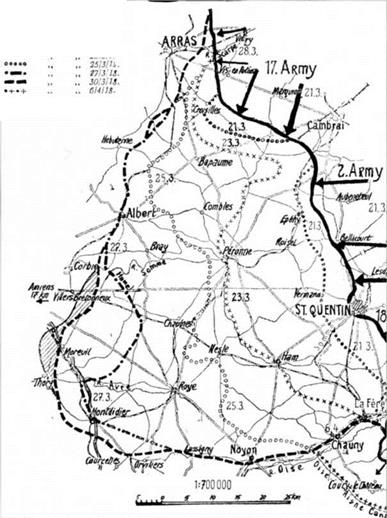

CHAPTER ONE The Military Situation

Towards the end of March 1918 the LudendorfF Offensive (Operation Michael), Germany’s final effort to end WWI favourably before the weight of American arms could be felt, had ceased to make progress after a successful start. The last assault made had attempted to capture the city of Amiens but on 3*» March the Australian Imperial Force had halted the German advance ten miles short of its objective. By the next morning the Australian infantry was starting to run short of ammunition and might soon have been forced to withdraw. 3 AFC Squadron came to the rescue. Its RE8s tlew over the Australian positions at an extremely low height and the observers tossed out small containers of ammunition from the rear cockpits to the troops. With pieces of old blankets tied with rope around the containers, sufficient ammunition survived the drop unscattered to save the situation.

Private Vincent Emery was one of the recipients of this largesse. According to his later testimony, he was down to the last two panniers of ammunition for his Lewis gun as the re-supply came from the skies. His helpers were able to gather enough undamaged drums for their gun to remain in action. This was the first known air-to – ground ammunition supply drop.

In early April the German High Command decided to renew the attempt to take Amiens. Troops and supplies were being concentrated in the area of the town of Le Hamel, situated just south of the Somme, 18 kilometres due east of Amiens. Although Le Hamel itself was protected from an Allied counter-attack by trenches, there was no continuous front line. The German forward defences were merely a series of strong points where their advance had been halted. The gaps between the strong points were linked by barbed wire and covered by machine-gun positions and trench mortars.

In the first fortnight of April the Allied forces had constructed a similar series of strong points. The gaps between them, from Corbie to Sailly—le— Sec, had mainly been filled by Vickers machine – gun crews who had dug their weapons into camouflaged and sheltered positions along the north bank of the Somme. This tall bank forms part of the south edge of the Morlancourt Ridge.

The Ridge itself, from a geographical point of view, is composed of the high ground between the River Ancre to its north and the Somme to the south.

In this Sector the main weapon, both for the Germans and the Allies, was artillery. It was one of the rare occasions in the First World War that the Allies enjoyed the strategic advantage of holding the high ground. Two Australian Field Artillery Batteries, the 53rd and the 55th, each equipped with six 18-pounder guns, were situated in a field just below the top of the Morlancourt Ridge on the Ancre (north) side of the crest, with the town of Bonnay behind them. just across the river. They were therefore completely hidden from the German artillery observers on the south side of the Somme, beyond Le Hamel.

The eyes of the two Australian Field Artillery Batteries were several carefully sited Forward Observation Posts (FOPs) whose crews were equipped with binoculars, a telescope and a field telephone. The best of the German observation positions was located in the church tower in the town of Le Hamel. The German observers enjoyed a panorama of Allied territory to their north and north-west which included an excellent view of the ruins of an old windmill silhouetted against the skyline some five kilometres away. This excellent German view of Allied territory was countered by the 53rd Battery FOP located in three short trenches near the ruined stone windmill. Being dug a little below the crest of a section of Ridge which jutted out to the south, the three trenches gave an overview of Le Hamel and German-held territory around it. The clearest and most easily recognised object was the Hamel church tower. The continued existence after the war of both the ruins and the tower, suggests a tacit modus vivaidi between the opposing observers.

To the left of the windmill FOP trenches sat a small forest known as Welcome Wood, which blocked the view to the north-east but in that direction lay Allied-held territory. In a large field just behind the windmill (to the north of it) lay an Advanced Landing Ground (ALG) used recently by aircraft of 3 Squadron, Australian Flying Corps, whose main base was at Poulainville five miles

![]()

![]()

![]()

Ground gained in П2Л German attack on 24 HI 4.

