STS-96

|

Int. Designation |

1999-030A |

|

Launched |

27 May 1999 |

|

Launch Site |

Pad 39B, Kennedy Space Center, Florida |

|

Landed |

6 June 1999 |

|

Landing Site |

Runway 15, Shuttle Landing Facility, KSC, Florida |

|

Launch Vehicle |

OV-103 Discovery/ET – 100/SRB BI-100/SSME #1 2047; |

|

#2 0251; #3 2049 |

|

|

Duration |

9 days 19 hrs 13 min 57 sec |

|

Call sign |

Discovery |

|

Objective |

ISS assembly flight 2A.1; logistics mission |

Flight Crew

ROMINGER, Kent Vernon, 42, USN, commander, 4th mission Previous missions: STS-73 (1995); STS-80 (1996); STS-85 (1997)

HUSBAND, Rick Douglas, 41, USAF, pilot

JERNIGAN, Tamara Elizabeth, 40, civilian, mission specialist 1, 5th mission Previous missions: STS-40 (1991); STS-52 (1992); STS-67 (1995); STS-80 (1996) OCHOA, Ellen Lauri, 41, civilian, mission specialist 2, 3rd mission Previous missions: STS-56 (1993); STS-66 (1994)

BARRY, Daniel Thomas, 45, civilian, mission specialist 3, 2nd mission Previous mission: STS-72 (1996)

PAYETTE, Julie, 35, civilian, Canadian, mission specialist 4 TOKAREV, Valery Ivanovich, 46, Russian Air Force, mission specialist 5

Flight Log

This mission was the first logistics flight to the station in preparation for the arrival of the Russian Service Module Zvezda (“Star”) scheduled for later in 1999. Due to weight limitations on the previous STS-88 mission, not all the logistics could be taken to the station in one go. STS-96 was originally planned for later in the year, after STS-93 had deployed the Chandra X-ray telescope, but early in 1999 there were problems in the circuitry boards on Chandra which needed to be replaced, forcing the launch to be delayed. In early May, weather damage to the ET intended for STS-96 resulted in further delays for repairs. With the Russian Service Module also being delayed, further ISS Shuttle missions and the arrival of the first resident crew were put back until 2000. This meant there would be a long gap in ISS-related missions between STS-88 and support missions for the first resident crew in 2000. This gap was filled only with the STS-96 logistics mission.

After the STS-96 stack was returned to the VAB for ET tank repairs, during which 460 critical divots out of a total of 650 divots in the ET outer foam were

|

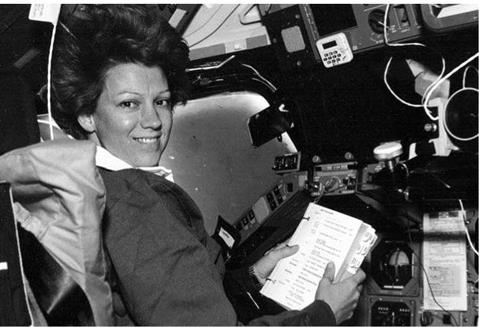

On board the Zarya module, astronauts Julie Payette (top) and Ellen Ochoa handle supplies being moved over from the docked Shuttle Discovery |

repaired, the only other concern prior to launch was when a sail-boarder ventured into the SRB recovery zone. Once that was removed, the launch proceeded smoothly. Two days after launch, Discovery completed the first docking with ISS. The Shuttle remained docked to ISS for 138 hours, during which members of the crew spent over 79 hours inside the station and 7 hours 55 minutes hours outside during the mission’s only EVA. During the 28 May EVA, Jernigan (EV1) and Barry (EV2) transferred the US-built Orbital Transfer Device crane and elements of the Russian Strela crane from the cargo bay of Discovery to their locations on the exterior of the station. They also installed EVA foot restraints that could accommodate either American or Russian EVA footwear and three bags of tools and handrails for future assembly operations. An insulation cover was placed over a trunnion pin on Unity, they inspected one of

two Early Communication Systems (Е-Com) antennas on Unity, and finally photo- documented the exterior paint surfaces of both modules.

