Both OST and those dealing with space issues in OMB had recognized at the start of 1971 that a decision on whether or not to proceed with NASA’s space shuttle program would almost certainly be made during the consideration of NASA FY1973 budget request that fall. The two organizations decided that it would be useful to have an external group assess the technical aspects of the NASA shuttle concept and the shuttle’s relationship to likely future space program activities. The Mathematica study was already underway to assess shuttle economics; there was a felt need for a parallel technical assessment by an expert group outside the government. To take on this task, science adviser David decided to constitute a “special panel” of the President’s Science Advisory Committee (PSAC).

David discussed a potential chair for the panel with George Low in April. David’s first inclination was to have Gene Fubini be the chairman. Fubini was a well-known “gadfly” in the Washington technical community, respected for his technical acumen and insight, but notorious for his arrogance and quick temper. Low suggested that “Fubini would not be the right person because

(a) he is too flighty and jumps too much from one thought to another, and

(b) he really does not have any aircraft background to contribute to this.” Low suggested several alternatives among the respected leaders of the aerospace community. Low soon learned that David had selected one of his suggested people, Alexander Flax, as chair; Flax was head of the national security think tank Institute for Defense Analysis and from 1965 to 1969 had been Assistant Secretary of the Air Force for research and development and simultaneously director of the National Reconnaissance Office. Low observed that “Ed David really wants to be helpful in establishing this panel.”11

Fubini was made a member of what quickly came to be known as the “Flax committee.” Other members of the group included both individuals with the aerospace engineering background needed to assess shuttle design and potential users of the shuttle’s capabilities. The Flax committee scheduled its first meeting for August 13-15 at the National Academy of Sciences summer conference center in Woods Hole, Massachusetts. In advance of the meeting, OMB’s Don Rice sent David a list of questions that he hoped the Flax committee would address. In turn, David forwarded the questions to NASA so that NASA was prepared to respond as they interacted with the Flax committee. Among the ten questions were: [9]

• “How sensitive are the cost benefit relationships to changes in the rate of activity and assumptions about the lifetimes of unmanned satellites?”12

Also in advance of the Woods Hole meeting, Fubini met with Low. He told Low that the committee would work “under the premise that the Science Adviser cannot recommend to the President the cancellation of the United States manned space flight program”; the group should thus ask “what is the manned space flight program that (a) is acceptable from a budget point of view; (b) is clearly a step beyond what has already been achieved; and (c) is not dead-ended?”13

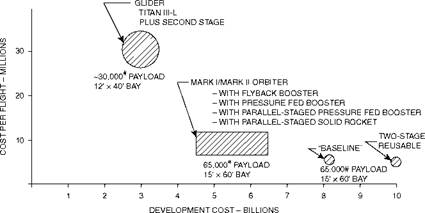

After the first Flax committee meeting, Dale Myers reported that in synthesizing his committee’s initial reactions Flax had suggested that the committee “felt that . . . the broad implications of the shuttle had not yet been addressed.” The committee thought that “the peak funding and perhaps the total funding” for the shuttle program were too expensive to be acceptable and that “the program goes on too long before there is a payoff.” (At this point, NASA was still advocating in its external presentations the two-stage, fully-reusable shuttle design.) Flax had added that the committee’s view was that “a smaller, lighter, shuttle vehicle seemed to be in order” and that the “60 x 15 payload compartment may be larger than we need.” With respect to the reactions of other committee members, Myers observed that “Fubini felt that a program this long should have something spectacular every four years.” Committee member Richard Garwin from IBM “felt that there should be more effort on big, dumb boosters, parachute recovered boosters, automatic landing, unmanned flights of the shuttle, and much greater use of the data relay satellites where you can get rid of the men in the orbiter. . . All actions done by men in orbit can be done by men on the ground using a data relay satellite and good data transmission.” Myers said that “most of the other members of the Committee were not very outspoken.” Myers paraphrased the committee’s questions:

1. “Will the users really design cheaper payloads to take advantage of the volume and weight capability?”

2. “Will the launch rate stay at 40/year or greater during an era when satellite life is increasing?”

3. “Is there a firm requirement for a 15 x 60 payload compartment?”

4. “Why crossrange?”

5. “Why not build the booster first?” and

6. “Why not unmanned shuttles, with automatic landings, or parachutes?”14

Low met with David on August 24 to discuss the results of the committee meeting. It was David’s feeling “that the Flax Committee (with Fubini leading the pack) is going to come in with some interesting options” that “include a shuttle of about $5 billion total investment running about $1 billion per year.” Low told David that NASA “was thinking along similar lines but so far had not discussed them in any detail with the Flax Committee.”15 These budget targets, no more than $1 billion per year and a total investment cost for shuttle development of $5 billion, were by the end of August beginning to be recognized by NASA as defining the limits within which a proposal for presidential approval of the shuttle had the best chance of success. The question facing Fletcher, Low, and their engineering colleagues was whether a shuttle worth having, particularly one that met both NASA’s institutional needs and the requirements set out by the national security community, could be developed within those budget constraints. It was clear that the reusable two-stage shuttle, with development cost estimates of $10 billion or more, could not be pursued on a $1 billion per year budget; this had led NASA internally to abandon that option during the summer.