(General Hobbs to General Rawlinson)

Captain Bean was at a disadvantage at the start of his investigation. The science of ballistics was in its infancy and he had not seen any of the three medical reports.

He had only the witnesses to go by, and there were hundreds of them.

To begin with, of the one thousand plus soldiers in the area bounded by Vaux-sur – Sonime, Corbie and Bonnay, only about ten had seen a second Camel attack the Triplane, and they were mainly from other units which he did not consult. This left him with Gunner George Ridgway, Lieutenant Quinlan and Lieutenant Wood, and if they were correct, the Triplane had not been hit. Basically, he found a thousand men who said that a second Camel had not been involved in the fray, and three who claimed to have seen it.

Many of the thousand had seen other aeroplanes in the distance, but said that they were too far away to have been involved. He did not have the benefit of Sergeant Derbyshires description of Browns attack and his observation that the Triplane seemed to run into a brick wall in its flight. Gunner Twycrosss evidence on the time of von

Richthofens death remained unrevealed to the world until 1996.

Private Emery and Private Jeffrey were keeping low profiles. The battalion officers were trying to learn who had souvenired the Barons binoculars and luger pistol by means of surprise kit inspections.

THE OFFICIAL REPORT TO THE COMMANDER-IN-CHIEF

Official Report on the Death of the Red Baron.

2.

2.

and circled above the spot until driven off by the A. A. guns.

An Infantry guard wae posted over the body and the plane, but they were relieved of their duty shortly after by the German artillery, who placed a ring of shells, bursting with Instantaneous fuzes, around the plane.

The Lewis gunners who brought down the plane were:

No. 598 Gunner W. J. Evans and No 3801 Gunner R Buie, of the 53rd Battery, 14th Australian Field Artillery Brigade, 5th Australian Divisional Artillery.

and they did not wish to draw attention to themselves. The missing information held the key to the sequence of the main events which perplexed Captain Bean. As things stood. Bean could not deduce ‘x’ by relating it to ‘y’ and V; the latter two were also uncertain in time, place or both.

After much interviewing, discussion and thought, Captain Bean gave his decision. General Hobbs’s HQ staff set down the only document which can be described as the Official Report and which is held at the Australian War Memorial in Canberra. It contains a few typing errors.

The Official Report which is undated, was sent to General Sir Henry Rawlinson around the middle of May. It was classified Secret which doubtless avoided a head-on collision with RAF HQ it the contents became widely known. The general lack of knowledge until the 1960s concerning this report

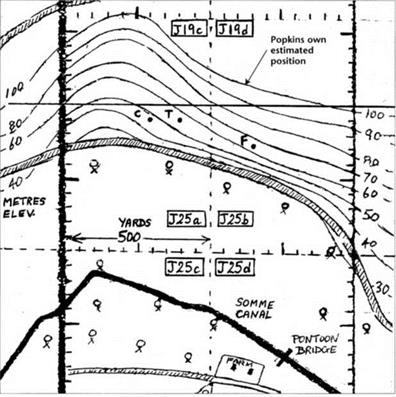

This Official Report describes von Richthofens wounds incorrectly, which is proof that the contents of the medical reports were restricted to very senior officers. It seems amazing that having asked Bean to investigate the incident, he at least was not given access to them. One might even assume that Hobbs did not see them or surely he would have felt compelled to have the report altered at least to correct the wounds. The report also repeats the incorrect map reference positions given originally for Gunners Buie and Evans and the Triplane’s forced landing site. The correct ones are: Buie – I.24.b.65.36; Evans — I.24.b.74.43, and theTriplane – J.19.b.40.30.

General Hobbs sent a telegram of congratulations to the 53rd Battery. General Salmond countered by sending a telegram of congratulations to 209 Squadron. It can be said that RAF HQ and the Fourth Army HQ agreed to differ.

This, however, was not the end of the matter for Captain С E W Bean continually received statements from people whom he had not interviewed during April 1918 (the German offensive caused much disruption) and he reexamined the whole business after the war.

CHAPTER NINETEEN

Captain Bean Changes his Mind

Between 1930 and 1934, when the Official Histories of the Great War were being written, С E W Bean in Australia and H A Jones in England corresponded on a frequent basis. Extracts from the reports on the first two medical examinations were available and Bean may even have seen a complete copy of the third one.

