Deadlock Before Moscow

|

D |

uring the latter half of July 1941, the German Army Group Center was occupied in a huge battle in the Smolensk-Rogachev area. Smolensk had been captured, and twenty Soviet divisions had been surrounded in that area. But the Smolensk pocket had not been closed tightly, and the desperate Soviet forces escaped to the east through a narrow gap east of the city. Parts of Luftflotte 2 fell on these forces, with devastating results. Terrible scenes were displayed on the ground, with panicked Soviet troops fleeing to the east, in any vehicle or by foot, passing scores of dead and wounded, subject to incessant Luftwaffe dive-bombings or strafings. Nevertheless, more than ten thousand Soviet troops managed to escape from the Smolensk pocket, mainly at night. At Yelnya, fifty miles to the southeast, a new Soviet counterattack pushed back the 10th Panzer Division. To the west of Smolensk, at Orsha and Mogilev, other large, surrounded contingents of Soviet troops fought to the bitter end.

With fewer than four hundred aircraft remaining in first-line service in the central combat zone, there was little the VVS could do to support these doomed troops. The bulk of these air forces was concentrated in close – support missions at Yelnya.

At this point the German High Command decided that the time was right to divert a large part of its bomber fleet to terror attacks against the Soviet capital. Already, on July 8, Hitler had ordered Hermann Goring to level Moscow and Leningrad to the ground—“to make sure that there will be left no inhabitants that we will have to supply during the winter.”1 The final order for the implementation of these terror raids came with the Fuhrer’s

|

Order No. 33 of July 19, 1941. Bomber units, including KG 4, KG 28, and KGr 100, were brought in from western European to strengthen the attack force.

But the plan to devastate Moscow from the air became a large failure, quite comparable to the air offensive against Great Britain the previous year. The Soviet defense forces simply were too strong. As the air offensive against Moscow was initiated, General-Mayor Mikhail Gromadin’s Moscow Air Defense District (Moskovskaya Zona PVO) had 585 fighters at its disposal (170 MiG-3s, 95 Yak-ls, 75 LaGG-3s, 200 I-16s, and 45 1-153s). The fighters alone were divided among twenty-nine fighter regiments in 6 IAK/PVO, commanded by Polkovnik Ivan Klimov. Furthermore, General-Mayor Gromadin had concentrated 1,044 AAA guns and 336 antiaircraft machine guns in and around the Soviet capital.

The fighting spirit of Moscow’s defenders was even more important than the material strength. “I swear to you, my country, and to you, my native Moscow, that I will fight relentlessly and destroy the Fascists,” read the

oath sworn by the fighter pilots assigned to the capital’s PVO. Such patriotic manifestations should not be underestimated in a country with a population subjected to a constant deluge of propaganda based on “revolution-і ary unselfishness,” as was in the young Soviet republic. In fact, the first significant Soviet victory of the war was achieved in the air over Moscow.

The initial air raid against the Soviet capital was launched during the evening on Monday, July 21, when 195 bombers—Ju 88s from KG 3 and KG 54; He Ills from KG 53, KG 55, KG 28,1I1./KG 26 and KGr 100; and Do 17s from KG 2 and KG 3—were concentrated against Moscow. They immediately encountered a strong defense composed of 170 Soviet fighters sent to intercept the raiders. Heavy air fighting took place in the Searchlight Concentration Zone in the Solnechnogorsk – Golitsyno area northwest of Moscow. The first kill was scored by Starshiy Lcytenant I. D. Chulkov of the MiG 3-equipped 41 1AP. Chulkov claimed an He 111 at 0210 hours. The Do 17 piloted by Leutnant Kurt Kuhn of

9./KG 3 was brought down by the famous test pilot Kapitan Mark Gallay. When captured Kuhn attempted to hide the fact that he had bombed Moscow claiming that his bomber had carried no bombs.

Nearer Moscow, the German bombers were met by heavy AAA fire. In total, the antiaircraft guns of I Korpus PVO reported the expenditure of 29,000 artillery- shells and 130,000 machine-gun bullets during this raid. “The night raids against Moscow – w-ere the most difficult missions that I carried out on the Eastern Front,” recalls Oberleutnant Hansgeorg Batcher, the Staffelkapitan of L/KGr 100. “The antiaircraft fire was extremely intense, and the gunners fired with a frightening accuracy.” Batcher would survive more than 650 bomber sorties between 1940 and 1945, a higher number than any other German bomber pilot. Most of these sorties were flown on the Eastern Front.

At the cost of six or seven aircraft shot down, 104 tons of high explosives and 46,000 incendiaries w-ere dropped by the attackers during this first raid. These caused heavy losses among the civilian population. But the real aim of the mission—to burn the Kremlin to ashes— failed completely. The bombs simply could not penetrate the thick, seventeenth-century roofs on the main buildings in the Kremlin.

The attack was repeated with 115 bombers the following night. While the 1-16 pilots of 27 IAP claimed three Ju 88s shot down, Mladshiy Leytenant A. Lukyanov of 34 IAP managed to bring down his second bomber in Searchlight Concentration Zone 5. The Germans admitted to the loss of five bombers during this raid.

