THE COSMONAUT SQUAD

So much for the hardware. What about the people who would fly to the moon? The selection of cosmonauts for the moon programme went through a number of phases: [5]

Although no cosmonaut ever did make the trip around the moon or to its surface, we know with a fair degree of certainty who would have made these voyages [23].

Russia drew on its existing teams of cosmonauts for its moon missions. By 1970, the Soviet Union had selected a number of cosmonaut groups. Essentially, Soviet cosmonaut selection was divided into three streams: Air Force pilots and military engineers, who commanded missions; flight engineers, civilians mainly drawn from the design bureaux that made the spacecraft; and specialists, like doctors, selected for specific missions. By the time of the moon programme, the following groups of pilots had been selected:

• Twenty young Air Force pilots for the first manned spaceflights (I960).

• Five young women to make the first flight by a woman into space (1962).

• Fifteen older Air Force pilots and military engineers (1963) (two more joined the group later).

• Twenty young Air Force pilots and military engineers (1965), later called ‘the Young Guards’.

The following groups of civilian engineers had been selected:

• Two engineers, one of whom would fly on the first multi-manned Voskhod flight (1964).

• Six engineers from OKB-1 (1966), with three more joining the following year.

• Three more civilian engineers (1969).

The following specialists were also selected:

• Two doctors (1964).

• Four Academy of Sciences cosmonauts (1967).

Many more cosmonauts were selected subsequently, but too late for the prospective moon missions and they are not considered here (the much later N1-L3M plan never got so far as to merit the selection of cosmonauts). Of the groups above, two were not relevant to the moon programme. The women’s group was selected for the first flight of a woman in space, eventually made by Valentina Tereshkova in 1963. Although there was a number of discussions about further missions by women, none came to fruition and none were ever considered for a moon mission. The group was disbanded in 1969. The two doctors likewise were never considered for the moon mission.

For its moon mission, Russia theoretically had available up to 74 cosmonauts. In reality, the total number available was much smaller, for some had retired or gone on to other work. A small number died during accidents. By far the largest cause for the reduction of numbers was people exiting due to failing medical tests, sometimes caused by the rigorousness of the training regime. A small number was also dismissed for indiscipline.

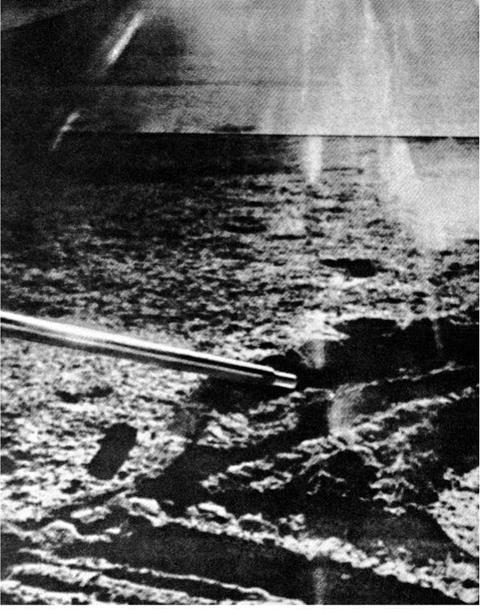

|

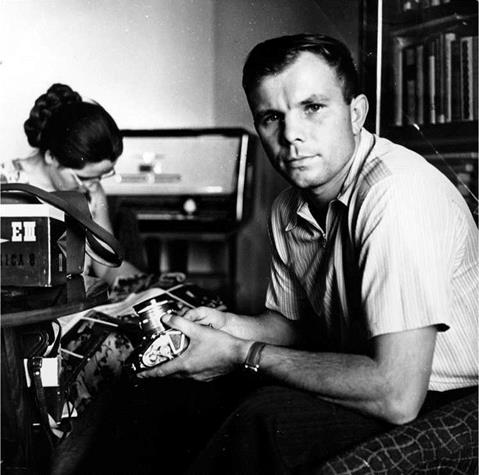

Early Soviet cosmonauts, Sochi, 1961 |

Those chosen for the moon mission were inevitably likely to be drawn from the most experienced members of the groups, especially those who had flown in space before. In more detail, the following is the pool from which they were drawn:

I960 first Air Force pilot selection (20): Ivan Anikeyev, Pavel Belyayev, Valentin Bondarenko, Valeri Bykovsky, Valentin Filateyev, Yuri Gagarin, Viktor Gor – batko, Anatoli Kartashov, Yevgeni Khrunov, Vladimir Komarov, Alexei Leonov, Grigori Nelyubov, Andrian Nikolayev, Pavel Popovich, Mars Rafikov, Georgi Shonin, Gherman Titov, Valentin Varlamov, Boris Volynov, Dmitri Zaikin.