Bean’s support for Gunners Buie and Evans, although expounded by hundred of witnesses, began to wane. The Baron was definitely alive and flying his Triplane after they had ceased firing. The sudden climb in which the Triplane almost turned over was finally explained; it was the convulsive reflex action attendant upon a painful wound. Private Emery stated that this occurred after Buie and Evans had ceased firing, and certainly the position of the Triplane on the way to Sainte Colette would not have allowed Buie or Evans to fire at it frontally, or even semi-frontally. It had already passed overhead, turned to the right and was flying away from them at the time. Emery actually saw and heard more than that, but whether he told Bean would be to speculate. Vincent Emery’s complete observations only became public knowledge in 1975, telling them to Australian Historian Geoffrey H Hine, and therefore belong in a later Chapter of this work.

In a letter dated 13 November 1959, to Colonel G W L Nicholson, Director of the Historical Section of the Canadian Army, Bean wrote: [an authors’ note at the end explains Bean’s numbered references to Nicholson’s questions.]

Dear Colonel Nicholson,

Your letter of the 9th October caught me on one foot, as it were – although the trouble is at the other end; I have been overstraining my powers on the eve of my 80th birthday and have been told that the best way to meet this situation is to cut out all writing for a month or two. For that reason, on visiting Canberra for Remembrance Day I took your letter with me and asked the officer in charge of the records at the War Memorial and his chief assistant (Mr Bruce Harding and Miss Vera Blackburn) if they would do their best to find the most important references for which you ask, and have them copied for you. I think the best help I can give is perhaps to tell you, without research, of

the way on which I became specially interested in the death of Richthofen.

I think it was on the day after Richthofen’s death that I. then the chief Australian official war correspondent in France and the probable future historian of the Australian part in the war. received a request from General Hobbs, then commanding our 5th Division on the Somme, to go up and investigate the shooting down of Richthofen which had been reported in the press and communiques. I had heard that he had been shot down by an airman of the RAF but General Hobbs said that his men were very incensed at this report as they claimed he had been shot down by the Australians over whom he was flying. My immediate reaction was the thought: ‘Why dispute the claim of an airman whose task and risk were immensely greater than that of men shooting from the ground?’ However, if I remember rightly, the two Lewis gunners of the 53rd Battery who claimed to have shot Richthofen down were at once sent to me: and after closely questioning them, I had no doubt that their bullets struck Richthofen’s plane as it topped the spur south-east of Bonnay and flew low towards them, and that he gave up the chase at that point, and almost immediately crashed. As they, and others, had seen fragments fly from the plane, it seemed probable that they had killed him. When news spread that a British airman had claimed to have done so. it was assumed by those who watched (or like myself had been told of) the fight that the claimant was the man whom Richthofen had been pursuing. All the accounts that came from the ground over which the pursuit took place spoke of two planes only, that of the pursuer grimly firing bursts at the pursued, and that of the pursued, veering from left to right and back, and up and down, in what seemed to be a desperate effort to evade them.

From Vaux-sur-Somme along the Somme Valley (down which the chase had gone very low and thence over the spur between the Somme and the Ancre) it had been watched by hundreds of troops who, drawn by the rattle of machine guns and the whir of the planes ran out of their billets or bivouacs. Among those who did so were several friends of mine; Lieut-Col J L Whitham, a very close friend and a grand soldier ’preux chevalier’ as I always felt. Major Blair Wark VC. Brig. Gen. J В

Cannan and others; the one thing that impressed me was that none of them, who described the chase vividly, said anything about a third plane.

It was not until I was writing Vol. V of the Official History in 1934 that I came upon two items of information – I cannot from memory say where – that two Australians had. on the day of Richthofen’s death, been watching separately the general dog fight in the air somewhere east of Vaux-sur-Somme and had seen THREE planes, one German and two British, dive out of it into the Somme Valley. Each observer said that one of the British planes turned out of this chase, but the other, with the German on his tail, kept on.

This was the first I had heard of any observer in our area having seen a third plane in the chase, and from then onward my main enquiry into this Incident was concentrated on the question whether anyone had seen a third. Neither my letters to those whom I knew to have seen the chase, nor interrogation of them when I met them, brought any other answer but that there were only two in the chase along the valley and up the ridge, almost exactly a mile. Extracts from all the important statements are given in the appendix Vol. V.