Due both to the strong Soviet defense and the difficulty of keeping such a large portion of the declining German bomber force away from the growing difficulties at the front, the number of aircraft participating in each raid decreased from 100 on the third night to 50, 30, and finally no more than 15 on successive missions. Within a short time the trumpeted Luftwaffe offensive against Moscow had been reduced to mere nuisance raids.

The most successful Soviet fighter pilot during the brief “Air Battle of Moscow” was Kapitan Konstantin Titenkov, who scored one bomber on each of the first four raids, for which he was decorated with the Order of Lenin and the Golden Star as a Hero of the Soviet Union.

By this time the bomber units of Luftflotte 2 w-ere launched both day and night against Soviet troop columns and lines of communication in the rear of the

|

|

Oberleutnant Hansgeorg Batcher was appointed Staffelkapitan of 1./ KGr 100 in July 1941. On July 21,1941, he flew against Soviet troop concentrations in the Yelnya Bulge. On the following night, he participated in the first air raid against Moscow, Operation Klara Zetkin (ironically named after a famous German Communist leader). Batcher would survive a higher number of combat missions than any other Luftwaffe bomber airman in World War II, and today lives a quiet life near Hannover. (Photo: Batcher.)

Smolensk Front, as well as in close-support missions. Particularly heavy raids were flown against the Dnieper bridges at Smolensk to create the preconditions for surrounding Red Army troops in the area.

A gradual recovery – of the VVS was noticed during the second half of July. Reinforcements brought in included 120 bombers of 3 BAK/DBA and 153 aircraft from General-Mayor Boris Pogrebov’s VVS-Reserve Front At the same time, a new Red Army command, the Central Front (incorporating an air force mustering merely seventy-five aircraft) w-as assembled between the Western and the Southwestern fronts. WS-Western Front received more than 900 aircraft during July. 47 SAD

(including 129 IAP, equipped with the modern MiG-3 fighters, and 61and 215 ShAP, both equipped with Il-2s) and reinforcements to 43 IAD were located close to the front.

(including 129 IAP, equipped with the modern MiG-3 fighters, and 61and 215 ShAP, both equipped with Il-2s) and reinforcements to 43 IAD were located close to the front.

Obviously, the Soviet bo mix: r force had not learned their lesson completely yet. An Eskadrilya from 411 ВАР/ OSNAZ arrived to the front with ten Pe-2s on July 22 and carried out its first mission early the next day, when five Pe-2s were sent out to attack Shatalovo Airdrome between Smolensk and Rosiavl. Intercepted by Bf 109s, all the Pe-2s were shot down.2 Two Pe-2s were claimed by Feldwebel Kurt Hoppe and Unteroffizier Hans Fahrenberger of 8./JG 27 north of Yartscvo at about 0500 hours. Later that day, the remaining five Pe-2s of the 411th went for Shatalovo again, this time escorted by four LaGG-3s from 239 LAP. Three Pctlaykovs were lost, two of them recorded as the forty-third and forty – fourth victories of IV./JG 51’s indefatigable Leutnant Heinz Bar. Finally, on the morning of July 24, the last two Pe-2s of this unit were dispatched against German troop columns. Despite the presence of four escorting LaGG-3s, both Pe-2s were shot down by Bf 109s, and one of the Il-2s was possibly the twenty-third victory of Oberfeldwebel Heinrich Hoffmann of IV./JG 51.3

With the arrival at the front of Mayor Anatoliy Zhukov’s 32 1АР/43 LAD, equipped with thirty-six 1-16s, another Soviet fighter ace entered the battle, Mladshiy Leytenant Akimov. 32 LAP immediately started hunting the single-engine Messerschmitt fighters in the area, and not without success. In three days—on July 22, 25, and 26—Akimov scored four personal and two collective victories.

The new Soviet Reserve Front—comprising six fresh armies—launched a strong but inadequately prepared counteroffensive against Generaloberst Heinz Guderian’s Panzergruppe 2, to the east and southeast of Smolensk on July 25. This immediately drew the full attention of General von Richthofen’s Fliegerkorps VIII, whose Stukas and ground-attack aircraft conducted highly successful missions in this area on the following days. As the demands for air support from the ground forces increased, von Richthofen supplemented his ground-attack units with close-support missions carried out by his medium bombers. The Do 17s of L/KG 2 and IIL/KG 3 reportedly destroyed forty Soviet vehicles in the Belyy area, about eighty miles northwest of Smolensk, in a single day.4

Oberleutnant Johannes Steinhoff was the most successful pilot of IUJ 52 during Operation Barbarossa. Having scored eight victories overtl English Channel, he increased his tally to thirty-five by the end of Augu 1941. He was awarded with the Knights Cross on August 30,194 Steinhoff survived the war with a total of 176 confirmed victories and seiv; as the commander in chief of the Bundesluftwaffe before retiring on Ap 4,1974. He died on February 18,1994, in Bonn. (Photo: Steinhoff.)

The Soviet air support for the counteroffensive wr mercilessly butchered by the Bf 109s of Luftflotte 2.0 July 26, III./JG 27 claimed fifteen and IIL/JG 53 Pi As claimed twenty-one Soviet aircraft shot down (ii eluding five by Leutnant Erich Schmidt), most of thei DB-3 bombers. During one engagement this day, a whd Pe-2 Eskadrilya was wiped out. Seven Pe-2s from 5 SBAP, escorted by MiG-3s from 122 IAP, were out on bombing mission as ten to twelve Bf 109s attacked froi out of the sun. Within minutes, six Pe-2s and one Mi( 3 had been shot down. The seventh Pe-2 escaped wit severe battle damage but crashed on landing. A claii made by Oberleutnant Johannes Steinhoff, th Staffelkapitan of 4./JG 52, on July 26 for “Vultee V-ll

![]() probably was one of the new 11-2 Shturmoviks of the badly mauled 4 ShAP.

probably was one of the new 11-2 Shturmoviks of the badly mauled 4 ShAP.

