WELCOME ABOARD THE 707

By Jon Proctor

|

A |

s with the Lockheed Electra, early 707 operations utilized boarding steps rather than jet – ways—those covered bridges that are today’s norm. Using this conventional form of embarking on one’s first jet flight, unless the weather was bad, provided an exciting preview. You could not help but be awestruck by the sheer size of this new behemoth.

The use of separate aircraft doors for first-class and coach passengers was a short-lived phenomenon, done away with when space constraints dictated nose-in parking and single-point boarding. Status – minded customers soon learned that you could board through the first-class entryway by waiting until the last minute because the aft coach door was closed first, in order to facilitate engine start-up.

As a teenager, my only thought was to board my first jet flight as soon as possible, on a TWA 707, from Chicago to Los Angeles in September 1959. Thanks to the generosity of my brother, I had the extra $7 to purchase a “jet surcharge” coupon necessary to upgrade from a Super-G Constellation flight, and was eager to find a good seat. On early jet flights, coach seat assignments were not available on “through” trips, and TWA Flight 29 had originated in Pittsburgh.

Perhaps it was my imagination, but the air conditioning seemed better on this jet than on an older DC-7, as the cool air hit my face as soon as I entered the airplane. Walking forward toward seat 18A, I immediately noticed the PSUs, or passenger service units, that hung from the open, overhead racks. Each unit contained a “Fasten Seat Belt” and “No Smoking” sign,

|

Passengers board an American Airlines Boeing 707 Flagship New Jersey at Los Angeles International in the transitional days before fully enclosed jet bridges attached directly to new satellite terminal buildings to keep passengers protected from the elements. (Craig Kodera Collection) |

three air vents, individual reading lights, and a small speaker to pipe boarding music through the cabin. There was plenty of legroom on this airplane, even in coach. Each row enjoyed two of the smaller windows, and the seats were deep and comfortable.

Instead of plug-in tray tables, each seatback included a drop-down tray. The traditional propliner window curtains were replaced by window shades that could be pulled up or down. Side lighting came from a panel that ran the length of the cabin on either side, just above the windows. In the ceiling above the aisle were circular fixtures that seemed to serve no purpose on this daylight flight. Later, I learned that these “domes” contained lighting that could be adjusted from “bright” to “night,” and were designed to replicate portholes in the aircraft ceiling. The night setting featured pinholes of light against a dark background, giving the impression of a planetarium filled with stars.

The air conditioning produced a constant hum as boarding was completed. Together with the airplane’s soundproofing it was sufficient to mask any engine noise, and I suddenly became aware that the airplane was moving, backward. It was my first time experiencing pushback from a gate with a tug attached to the nose gear. The first hint of engine noise came as we taxied away from the gate to the runway.

The 707 seemed to taxi as a stable platform, rather than the subtle bouncing I remembered from

piston-powered airliners; it moved rock-solid as we taxied along. Although there was no prop-era engine run-up, the Boeing was eased onto the runway, aligned for takeoff, and then stopped. Now the engine noise level rose to a rumble, gaining power. Finally, the brakes were released and we slowly lumbered down the runway, gradually increasing speed. After what seemed like an eternity, the front of the cabin rose and our jet broke ground with a bit of a thump as the main landing gear rotated before retracting into the fuselage. The engine noise subsided a bit, no longer bouncing off the tarmac, as the ground fell away.

“Yankee Pot Roast,” served for lunch, was the first truly hot meal I could remember on an airplane, with an accompanying beverage in a real glass. There were no carts in the aisles to block access to the three aft lavatories that featured flush toilets, another first.

The aft cabin noise level could not truly be described as quiet but in marked contrast to a propliner it was all but vibration free. Less than four hours later, TWA Flight 29 landed at Los Angeles International Airport, more than two hours sooner than I would have arrived on the Super-G Constellation on which I had originally booked space. But the thrill of an early jet came at a price. I never did get to fly on a Super-G.

