I started this chapter with two beginnings. One had to do with multiplicity, indirection, and the coherence of subject positions. The other concerned the reflexive problem of the personal. Now it is possible to say that they overlap and interfere with one another.

Some observations.

I want to assert, against the purifying tropes of modernism, that whatever is personal is also social. Always. Whatever we conceal, we think is shameful, inappropriate, self-indulgent, uninteresting, whatever we conceal is also social. Elias tells us this.

It may, of course, also be shameful, inappropriate, self-indulgent, or plain, downright uninteresting at the same time as being as social.

All of these are real possibilities which we watch being performed every day. They are, indeed, performed in one way by Elias and Foucault in their writing—if only because they choose never to talk about their own “repressions,” their own subjectivities. But if we assume, as I have in this chapter, that narratives perform subject positions and object positions, then there is, at least in principle, the possibility that subject positions, those positions that constitute us as knowing subjects, are relevant if we want to understand the performativity of narratives, to understand how distributions are being made, if we want to understand what is being said and what is not.

So that is a first possibility. There is continuity between subjects Subjects 61

and objects, and we are lodged in, made by multiple and overlapping distributions, which shuffle that which is made ‘‘personal’’ and that which is rendered ‘‘eternal’’ into two heaps. And that process of shuffling is worthy of deconstructing in a contemporary version of the vanitas because it performs obviousnesses. And in particular because it performs obviousnesses.

This is where, having journeyed almost all the way with the semiotics of Michel Foucault and Louis Althusser, I finally part company from them. This is a methodological point. For I would argue that the body is a particularly sensitive instrument in part precisely because the semiotics of subject-object relations don’t come in big blocks like ideologies, discourses, or epistemes. Let me be more cautious. They may come in big blocks in certain respects. Perhaps the conditions of possibility are, indeed, in some ways uniform, singular. But they aren’t that way all the time. For smaller blocks, narratives, semiotic logics, distributions—these are multiples that are also capable of interfering with and eroding one another. At any rate they are capable of doing so under certain circumstances, in particular places or institutions. They can produce multiplicities that do not effortlessly coalesce to make singularities. In, for instance, the practices within a building, the intertextualities that pass through the body, the heterotopic space within that makes us, interpellates us and our materials in multiple ways.32

Lighten our darkness. Deliver us this day from the obviousness of our simplicities.

This is why I am more optimistic than Louis Althusser. There is mileage to be gained by attending to interferences that make multiplicities. And it is also why the body is so important. For it is a detector, a finely tuned detector of narrative diffraction patterns. It is an exquisite and finely honed instrument that both performs and detects patterns of interference, those places where the peaks come together and there is extra light. And those, such as the place I found myself in the summer of 1989, where there is dark, where there is something wrong, where the energies cancel one another out. Where multiplicity is not reduced.

This suggests that there is a place for the body, not only as the flesh and narrative blood that walks in what we used to call ‘‘the field’’ 62 Subjects bringing back reports, reports of how it is ‘‘out there,’’ but also that

there is room for the body, for the personal, in the narratives that are later performed, that perform themselves through us as we tell of narrative diffractions and interferences. For the personal, when we come to sense it in this way, is no longer ‘‘personal.’’ It is no longer necessarily personal, however it may be constructed by the modernist – inclined heirs to the civilizing process. It may be understood and performed rather as a location, one particular location, of narrative overlap. A place of multiplicity, of patterns, of patterns of narrative interference. And of irreduction.

Whether we tell stories about ourselves as we perform our situated knowledges will depend on what we are trying to achieve and on the context in which we are seeking to achieve it. The performance of re – flexivity and diffraction does not necessarily demand the immediate visibility of a narrator. But the issues are situated, specific, rhetorical, and political in character rather than great issues of principle. For it is itself wrong, a confusion, a self-indulgence, to forget that the body is a site, an important site, where subjectivities and interpellations produce effects that are strange and beautiful—indeed sometimes terrible. And these are effects that might make a difference if were able to attend to their intertextualities.

For instance, there are moments—I lived through one that I have already described—when the possibility of performing coordination between narratives is lost and it is no longer possible to link subject positions together in this way or that, to make a single story; when it is no longer possible to create, perform, and be performed by an object that is turned into a singularity; when it is no longer possible to work, as it were, perspectivally. In such moments, the interferences and overlaps perform themselves into ‘‘a’’ subject that is broken, fragmented, and decentered; a subject that is therefore interpellated by— and interpellates—a multiplicity of different objects and thereby suddenly apprehends that the failure to center is not simply a failure but also a way of becoming sensitive to the multiplicities of the world. At that moment, failure to center is also a way of learning that objects are made, and that there are many of them. It is a way of learning that objects are decentered—aset of different object positions—and a way of attending to the indirections of interference. It is also a way of apprehending that knowing is as much about making, about ontology, about what there is, as it ever was about epistemology. Subjects 63

|

|

A final question. Could I have done all this without introducing the personal?