The pilots of 32 1AP claimed to have shot down five Bf 109s on July 26. Luftflotte 2 actually recorded eight Bf 109s lost—two each from 1I./JG 52 and 1I.(S)/LG 2, three from JG 51, and one from 1I1./JG 53. Among the personnel losses was Feldwebel Gerhard Gleuwitz, a twelve-victory ace from 6./JG 52. Gleuwitz was injured in a forced landing near Lassma. In total, the Luftwaffe filed no few’er than twenty-eight of its own aircraft as shot down on the Eastern Front on July 26.

During the last week of July, the battle in the central combat zone was similar to a naval battle. Throughout the Roslavl-Velikiye Luki-Smolensk triangle, German and Soviet troops were involved in fierce fighting without any clear front lines. At this point the close-support units of Fliegerkorps II and Vlll had been brought forward to airfields in the immediate vicinity of the battlefield. They were thus able to intervene within minutes as soon as new critical situations arose on the battlefield. One of the most successful among these units was SKG 210, which claimed to have put 823 Soviet aircraft, 2,136 motor vehicles, 194 artillery pieces, 52 trains, and 60 locomotives out of commission on the ground between June 22 and July 26. Due to the confused scene on the ground, Stukas and ground-attack planes frequently raided German troops.

The location close to the front posed great problems for the Luftwaffe ground-support units. Obsert Hermann Plocher noted, “The ground situation changed so often

that the Luftwaffe units generally did not know when they took off whether they would be able to land at their old fields after the sortie.’” Time after time, the approach of Red Army ground forces compelled the close-support air units to defend their own bases.

On July 26, Panzergruppe 3 managed to isolate the attacking Soviet Sixteenth and Twenty-first armies northeast of Smolensk. With the simultaneous fall of the Mogilev and Orsha pockets, the Germans were able to move considerable infantry forces forward. At this point the Germans reported that 185,500 Soviet soldiers had been captured in the battle in the Smolensk area.

Fighting the increased presence of the VVS in the air, 1I1./JG 53 Рік As tore up three successive bomber formations on July 27, shooting down fourteen twin – engine aircraft. The pilots of III./JG 27 downed another nineteen. Returning in greater strength, the Soviet bomber units lost ten more planes on July 28. On July 29, IV./ JG 51’s Leutnant Heinz Bar reached the fifty-kill mark when he blasted a DB-3 and an SB out of the sky.

While the Stukas and ground-attack aircraft were directed to annihilate the surrounded Soviet forces in the Smolensk pocket, the bomber units of Luftflotte 2 concentrated on roads and railways leading from the east to the Bryansk-Vyazma-Velikiye Luki line. During the final days of July, the Kampfgruppen of Luftflotte 2 reportedly destroyed 126 trains and 15 bridges during interdiction missions. On July 30 the important railway junctions at Orel, Korobets, and Stodolishche were subjected to heavy Luftwaffe raids.

Day in and day out, the Soviet fighters were in action over the battlefield to relieve pressure on the ground forces. Most engagements ended to the disadvantage of the VVS, but at least the crack 43 LAD managed quite well, but at a high price. On July 30, four of 32 LAP’s I-16s came across sixteen Bf 109s and claimed three shot down. Possibly counted among the victims of 321AP was Leutnant Hans Joachim Steffens, a 5./JG 51 ace with twenty-two victories to his credit. As the I-16s were returning from this mission, a lone Bf 109 struck the 1-16 quartet, shooting down one 1-16 and killing its pilot, and then making a quick escape.

That evening, the new commander of the crack 401 IAP, Mayor Konstantin Kokkinaki, appointed after Podpolkovnik Stepan Suprun’s death, led three MiG-3s on a fighter sweep over the front area. They were bounced by Bf 109s, and one MiG-3 pilot was shot down and killed while Kokkinaki and his wing man barely managed to escape with severe battle damage to their planes.

That evening, the new commander of the crack 401 IAP, Mayor Konstantin Kokkinaki, appointed after Podpolkovnik Stepan Suprun’s death, led three MiG-3s on a fighter sweep over the front area. They were bounced by Bf 109s, and one MiG-3 pilot was shot down and killed while Kokkinaki and his wing man barely managed to escape with severe battle damage to their planes.

On July 31, Luftflotte 2 was concentrated against three main targets: Soviet columns in the area between the Smolensk-Roslavl rail line and the highway to Vyazma; an attempted counterattack at Shatalovo, thirty-seven miles southeast of Smolensk; and the railway junctions mentioned above. Returning Luftwaffe crews reported that the Soviet casualties from these attacks could not be accurately estimated, but in reality they put seventy-three trucks, twenty-two tanks, and fifteen rail cars out of commission. l./KG 53 Legion Condor had two He Ills shot down by fighters near Vyazma, while an He 111 from 7./KG 53 force-landed with battle damage. During another engagement on July 31, the crack 401 IAP claimed two Bf 109s shot down against two MiG-3s damaged and one pilot injured.