This work by famed artist Ren Wicks depicts the dome lighting of TWA’s 707s, designed to look like portholes in the aircraft ceiling. At night, pinholes of light against a dark background gave the impression of a night sky filled with a galaxy of stars. (TWA/Jon Proctor Collection)

This work by famed artist Ren Wicks depicts the dome lighting of TWA’s 707s, designed to look like portholes in the aircraft ceiling. At night, pinholes of light against a dark background gave the impression of a night sky filled with a galaxy of stars. (TWA/Jon Proctor Collection)

|

|

The unique 707-200 series, built at the request of Braniff International, combined the Model 100 fuselage with more-powerful JT4A-3 engines used by the -300 model. Only five examples were built, including one that was lost in a pre-delivery demonstration and acceptance flight accident. (Boeing/Jon Proctor Collection)

|

|

The first 707-138 for Qantas sits on the ramp at Boeing’s Renton plant shortly after rollout. Boeing engineers removed 10 feet from the 707-120 fuselage design, aft of the wing, to bring about the "short-body" 707-138; Qantas was the only customer. In the background new 707 jets for TWA, American, and Continental receive finishing touches before their first flights. (Qantas)

certificate, nor did it attract additional customers. Qantas placed the type into service on July 29, 1959, on the multi-stop route between Sydney and San Francisco.

Boeing’s intercontinental 707-320 was first delivered to launch customer Pan Am in July 1959, and was specifically engineered for transoceanic flights with increased passenger and cargo capacity. Its fuselage was stretched 8 feet 5 inches, bringing the maximum passenger load to 189. A 21,200-gallon boost in fuel capacity came from a center fuselage tank and additional tankage in the wings, increasing the -320’s range to 4,360 miles.

The -320 wing also featured an enlarge planform with a 12-foot increase in span, a new leading-edge airfoil at the wing root, and increased area of the inboard trailing – edge flaps as well. The same JT4A-3 engine assigned to the 707-200 powered the intercontinental version, and a total of 69 were built for Air France, Pan Am, Sabena, and TWA.

An otherwise carbon copy of the -320, the 707-420, was equipped with Rolls-Royce Conway 50B bypass engines. A total of 37 were sold to eight overseas carriers, the first being, quite appropriately, BOAC.