Upon entering the station, the crew were concerned over the quality of air circulation inside Zarya, but this was solved by changing the orientation of panel doors that were interrupting the flow of air around the station. Eighteen battery recharge controllers were replaced in Zarya and mufflers were installed over fans inside the FGB to reduce noise levels in the module. The crew also transferred over 1,618 kg of logistics across to the ISS, including clothing, sleeping bags, spare parts, medical equipment and 318 litres of water. They also installed the first of a series of strain gauges, which would be important as the station expanded to record the stress on docking interfaces, and cleaned filters and checked smoke detectors. Transferred in the opposite direction was 90 kg of equipment (198 items), which was moved back into Discovery for the return to Earth.

The day before undocking, the RCS on Discovery were pulsed 17 times to boost the station’s orbit slightly, pending the arrival of the next Shuttle (which turned out to be a year later). Discovery was undocked from ISS on 4 June and after flying two circuits around the station for photo-documentation, the crew prepared for the return to Earth. One of their last tasks prior to landing was the release of a small reflective satellite, which would be a target for student observations around the world.

Milestones

212th manned space flight

124th US manned space flight

94th Shuttle mission

28th flight of Discovery

2nd Shuttle ISS mission

1st Discovery ISS mission

1st Shuttle mission to dock with ISS

|

Flight Crew

COLLINS, Eileen Marie, 42, USAF, commander, 3rd mission Previous missions: STS-63 (1995); STS-84 (1997)

ASHBY, Jeffrey Shears, 45, USN, pilot

COLEMAN, Catherine Grace (“Cady”), 38, USAF, mission specialist 1,

2nd mission

Previous mission: STS-73 (1995)

HAWLEY, Steven Alan, 47, civilian, mission specialist 2, 5th mission Previous missions: STS 41-D (1984); STS 61-C (1986); STS-31 (1990);

STS-87 (1997)

TOGNINI, Michel Ange Charles, 49, French Air Force, mission specialist 3, 2nd mission

Previous mission: Soyuz TM15 (1992)

Flight Log

If the launch of STS-93 had occurred on time on 20 July, Eileen Collins, the first female commander of a US space mission, could have taken Columbia to orbit on the 30th anniversary of the Apollo 11 lunar landing (whose Command Module was also called Columbia). However, the launch was terminated at the T — 7 second mark when more than double the permitted amount of hydrogen was detected in the aft engine compartment of the orbiter. System engineers in the firing room at KSC noted the indication and manually cut off the ground launch sequencers less than a second before SSME ignition. Post-abort evaluation determined that the reading was false. The next launch attempt, on 22 July, was scrubbed due to adverse weather conditions at KSC, but the launch attempt on 23 July was successful, the only delay being a communications problem with Columbia during the countdown which forced a seven minute slip in the launch time.

|

Eileen Collins, the first female Shuttle commander and first female commander of an American mission, looks over a checklist at the commander’s station on the forward flight deck of Columbia during FD 1 |

Five seconds after leaving the pad, flight controllers noted a voltage drop in one of the electrical buses on the Columbia. As a result of the drop in voltage, one of two redundant main engine controllers on two of the three SSME (centre and right position) shut down. But the others performed nominally, supporting the climb to orbit. However, the orbit attained was 11.2 km lower than planned due to the premature cut-off of the SSME. This was later traced to a hydrogen leak in the #3 main engine nozzle, caused by the loss of an LO pin from the main injector during engine ignition. This had struck the hot wall of the nozzle and ruptured three LH coolant tubes.

Columbia’s manoeuvring engines were used subsequently to raise the orbit to its proper altitude, allowing the deployment of the primary payload into its desired orbit. The Chandra X-Ray Observatory (formerly known as the Advanced X-Ray Astrophysical Facility, or AXAF) was successfully deployed using its two-stage IUS on FD 1. The IUS propelled the observatory into an operational orbit of approximately 10,000 x 140,000 km – at its farthest, almost one-third of the way to the Moon – in an orbital period of about 64 hours. This would permit the telescope to make 55 hours of uninterrupted observations each orbit. The primary mission of Chandra was scheduled to last five years through to 2004, although this was subsequently extended to ten years of operational activity until 2009.

