The First Medical Examination

(The Midnight Preview)

On the evening of 21 April, Major Blake, the CO of 3 Squadron AFC, received word from 22 Wing HQ that Lieutenant-Colonel Cairnes (1) was sending the new Wing MO, Captain Norman Clotworthy Graham RAMC, to his aerodrome to examine von Richthofen’s body. One must assume that Cairnes was in hopes that at least the dispute between the two squadrons under his command could be resolved before the ‘top brass’ (the Fourth Army Consulting Surgeon and Consulting Physician) arrived on the morrow. Judging from the after duty hours activity which then took place, the 3 AFC medical orderlies received instructions to clean the body up a bit and to lay it out neatly.

During this activity, the senior orderly, Corporal Edward McCarty, discovered a spent bullet inside the clothing at the front of the body. Actually it fell out unexpectedly, so he could not say precisely where it had been lying. Others saw him pick it up and heard him comment on it; this eliminates the discovery being a later‘tall story’ on McCarty’s part. The body had been moved around quite a bit since the Baron died, so exactly where the bullet came to rest is unknown. The knowledge as to between which layers of clothing it was resting was also lost when it fell out of its own accord. McCarty’s belief was that upon exiting the body, further travel of the bullet had been arrested by the bulk of a leather wallet which he found in the breast pocket of an inner garment. The details are somewhat garbled and in the light of the knowledge that von Richthofen pulled his flying suit on over his pyjamas, it is more probable that the wallet was in an inside pocket of the suit. This would also explain the fact that those who had earlier searched the body for valuables and had found a large sum of French money, had missed the wallet. The bullet was not pristine; it bore a sharp indentation indicative that it had struck something hard at some stage.

During the 1960s the late Pasquale Carisella succeeded in finding the ‘owner’ of the wallet and obtained four excellent photographs of it; one of each of the shiny leather surfaces: two exterior and two interior views. Author Bennett has seen these photos and can affirm that none of the four faces bears any mark or dent whatsoever. It therefore would appear that the final energy of the bullet was consumed in breaking through the skin and possibly the pyjamas, and that it came to rest against the inside of the heavy fur-lined flying suit.

There were two other mentions of a bullet on the body, curiously enough both by members of Sergeant Popkin’s gun team, Privates Weston and Marshall. Weston said that it was on the left side partially embedded in a book. It may have been hearsay for, in extensive correspondence with historian Frank McGuire, he never mentioned it. Sergeant Popkin told С E W Bean, the Australian Official Historian for the 1914-18 war, that Marshall had taken a bullet from the body. Marshall was killed later on in the war; however, it is strange that no one else has mentioned such an interesting‘find’on his part. The most probable explanation is that either Marshall or Weston saw the bullet and decided to leave it well alone. Corporal McCarty found it later on that evening.

At about 2330 hours, Major Blake and his Recording Officer, Captain E G Knox, arrived at the tent-hangar where the body had been laid out. They were accompanied by Captain Graham and his predecessor, Lieutenant Downs, who was to leave France four days later to take up a posting in England. The captain had arrived just the previous day, Saturday the 20th, and had immediately assumed his new function.

The two MOs, without doubt, had heard from Lieutenant-Colonel Cairnes about his visit with Roy Brown to the 53rd Battery, and it is logical to assume that Major Blake had already spoken to them about the red Triplane which Lieutenants Barrow and Banks had forced out of the fight over Le Hamel. The task before the two doctors might be a fairly simple one; namely a dispute between three bursts of machine-gun fire; all from 50 to 350 yards range, but from completely different angles towards the Fokker.

(1) Lt-Col Cairnes arrived at 22 Wing from Home Establishment on 17 April and would take full command from Lt-Col FV Holt on the 25th.

Whilst they made their examination, about 20 officers from 3 AFC watched from a respectful distance. One of them was Lieutenant Banks, the RES observer who had a stake in the game.

The first unexpected discovery was that tar from having been the victim of a burst of machine-gun fire, only one bullet had struck the body. What had been taken to be a multiple bullet entry wound was actually the exit wound of a – ingle bullet. The other‘bullet wounds’ all turned ‘Ut to be impact injuries, sustained in the cockpit during the crash landing.

According to witness testimony received by Dale Titler. Lieutenant Downs noticed something ^bout the body which suggested to him that the bullet had not followed a straight path from the entry point to the exit point. The nature of this mething’ has, unfortunately, never been disclosed.