The answer is no. Perhaps I could have made arguments like these and told it otherwise in some version or other of the god-trick. But this is not how the method of bodily interference produced its effects. So I’ll finish with another question. If we are constituted as knowing subjects, interpellated, in ways that we do not tell, then what are we doing? What are we telling? What are we making of our objects of study? Or, perhaps better, what are they making of us?

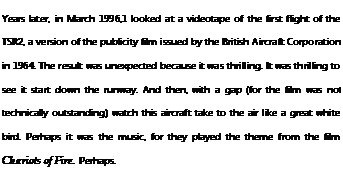

The question is real, isn’t it? At any rate it’s real from where I stand. For finally, in a study of the TSR2, it turns itself into something specific that is also not specific. If those of us who study military tech – nologies—and those who dream of them, design them, fly them—do not reflect on the aesthetics of our interpellations then we are not attending to a way of living stories that runs through us. A way of living stories that is arousing, in some ways dangerously so, that effaces the ontological in favor of the perspectival, and that makes a difference and continues to strain toward the singularities of military and technological discourse.33 This is the power of a reflexive technoscience studies: it can attend to, and learn from, dangerous arousal.

Multilingualism is not merely the property of several systems each of which would be homogeneous in itself: it is primarily the line of flight or of variation which affects each system by stopping it from being homogeneous. —Gilles Deleuze and Claire Parnet, Dialogues

So there are multiplicities. There are multiple distributions of subjects and multiple distributions of objects. And these distributions overlap. Sometimes the overlaps work to make patterns of light, somewhat singular narratives. Sometimes they consolidate themselves to make coherences, simplicities. And sometimes they do not —and then we find that we are left in the dark places, turned into a fragmented set of subject positions confronted by an equally uncoordinated set of object positions.

So there are multiplicities. There are multiple distributions of subjects and multiple distributions of objects. And these distributions overlap. Sometimes the overlaps work to make patterns of light, somewhat singular narratives. Sometimes they consolidate themselves to make coherences, simplicities. And sometimes they do not —and then we find that we are left in the dark places, turned into a fragmented set of subject positions confronted by an equally uncoordinated set of object positions.

No doubt this is uncomfortable. But, if we can work it right, perhaps in those dark moments it is easiest to learn about the making of objects and the making of subjects because in those moments it is easiest to attend to the work of distribution and coordination. And, in particular, those are the moments when it is easiest to avoid being dazzled by problems of epistemological authority and deal, instead, with ontology: with the making of what there is or there could be, with the conditions of possibility. With the performances that otherwise tend to reenact singularity. This, then, is the interest in interferences, that they allow us both to rethink and survey the character of distribution—with how it is that matters are made and arranged in the world.

In this chapter I follow Sharon Traweek and tell more stories while looking for the distributions that they make. I also follow Annemarie Mol by attending to the ways stories describe and make links: connections and disconnections or similarities and differences—that is, by attending to their interferences.11 argue that to tell stories is to perform ‘‘cultural tasks.’’ It is to distribute, to say what exists or does not. And it is to coordinate, to saywhat goes with or does not go with, what else. This means that I’m assuming, as I have above, that storytelling is performative: it makes or may make a difference in the multilingual world mentioned by Gilles Deleuze and Claire Parnet. Talk may, as it were, talk itself into being, and the stories told may shift their ma-

terial form, may perform their logic from texts or voiced words into bodies and architectures, into other forms of flesh, and into stone. So the echoes here are also with that material version of semiotics called actor-network theory and with the understandings in cultural anthropology or cultural studies of the ways in which, for instance, communities may be imagined and told into being as different stories overlap.2

![]()

![]()

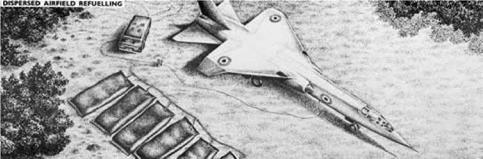

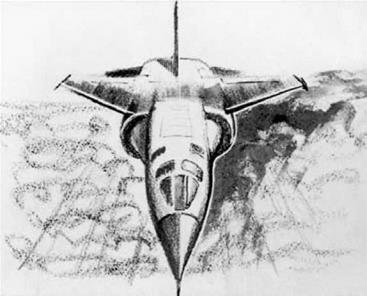

FIGURE 5.7 Trapezoidal Wings

FIGURE 5.7 Trapezoidal Wings