Tom Paine Urges NASA to be "Swashbuckling"

Once Apollo H had been successful in achieving the goal of a lunar landing before the end of the 1960s, Wernher von Braun had considered his work as director of the Marshall Space Flight Center completed, and during fall 1969 expressed to George Low “a strong interest” in moving to NASA Headquarters in Washington. Von Braun was burned out from his intensive efforts in getting the Saturn V ready for Apollo missions, and he and his wife, both raised as Prussian aristocrats, were ready to leave the rather provincial Huntsville, Alabama for life in Washington. Low and NASA Administrator Paine decided not to offer von Braun a headquarters line management position, but rather to invite him to become NASA’s chief planner, supervising a “strong, but small staff,” with the goal of “putting some imagination back into the future plans of the agency.” In this role, von Braun would be both the “chief architect” of and “salesman” for the future NASA program. Von Braun indicated that he was “most interested in undertaking this assignment.” He assumed his new position on March 1, 1970.10

An early von Braun project was to organize a long-range planning conference called by Paine. The purpose of the three-day conference was “to provide a long-term context against which current decisions can be tested” by expanding on the Space Task Group (STG) recommendations, which had focused on the 1970s and 1980s, to the year 2000. Paine invited visionary futurist Arthur C. Clarke to provide the keynote address for the get-together.

Paine’s hope was that the combination of extending the time frame for consideration of space options and exposing his staff to Clarke’s often far out thinking would result in a NASA long-range plan that could capture public and political imagination.11

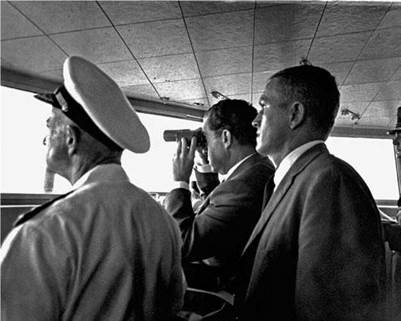

The meeting took place on June 11-14. Paine’s concluding remarks to the conference capture his exuberant personality, his fascination with things naval, and his lack of understanding, or perhaps acceptance, of the policy context in which NASA was operating in mid-1970. He urged his associates to adopt “a fighting ship analogy for the kind of society, the kind of rationale, actions, courage, and determination that we in NASA should have in the coming decades.” Paine added “we need the discipline and determination and capability of a naval fighting ship,” but that NASA should adopt a “swashbuckling, buccaneering, privateering kind of approach.” He suggested that NASA should emulate “the concept of Admiral Nelson and his band of brothers, which certainly was one of the great management teams of all times.” Paine added “we have got to enjoy the experience of living dangerously because that is really the only way to handle the kind of campaigns we are going to be waging.”12 This was certainly not the image of NASA that the White House had in mind as it tried to constrain the space agency’s ambitions. Paine’s exhortation to enjoy “living dangerously” was very likely to lead NASA, to continue the naval analogy, to crash on rocky shores.

In addition to his bullish long-range vision, Paine apparently had in his back pocket a short-term proposal for a major new initiative. Even as the STG was winding up its work the preceding September, NASA’s Milt Rosen had suggested to Paine that he should seek “a commitment to have a permanent manned space-station in earth orbit in 1976” as a means of marking the two hundredth anniversary of the Declaration of Independence. This proposal was not mentioned during the FY1971 budget discussions, as NASA fought for the program laid out in the STG report, but it was also not forgotten. In mid-June 1970, as NASA planned its FY1972 budget request, Paine was arguing within NASA that “it is extremely important that in 1976 a major mission of new significance be considered.” The leading possibility was a “first” space station that would be an advance beyond the Skylab orbital workshop, would have potential for up to ten years in orbit, and would make possible “participation by foreign astronauts or scientists.” This “’76 spectacular” would be “a source of national pride.”13

Apollo astronaut Jim Lovell called Peter Flanigan in July 1970, asking “if the Administration was looking for a space spectacular in 1976.” Flanigan told Lovell that he had once suggested a change in the NASA schedule “in order to provide a meaningful launch just prior to the 1972 election,” but that President Nixon had said that “he was not interested in this kind of grandstanding.” Flanigan told Lovell “based on this. . . the Administration was not trying to design a space spectacular for 1976.” This word may have gotten back to NASA planners; at any rate, the idea of a NASA mission tied to the country’s bicentennial was not pursued.14

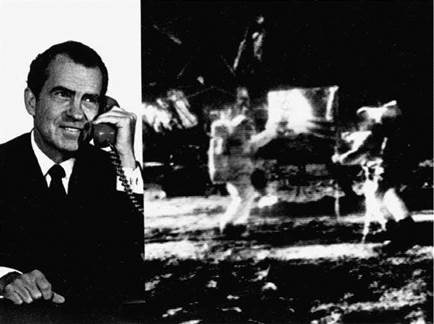

Paine in early July wrote the president, requesting an appointment to discuss the results of the long-range planning conference. Paine stressed that the purpose of the meeting “was not to discuss budgetary or detailed programming actions, or to review decisions,” but rather “to give you a heretofore unavailable Presidential level long range view of man’s future potential in space.”15 As the White House considered whether to schedule such a meeting, the first anniversary of the Apollo 11 lunar landing on July 20 passed without any major celebration. One NASA idea had been a live television conference involving President Nixon and other heads of state, with Armstrong, Aldrin, and Collins standing by. The White House did issue a presidential statement, saying “this triumph of unique achievement, described by our first man on the moon, Neil Armstrong, as ‘one small step for a man, one giant leap for mankind,’ brought with it a moment of greatness in which we all shared, a priceless moment when the people of this earth became truly one in the joy and wonder of a dream realized.”16 But there was no White House desire to stage an event intended to recapture the excitement surrounding the first lunar landing or to encourage the agency to push for the kind of future Paine had in mind.