In an attempt to discover what that ‘«•omething’ might have been, the present authors. onsulted three gunshot wound specialists; one in Canada, one in England and one in Australia. They.11 indicated that when dealing with a Spitzer-type bullet, the entrance wound will often give an indication of the angle at which the bullet struck me victim. If it strikes the skin perpendicularly, its harp point, followed by an aerodynamically – – haped increasing diameter, will make a neat round hole and the abrasions around the inner edge of the hole will be equally distributed. As the angle of impact moves away from the perpendicular, so will •he hole become progressively unequal. The exception will be if the bullet has struck something else first and has either become deformed or has begun to tumble.

Dale Titler’s witness also revealed that Lieutenant Downs had tactfully suggested to Captain Graham that perhaps the bullet had dog – legged on its way through the body (possibly via touching the spine). Whether he drew Grahams attention to the entry wound is unknown. The witness continued that Graham, after looking at the size of the exit wound which was much larger than the entrance one, was of the opinion that it was still not large enough to have been caused by a bullet which had deflected off the spine. This was not exactly true, for the size of an exit wound in the trunk or the abdomen made bv a Spitzer-type rifle bullet depends mainly on a combination of its spinning rpm at the time of impact and how far it has travelled through the body tissue.

Two of the three claimants said that they had tired from 50 to 100 yards range. The third one had opened fire at 350 yards range (noted as long range by his standards) and had ceased fire at about 50 yards range. The wound characteristics, being identical between 400 and 800 yards, would not reveal the range at which the shot was fired. The distance travelled through body tissue rapidly reduces the rpm of the spin |from the rifling] which permits the bullet to begin to tumble (change from point-first to base-first travel). The conversion to a partially tumbled or fully tumbled attitude will be helped by an interference such as glancing off the spine. However, given the distance travelled by that particular bullet, it would have tumbled regardless of which of the two paths it had followed. In the straight-through instance, the rate at which tumbling progressed to the base-first attitude was principally a function of the rpm of its spin. In the dog-leg instance (off the spine) the straight – through situation was modified by how much encouragement the glancing had given to the progression of the tumbling. Captain Graham, being totally unaware that the bullet had been found and that it bore, according to the man who found it, a sharp indentation, and because of the rudimentary knowledge of ballistics in those days, had considerably over-simplified the situation.

In the light of todays knowledge, Captain Graham’s error is easily explained. If one looks at a bullet travelling a ‘short’ distance through, say, a limb, and being provoked into early tumbling by deflection or glancing off a bone, the point of exit may well coincide with the maximum extension of the temporary cavity which is then unable to close and thus remains open in the form of a horrendous wound. It would appear it was this sort of injury to which Captain Graham was referring.

With a bullet travelling a longer distance through a body, as in von Richthofen’s case, the temporary cavity had time to close down again by the pressure of the surrounding tissue. The exit wound therefore is considerably smaller. Ballistic pathologist. Doctor David King, pointed out to the authors that the exit wound, as described on von Richthofen’s body, conformed exactly to what he would have expected to see resulting from a Spitzer bullet having taken a long path laterally through his trunk.

The sketch on page 84 shows this and a fuller explanation will be found in Chapter!2.

The cause of death had definitely been established; a single bullet through the chest which had caused massive damage to vital organs in its path. Whether, as it tumbled, it had passed in a straight line from entrance to exit points or had dog-legged, the final result would have been the same although the organs damaged and the symptoms would have been different. Downs gave

|

|

no argument and со-signed the report which, although obliquely mentioning his suspicion, presented no opinion against it.

The next morning, Monday 22nd, they wrote the following combined report to 22 Wing RAF HQ:

We examined the body of Captain Baron von Richtoven [sic] on the evening of the 21st instant (April 1918). We found that he had one entrance and one exit wound caused by the same bullet.

The entrance wound was situated on the right side of the chest in the posterior fold of the armpit and the exit wound was situated at a slightly higher level nearer the front of the chest, the point of exit being about half an inch below the left nipple and about three quarters of an inch external to it. From the nature of the exit wound, we think that the bullet passed straight through the chest from right to left, and also slightly forward. Had the bullet been deflected from the spine, the exit wound would have been much larger.

The gun firing this bullet must have been situated in roughly the same plane as the long axis of the German machine and fired from right and slightly behind the right of Captain Richtoven. (1)

We are agreed that the situation of the entrance and exit wounds are such that they could not have been caused by fire from the ground.