All in all, 43 LAD, to which 32 and 401 IAP belonged, carried out 4,638 combat sorties between June 22 and August 2, 1941, claiming 167 aerial victories, with the loss of 89 aircraft.

The intensity of the air war during the Battle of Smolensk is clearly displayed by the number of sorties carried out by the belligerent air forces on this sector between July 10 and July 31—12,653 German and 5,200 Soviet.

Between July 29 and August 4 the airmen of Luftflotte 2 were credited with the destruction of 100 Soviet tanks, 1,500 trucks, 41 artillery pieces, and 24 antiaircraft batteries in the Smolensk sector alone. On August 5 the battle of annihilation at Smolensk ended, and another 310,000 Soviet soldiers marched into captivity.

While the Soviets continued to strengthen their defenses on the road to Moscow, Hitler issued a new directive on July 30. The new orders suddenly called for shifting the next main objective of Operation Barbarossa to the seizure of Leningrad.

Even before the battle of Smolensk had been completed, Fliegerkorps VIII was transferred from Generalfeldmarschall Albert Kesselring’s Luftflotte 2 in the central combat zone to join Luftflotte 1, to the north.

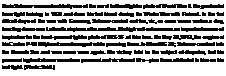

Generalfeldmarschall Albert Kesselring, who commanded Luftflotte 2 from № 1940 to 1943. “Smiling Albert” Kesselring was one of the best known and ; 6: ablest Luftwaffe senior commanders during World War II. He passed away ‘! К on July 16,1960, at the age of seventy-five. (Photo: Bundesarchiv.) 1

Luftflotte 2 was thus divided in half, with Fliegerkorps j К II remaining as the only German air cover in the central | | combat zone.

When the Soviet commanders noticed the dimin – j | ished enemy presence in the air, they took the oppor – 1 § tunity to step up WS activities. The large German air j I base at Shatalovo, between Smolensk and Roslavl, was s [ subjected to intensive and repeated Soviet air raids dur – 1

ing the first days of August 1941, but the fighters of JG 1

51 were able to score considerably against these raiders. j On August 2, Oberfeldwebel Heinrich Hoffmann, one І [ of the most successful aces in IV./JG 51, brought down J I three R-5s, one 1-15, and two R-10 bombers, bringing his і S personal score to thirty-three.6

Meanwhile, a serious crisis arose in German com – ] I

mand circles. Generalfeldmarschall Fedor von Bock, the commander of Army Group Center, and his two Panzer generals, Guderian and Hoth, wished to continue straight toward Moscow, but Hitler hesitated. The stiff Soviet resistance in the Smolensk sector had made the Fiihrer cautious. It took Hitler three weeks to make up his mind. During this time Army Group Center was left without any major strategic goal.

In this period the bomber offensive against Moscow also was ended. Returning vvithsmall forces against the Soviet capital on the night of August 6-7, I1I./KG 26 lost an He 111, which probably fell victim to a taran carried out by Mladshiy Lcytenant Viktor Talalikhin of 177IAP. Vasiliy Garanin, then a young Starshiy Lcvtcnant of the Moscow PVO, still has a vivid memory this spectacular nocturnal taran, which he viewed from the ground:

Everything happened very rapidly. Suddenly 1 saw

fire in the dark sky and a descending aircraft. 1

couldn’t judge whether it was one of ours or a German plane. The soldiers cried: “Parachute! Parachute!” 1 watched and saw the pale cloth of a parachute. I immediately ordered a vehicle to the place where the pilot would come down.

Suddenly a huge explosion was heard. Stunned, we could see a large pile of fire at the wall of a monastery. An enemy bomber had crashed only 100 to 150 meters from our staff position.

“It’s one of ours! One of ours!” We gathered around the pilot. He was injured in one of his hands. It appeared that he was from a PVO regiment stationed not far from us. We quickly brought him to safety.’

|

Mladshiy Leytenant Talalikhin had survived by bailing out. He inspected the crash site of the Нс 111 together with Starshiy Leytenant Garanin and a group of Soviet soldiers early the next morning. The bomber had buried itself six feet into the ground right next to

the monastery. Garanin recalls how Talalikhin picked up something from the ground and put it into his pocket as a memento. According to one Soviet source, the victorious Soviet pilot found the body of a dead lieutenant colonel among the dispersed remains of the bomber. Also according to this source, a corkscrew and a package of pornographic pictures were found in the pockets of the dead man’s uniform.8 According to German records, there was no Oberstleutnant aboard the downed bomber.

With the task of providing air support along nearly five hundred miles of the front, Generalfeldmarschall Kesselring realized that he could not afford to divert his precious bomber units to nuisance raids against Moscow. He decided to concentrate the bulk of his only remaining air corps, Fliegerkorps II, to the southern wing of Army Group Center, at Gomel, where Guderian’s tank units encountered two Soviet armies. Here the planes were deployed mainly against troop and supply transports in the Soviet rear area. One of the prime targets was the railway junction at Bryansk. Mustering only seventy-five operational aircraft by August 10,4 WS-Cen – tral Front in this area was not able to do much against this. In large part due to Fliegerkorps П, Generaloherst Guderian succeeded in cutting off twenty-three Soviet army divisions in the Gomel area by August 9. The battle lasted eleven days and resulted in the capture of 84,000 prisoners.

