Douglas DC-7

After what must have seemed like badgering by Americans indomitable C. R. Smith, Douglas finally relented after reviewing operating cost benefits, and designed and built the DC-7. Adding another 40 inches to the DC-6B fuselage, the DC-7 really was not a completely new airplane. Much of the aircrafts structure and internal systems closely matched the DC-6B, which had tremendous advantages in terms of crew familiarity and training. However, with the addition of the R-3350 Turbo Compound engines, the airplane had 20-percent more power available than the R-2800- equipped DC-6B, and yet fuel consumption remained the same. More passengers per flight now meant that all these new features gave the airlines a nice, theoretical improvement in their bottom line.

The DC-7s entered revenue service on November 12, 1953. This latest Douglas airliner was also a fast airplane, eclipsing the Connie’s cruise speed by some 30-plus mph. Its faster speed was critical in making the FAA flight-time requirement of less than eight scheduled hours for the flight crew, and after only a few short weeks of being the transcon champ, TWA’s dominance fell to American Airlines.

From a “what’s new” standpoint, the DC-7 series introduced the use of titanium in commercial airliners.

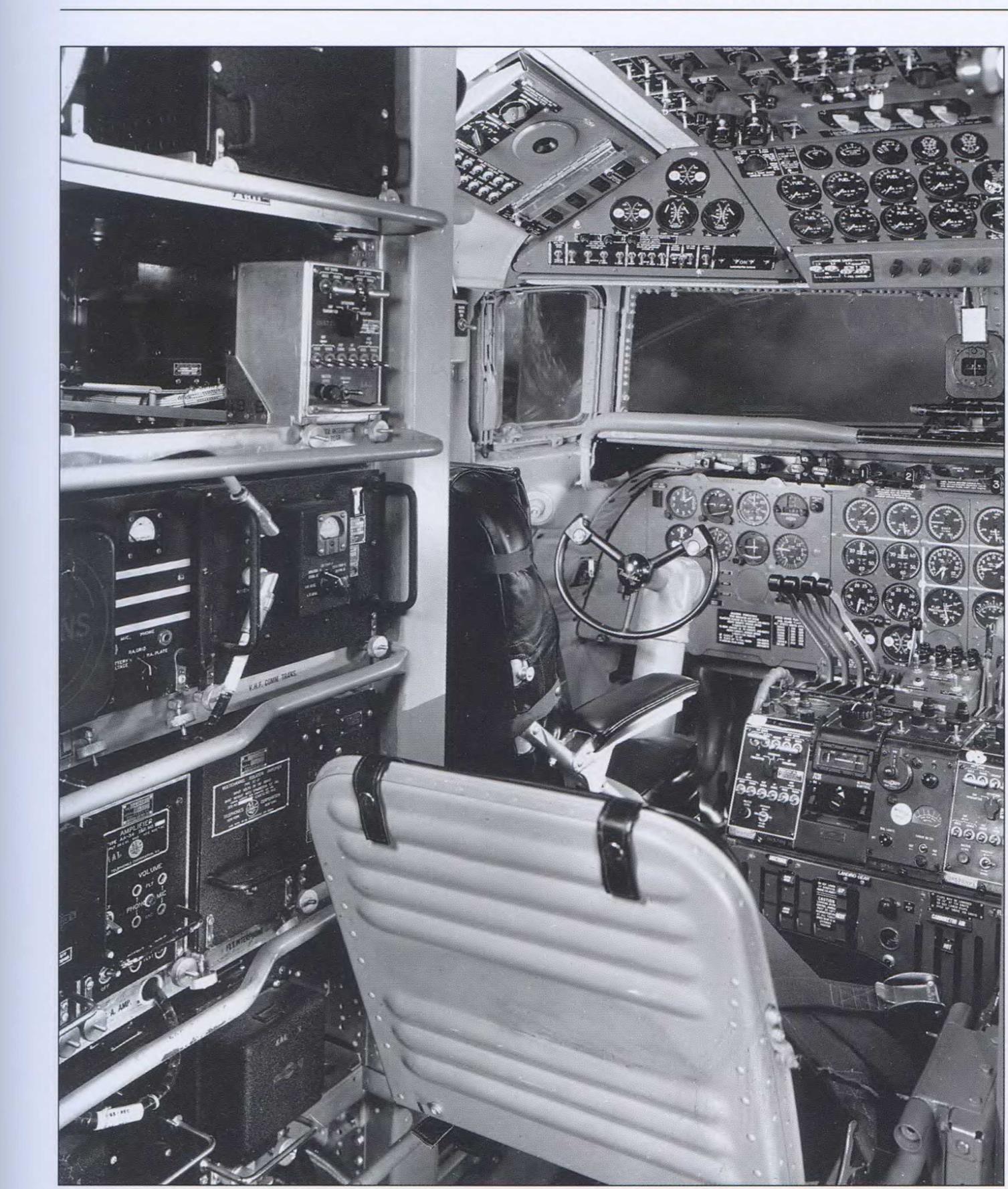

Cockpit of the DC-7 shows a well-laid-out instrument panel and control pedestal with the throttles, radio consoles, and trim wheel readily at hand. Flight Engineer’s seat is facing forward in this photo giving him access to the control pedestal and the overhead panel controlling the aircraft’s many onboard systems. Radio rack at left provided easy access for avionics maintenance personnel who may have had to change an entire radio unit or repair one of the many vacuum tubes contained therein. (Mike Machat Collection)

Cockpit of the DC-7 shows a well-laid-out instrument panel and control pedestal with the throttles, radio consoles, and trim wheel readily at hand. Flight Engineer’s seat is facing forward in this photo giving him access to the control pedestal and the overhead panel controlling the aircraft’s many onboard systems. Radio rack at left provided easy access for avionics maintenance personnel who may have had to change an entire radio unit or repair one of the many vacuum tubes contained therein. (Mike Machat Collection)

The landing gear doors were milled from this exotic and lightweight metal, thus reducing their weight by some 44 percent. Also novel on the aircraft was the enginecooling ducting, which operated alternately during icing conditions. One other innovative feature of this fast airplane was the ability to place only its main landing gear in a down-and-locked position during rapid descents, thereby acting as speed brakes. We can only wonder how many false reports of ccfailed nose gear extension” observant pilots of other aircraft called in to the tower!

As we look back on the 1953 to 1954 period it seems as if Douglas had finally wrestled the fleeting lead from Lockheed in providing the next level of air service to the airlines and the public. However, as we all know, competition in the airline and airframe business can oftentimes be quite cutthroat, and can change dramatically at a moment’s notice.