Ground gained in П2Л German attack on 24 HI 4.

(8 km) north of Amiens. However, now that the German lines were so close, this had been abandoned. The German attack was planned for 24 April and would be repulsed by the Australians at Villers Bretonneux, to the south-west of Le Hamel.

Two mobile 18-pounder guns of the Royal Garrison Artillery were operating along the Corbie to Bray road, which ran along the top of the Morlancourt Ridge, in a more or less west to east direction. Their FOP was dug into a field just to the south of the road. The field sloped away gently towards the Somme, then suddenly the incline became quite steep. The observers, who were near the Sainte Colette brickworks, at the high end of the gentle slope, had a clear view of the German-held territory west of Le Hamel from

one half to five miles away (0.8 — 8 km). They were very well positioned to deal with a German attempt to move forces or supplies towards the river or the town of Corbie. Although the skyline created by the change from a gentle slope to a steep gradient blocked the River Somme below from view, this was of no great consequence as an observation trench was being prepared near the edge of the slope by the 51st Battalion. The FOP observers could move forwards to join them if required. The surface of the gently sloping field going back as far as the road was clearly visible in the German telescopes. Prudent men avoided forming groups there in daylight. Vehicular traffic used the road only at night.

From the Sainte Colette FOP the view to the east was blocked ‘A miles (2.5 km) away by Welcome Wood. The village of Sailly – le-Sec, in the distance behind the wood, could not be seen. Similarly, the brow of the Ridge in front (south) of the post completely hid the nearby village of Vaux-sur-Somme and the river itself from view.

The opposing armies stayed tar enough apart for one to be relatively safe from rifle or machine – gun tire from the other. However, it was wise to avoid bunching-up in groups large enough to provoke an ever-watchful artillery observer into picking up his telephone. German shells continually cut the telephone wires between the various levels of headquarters and their outposts. Daily repair work was required, especially alongside the Corbie to Bray road which was shelled nightly (nicknamed ‘The Evening Hate’) by pre-ranged guns in attempts to disturb and disrupt the supply vehicles on their way to the forward defence positions. A ‘wag’ with a theatrical background claimed that the Germans staged a

|

|

THE MILITARY SITUATION

Top left: Corbie to Laurette-Cerisy showing major points and where the day’s air battles would be fought.

Top left: Corbie to Laurette-Cerisy showing major points and where the day’s air battles would be fought.

Top right: Manfred von Richthofen and his father Major Albrecht von Richthofen.

Left: Troops walking along the Somme Canal, looking east.

show called The Evening Hate’ twice nightly with a matinee on Saturdays.

The opposing air forces were primarily concerned in discovering the dispositions of the others’ ground forces. The presence of any photographic reconnaissance RE8 aeroplane near Le Hamel or of a German Rumpler CV near Bonnay was a serious matter. In early April, both sides took steps. 209 Squadron RAF (formally 9 Naval Squadron RNAS until the RFC and RNAS merged into the RAF on 1 April 1918). commanded by Major С H Butler DSO & Bar, DSC, and equipped with Sopwith Camel fighters of the latest type, was ordered to Bertangles aerodrome on 7 April, as reinforcement for 22 Wing RAF. Butler had received his DSO & Bar fighting against German Gotha bombers raiding England in the summer of 1917, both awarded within a fortnight.

At the same time, the German High Command ordered von Richthofens Jagdgeschwader Nr. I to Сарру aerodrome on 12 April. Abbreviated to JGI it was better known to

the Allies as Richthofens Flying Circus, and comprised fourjastas, Nos 4,6. 10 and 11 .All were equipped with Fokker Triplanes, although they also had a few Albatros DVa machines. For some time Richthofen had been awaiting the arrival of the new Fokker DVI1 biplane, which he had test flown in Germany, but he was destined never to fly one in front line service.

On the same day that von Richthofen was killed the British captured a document which explained his presence on that part of the front. It read as follows:

‘From Kofi (Kommandeur de Flieger)

HQ. 2nd Army, to Commander JGI.

Strong enemy opposition is preventing flights west of the River Ancre.