Meanwhile, the weak Luftwaffe forces remaining on the left flank of Army Group Center were opposed by increasing VVS activity. During air combat over the border area between Army groups Center and North at Velikiye Luki on August 8, 29 1AP claimed eight Messerschmitts and Junkers shot down. Downed by Soviet fighters, a Stuka pilot, Unteroffizier Siegfried Fischer of 6./StG 1, bailed out over enemy territory near Velikiye Luki. Despite severe burns, he managed to return to German lines.

On August 9, JG 51 claimed nine bombers shot down during a Soviet air raid against Shatalovo Airdrome. Leutnant Heinz Bar, who contributed three DB-3s to this latter success, was awarded with the Oak Leaves to the Knight’s Cross five days later. But most raids managed to evade German interception because the costly daylight raids by Soviet medium bombers were supplanted by low-level attacks by fighter-bombers or Shturmoviks. The regiments of 47 SAD and 43 LAD were divided into elements consisting of one or two Eskadrilyas, which made it possible to increase the number of flights. “We simply had no measure to counter these sudden attacks,” wrote Aders and Held. “The Russians learned from their losses: They climbed shortly before they arrived over the airfield, dived down on us, and gained such speed that the Rotte on duty’ was unable to catch them.”10 The brunt of the VVS attacks was concentrated against the German Ninth Army on the main road from Minsk to Moscow.

Obserst Hermann Plocher later wrote: “Especially troublesome were the continuous attacks upon the German front lines by Soviet ground-attack planes. Although these attacks were generally of relatively slight effect, they nevertheless influenced the morale of the ground forces. . .. The struggle against these ground-attack aircraft was very difficult because they approached from afar and at low level, flying singly, in two-plane formations, and in weak squadron strength; dropped their bombs on the front lines; and immediately turned back toward their own territory. Scrambling German fighters usually arrived too late to block the attack, and their pursuit of the Soviet ground-attack aircraft, which were retiring at low altitudes, was too costly for the unarmored German fighters because of the strong Soviet ground fire.”11

For the first time, the German fighter units lost control of the air. The combined effect of the sudden weakening of the Luftwaffe and the reinforcement of the VVS in this area can be read in the following laconic note from August 11 in the war diary of the German High Command: “Report from the Ninth Army. . . . The enemy enjoys air superiority in the whole army area."*’

Kesselring responded by launching He 11 Is, Ju 88s, and Do 17s in a series of renewed raids against the Soviet airfields in the area. Once again, a large number of Soviet aircraft was destroyed on the ground, which brought a temporary decrease in the VVS raids. On the other hand, the concentration of the Luftwaffe bombers against the Soviet airfields also came as a relief to the Soviet lines of communication, which made it possible for the Soviets to bring forward new troops and equipment to the front lines.

On demand from the High Command, the Luftwaffe dispatched yet another nuisance raid against Moscow on the night of August 11. This time the bomber crews encountered a new menace, twin-engine Petlaykov Pe-2s acting as night fighters. These Pe-2 bombers had been equipped with powerful searchlights to locate the enemy

|

bombers in the dark. The original intention was to use the Pe-2s as “flying searchlights” to assist the singleengine night fighters, but once the German aircraft were sighted, the eager Pe-2 pilots pressed home their own attacks with vigor. The success was immediate. Four German bombers were brought down by the Petlaykov night fighters on their first night out. Following this raid, the Germans decided to cancel the bomber offensive against Moscow.

More air raids would follow against the Soviet capi – tal-a total of eighty-seven took place between July 21, 1941, and April 5,1942—but the systematic air offensive had ended. Of seventy-six air raids during 1941, fifty – nine were carried out with no more than between three and ten planes. According to Soviet sources, air raids against Moscow’ through October 1, 1941, cost the Luftwaffe 173 aircraft (110 shot down by fighters and

60 by AAA, with another three destroyed in collisions w’ith the steel wires of the barrage balloons). This w;as a humiliating blow’ to the prestige of the Luftwaffe, particularly as it occurred just at the time when Soviet bombs w’ere starting to fall on the Reich’s capital itself.

Symptomatic of the soaring combat spirits among the Soviet airmen on the Moscow Front during this period was the success claim made by 129 LAP over the Yelnya bulge on August 20—nine German aircraft shot down. Farther to the north, Leytenant Luka Muravitskiy of 29 LAP claimed two Ju 88s shot down in a single engagement on the same day. A week later, Muravitskiy scored his tenth victory.

On August 23 Hitler finally made up his mind regarding Army Group Center. He ordered Guderian’s Panzergruppe 2 toward Kiev to support Army Group South. In two months’ time, Army Group Center had

|

Volume I: Operation Barbarossa. 1941

been reduced from the main force of Operation Barbarossa to a mere supplement to the two other army groups. Inasmuch as most of Fliegerkorps II remained with Guderian to the south, only limited German air units were left in the central combat zone.