A medical officer. General Barber, who had seen Richthofen’s wounds, told me that it was out of the question that, with a wound in the neighbourhood of the heart such as the one which killed Richthofen, he could have made the intense attack, for a mile or over from Vaux onwards, that so impressed those who watched it.

That, to my mind, completely disposed of Brown’s claim. But the question of who shot him remained open; though many machine and Lewis guns besides those of the 53rd Battery had shot at Richthofen. I was disposed to think that those Lewis gunners had probably done so [shot von Richthofen]; there was no doubt that they (or one of them) hit his plane at close quarters. It was not till I examined the claim of Popkin that I was strongly impressed with HIS claim. Whether I examined him personally or wrote to him I cannot remember though a pencilled note in my papers in Canberra may have been made at an interview. But Lt. Wiltshire (p.696) said that Richthofen had not crashed immediately he was stopped, but turned and began to climb back towards his own lines. It was at this stage that Sgt. Popkin from the Somme valley below, fired at him for the second time with his Vickers machine gun, and he claims to have ‘observed at once that his fire took effect’ (as mentioned in his report).

As scores of rifle shots as well as those from other Lewis and Vickers guns

were aimed at the red plane it is possible that the fatal shot may have been from one of them: I could only conclude with certainty. I think, that Richthofen was shot from the ground; and that I judged that Popkin’s claim was the best of those which I heard or read. As to your other questions:

1. I cannot recall having heard that Brown denied having written the article in the Chicago Tribune. I wrote to him at least twice – first for confirmation of his name, initials, home town. etc. To which he replied: later I wrote again asking about the difficulties we had found in his narrative; to this I received no reply. I cannot offhand say whether the Tribune and Liberty articles are the same; I will ask Mr. Harding whether we have both articles.

2. As to the statements in Italiaander’s book (1)(which I have not seen), and also of Wiltshire, that at the start of the affair Richthofen was chasing two British planes. I cannot judge, except that it seems improbable. All that I know, with certainty, is that from the west of Vaux onwards there were only two planes in the chase, Richthofen’s and May’s. At the beginning, during the dive there were (on the evidence we have) three. The difference between Ridgway’s account and Wiltshire’s may, as you suggest have been due to difference between the positions and angles of vision of the observers, or to mistaken memories, though my experience is that, of such events, the memories of most eyewitnesses do not fade for twenty years unless they are blurred by being told and re-told, as often they naturally are.

3. I heard that an officer of the 3rd Squadron AFC had put 1n a claim but it was not seriously regarded by those to whom I spoke.

4. Brown certainly did not make a second attempt to get Richthofen unless he had already made one attack before our story began: and in the narrative attributed to him in the Chicago Tribune, he says nothing of it. It certainly did not happen after Richthofen first dived on May.

5. As I understand Popkin’s action, he fired at Richthofen first from Richthofen’s left when the two planes passed at the end of the chase; but when the German turned and began to make for his own area. Popkin was shooting from Richthofen’s right; otherwise Richthofen must have swung widely round to the south and the second passing would have been in the rear of Popkin. of which I have never heard any evidence.

6. Mr. Harding tells me that no award was made to an Australian for shooting down Richthofen.

(1) Manfred Freiherr von Richthofen by Rolf von Italiaander,

published in Berlin in 1938.

7. There were visitors from the RAF. I will ask Mr. Harding to see if he can check on those from the 204th Squadron.

I am most sorry that I could not go fully into the documents myself; some urgent work in connection with my retirement from the chairmanship of the Australian War Memorial Board and also from that of the Commonwealth Archives Committee, and several consequent functions, brought me almost to a breakdown and I was told that a temporary rest was necessary – though the extreme interest of the work is a constant temptation to disregard the advice. Please excuse the roughness of this typing – I cannot inflict my handwriting on you. With every good wish for your work, both generally and in this matter, of which I was very glad to learn.

Yours sincerely, С E W Bean.

