Ending Exploration

Richard Nixon saw in the Apollo H mission a unique opportunity. Project Apollo had been intended from its 1961 approval by President Kennedy to be a large-scale effort in “soft power,” sending a peaceful but unmistakable signal to the world that the United States, not its Cold War rival the Soviet Union, possessed preeminent technological and organizational power.11 Nixon agreed with this rationale for the lunar landing program, and in his first months as president made sure to identify himself and his foreign policy agenda with what he later would hyperbolically characterize as “the greatest week in the history of the world since the Creation.” But Nixon’s embrace of Project Apollo as a tool of American soft power was short-lived. Once the United States had won the race to the Moon, he perceived little foreign policy benefit from subsequent lunar landing missions or from approving a post-Apollo program focused on preparing for missions to Mars. Other considerations, primarily domestic in character, would determine the Nixon approach to space in the post-Apollo period.

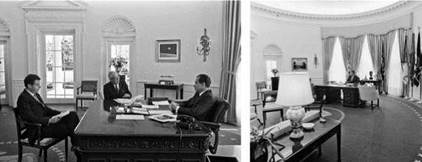

Like many other Americans, Nixon quickly lost interest in continuing Apollo flights to the Moon. As early as December 1969, after the first two lunar landings, he remarked that he “did not see the need to go to the moon six more times.” When the Apollo 12 crew visited the White House that month, mission commander Pete Conrad came away “disappointed and disillusioned.” He reported that Nixon evidenced an “apparent lack of interest in the space program.” Nixon did become emotionally engaged with the fate of the Apollo 13 crew, but that near-fatal experience only added risk avoidance to lack of interest as part of Nixon’s attitude toward lunar missions. For the Apollo 15 mission in July 1971, Nixon slept through the launch, even though the White House felt it should announce that he had followed the event closely. By that time Nixon was already urging his associates to find ways of canceling the last two Apollo missions, Apollo 16 and 17. By April 1970, the iconic “Earthrise” photograph taken during the Apollo 8 mission that had been hanging on the Oval Office wall throughout 1969 was removed, a symbolic action reflecting the president’s lack of commitment to continuing space exploration.

As Apollo 17 lifted off the lunar surface on December 14, 1972, President Nixon issued a statement saying “this may be the last time in this century that men will walk on the Moon.” As the statement was read to the Apollo 17 crew as they circled to Moon before heading back to Earth, astronaut Harrison “Jack” Schmitt was furious, thinking “that was the stupidest thing a President could have said. . . Why say that to all the young people in the world. . . It was just pure loss of will.”12 By his space decisions, Nixon made sure that his forecast would become reality. As of this writing, humans have not traveled beyond the immediate vicinity of Earth for 42 years, and no such journey is planned before 2021, almost 50 years after the last Americans left the Moon.

Nixon coupled his lack of personal interest in continuing Apollo flights to a political judgment with respect to the space program—that the American public was not interested in supporting an expensive, exploration-oriented space program. As he met with NASA Administrator Tom Paine in January 1970 to explain his decision to reject the Space Task Group-recommended post-Apollo program, Nixon told Paine “the polls and the people to whom he talked indicated to him that the mood of the people was for cuts in space.”

In May 1961, John Kennedy had paid little attention to poll results showing that the majority of the U. S. public opposed spending the sums of money needed to send Americans to the Moon; Kennedy proposed Apollo as a top-down leadership initiative based on geopolitical considerations. In

|

Richard Nixon’s interest in Apollo missions was not long-lasting. As he met in December 1969 with his assistant Peter Flanigan (at the front of Nixon’s desk) and science adviser Lee DuBridge, the famous Apollo 8 “Earthrise” photograph was hanging on the Oval Office wall. (left image) By April 1970, the photograph was gone. (right image)13 (National Archives photo WHPO 2598-15 (left) and WHPO photo 4518-6 (right), the latter courtesy of the Richard Nixon Presidential Library and Museum) |

contrast, Richard Nixon saw no persuasive foreign policy or national security reason to lead a reluctant nation and its representatives in Congress toward accepting an ambitious post-Apollo space program, particularly one aimed at developing the capabilities needed for early trips to Mars. Staff assistant Clay Thomas “Tom” Whitehead, who among the White House staff had the most level-headed approach to future space activities, commented that “no compelling reason to push space was ever presented to the White House by NASA or anyone else.”14

The immediate consequence of Richard Nixon’s decision not to continue space exploration was suspending production of the Saturn V Moon rocket and approving a NASA budget outlook that forced the agency’s leadership to cancel two planned Apollo missions in order to have funds available for future projects. During the 1960s NASA had developed the Saturn V and its related ground facilities on the expectation that the vehicle would remain in service for many years and would be the enabler of a continuing exploration- oriented space effort. These hopes were dashed by Richard Nixon’s initial space decisions; those decisions meant that the United States was voluntarily giving up for the foreseeable future the results from its multibillion dollar investment in exploratory capabilities and transforming the unused Saturn V launchers into very impressive museum exhibits.

