The Flight Research Program

During the ten years of flight operations, five major aircraft were involved in the X-15 flight research program. The three X-15s were designated X-15-1 (56-6670), X-15-2 (56-6671), and X-15-3 (56-6672). Early in the test program the first two X-15s were essentially identical in configuration; the third aircraft was completed with different electronic and flight control systems. When the second aircraft was extensively modified after an accident midway through the test program, it became the X-15A-2. The two carrier aircraft were an NB-52A (52-003) and an NB-52B (52-008); they were essentially interchangeable.

The program used a three-part designation for each flight. The first number represented the specific X-15; 1 was for X-15-1, etc. No differentiation was made between the original X-15-2 and the modified X-15A-2. The second position was the flight number for that specific X-15. This included free-flights only, not captive-carries or aborts; the first flight was 1, the second 2, etc. If the flight was a scheduled captive-carry, the second position in the designation was replaced with a C; if it was an aborted free-flight attempt, it was replaced with an A. The third position was the total number of times any X-15 had been carried aloft by either NB-52. This

number incremented for each captive-carry, abort, and actual release. The 24 May 1960 letter from FRC Director Paul Bikle establishing this system is included as an appendix to this monograph.

Initial Flight Tests

The X-15-1 arrived at the Air Force Flight Test Center at Edwards AFB, California, on 17 October 1958; trucked over the hills from the North American plant in Los Angeles for testing at the NASA High-Speed Flight Station. It was joined by the second airplane in April 1959; the third would arrive later. In contrast to the relative secrecy that had attended flight tests with the XS-1 (X-l) a decade before, the X-15 program offered the spectacle of pure theater.1

As part of the X-15’s contractor program, North American had to demonstrate each aircraft’s general airworthiness during flights above Mach 2 before delivering it to the Air Force, which would then tum it over to NASA. Anything beyond Mach 3 was considered a part of the government’s research obligation. The contractor program would last approximately two years, from mid – 1959 through mid-1960.

Two different mission profiles were flown— one for maximum speed; and one for maximum altitude.

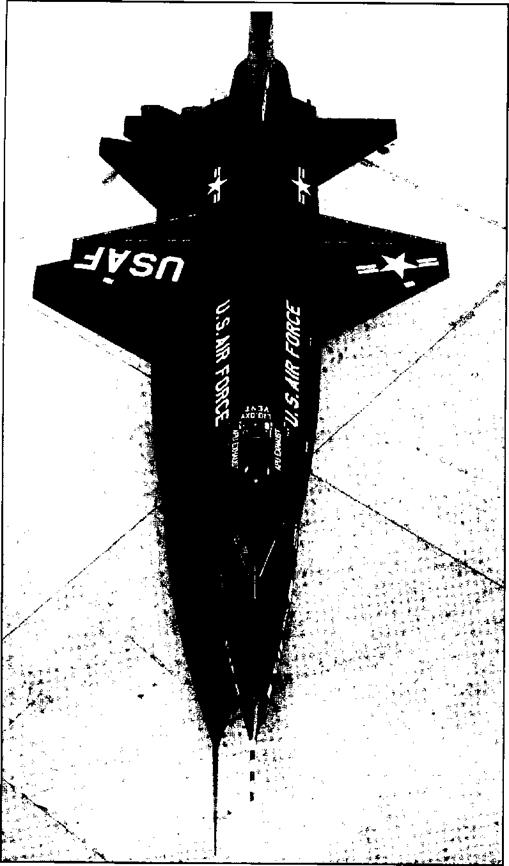

(NASA)

(NASA)

The first X-15 (56-6670) immediately prior to the official rollout ceremonies at North American’s Los Angeles plant on 15 October 1958. The small size of the trapezoid-shaped wings and the extreme wedge section of the vertical stabilizer are noteworthy. (North American Aviation)

The first X-15 (56-6670) immediately prior to the official rollout ceremonies at North American’s Los Angeles plant on 15 October 1958. The small size of the trapezoid-shaped wings and the extreme wedge section of the vertical stabilizer are noteworthy. (North American Aviation)

The task of flying the X-15 during the contractor program rested in the capable hands of Scott Crossfield. After various ground checks, the X-15-1 was mated to the NB-52A, then more ground tests were conducted. On 10 March 1959, the pair made a scheduled captive-carry flight (program flight number 1-C-l). They had a gross takeoff weight of 258,000 pounds, lifting off at 168 knots after a ground roll of 6,200 feet. During the 1 hour and 8 minute flight it was found that the NB-52 was an excellent carrier for the X-15, as had been expected from numerous wind tunnel and simulator tests. During the captive flight the X-15 flight controls were exercised and airspeed data from the flight test boom on the nose was obtained in order to calibrate the instrumentation. The penalties imposed by the X-15 on the NB-52 flight characteristics was found to be minimal in the gear-up configuration. The mated pair was flown up to Mach 0.83 at 45,000 feet.2