Authors’ Comments:

Colonel Nicholson had queried Dr Bean MA, D. Lit., concerning some strange assertions made in Л/у Fight with Richthofen (of which three slightly different versions exist) and in a book Von Richthofen and the Flying Circus (Harleyford. 1958). He was also curious about a few other publications. Background and/or information on his queries follows below. It is given in the same order.

1. The question of Browns authorship of My Fight with Richthofen is covered in Appendix E.

2. The view that von Richthofen was at one time

chasing two British planes could be due to the deceptive nature of three-dimensional slant views. There were several other aircraft around in the background at the time, both British and German, and one of those could have been mistaken as being part of the affair. Certainly no expert Fokker Triplane fighter pilot in his right mind would try to chase two faster Sopwith Camels; whilst he was dealing with one Camel, the other would slip round behind him and

3. The officer of 3 Squadron AFC’ who filed a claim was Lieutenant Barrow. His claim was withdrawn; the time of his encounter with Jasta 11 was too early.

4. In the book Von Richthofen and the Flying Circus. its authors and editor follow the belief that Brown attacked von Richthofen somewhere between Sailly-le-Sec and Vaux-sur-Somme. Since nobody in Vaux or the windmill FOP saw the attack happen, they believe it must have occurred just after

Sailly-le-Sec. This would have required a gravely wounded von Richthofen to chase May in a most expert manner down the river, turning by the church tower at Vaux, along the ridge front, up the bluff, over the battery and then TWO MINUTES after Browns attack to die from his wound and crash. That being obviously impossible, the authors, wanting to show that Brown could have killed the Baron, suggested there was a case for a second attack by Brown just about the time that the Triplane flew over the 53rd Battery on its way to the field at Sainte Colette. Thus, by a reverse process, they deduced the place of Brown’s attack from the time it would take von Richthofen to die from such a wound as he had suffered. The tail is wagging the dog again.

Unfortunately not one of the approximately 1,000 spectators, from private to general officer, saw Brown make such an attack which would have been in their unobstructed view, close by and at low altitude. The contorted proof of the imaginary event is that Brown was indeed in the area at the time which, in the view of the authors of the Harleyford book, made a second attack possible. After recovering from his dive and south-west turn, he had turned right in the vicinity of Corbie, then headed north towards Bonnay to check that May was safe before heading back to Bertangles.

The authors of the Harleyford book would have been extremely glad to have John Column’s testimony from Sergeant Gavin Darbyshire, Private Jack O’Rourke and E E Trinder, for, once Brown’s attack has been positioned correctly, von Richthofens remaining flight path becomes short enough for him to have succumbed to such a wound within the bounds of possibility.

The positive aspect of the suggested second attack is that it clearly demonstrates that the Harleyford book authors were not happy [present authors’ note: and with good reason] with the time factor relative to the events.

5. An un-named publication discounted Sergeant Popkin’s affirmations that he fired at the left of von Richthofen’s Triplane and that his second burst was at the right. It claimed both times he fired at the right. Apparently the good sergeant knew not what he did.

6. It was only in the imagination of whoever edited My Fight until Richthofen that two Australian soldiers received medals.

7. There is a story that on 20 April a pilot (named Lieutenant J A E R Daley) from 24 Squadron RAF (SE5s) performed aerobatics over the two gun batteries. A complaint had been made by the Officer Commanding and the pilot had been told

to go to the Battery HQ and apologise the next morning. He was there when exciting things were happening and may have also been the source of the legend of the mysterious RAF pilot who ‘landed nearby’.

С E W Bean’s later discoveries indicated Sergeant Cedric Basset Popkin and eliminated his earlier nominees. Gunners Buie and Evans. In the section entitled Conclusions in Appendix 4 to The All-‘ in Tronic (page 7(H)). Bean wrote:

It is also clear that Sergeant Popkin’s gun when first fired, and those of the 53rd Battery, cannot have sent the fatal shot – since it came almost directly from the right and from below the aviator – although they may well have caused him to turn, but that scores of other men were firing and. when Richthofen banked and turned back. Sergeant Popkin (who now opened fire again) was in a position to fire such a shot as killed Richthofen. Private R F Watson, who helped Popkin’s gun, wrote, on the day of the event, that their previous burst did ‘some damage’, but that the second burst ‘was fatal’.

This was when Popkin himself, according to his statement made at the time, ‘observed at once that my fire took effect’.