I request that this air barrier be pushed back to permit reconnaissance flights as far as a line between Marceux and Puchevilliers.’

(The line mentioned was about 20 kilometres behind the front line.)

Von Richthofen, despite being Germany’s premier

Australian machine gunners take up positions near Vaux-sur-Somme, 30 March 1918.

Australian machine gunners take up positions near Vaux-sur-Somme, 30 March 1918.

fighter ace, having downed his 79th and 80th opponents on 20 April, was still only a Rittmeister, ie: cavalry captain. This was because his father, a former army officer now brought out of retirement for service during the present war, held the rank of major. In Germany a son could not hold a rank higher than a father on active service.

On the morning of 21 April, the two rostered anti-aircraft machine gunners of the 53rd Battery, Gunner Robert Buie and Gunner William James ‘Snowy’ Evans, had prepared their Lewis machine guns. Their position was just beyond the top on the north-western slope of the Morlancourt Ridge, at the north end of the line of the Battery guns; they were passing time by playing poker nearby.

The duty officer at the windmill FOP site was Lieutenant J J R Punch; his telegraphist was Gunner Fred Rhodes. The Sainte Colette FOP was occupied by Lieutenant Turner and his signaller Gunner Ernest Twycross RGA. Five other signallers. Privates Dalton, Elix, Harvey, Newell and Ridgway, were at work on the telephone lines in the Sainte Colette area.

In a short trench near the brickworks, an expert anti-aircraft machine-gun crew, Private Vincent Emery, a trained anti-aircraft gunner, and his helper Private Jack Jeffrey, had their Lewis gun prepared in case a daring German flyer tried a “strafe and run’ attack on the Corbie-Bray road. Private Jeffrey was also a well experienced infantry support machine gunner who had been decorated with the Distinguished Conduct Medal for bravery.

Lieutenant-Colonel J L Whitham was in charge of the 52nd Battalion stationed in the village of Vaux-sur-Somme from which position

he could easily see the Le Hamel church tower to the south-east and the ruins of the windmill to the north-east. The 51st Battalion, also under Whitham, was manning defences on the slope of the Morlancourt Ridge between Vaux and Sainte Colette. A platoon of this Battalion, under Lieutenant R A Wood, was working near the lip of the Ridge restoring an old trench, said to have been dug much earlier by the French, so as to have it ready for action when the renewed German attack came. This trench held a commanding view otVaux below. It would be perfect for directing the fire of the Battalion’s machine gunners who were dug-in on the slope ahead.

Sergeant Gavin Darbyshire was supervising a party of soldiers repairing pontoon bridges across the Somme canal. That morning they were repairing one situated behind a large farmhouse on the south bank, half a mile before the canal makes a sharp turn from west to south prior to reaching the town of Corbie. If Lieutenant Wood were to direct his binoculars down the slope to the south-west (his right) he would be able to watch them at work.

That morning too, at Bertangles airfield, north of Amiens, Captain Roy Browns mechanics attached two long coloured streamers to the elevators of his Sopwith Camel, B7270. He had been designated by the CO, Major Charles Henry Butler, to lead 209 Squadron on patrol that day. 209’s other flight commanders this morning, Captain Oliver LeBoutillier, an American, and Lieutenant Oliver Redgate, from Nottingham, England, a deputy flight leader, had a single streamer attached to the rear interplane strut on both sides of their machines. (The Squadron’s senior flight commander. Captain S T Edwards DSC’, a Canadian, was on leave in England.)

Some 35 kilometres due east of Bertangles, on the German airfield at Сарру. JGI’s commander, Manfred von Richthofen, elected to lead Jagdstafl’el (Jasta) 11 that morning. The displaced Staffelfiihrer, Leutnant Hans Weiss, (himself standing in for the brother of the Baron, Lothar von Richthofen, wounded on 13 March), would accompany him on the extreme right of the formation. A German account disagrees with the arrangement of the pilots between the two flights. This is explained in Appendix C>.

With the exception of Major Butler, all the above-mentioned persons would become involved in a chain reaction provoked when the morning cloud, mist and drizzle cleared sufficiently for both sides to send photographic reconnaissance aircraft aloft.