At this moment the Red Army increased its pressure against the German Second Army in the bulge at Yelnva, to the south of the main Moscow-Minsk highway. The German fighters left in the central combat zone were totally outnumbered in the air. During one of these battles, on August 25, JG 51 lost one of its most outstanding pilots, Hauptmann Hermann-Friedrich Joppien, victor in seventy aerial combats. On August 30 two armies from General Armii Georgiy Zhukov’s Reserve Front launched a powerful counterattack at Yelnya. “Heavy Red air activity” was reported to the Gentian Army Staff: “Unequivocal Russian air superiority in the sector of the Second Army.”15 On September 1,1I./JG 51 was severely hit by a bombing raid against Shatalovo. One bomb struck the quarters of 4 Staffel, killing five and injuring many others. The next day, Unteroffizier Anton Hafner (6./JG 51) entered the following lines into his diary: “At six sharp, six biplanes (Curtiss) strafe us.

|

Feldwebel IRichard) Quante managed to shoot down two before he was himself brought down by machine – gun fire. He went down in occupied territory. Shortly afterward, another six bombers arrive at low level. Nine bombers dive out from the clouds. Our AAA fires with everything available. We couldn’t get any breakfast. The 8.8cm Flak force eight bombers to turn away. Then fighters attack from the side. We have to remain in the shelters. The sky is filled with Russian aircraft. Fifteen Russians are shot down.”

It took the Soviets no more than a week to push the German Second Army out of the Yelnya bulge and back across the Desna River. The immediate threat to Moscow was thus removed.

During two months of fierce air battles the VVS had displayed a remarkable capacity to withstand extreme losses. According to Soviet sources, 903 VVS aircraft were lost in the Smolensk-Yelnya sector between July 10 and September 10,1941.14 Even if the Bf 109s shot down rows of aircraft each day, the surviving Soviet fliers were back in the air again the next day. Without this stamina, the Soviet air forces would not have been able to give the air support that contributed decisively to bringing Hitler’s first offensive toward Moscow to a halt.

“The Red Air Force has not been defeated,” noted the war diary of JG 51 on the same day as Hauptmann Joppien was missing. By bringing in aircraft from other

parts of the USSR, replacements from aviation industry, and eleven hundred obsolescent planes from the flighttraining schools, the VVS was able to increase the number of first-line combat aircraft to thirty-seven hundred at the end of. August. Even if this was far below the impressive resources available at the front at the outbreak of the war, it meant that the VVS once again had managed to gain at least a numerical superiority in the air.

Nevertheless, the allocation of large numbers of inadequately trained airmen resulted in continued massive losses on the Soviet side. The deployment of better aircraft could not outweigh this crucial fact, which is clearly displayed by the records of the first 11-2 unit to see combat, 4 ShAP. By the end of August, 4 ShAP had carried out 427 combat sorties and lost 60 aircraft,15 a frightening loss rate of 14 percent. Despite massive replacements, the number of operational aircraft at hand in 4 ShAP dropped from fifty-six at the outbreak of the war to only two in late August. Handing these planes over to 215 ShAP, the surviving pilots of 4 ShAP were pulled out of combat.16 But to the Luftwaffe airmen – and not least, the German front-line ground troops—it would soon be clear that the fight with the Red Air Force had only begun.

By August 31, the accumulated losses sustained by the Luftwaffe on the Eastern Front had reached 1,320

combat reconnaissance planes destroyed and 820 damaged. In addition, 170 Army aircraft were destroyed, and another 124 were severely damaged. Ninety-seven transport, liaison, and other non-combatant aircraft were also lost.

After the disheartening defeats in June and July, optimism soared in Moscow. The inhabitants of the Soviet capital, who had lost 736 killed and 3,513 injured to bombing raids between July 22 and August 22, began to hope that the worst crisis was over. In their triumph, they noted the humiliating inability of the vaunted

Luftwaffe to maintain the air offensive against their city. They were aware that German ground forces stood fewer than 200 miles away, but at the same time they felt tran – quilized by the obvious fact that the Blitzkrieg along the road to the east had stopped. Many started to hope for an imminent turning point in the war.

For now, most Soviet and German observers turned their attention to the outcome of the Battle of Leningrad, selected by Hitler as the new prime objective of his invasion.

days and nights in a rubber dinghy in the Bay of Riga before finally reaching the shore near Mikelbaka on the northern tip of the Lithuanian mainland.

days and nights in a rubber dinghy in the Bay of Riga before finally reaching the shore near Mikelbaka on the northern tip of the Lithuanian mainland.

turned around. My wingman made another attack. Once again, the Russian turned and met him head – on. Damn, this was a tough fellow!

turned around. My wingman made another attack. Once again, the Russian turned and met him head – on. Damn, this was a tough fellow!

machine-gun fire, bomb explosions, and roaring aircraft engines.*34

machine-gun fire, bomb explosions, and roaring aircraft engines.*34

To the south, on the border between Army Group North and Army Group Center, a prolonged battle was being waged at Velikiye Luki, where a Soviet counterattack was halted with the help of Fliegerkorps VHL This resulted in the complete destruction of the Soviet Twenty-second Army. Here, 40,000 Soviet soldiers perished and 30,000 were captured, a high price for merely slowing the German advance against the sector between Lake Ilmen and Moscow. Operating over this battleground, the Bf 109s of I1I./JG 53 Рік As took a heavy toll of WS-Northwestern Front, reinforced to muster 174 aircraft on August 22. On August 25, Oberfeldwebel Stefan Litjens of 111.,/JG 53 repeated Oberleutnant Erbo