The wing span of an aeroplane in those days was greater than the length of its fuselage. The long axis referred to would be close to that of an imaginary line drawn along the middle wing of a Triplane from tip to tip. When the ‘joystick’ was pushed forward or pulled back, the Triplane would pivot around that line, hence the name axis. Depending upon the attitude of the Triplane at that time, the long axis could have been inclined in any direction. The two MOs, who are using engineers’ terminology, are stating briefly that the right-hand side of the Triplane was almost squarely facing the gun that fired the fatal shot wherever that gun may have been. They are relating the gun to the attitude of the aeroplane – not vice-versa.

Some, who have not realised the import of the long axis statement in the third paragraph, have claimed (mistakenly in the authors’ opinion) that the final sentence contains the unwarranted assumption that a fighter aeroplane always flies straight and level, and Captain Graham and Lieutenant Downs have been accused of both outright bias and of gross stupidity because of it. However, a moment’s reflection suggests that the MO of an entire Wing, which included several squadrons of fighter aircraft, would be well aware how they were flown and would be most unlikely to imply such nonsense, especially in writing to a superior officer. There surely had to be more to it than that.

If one takes the same starting point as being

(1) It is amazing how many people at this time did not know how to spell Richthofens name. We have had Reichtofen. RichthofFen and now Richtoven.

We examined the body of Captain Baron VON

RICHTOVEN on the evening of the 2iet instant. We found that he had one entrance and one exit wound caused by the same bullet.

The entrance wound was situated on the right

eide of the oheet in the posterior fold of the armpit: the exit wound was situated at a slightly higher level nearer the front of the chest, the point of exit being about half an inch below the left nipple and about three quarters of an inch external to it. Prom the nature of the exit wound, we think that the bullet passed straight through the oheet from right to left, and also slightly forward. Had the bullet been deflooted from the spine the exit wound would have been much larger.

The gun firing this bullet must have been

situated in roughly the same plane as the long axis of the German maohine, and fired from the right and slightly behind the right of Captain RICHTOVEN.

|

We are agreed that the situation of the entranoe

and exit wounds are such that they oould not have been caused by fire from the ground.

Capt. R. A.M. C.

M. O.i/o 22nd Wing, R. A.F

|

|

|

|

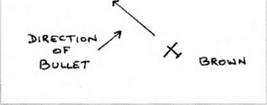

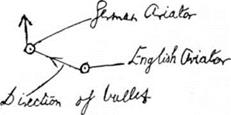

Lt Downs’ Sketch Clarified

|

Vo*» Richthofen

|

the situation before the MO’s, it becomes obvious that they would not have any reason to make a general statement, as they had only one ground fire claim to deal with. To them, the fatal shot, not being a frontal or semi-frontal wound through the chest with exit through the back, eliminated the claim of the 53rd Battery. There was also the matter of the tight pattern fired by a Lewis gun at close range versus the single bullet which struck the Baron, and a ground-based Lewis gun was much steadier than one mounted on a vibrating aeroplane.

The final statement was as far as they were prepared to go; anything deeper was dangerous territory. RAMC Lieutenants and Captains do not pre-empt Army Medical Services Colonels, unless they wish a posting to some far away place with a strange sounding name and lots of flies! The statement represents the conclusion of their examination; it is not just a comment. Once it is read as referring to the claim by the 53rd Battery, their report becomes clearly impartial.

The sketch which they appended to illustrate the third paragraph (The gun firing this bullet….), required knowledge of the bullet hole in the right-hand side of the fuselage at the front end. Such knowledge could only have come from a briefing on that point, probably from Major Blake who would have learned about it from Captain Ross, his Armament Officer. The snag was that the lines on it did not exactly match the angles from which Captain Brown or Lieutenants Barrow and Banks claimed to have fired at the Triplane. However, who could be sure of the exact attitude of the Triplane in the air at that time? There was the added complication of the harness which the pilot had loosened to work on his defective machine guns. Was he sitting erect or leaning forwards when he was struck? There is no indication that his right 86 arm may have been raised as he worked the cocking handle of his guns, for at the moment he was struck he would already have given up on that and have been in the act of pulling up and away. The ‘hot potato’ of 209 Squadron versus 3 AFC remained on the griddle.

Unnecessary confusion has been created by the paraphrasing of the conclusion to the point that it is common belief that the words are: ’…. the shot could only have been fired from the air.’ This completely alters the point that the MOs were trying to make (rightly or wrongly) that the 53rd Battery’s claim was inconsistent with the facts.