During the remainder of the mission, secondary payloads and experiments were activated. These included the South-Western UV Imaging System (SWUIS) used to obtain UV imagery of Earth, the Moon, Mercury, Venus and Jupiter. The crew monitored several plant growth experiments and collected data from a biological cell culture experiment. They also evaluated the Treadmill Vibration Information System, which measured vibrations and the changes in microgravity levels caused by on-orbit exercise periods. This was important for gathering data to ensure that exercise periods on ISS did not disrupt delicate instruments and experiments. The crew also evaluated high-definition TV equipment for future use on both the Shuttle and ISS, which conformed to the latest industry standards for TV products. Tognini, who visited the Mir space station in 1992, spoke over the radio with his colleague and fellow countryman Jean-Pierre Haignere, who was on the fifth of his six-month stay on the Russian Mir space station. Collins and Ashby also evaluated the Portable In-flight Landing Operations Trainer (PILOT), which utilised a laptop computer, simulation software and a joystick combination to provide refresher and skills training to the commander and pilot prior to performing the actual landing.

Milestones

213th manned space flight 125th US manned space flight 95th Shuttle mission 26th flight of Columbia

1st female Shuttle commander and 1st US female crew commander (Collins) Shortest scheduled flight since 1990

ISS EO-5 |

|

Int. Designation |

N/A (launched on STS-111) |

|

Launched |

5 June 2002 |

|

Launch Site |

Pad 39A, Kennedy Space Center, Florida |

|

Landed |

7 December 2002 (aboard STS-113) |

|

Landing Site |

Shuttle Landing Facility, KSC, Florida |

|

Launch Vehicle |

STS-111 |

|

Duration |

184 days 22hrs 14 min 23 sec |

|

Call sign |

Freget (Frigate) |

|

Objective |

ISS-5 expedition programme |

Flight Crew

KORZUN, Valery Nikolayevich, 49, Russian Air Force, ISS-5 and Soyuz

commander, 2nd mission

Previous mission: Soyuz TM24 (1996)

WHITSON, Peggy Annette, 42, civilian, ISS-5 science officer TRESCHEV, Sergei Vladimiriovich, 43, civilian, Russian ISS-5 flight engineer

Flight Log

The fifth expedition to the ISS featured a science programme of 24 American and 29 Russian experiments. Whitson had the added privilege of performing an experiment during her mission on ISS for which she was principle investigator. The renal stone experiment was a research programme to study the possible formation of kidney stones during prolonged space flight. Whitson kept regular logs of her food intake and took a regular course of tablets of either potassium citrate or a placebo. By mid-July, the ESA glove box facility had been activated, but communication problems with the new unit meant that Whitson had to forego regular daily exercises for a couple of days while the problems were resolved.

During the residency, the crew received two Progress re-supply craft. In late June, Progress M1-8 was replaced by Progress M46, which delivered 2,580 kg of cargo for the crew and 825 kg of fuel. Three months later, Progress M1-9 replaced the M46 ferry and brought over 2,600 kg of cargo, including equipment for the ESA Odessa science programme in November. These regular re-supply flights were the lifeline of the station’s main crew, supplementing the heavy lift capability of the Shuttle, and serving as an orbital refuse collection service once the new cargo had been unpacked.

August was mainly focused on EVAs. The first (16 Aug for 4 hours 25 minutes) saw Whitson and her commander start late due to a caution and warning signal that indicated a fault on their Orlan pressure suits. Recycling the pre-EVA operations to fix the problem meant that the EVA started 1 hour and 43 minutes late. The two crew members used the Strela boom to access the work area to place six (of an eventual 23)

|

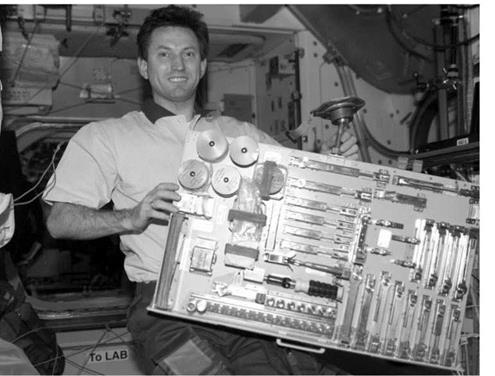

Cosmonaut Sergei Treshchev, ISS-5 flight engineer, holds a special pallet containing various tools used for orbital repairs and DIY aboard the station |