To the south, on the border between Army Group North and Army Group Center, a prolonged battle was being waged at Velikiye Luki, where a Soviet counterattack was halted with the help of Fliegerkorps VHL This resulted in the complete destruction of the Soviet Twenty-second Army. Here, 40,000 Soviet soldiers perished and 30,000 were captured, a high price for merely slowing the German advance against the sector between Lake Ilmen and Moscow. Operating over this battleground, the Bf 109s of I1I./JG 53 Рік As took a heavy toll of WS-Northwestern Front, reinforced to muster 174 aircraft on August 22. On August 25, Oberfeldwebel Stefan Litjens of 111.,/JG 53 repeated Oberleutnant Erbo Graf Kageneck’s previous feat by knocking another five Soviet fighters out of the air, including four “MiG-Is” (in reality probably MiG-3s).

Graf Kageneck’s previous feat by knocking another five Soviet fighters out of the air, including four “MiG-Is” (in reality probably MiG-3s).

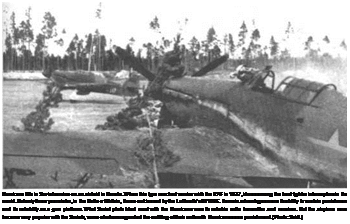

A fighter pilot of 13 IAP/VVS-KBF inspects some small-caliber battle damage dealt to his 1-16 during a stiff engagement with German aircraft in the fall of 1941. (Photo: Russian Aviation Research Trust.)

A fighter pilot of 13 IAP/VVS-KBF inspects some small-caliber battle damage dealt to his 1-16 during a stiff engagement with German aircraft in the fall of 1941. (Photo: Russian Aviation Research Trust.)

combat with VVS units that included 88 IAP. Among the Soviet pilots shot down was six-victory ace Leytenant Vasiliy Knyazev, who was fortunate to survive. On August 31, in the same area, Il./JG 3’s Oberfeldwebel Heinrich Brenner claimed a DB-3, followed by a “V-l 1” (probably an 11-2 of 210 ShAP). That day, also, the pilots of I1./JG 3 destroyed six Soviet aircraft in the air over the Kremenchug sector, including a TB-3 heavy bomber of 14 ТВАР shot down by the unit commander, Hauptmann Gordon Gollob (his thirty-sixth victory).

combat with VVS units that included 88 IAP. Among the Soviet pilots shot down was six-victory ace Leytenant Vasiliy Knyazev, who was fortunate to survive. On August 31, in the same area, Il./JG 3’s Oberfeldwebel Heinrich Brenner claimed a DB-3, followed by a “V-l 1” (probably an 11-2 of 210 ShAP). That day, also, the pilots of I1./JG 3 destroyed six Soviet aircraft in the air over the Kremenchug sector, including a TB-3 heavy bomber of 14 ТВАР shot down by the unit commander, Hauptmann Gordon Gollob (his thirty-sixth victory).

The l-16-equipped 69 IAP was reinforced during the Battle of Odessa by detachments from several units of VVS-ChF. including 8 IAP. This unit achieved fame throughout Soviet Union for its performance during the bitter fight for air supremacy in the late summer and autumn of 1941. This photo shows an 1-16 pilot receiving last – minute instructions from a VVS naval kapitan prior to takeoff. (Photo: Denisov.)

The l-16-equipped 69 IAP was reinforced during the Battle of Odessa by detachments from several units of VVS-ChF. including 8 IAP. This unit achieved fame throughout Soviet Union for its performance during the bitter fight for air supremacy in the late summer and autumn of 1941. This photo shows an 1-16 pilot receiving last – minute instructions from a VVS naval kapitan prior to takeoff. (Photo: Denisov.)

shot down during the Battle of Odessa22 fell victim to the fighter aces of Mayor Lev Shestakov’s 69 IAP. Lev Shestakov was credited with the destruction of eleven enemy aircraft (including eight shared victories) by mid-September 1941.

shot down during the Battle of Odessa22 fell victim to the fighter aces of Mayor Lev Shestakov’s 69 IAP. Lev Shestakov was credited with the destruction of eleven enemy aircraft (including eight shared victories) by mid-September 1941.

same area. He was in turn bounced by four Bf 109s. The Soviet pilot managed to escape in a cloudbank.

same area. He was in turn bounced by four Bf 109s. The Soviet pilot managed to escape in a cloudbank.

safe landing at Nizino. This was Brinko’s twelfth victory. ZG 26 registered three Bf 110s shot down this day.1

safe landing at Nizino. This was Brinko’s twelfth victory. ZG 26 registered three Bf 110s shot down this day.1

seventeen Soviet aircraft shot down, against three losses.4 L1I./JG 27 alone recorded nine victories, including four by Oberfeldwebel Franz Blazytko. But these successes could not outweigh the loss of one of the most outstanding pilots of this Gruppe, Leutnant Hans Richter. Having achieved his twenty-second kill, Richter was attacked from behind by an 1-16. His comrades heard his cry over the radio:

seventeen Soviet aircraft shot down, against three losses.4 L1I./JG 27 alone recorded nine victories, including four by Oberfeldwebel Franz Blazytko. But these successes could not outweigh the loss of one of the most outstanding pilots of this Gruppe, Leutnant Hans Richter. Having achieved his twenty-second kill, Richter was attacked from behind by an 1-16. His comrades heard his cry over the radio: formations of Soviet fighters. In the ensuing dogfight, the Soviet pilots claimed ten enemy aircraft shot down, " but 13 OIAE/KBF lost two pilots killed and one wounded. Soviet antiaircraft batteries claimed another five German planes destroyed, but German loss statistics note that six Luftflotte I aircraft were shot down on September 23, 1941—two Ju 87s, two Ju 88s, one Bf 109, and one Bf 110. On the other hand, JG 54 reported seventeen victories this day.