|

|

|

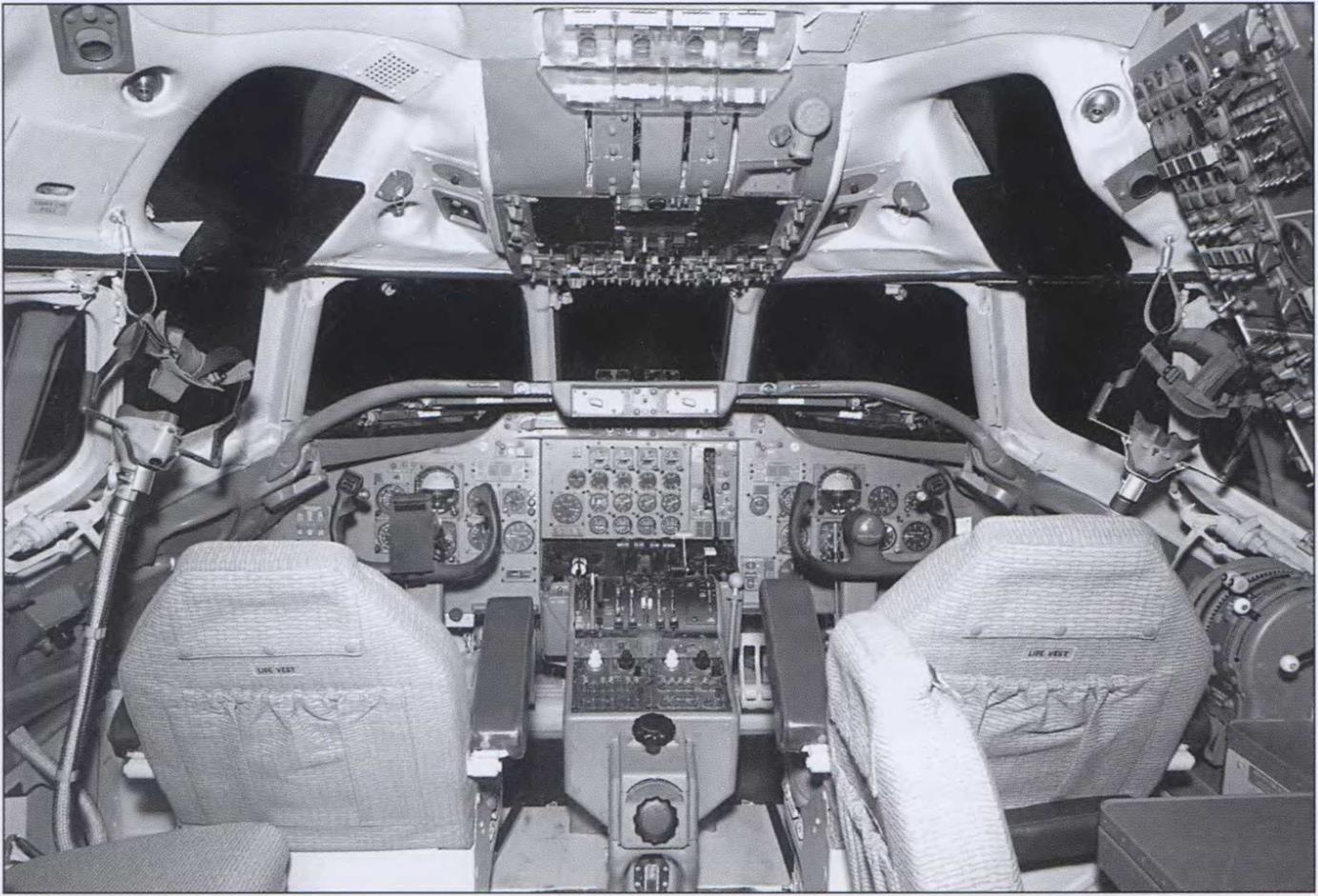

The DC-8’s cockpit was much roomier and offered much greater outward visibility than that of its piston-powered predecessors. Flight Engineer’s station is visible to the right with an observer’s jump seat at extreme left. Note move – able sunshades mounted on a circular track to ensure placement anywhere they were needed, a unique Douglas feature. Emergency quick – donning oxygen masks seen hanging next to each seat were a new addition for the flight crew. (Mike Machat Collection)

The DC-8’s cockpit was much roomier and offered much greater outward visibility than that of its piston-powered predecessors. Flight Engineer’s station is visible to the right with an observer’s jump seat at extreme left. Note move – able sunshades mounted on a circular track to ensure placement anywhere they were needed, a unique Douglas feature. Emergency quick – donning oxygen masks seen hanging next to each seat were a new addition for the flight crew. (Mike Machat Collection)

Douglas DC-8-10/20/30/40

Trailing the 707’s entry into service by nearly a year, the first Douglas DC-8 was delivered to launch customer United Air Lines on June 3, 1959. Powered by the same Pratt & Whitney JT3C-6 engines mounted on Boeing’s 707-120, the DC-8-10 featured a heavier, 265,000-pound maximum takeoff weight and a substantially greater range of up to 3,900 miles. At just over 146 feet in length, it was 2 feet longer than the 707-120, with a maximum density listed at 176 passengers.

Delta Air Lines accepted its first DC-8-10 on July

21 and wasted no time showing it off to the public; a day later it set a 1-hour 21-minute speed record between Miami and Atlanta. A second DC-8 was accepted on September 14.

Both carriers began DC-8 revenue flights on September 18, 1959, with Delta beating United into actual service entry by virtue of their time zones. Its Flight 823 departed for Atlanta from New York-Idlewild at 9:20 AM Eastern time, while United’s Flight 800 left San Francisco at 8:30 AM for New York, but in the Pacific time zone.

|