional fuel should that have been necessary or desirable. In short, the Chinese airman would have been flying an obsolete aircraft carrying antiquated missiles, have modest situational awareness, and, as is discussed elsewhere, would himself have been the product of inferior training and preparation compared to the U. S. pilot. Thus, he would have been overmatched and outgunned.27

Now fast-forward 15 years. While the U. S. pilot would most likely be in essentially the same plane with essentially the same weapons and essentially the same support, the picture on the PLAAF side would be very different. Consider the following changes:

The PLAAF Now Has Platforms Comparable to U. S. Platforms

The PLAAF’s Su-27/J-11s are often compared to the U. S. F-15, the J—10 to the F-16, and the Su-30 to the F-15E. As table 8-7 shows, these comparisons are not far-fetched; though hardly identical, the two sides’ jets clearly seem to fill parallel slots in their respective force structures.

|

Table 8-7. USAF vs. PLAAF Fourth-Generation Fighters

|

Type

|

Initial operational capability

|

MTOW

(kilograms)

|

Range

(kilometers)

|

Armament

|

|

F—15C

|

1979

|

30,845

|

>2,500

|

Up to 8 air-to-air missiles

|

|

Su—27/J—11

|

~1997

|

33,500

|

4,900

|

Up to10 air-to-air missiles

|

|

F—15E

|

1989

|

35,741

|

2,540

|

11,113 kilograms

|

|

Su-30

|

2001

|

34,500

|

3,000

|

8,000 kilograms

|

|

F-16C

|

1984

|

21,772

|

1,550

|

4,200 kilograms

|

|

J-10

|

~2006

|

18,500

|

~1,100

|

4,500 kilograms

|

Source: Jane’s (2010)

|

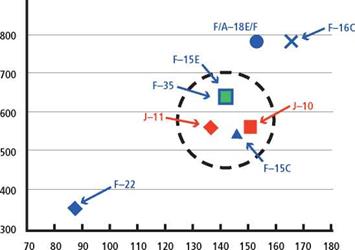

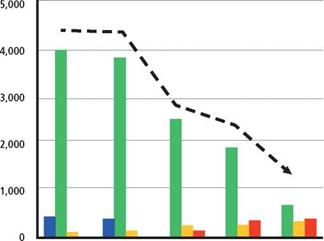

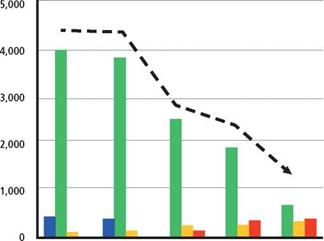

The similarities between each side’s “fourth-gen” fighters go beyond static comparisons of size and payload. Plotted in figure 8-2 are two factors for each of eight aircraft: weight-to-thrust and wing loading. The first shows the relationship between an aircraft’s weight and the power of its engines, and the second the relationship between its weight and the surface area of its wings.28 These factors help determine a fighter’s maneuverability in both the horizontal (banks and turns) and vertical (climb and dive) dimensions. Lower is better for each factor, so the farther down and to the left an aircraft lies, the better.

Unsurprisingly, the USAF F-22—seen in the figure’s lower left corner— is superior on both counts; in the upper right are the F-16C and the F/A— 18E/F, which trail the pack in these two regards. Clustered in the middle are five aircraft, the F-15C, F-15E, F-35, J—10, and J—11, which are in more or less the same neighborhood on these two important characteristics. While weight – to-thrust ratio and wing loading vary over the course of a mission as fuel is burned and ordnance expended, these platforms themselves start out broadly similar in these important factors.

|

Figure 8-2. Weight-to-Thrust Ratio and Wing Loading, PLAAF vs. U. S. Fighters

W/T (kg/kn)

Source: Jane’s(2010)

|

The J-10B and Flanker variants are equipped with passive IRSTs. These sensors can permit a pilot—without emitting a radar signal— to detect another aircraft by “seeing” the heat from its engines, the friction produced as it moves through the air, or the heat signature from the launch of a powered missile. Sukhoi claims that the OLS-35—developed for its Su-35 advanced Flanker— has a front hemisphere detection range of 50 kilometers (30+ miles), and as much as 90 kilometers (55+ miles) in the rear hemisphere, where it is “looking” at the hot exhaust of a target aircraft.29 While the OLS-27 and OLS-30 that equip China’s Su-27/J-11s and Su-30s, respectively, are less capable, it is worth noting that no current generation U. S. fighter has an IRST at all, not even the F-22.30 The forthcoming F-35 (now in advanced flight testing) will mount an IRST, and programs are underway to retrofit both the F-15C and F/A-18E/F.31

1st Generation

1st Generation