formations of Soviet fighters. In the ensuing dogfight, the Soviet pilots claimed ten enemy aircraft shot down, " but 13 OIAE/KBF lost two pilots killed and one wounded. Soviet antiaircraft batteries claimed another five German planes destroyed, but German loss statistics note that six Luftflotte I aircraft were shot down on September 23, 1941—two Ju 87s, two Ju 88s, one Bf 109, and one Bf 110. On the other hand, JG 54 reported seventeen victories this day.

25 to September 28. Hauptmann Ernst Kupfer, of I./StG 2, displayed an almost fanatical determination to destroy the Soviet naval vessels during these final raids. After Kupfer scored a hit on a cruiser on September 28, his Ju 87 was attacked by Soviet fighters. His airplane was badly shot up and he made a forced landing at the fighter airfield at Krasnogvardeisk. A few hours later,

25 to September 28. Hauptmann Ernst Kupfer, of I./StG 2, displayed an almost fanatical determination to destroy the Soviet naval vessels during these final raids. After Kupfer scored a hit on a cruiser on September 28, his Ju 87 was attacked by Soviet fighters. His airplane was badly shot up and he made a forced landing at the fighter airfield at Krasnogvardeisk. A few hours later,

Philipp and Spate stood at the peak, closely followed by Leutnant Josef Pohs, who had forty-three, and Hauptmann Franz Eckerle, Oberleutnant Max-Hellmuth Ostermann, and Oberleutnant Hans-Ekkehard Bob, each with thirty-seven.

Philipp and Spate stood at the peak, closely followed by Leutnant Josef Pohs, who had forty-three, and Hauptmann Franz Eckerle, Oberleutnant Max-Hellmuth Ostermann, and Oberleutnant Hans-Ekkehard Bob, each with thirty-seven. on the highway to Moscow to attack to the north and south of Smolensk, aiming at the city of Vyazma, in the hope of surrounding the entire Soviet Western Front. At the same time, Generaloberst Heinz Guderian’s Panzergruppe 2 was to strike from the Konotop-Romny sector, in the south, and advance in a northeasterly direction. The aim of this operation was to envelop General-Leytenant Andrey Yeremenko’s Bryansk Front, which had been severely crippled by Guderian’s troops in the Battle of Kiev.

on the highway to Moscow to attack to the north and south of Smolensk, aiming at the city of Vyazma, in the hope of surrounding the entire Soviet Western Front. At the same time, Generaloberst Heinz Guderian’s Panzergruppe 2 was to strike from the Konotop-Romny sector, in the south, and advance in a northeasterly direction. The aim of this operation was to envelop General-Leytenant Andrey Yeremenko’s Bryansk Front, which had been severely crippled by Guderian’s troops in the Battle of Kiev.

Hurricane and roughly equivalent to the Bf I09E, it proved inferior to the Bf 109F. Not least due ro frustrating technical and logistical problems, the equip

Hurricane and roughly equivalent to the Bf I09E, it proved inferior to the Bf 109F. Not least due ro frustrating technical and logistical problems, the equip

On one occasion, ten of Ill./JG 52’s Bf 109s caught a squadron of 1-153 fighter-bombers and blew all but one of the Soviets out of the sky. The 1-153 that was left from this carnage managed to get off only due to the supreme flying skills of its pilot. Even if no corresponding Soviet accounts have been found, it is possible that

On one occasion, ten of Ill./JG 52’s Bf 109s caught a squadron of 1-153 fighter-bombers and blew all but one of the Soviets out of the sky. The 1-153 that was left from this carnage managed to get off only due to the supreme flying skills of its pilot. Even if no corresponding Soviet accounts have been found, it is possible that

their frail and slow 1-153s did not allow them to meet the enemy fighters on equal terms.

their frail and slow 1-153s did not allow them to meet the enemy fighters on equal terms.

UnterofRzier Alfred Grislawski (r.), shown next to his Bf 109F, Yellow 9, was one of the up and coming aces of 9,/JG 52 who roamed the skies over the Ukraine in the fall of 1941. Grislawski, the son of a miner, is regarded as one of the toughest fighter pilots of the Luftwaffe. During most of his missions in 1941 he flew as the wingman of the famous Leutnant Hermann Graf. Grislawski would survive the war with a total of 133 victories. (Photo: Grislawski.)

UnterofRzier Alfred Grislawski (r.), shown next to his Bf 109F, Yellow 9, was one of the up and coming aces of 9,/JG 52 who roamed the skies over the Ukraine in the fall of 1941. Grislawski, the son of a miner, is regarded as one of the toughest fighter pilots of the Luftwaffe. During most of his missions in 1941 he flew as the wingman of the famous Leutnant Hermann Graf. Grislawski would survive the war with a total of 133 victories. (Photo: Grislawski.)