Selecting a NASA Administrator

In 1961, a large number (anywhere from 15 to 24, according to various accounts) of individuals were considered for NASA administrator before President Kennedy and Vice President Johnson on January 30 finally settled on James Webb as their choice. Webb was one of the last Kennedy nominees for a high position. The Nixon administration also considered a (smaller) number of candidates to replace Acting Administrator Tom Paine. During the transition, the position was offered to retired Air Force general Bernard Schriever, who declined, saying “he had too many obligations” to take on a full-time administration job. The position was reportedly also offered to Simon Ramo, head of the aerospace industry firm TRW. President Nixon on January 28 personally offered the job to Patrick Haggerty, chairman of Texas Instruments. Haldeman recorded that Nixon was “very impressed by his obvious brain power, and with his concept of institutionalizing innovation.” In fact, Nixon told Haggerty that his work in this respect “maybe was a more important contribution to the nation than actual federal service.” Haggerty agreed. He wrote Nixon on February 4, saying that “your invitation to join your Administration as Director of NASA both did me a great honor and faced me with an extremely difficult decision.” However, wrote Haggerty, he had decided, as the president had suggested, that finishing his effort at Texas Instruments to institutionalize innovation took priority. He thus turned down the president’s invitation.42

Almost by default, Tom Paine thus became Richard Nixon’s choice as NASA administrator. After Haggerty turned down the job, science adviser DuBridge recommended that Paine be kept on; the space trade press noted that “more and more sentiment was growing among space insiders to keep Dr. Paine.” President Nixon himself would have preferred to offer the position to Apollo 8 commander Frank Borman, with whom he had become impressed in the first weeks of his administration. Near midnight on February 24, the second day of his initial European tour as president, Nixon, after

|

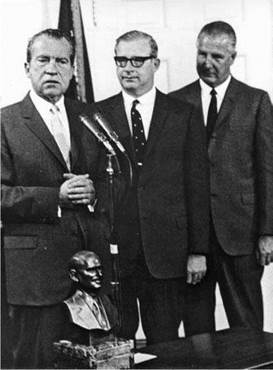

President Richard Nixon, with Vice President Spiro Agnew looking on, introduces Thomas Paine as his choice as NASA administrator on March 5, 1969. (NASA photograph GPN- 2000-001669) |

returning from dinner with Prime Minister Harold Wilson at Chequers, the prime minister’s country home, met with Haldeman in his room at the posh Claridge Hotel in London. Haldeman reported that he and Nixon, “in his pajamas and pretty well out. . . discussed the NASA appointment briefly. He said go ahead on Paine, the Deputy, unless I thought we could do Borman.” Haldeman did not think that Borman would take the job, and thus the choice of Paine as the head of NASA was made.

President Nixon announced the nomination on March 5 as he presented a trophy to the Apollo 8 astronauts at the White House, saying “there has been a great deal of interest as to who would be the new head of NASA. I will admit right now that we have searched the country to find a man who could take this program now and give it the leadership that it needs, as we move from one phase to another. This is an exciting period, and it requires the new leadership that a new man can provide.” He added “but after searching the whole country for somebody, perhaps outside the program, we found, as is often the case, that the best man in the country was in the program, and that is why I am announcing today that Dr. Paine, who is now the Acting Director of NASA, will be appointed the Director of NASA.”43

With Nixon’s choice of Paine, NASA got a leader who over the next 18 months would be an unceasing advocate for a space program more ambitious than Richard Nixon felt he could afford or that the U. S. public and the Congress would support. The gap between what Paine thought was desirable for the nation to undertake in space and what the Nixon administration decided was fiscally and programmatically possible frustrated Tom Paine, but he never lost his enthusiasm.

That NASA would indeed be frustrated in its ambitions was not clear in early 1969 as the review of options for the future in space got underway and as NASA readied itself to send Americans to the Moon. In the enthusiasm surrounding the lunar landing, it was not unreasonable for NASA to expect that the White House would want to continue the kind of ambitious space effort that had led to that remarkable achievement. With Tom Paine leading the charge, NASA set as its top priority making sure that the Space Task Group would recommend an ambitious post-Apollo effort aimed at landing on another celestial body. Having reached the Moon, the space agency now would set its sights on voyages to Mars.