A copying error occurred in the transcript sent to С E W Bean, the Australian Official Historian, so that it read: ’…. below the right nipple…" instead of: ‘…. below the left nipple…’. Either that or the writer was mentally viewing von Richthofen from the front where the left nipple would be to the writer’s right. Bean caught and corrected the slip but some of the others, who received copies of the flawed transcript, used it verbatim. The origin of statements such as: “Von Richthofen was shot in the back of his right shoulder and the bullet exited through his right breast…’ , becomes obvious.

By the morning of the 22nd, 3 AFC’ had withdrawn its claim; the time of the encounter of their RE8s with the Triplanes was too early. By default, this left Captain Brown as the remaining contender – from the air.

At some time that morning, the Recording Officer of 209 Squadron (Lt Shelley), obtained an Army Form W3348, Combats in the Air (reports) and re-typed Captain Brown’s earlier one in a more presentable manner. The subscripted words: ‘.. and Lieut. May.’ became part of the line itself. No words were changed: that would have been illegal, but some additions were typed into the top left hand corner, viz:

Engagement with red triplane

Time: about 11-00 a. m.

Locality. Vaux sur Somme

Captain Brown signed it. Major Butler approved it and this time annotated it: One Decisive.

The better-looking report was also dated 21 April 1918 and was submitted to 22 Wing on the 22nd together with post-1601 hours documents referring to the 21st. In the Air Ministry file it is numbered later than the 209 Squadron reports received by the 5th Brigade on the 21st.

Also on 22 April, 3 AFC Squadron submitted its War Diary entry for the 21st. The relevant portion is transcribed below:

Two machines of this Squadron encountered the Circus about the same time as the Baron was shot down although they were not concerned in the actual shooting down of the celebrated enemy. Lieuts, Garrett and Barrow, and Lieuts. Simpson and Banks were proceeding to the line for the purpose of photographing the Corps front when they saw the enemy triplanes approaching. Lieut. Simpson and Banks were the first to be attacked by four of the triplanes. The observer fired 100 rounds at point blank range at the E. A., one of which was seen to separate and go down. The others withdrew and attacked Lieuts. Garrett and Barrow. The observer in this case got 1n 120 rounds Lewis, in bursts and another of the E. A. was seen to go down out of control. Both pilots then proceeded over the line and carried out their task of photographing the whole Corps front

In the meantime reports had come from the Infantry that one of the triplanes shot down in the general combat which had ensued between our scouts and the enemy circus after they had been driven off by the the RE8s of this Squadron, was that of Baron von Richthofen. The Lewis gunners of the 5th Divisional Artillery, A. I.F. claimed the honour of firing the shot which brought him down, but after the matter had been carefully investigated, the award was made to Captain Brown, of No. 209 Squadron, RAF.

The entry was written by the RO, Captain E G Knox (a former Sydney journalist) and signed by the CO, Major Blake. The phrasing indicates that 3 AFC was no longer pursuing Lieutenant Barrows claim. Another interesting fact at this early stage is that Knox apparently knows, or at least indicates, that the Baron was killed by a single bullet! It also makes the first known official reference to an ‘investigation’. Major Blake will return to the story in the final chapter.

Any investigation which took place in the evening of the 21st or the morning of the 22nd would hardly have all the facts at its disposal. Such a hurried affair clashes somewhat with the impression given on Browns plaque in Toronto where he refers to a Board, and with the statements made by Foster, May and Mellersh on the same subject. The clash has complicated earlier attempts to study what some have referred to as the Official Board of Enquiry for the descriptions appear to refer to two different meetings.

The solution to the puzzle is actually quite simple; there were two different meetings. The first one was on the evening of the 21st and the second one on 2 May, the day after Captain Brown entered No.24 General Hospital at Etaples. The details appear later in Chapter 15.

The Graham/Downs medical examination report was not a model of precision. The wording – ‘a slightly higher level’ and ‘in roughly the same plane’ could without any difficulty have been made clearer. The second example given is particularly deficient in that ‘above’ or ‘below’ is not specified. The report also contains two’abouts’ and one ‘we think’. Even worse, they had missed an injury caused by the very bullet whose path they had studied.

Historian Frank McGuire told the authors of an amusing story about an attempt (not his) to locate Captain N C Graham after the war in order to obtain his first-hand comments on the examination. A RAMC Captain Graham was found without too much difficulty and he said that he remembered the incident quite well. Unfor-tunately the story which he told matched an inaccurate one published some time before. Further investigation revealed that his initials were not N C, nor had he been in France in April 1918!