This was the first, original and most famous group of cosmonauts. These were the equivalent of the Mercury seven, selected in April 1959 for the first American mission into space and immortalized in the film The right stuff. Russia’s right stuff comprised young Air Force pilots recruited in 1959-1960. Compared with the American group, they were much younger (24 to 35, but mainly at the younger end) and had much fewer flying hours. Gherman Titov, the second Russian to orbit the Earth, was only 25 years old when he made his mission. Yuri Gagarin, the first man in space, had only 230 flying hours to his credit when he joined the cosmonaut squad (prospective Americans must have a minimum of 1,500). Like the Americans, the Russians put an emphasis on young, tough, fit men in perfect health who could react quickly to difficult situations. Young Air Force pilots, disciplined by military service, were considered to provide the best possible background for the early space missions. China selected a similar type of person for its first yuhangyuan group (1970) and its second one many years later (1996).

Cosmonauts from the moon flights were most likely to be drawn from this group. By autumn 1968, eight members of the group had flown, in this order: Yuri Gagarin, Gherman Titov, Andrian Nikolayev, Pavel Popovich, Valeri Bykovsky, Vladimir Komarov, Pavel Belyayev and Alexei Leonov. There was a high rate of attrition from this group and eight of the group never flew in space at all because of problems,

|

Chief designer Valentin Glushko with cosmonauts |

accidents and even dismissals due to indiscipline. Two died during the moon programme (Vladimir Komarov and Yuri Gagarin).

The first 20 cosmonauts were recruited through the Institute for Aviation Medicine with a view to one of them making the first manned flight into space. A centre for the training of cosmonauts was approved in January I960, called the Centre for Cosmonaut Training, TsPK, the title it still uses. General Kamanin was appointed director of the squad, a position he held until 1971. The first cosmonauts arrived in February 1960, the rest the following month, and work formally began with the first lecture at 9 a. m. on the morning of 14th March 1960. Originally, TsPK was located in an office building belonging to the MV Frunze airfield on Leninsky Prospekt, but in June 1960 the centre moved out to a greenfield location. This was a 310 ha site in birch forest, now known as Star Town (sometimes Star City), 30 km to the northeast of Moscow. A secret location until the 1970s, it was to become the most international space training centre in the world by the 1990s.

Star Town’s weather crosses extremes, ranging from +30°C in high summer to —30°C in the depths of winter. A central focus of Star Town is the man-made lake, which freezes over in winter. Around it may be found accommodation for the cosmonauts and workers at Star Town, comprising 15-floor blocks. Transport is mainly by rail via the nearby Tsiolkovsky railway station or by minibus from Moscow [24]. Star Town comprises accommodation, a museum, nursery, school, health and sports centres and an hotel (called Orbita). It is a closed, guarded, walled town, though

|

Yuri Gagarin at home |

entry is now much easier than in its early days. In the central area may be found, within a further walled area, the cosmonaut training centre: simulators, centrifuge, hydrolab (water tank to test spacewalks), planetarium and running track.

The high attrition rate among the first group of cosmonauts meant that a second main group should be selected and, accordingly, a new group of pilots and military engineers was chosen on 11th January 1963.

1963, second Air Force pilot selection (17): Georgi Dobrovolski, Anatoli Filip – chenko, Alexei Gubarev, Anatoli Kuklin, Vladimir Shatalov, Lev Vorobyov, Yuri Artyukin, Edouard Buinovski, Lev Demin, Vladislav Gulyayev, Pyotr Kolodin, Edouard Kugno, Alexander Matinchenko, Anatoli Voronov, Vitally Zholobov, Georgi Beregovoi, Vasili Lazarev.