It is just conceivable that Captain Brown, although above and behind him [1], could have inflicted such a wound in the region of the heart, he should have continued for a mile [2] in his intensely purposeful flight, closely following the movements of the fugitive airman and endeavouring to shoot him. Certainly no one who watched from the ground the last minute [3] of that exciting chase with only two ’planes in the picture will ever believe that Richthofen was killed by a shot from a third aeroplane which no one from Vaux onwards observed.[4]

Authors’ notes:

Ш Brown’s oft-repeated statements that he was above, behind and to the left, had reached Bean in the misleading abbreviated form which omitted the key word left.

2) The horseshoe path taken by the Baron was indeed about one mile, but the straight line distance from where Brown attacked and the Baron fell is closer to half a mile.

(3) The last minute of the Baron’s life is better comprehended if divided into about 30 seconds flying, 15 seconds making an emergency descent and landing, and 15 seconds dying.

[4] Obviously Bean knew nothing of Sergeant Darbyshires pontoon bridge repair crew which belonged to a British Engineering unit, and apparently he did not absolutely trust the word of Gunner Ridgway and Lieutenant Wood. There are reasons for this.

Ridgway had been handing around ‘copies’ of the nameplate from Richthofen’s Fokker Dr. l 425/17, and some people had thought that they had received the original one. Unfortunately there were three spelling mistakes in the German, and excepting Fokker, the same words in Dutch are totally different. In addition, the layout resembled a nameplate from a Fokker E. III (a monoplane of 1915 vintage), nothing like that used on a Dr. l.

Lieutenant Wood had written that his platoon was about four miles from the battalion station in Corbie, which was why they had their own field kitchen. The army map, 1917 or 1918, shows the distance to be about 1 to ‘/. miles only. On this basis. Wood’s testimony has been discredited by many, it being obvious that if he was four miles from Corbie, he was nowhere near Sainte Colette. To verify this, the authors drove along the route which would have been followed to take supplies from Battalion HQ to the platoon near Corbie in the daytime. If a short cut via a cart-track were taken, the distance was 3.8 miles. The all-weather route was 4.2 miles.

Additional support for Sergeant Popkin was yet to surface. Private Bodington of the 10th Australian Field Ambulance revealed many years later that he had been ordered to deliver a dispatch, and was walking along the top of the Ridge with it in his hand when he saw the Triplane coming towards him. He heard a machine gun to his left open fire and saw the Triplane make a sudden steep climb and then nose down. It came to earth near a brick kiln 500 yards away from him. Bodington added that it was the only aeroplane around and that the machine gun, from 24th Machine Gun Company, was the only one he heard firing at it.

С E W Bean, as the Official Australian Historian, may not have researched other units in the area so much as he should have, but his errors of omission were in no way so grave as H A Jones’s errors of commission. In letters between Jones and Bean, a strong impression surfaces that Jones (the Official British Historian) appeared to believe that My Tight with Richthofen was a true account written by Captain Brown and that he was following its basic line. He discounted all eye-witnesses to the contrary, including statements definitely made by Brown, and produced a seriously flawed work which has been cited by some as proof that the content of My Tight with Richthofen is indeed correct, if somewhat exaggerated. Researching in circles is an apt label for the process.

CHAPTER TWENTY

These positions, if true, would have had little defensive value.

These positions, if true, would have had little defensive value. survived the war, and the coincidence is not accidental, he kept a sharp look-out at all times and in all directions. Down to his right nearVaux, he saw three aeroplanes; a Camel, followed by a Triplane — both heading west; then a second Camel, higher up, diving at about a 45° angle to intercept the Triplane. Taking a good look round every few seconds and turning his own Camel as required to be sure that no enemy was sneaking up on him, he watched the show from a front row seat in the Gallery.

survived the war, and the coincidence is not accidental, he kept a sharp look-out at all times and in all directions. Down to his right nearVaux, he saw three aeroplanes; a Camel, followed by a Triplane — both heading west; then a second Camel, higher up, diving at about a 45° angle to intercept the Triplane. Taking a good look round every few seconds and turning his own Camel as required to be sure that no enemy was sneaking up on him, he watched the show from a front row seat in the Gallery.

2.

2.