The next step was to release the X-15 from the NB-52 in order to ascertain its gliding and landing characteristics. The first glide flight was scheduled for 1 April 1959, but was aborted when the X-15 radio failed. The

pair spent 1 hour and 45 minutes airborne conducting further tests in the mated configuration. A second attempt was aborted on 10 April 1959 by a combination of radio failure and APU problems. Yet a third attempt was aborted on 21 May 1959 when the X-15’s stability augmentation system failed, and a bearing in the No. 1 APU overheated after approximately 29 minutes of operation.

The problems with the APU were the most disturbing. Various valve malfunctions, leaks, and several APU speed-control problems were encountered during these three flights, all of which would have been unacceptable during research flights. Tests conducted on the APU revealed that extremely high surge pressures were occurring at the pressure relief valve (actually a blow-out plug) during initial peroxide tank pressurization. The installation of an orifice in the helium pressurization line immediately downstream of the shut-off valve reduced the surges to acceptable levels. Other problems were found to be unique to the captive-carry flights and the long-run times being imposed on the APUs; they were deemed to be of little consequence to the flight test program

Long before the NB-52 first carried the X-15 into the air, engineers had tested the separation characteristics in the wind tunnels at Langley and Ames. Here an X-15 model drops – away from a model of the NB-52. Note that the X-15 is mounted on the wrong wing. This was necessary because the viewing area of the wind tunnel was on the left side of the aircraft.

(NASA photo EL-1996-00114)

(NASA photo EL-1996-00114)

since the operating scenario would be different. The APUs underwent a constant set of minor improvements early in the flight test program, but nevertheless continued to be a source of irritation until the end.

On 22 May the first ground run of the interim XLR11 engine installation was accomplished using the X-15-2. Scott Crossfield was in the cockpit, and the test was considered successful, clearing the way for the eventual first powered flight; if the first X-15 could ever make its scheduled glide flight.

Another attempt at the glide flight was made on 5 June 1959 but was aborted even before the NB-52 left the ground3 when Crossfield reported smoke in the X-15-1 cockpit. Investigation showed that a cockpit ventilation fan motor had overheated.

Finally, at 08:38 on 8 June 1959, Scott Crossfield separated the X-15-1 from the NB-52A at Mach 0.79 and 37,500 feet. Just prior to launch the pitch damper failed, but Crossfield elected to proceed with the flight, and switched the SAS pitch channel to standby. At launch, the X-15 separated cleanly and Crossfield rolled to the right with a bank

angle of about 30 degrees. The X-15 touched down on the dry lake at Edwards 4 minutes and 56 seconds later. Just prior to landing, the X-15 began a series of increasingly wild pitching motions; mostly as a result of Crossfteld’s instinctive corrective action, the airplane landed safely. Landing speed was 150 knots, and the X-15 rolled-out 3,900 feet while turning very slightly to the right. North American subsequently modified the control system boost to increase the control rate response, effectively solving the problem.

Although the impact at landing was not considered to be particularly hard, later inspection revealed that bell cranks in both main landing skids had bent slightly. The main skids were not instrumented on this flight, so no specific impact data could be ascertained, but it was generally believed that the shock struts had bottomed and remained bottomed as a result of higher than predicted landing loads. As a precaution against the main skid problem occurring again, the metering characteristics of the shock struts were improved, and lakebed drop tests at higher than previous loads were made with the landing gear test trailer that had been used to qualify the landing gear design. All other airplane sys-

North American test pilot A. Scott Crossfield was responsible for demonstrating that the X-15 was airworthy.

North American test pilot A. Scott Crossfield was responsible for demonstrating that the X-15 was airworthy.

His decision to leave NACA and join North American effectively locked him out of the high-speed and high – altitude test flights later in the program. (NASA photo EC-570-1

terns operated satisfactorily, clearing the way for the first powered flight.4

In preparation for the first powered flight, the X-15-2 was taken for a captive-carry flight with full propellant tanks on 24 July 1959. During August and early September, several attempts to make the first powered flight were cancelled before leaving the ground due to leaks in the APU peroxide system and hydraulic leaks. There were also several failures of propellant tank pressure regulators. Engineers and technicians worked to eliminate these problems, all of which were irritating, but none of which was considered critical.