This group was selected for the flights of the Soyuz complex. There was an important change in direction in recruitment. There had been concerns over the individualistic bent of some members of the first squad. The cosmonaut selectors now wanted to go for slightly older, more mature pilots who would be less likely to cause discipline problems. Graduation from an institute was a requirement, ruling out young pilots straight out of school. There was more emphasis on education and flying experience, less on physical perfection. Military engineers were included for the first time. This was to prove quite a successful selection group, for many went on to become eminent and reliable cosmonaut pilots in the 1970s. One exception was the unfortunate Eduard Kugno. Strange though it might seem to Westerners, membership of the Communist Party was not a prerequisite for selection to the cosmonaut squad (designer and cosmonaut Konstantin Feoktistov was a famous non-joiner). Kugno went a stage further and when asked why he had not joined, he said he would never join a party of ‘swindlers and lickspittles’. He was promptly dismissed for ‘ideological and moral instability’.

Although by this stage, the cosmonaut squad consisted of over 30 members, the multiplicity of manned programmes under way suggested the need for another round of recruitment. In early 1965, the call went out for more candidates and 20 were selected from the 600 who applied. They were a mixture of pilots and engineers, with one military doctor (Degtyaryov). For this group, the Russians went back to younger pilots in their 20s, but this time making sure that they had stable psychological backgrounds.

1965, third Air Force selection (22) (‘the Young Guards’): Leonov Kizim, Pyotr Klimuk, Alexander Kramarenko, Alexander Petrushenko, Gennadiy Sarafanov, Vasili Shcheglov, Ansar Sharafutdinov, Alexander Skvortsov, Valeri Voloshin, Oleg Yakovlev, Vyacheslav Zudov, Boris Belousov, Vladimir Degtyaryov, Anatoli Fyorodov, Yuri Glazhkov, Vitally Grishenko, Yevgeni Khludeyev, Gennadiy Kolesnikov, Mikhail Lisun, Vladimir Preobrazhenski, Valeri Rozhdestvensky, Edouard Stepanov.

This group was not formed with moon missions in mind at all, but with a view to undertaking, after a lengthy period of training, a range of missions some time in the future. This explains the decision to go for a younger age group. They were accordingly called ‘the Young Guards’. This group did, in the course of time, provide a number of pilots for space station missions in the 1970s, but it also suffered high attrition rates.

Originally, there was a broadly accepted view that ‘right stuff’ cosmonauts must be drawn from the military. The Russians began to recruit cosmonauts from further afield much sooner than the Americans. With the first three-man spaceship in 1964, the Voskhod, there were seats which did not need to be filled by military cosmonaut pilots. Sergei Korolev established the principle that engineers and specialists should also be regular participants on Soviet spaceflights and for the Voskhod mission awarded one seat to a designer, the other to a doctor (Boris Yegorov was the lucky man). For the civilian engineer group, two were selected, of whom one would fly, N-1

|

Yuri Gagarin with Valentina Tereshkova |

and Soyuz complex designer Konstantin Feoktistov. He was now a senior designer in Korolev’s own OKB-1 and had been involved in the design departments from the mid – 1960s. When the opportunity came to fly passengers on Voskhod, he leapt at the chance.

1964 civilian engineers (2): Konstantin Feoktistov, Georgi Katys.

Konstantin Feoktistov was drawn from OKB-1 and Georgi Katys from the Academy of Sciences. This was not intended as a cosmonaut group as such, but as a selection that would train for one mission only and then return to normal duties. Feoktistov did not go back quietly, but pressed persistently but unsuccessfully to get further missions. Medical tests went against him. He continued to offer his opinions on spaceflight history and contemporary issues into the 1990s.

The first substantial group of civilian engineers was recruited by Vasili Mishin on 23rd May 1966. They did not report for training until September and some of those listed joined the group even later.

