Perspective

|

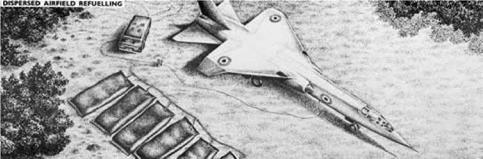

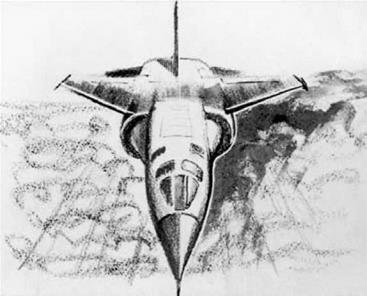

Earlier I suggested exhibit 2.1 is perspectival in character. But so too are exhibits 2.9 and 2.10. It is clear to all but the naive reader that these are pictures of the same object. In other words, we are justified in detecting the operation of yet another strategy for coordinating possibly different objects—that of perspectivalism.

I shall have more to say about this later, so let me just note for the moment that perspectivalism assumes a world that is Euclidean in character; that is, it assumes that the world is built as a threedimensional volume occupied by objects. These objects, which in – Objects 21

|

elude a variety of positions for viewing, have locations and (at any rate in the case of objects) themselves occupy three-dimensional volumes.

This is why when we look at individual perspectival drawings of the kind in exhibits 2.9 and 2.10, we tend to see a three-dimensional object, for instance an aircraft, rather than some lines on a sheet of paper. The theory of linear perspective holds that we project the lines that appear on the paper in such a drawing back into a Euclidean volume of space. That volume is occupied by a three-dimensional object that would, had it been located in such a space, have traced itself onto a two-dimensional surface in a way that corresponds with the lines on the sheet of paper. Thus in linear perspective a viewer or subject position is made that ‘‘sees’’ an ‘‘object,’’ the aircraft, even though it sees only a sheet of paper. Or, to put it differently, what is on the sheet of paper tends to produce the sense of an object because it helps to reproduce a Euclidean version of reality.

Furthermore, and an important part of this strategy, different per- spectival sketches are easily coordinated within the system. There is a formal projective geometry for saying this, but let me put it informally. One of the Euclidean assumptions of perspectivalism is that a single three-dimensional object can generate multiple two-dimen

sional perspectival depictions. Objects, the same objects, simply look different if we look at them from different standpoints. And this is what is happening here. The coordinating assumption is that there is an aircraft, the TSR2, and that it is fixed in shape. That singular fixity will generate all sorts of possible two-dimensional perspectival configurations. So long as the depictions conform to these configurations and do not demand an impossible three-dimensional object, then we tend to see the same three-dimensional object when we look at different perspectival drawings, as we do here.