There is one sense in which Richard Nixon’s decision to reject continued space exploration might seem somewhat surprising. Nixon often included space activity as an important aspect of his frequently repeated call for “exploring the unknown,” an activity that he believed was essential if the United States was to remain a “great nation.” For example, in February 1971 he told a group of astronauts “in the history of great nations, once a nation gives up in the competition to explore the unknown, or once it accepts a position of inferiority, it ceases to be a great nation.” In a June 1972 conversation with the Apollo 16 crew, Nixon equated exploring the unknown with concepts as varying as “science, breakthroughs in education, breakthroughs in technology, breakthroughs in transportation,” adding “space—that’s the unknown. What’s out there?”15 Nixon did communicate to his associates that he was interested in eventual human journeys to Mars, and even mused about the possibility of finding life on a moon of Jupiter, but he saw those activities in the far future, not as objectives related to the decisions he would make during his time in the White House. Nor did Nixon cast his decision to approve the space shuttle in the context of its being an initial step in a decades-long effort to explore destinations beyond the immediate vicinity of Earth. NASA in its input to the Space Task Group had portrayed the space shuttle as part of a coherent long-range strategy ultimately leading to outposts on the Moon and journeys to Mars, and even in 1971 retained elements of that thinking in its technical planning, but that perspective was not considered as part of Nixon’s decision to approve the shuttle.

To Nixon, “exploration” was not a sharply defined concept, and his repeated calls for “exploring the unknown” seem to have been little more than what a historian would call a “trope”—an overused rhetorical device offered in the place of substantive thought. Nixon was notoriously poor at conversation with any but those in his inner circle, and falling back on repetitive rhetoric was often his way of dealing with discussions of policy issues with those outside that inner circle. The lack of logic in Nixon’s attitude with respect to space activities was on display as he told one of his Congressional relations staff in 1971 that “the United States should not drop out of any competition in a breakthrough in knowledge—exploring the unknown. That’s one of the reasons I support the space program.” Without pausing, he then said “I don’t give a damn about space. I am not one of those space cadets.”

Exploring the space frontier was in reality not part of Richard Nixon’s strategic vision for America, and thus his repeated call for “exploring the unknown” had little connection to his actual decisions on space policy and budgets in the post-Apollo period. By rejecting the recommendations of the Space Task Group, the Nixon administration attempted to reduce U. S. space ambitions to match the budget it deemed appropriate to allocate to NASA in the post-Apollo period. However, that lowering of ambitions did not happen, either then or since. The exploratory vision still persists; a 2009 blue – ribbon review of the U. S. human space flight program concluded that “Mars is the ultimate destination for human exploration of the inner solar system” and that “human [space] exploration. . . should advance us as a civilization towards our ultimate goal: charting a path for human expansion into the solar system.” Discussing the persistence of this vision, Howard McCurdy suggests “expectations invariably fail, but the underlying vision rarely dies. Rather, people update the vision. The dream moves on.”16

One can argue that Richard Nixon made a major policy mistake in mandating that the space program should be treated as just one of many government programs competing for limited resources. Certainly the belief that this judgment was ill-conceived is the long-held position of space advocates. But it is also possible that Nixon’s decision-that U. S. space ambitions should be adjusted to the funds made available through the normal policy process-was a valid reading of public preferences, and there were no countervailing reasons for him to reject those preferences. If this is the case, then the Nixon administration in its space decisions was correctly reflecting the view of the majority of the U. S. public. There is no evidence that this situation has changed over the past 40 years; the most recent review of the U. S. space exploration program notes “lukewarm public support” for a program of human space exploration and the absence of “a committed, passionate minority large and influential enough” to provide a political basis for such a program.17

What has actually happened since Richard Nixon made his decisions to end lunar exploration, not to set a new exploratory goal, and to remove the space program’s special priority is neither reduced ambitions nor increased budgets; instead, for more than 40 years there has been a continuing mismatch between space ambitions and the resources provided to achieve them. This outcome is close to the worst possible recipe for space program success; a central part of Richard Nixon’s space heritage is thus a U. S. civilian space program continually “straining to do too much with too little"