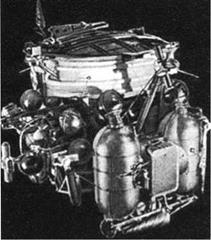

|

Sergei Korolev with Konstantin Feoktistov |

1966 civilian engineers (10): Gennadiy Dolgopolov, Georgi Grechko, Valeri Kubasov, Oleg Makarov, Vladislav Volkov, Alexei Yeliseyev, Vladimir Bugrov, Nikolai Rukhavishnikov, Vitally Sevastianov, Sergei Anokhin (instructor cosmonaut).

Sergei Anokhin was a leading test pilot and put in charge of the group. All were drawn from OKB-1. Despite the worries of the military, there had been no disasters arising from the flying of civilians on Voskhod. The successful flight of Konstantin Feoktistov set the trend for the permanent division of cosmonaut selection into two streams: the military and civilian (with the further category of specialist). Later, it became standard for Russian spacecrews to comprise a military commander and civilian flight engineer. Because of its preeminence in the manned spaceflight programme, almost all the civilians came to be drawn from OKB-1, but in the course of time small numbers were also taken from the other design bureaux and from the Institute of Bio Medical Problems. The rationale behind the civilian selections was that those who knew most about the spaceships were those who designed them. They were the best people to fix them if they went wrong. By contrast, there was no equivalent tradition in the American space programme.

A larger selection of specialists was made several years later: four scientists.

1967 Academy of Sciences (4) : Rudolf Gulyayev, Ordinard Kolomitsev, Mars Fatkullin, Valentin Yershov.

This was the first selection of scientists in the Soviet space programme [25] and was an initiative of the President of the Academy of Sciences, Mstislav Keldysh. The United

|

Cosmonaut Valentin Yershov, lunar navigator |

States had also begun scientist selections at around this time. Eighteen scientists applied for this selection, four reaching the final selection on 22nd May 1967. Gulyayev, Kolomitsev and Fatkullin came from the Institute for Terrestrial Magnetism, Ionosphere and Radio Wave Propagation, while Yershov came from the Institute for Applied Mathematics. Kolomitsev was a true explorer, having spent over four years at the Soviet Antarctic southern magnetic pole Vostok base. The first three hoped to get assignments on Earth-orbiting missions, but Yershov was chosen with the upcoming lunar missions in mind where he would assist as navigator. He had an unhappy background, for his father, a police officer, had been killed by the NKVD secret police. Yershov, born 1928, had developed surface-to-air missiles before joining Keldysh’s Institute for Applied Mathematics in 1956. There he specialized in spacecraft navigation, working on the development of the autonomous navigation system of the L-1 Zond. Yershov even developed a theorem of measurement named partly after him, the Elwing-Yershov theorem.

Finally, a group of three engineers was selected in 1969 and they were the last group whose members entered lunar selections.

1969 civilian engineers (3): Vladimir Fortushny, Viktor Patsayev, Valeri

Yazdovsky.

The last two were drawn from OKB-1, Vladimir Fortushny from the Paton Institute of Welding in the Ukraine. Fortushny was selected with a view to a welding-in-space mission, not for lunar flights (the mission was flown as Soyuz 6 in 1969, but by another cosmonaut, Valeri Kubasov). So this was the pool from which the lunar missions would be drawn.

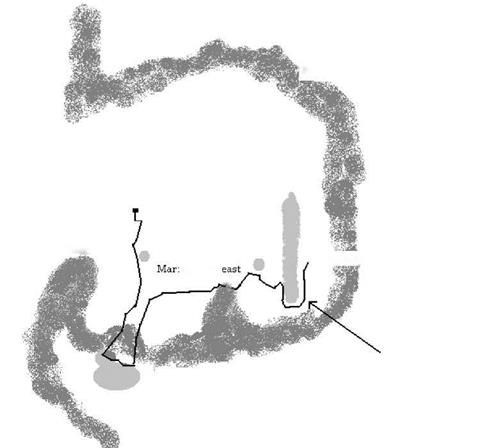

Foothills at crater rim

Foothills at crater rim Landing First signal

Landing First signal

140 x 148 km, 2hr 04min, 40.58°

140 x 148 km, 2hr 04min, 40.58° 25 x 244km for four days 181 x 299 km

25 x 244km for four days 181 x 299 km