The first powered flight was made by X-15-2 on 17 September 1959. The aircraft was released from the NB-52A at 08:08 in the morning while flying at Mach 0.80 and 37,600 feet. Crossfield piloted the X-15-2 to Mach 2.11 and 52,341 feet during 224.3 seconds of powered flight using the two XLR11 engines. He landed on the dry lakebed at Edwards 9 minutes and 11 seconds after launch. Following the landing, a fire was noticed in the area around the ventral stabilizer, and was quickly extinguished by ground

crews. A subsequent investigation revealed that the upper XLR11 fuel pump diffuser case had cracked after engine shutdown and had sprayed fuel throughout the engine compartment. Fuel collected in the ventral stabilizer and was ignited by unknown causes during landing. No appreciable damage was done, and the aircraft was quickly repaired.5

The third flight of X-15-2 took place on 5 November 1959 when the X-15 was dropped from the NB-52A at Mach 0.82 and 44,000 feet. During the engine start sequence, one chamber in the lower engine exploded. There was external damage around the engine and base plate, plus quite a bit of damage internal to the engine compartment. The resulting fire convinced Crossfield to make an emergency landing at Rosamond Dry Lake; he quickly shut off the engines, dumped the remaining fuel, and jettisoned the ventral6 rudder. Even so, within the 13.9 seconds of powered flight, the X-15 managed to accelerate to Mach 1. The aircraft touched down near the center of the lake at approximately 150 knots and an 11 degrees angle of attack. When the nose gear bottomed out, the fuselage literally broke in half at station’ 226.8, with about 70 percent of the bolts at the manufacturing

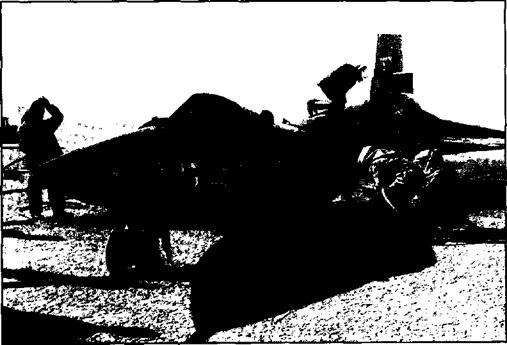

Any landing you can walk away from…

The X-15-2 made a hard landing on 5 November 1959, breaking its back as the nose settled on the lakebed. The damage looked worse than it was, and the aircraft was back in the air three months later. (NASA photo E-9543)

The X-15-2 made a hard landing on 5 November 1959, breaking its back as the nose settled on the lakebed. The damage looked worse than it was, and the aircraft was back in the air three months later. (NASA photo E-9543)

joint being sheared out. The fuselage contacted the ground and was dragged for approximately 1,500 feet. Crossfield later stated that the damage was the result of a defect that should have broken on the first flight.8 The aircraft was sent to the North American plant for repairs, and was subsequently returned to Edwards in time for its fourth flight on 11 February I960.9

The X-15-1 made its first powered flight, using two XLRlls, on 23 January 1960. This was also the first flight using the stable platform, and the performance of the system was considered encouraging. Under the terms of the contract, the X-15 had still “belonged” to North American until they had demonstrated its basic airworthiness and operation. Following this flight, a pre-delivery inspection was accomplished, and on 3 February 1960 the airplane was formally accepted by the Air Force and subsequently turned over to NASA.

The first government X-15 flight (1-3-8) was on 25 March 1960 with NASA test pilot Joseph A. Walker at the controls. The X-15-1 was launched at Mach 0.82 and 45,500 feet, although the stable platform had malfunctioned just prior to release. Two restarts were required on the top engine before all eight chambers were firing, and the flight lasted just over 9 minutes, reaching Mach 2.0 and 48,630 feet. For the next six months, Walker and Major Robert M. White alternated flying the X-15-1.10

It is interesting to note that the predictions regarding flutter made by Lawrence P. Greene at the first industry conference in 1956 did materialize, although fortunately they were not major and relatively easy to correct. During the early test flights, vibrations at 110 cycles had been noted and were the cause of some concern. Engineers at FRC added instrumentation to the X-15s from flight to flight in an attempt to isolate the vibrations and understand their origins, while wind tunnel tests were conducted at Langley. It was finally determined that the vibrations were being caused by a flutter of the fuselage side tunnel panels. These had been constructed in removable sections with an unsupported length of over 6 feet in some cases." North American added longitudinal stiffeners along the underside of each panel, and this largely cured the problem.12

The X-15-1 flew three times in the two weeks between 4 August and 19 August 1960, with five aborted launches due to various problems (including persistent APU failures). Two of these flights were made by Joe Walker, and one by Bob White. The flight on 12 August was to an altitude of 136,500 feet, marking the highest flight of an XLR11 – powered X-15.