micrometeoroid protection panels on the Zvezda module. Due to the late start, the installation of a Kromka detector, and the gathering of samples of thruster residue on the surface of Zvezda caused by other thrusters on the module, would be rescheduled for later EVAs. The second excursion (26 Aug for 5 hours 21 minutes) was also delayed 27 minutes, this time by a small leak from the pressure seals between Zvezda transfer compartments and where Pirs was docked to it. Recycling the hatch valves seemed to solve the problem. The cosmonauts set up TV cameras to record their activities, as well as an external Japanese experiment for specialists back in Japan. They also deployed the Kromka-2 deflector plate evaluator and retrieved an earlier plate to be returned to Earth for analysis, as well as deploying the final two ham radio antennas.

The ISS-5 crew received the STS-112 Shuttle crew in October (who delivered the S1 Truss), as well as the fourth visiting crew in the new spacecraft Soyuz TMA in November. After just over a week aboard the station, the visiting crew departed in the older TM34, marking the final re-entry and landing of that variant of the venerable Soyuz. Shortly after the departure of the visiting crew, STS-113 arrived with the replacement ISS-6 resident crew, returning home with the ISS-5 crew.

During their residency, the ISS-5 crew encountered and overcame a number of equipment problems, and conducted repairs and maintenance. Whitson wrote a series of journals about life and work on board ISS that were posted on the NASA web site and provided a fascinating insight into life aboard the station. On 16 September, NASA designated her the first NASA science officer, a designation that would be assigned to an American member of each crew from now on. She later wrote that the title was fine, apart from the number of emails she had received from friends all likening her to Mr. Spock, the science officer of the USS Enterprise in the original Star Trek.

Milestones

5th ISS resident crew

4th ISS EO crew to be launched by Shuttle 1st designated NASA science officer (Whitson)

The Next StepsWith the successful flight of STS-114 in July 2005 and the second Return-to-Flight mission of STS-121 in July 2006, NASA revised the Shuttle manifest pending the retirement of the vehicle in 2010. There is also another servicing mission planned for the Hubble Space Telescope in 2008.

Dates listed are subject to change. There will continue to be additional Progress and Soyuz flights for crew transport, logistics and re-supply. Manned variants8K72K (Vostok 1961-3). This version featured an upper stage (Blok E) with a single RO-7 engine, burning LOX/kerosene with a thrust of 5.6 tons and a 430-second burn time. Used to launch the six manned Vostok missions, its design was not revealed to the west until it appeared at the 1967 Paris Air Show. 11A57 (Voskhod 1964-5). This was an improved variant of the Vostok launcher, with an upper stage powered by the RD-108 engine with a vacuum thrust of 30.4 tons and 240-second burn time. This was used to launch the two manned Voskhod spacecraft. 11A511 (Soyuz 1967-76). This version was developed from 1963 to specifically launch the Soyuz spacecraft. The upper stage (Blok I) had an RD-110 engine with a 30.4 ton thrust and 246-second burn time. These vehicles launched the early Soyuz missions, starting with Soyuz 1 in 1967. Its final use was for the Soyuz 23 spacecraft in 1976. With the Soyuz payload and launch shroud, this vehicle measured about 49.3 m (162 ft) in height. 11A511U (Soyuz-U). An upgraded variant of the standard Soyuz booster, this was first used for the launch ofSoyuz 16in 1974 and was in service for over 27 years. Itwas used for launching the Soyuz, Soyuz T and Soyuz TM variants, as well as the Progress and Progress M re-supply vessels. It was also used to deliver the Pirs facility to ISS in September 2001. This vehicle used improved engines, ground and support facilities, increasing the payload mass and orbital delivery altitude. 11AIIU2 (Soyuz U2). Further improvements to payload delivery mass led to this variant of launcher being used for the first time on a Soyuz launch with Soyuz T12 in July 1984. It was last used on Soyuz TM22, after which the production of Sintin (synthetic kerosene) for improved first-stage launch performance ceased in 1996. Soyuz FG. Upgrades to the engines resulted in the RD-108A central core engine, which developed a vacuum thrust of 101,931 kg and had a 286-second burn time. The RD-107A engines provided a thrust of 104.1 tons and a 120-second burn time. Both engines burned LOX/kerosene. This variant was first used for manned launches on Soyuz TMA1 in October 2002 and is the variant currently in use. Soviet lunar plansThe Soviet Union had an even more ambitious plan for a manned landing on the Moon. An N1 mega-booster would launch two cosmonauts to the Moon aboard a combined Soyuz orbiter-lander vehicle. After entering orbit, one cosmonaut would spacewalk from the orbiter to the attached lunar lander inside the upper stage and enter the lander. He would then separate the lander and descend to the surface, spending a few minutes on the ground planting a flag and collecting some rocks before heading back for a rendezvous with the mother ship, where he would spacewalk back to the cabin. The orbiter would then fly home for a Soyuz-type landing. The N1 programme was a disaster, with catastrophic launch failures, and the Moon landing plan was simply over-ambitious. A series of unmanned Zond missions tested various elements of the circumlunar manned programme with varying success between 1968 and 1970, but the whole thing was left without a purpose after the Americans reached the Moon in 1969. GEMINI 7 |

STS-4 |

|

Int. Designation |

1982-O65A |

|

Launched |

27 June 1982 |

|

Launch Site |

Pad 39A, Kennedy Space Center, Florida |

|

Landed |

4 July 1982 |

|

Landing Site |

Runway 22, Edwards Air Force Base, California |

|

Launch Vehicle |

OV-1O2 Columbia/ET-5/SRB A13; A14/SSME #1 2OO7; #2 2OO6; #3 2OO5 |

|

Duration |

7 days 1 hr 9 min 31 sec |

|

Callsign |

Columbia |

|

Objective |

Fourth and final orbital flight test (OFT-4); first DoD classified payload |

Flight Crew

MATTINGLY, Thomas Kenneth II, 46, USN, commander, 2nd mission Previous mission: Apollo 16 (1972)

HARTSFIELD, Henry Warren “Hank” Jr., 48, USAF, pilot

Flight Log

The first military payload to fly aboard a US manned spacecraft was designated DoD – 82-1. Not much detail was released and because of this secrecy, the STS-4 mission marked a change in media relations. The openness of NASA was restricted by the Department of Defense. Conversations with the crew would be classified for most of the mission and photographs taken during it would be limited to those that did not show any classified hardware. STS-4, which was the first US mission to be flown by astronauts without a back-up crew, was not entirely classified because apart from the range of science and declassified payloads, the DoD-82-1 was known to be the Cirris cryogenic infrared radiance instrument to obtain spectral data on the exhausts of vehicles powered by rocket and air breathing engines, and an ultraviolet horizon scanner. Cirris would not perform well, because its lens cap didn’t come off!

The first on-time Shuttle launch, at 11: OOhrs local time, was handled extremely matter-of-factly by young Mark Hess, the NASA press officer, making his first launch commentary. Commander Ken Mattingly and his sidekick Hank Hartsfield sailed into 28.5° inclination orbit, the lowest for a manned space flight but one that would become fairly usual for a Shuttle mission, with a maximum altitude during the mission of 275 km (127 miles). This was still 7 km (4 miles) shorter than planned after the heavier than planned launch weight, caused by water under the heat shield tiles which had collected after a thunderstorm days before launch, and which resulted in an increased SSME burn time of 3 seconds and several OMS burns. In addition, the

|

The STS-4 crew is greeted by President and Mrs Reagan after completing their mission on America’s 206th birthday |

two SRBs were lost in the Atlantic rather than recovered as planned, as a result of parachute failures.

The first US commercial payload in space, more than nine experiments from Utah University crammed inside Getaway Special (GAS) canisters in the payload bay, began operating together with over 20 others packed aboard the busy Columbia orbiter. The mission seemed to have been a spectacular success, despite the Cirris lens cap saga, which Mattingly tried to knock off with the RMS and even suggested that he make a spacewalk to rectify. He did try out the EVA suit in the airlock as planned, however. President Reagan was waiting at Edwards Air Force Base to greet the returning crew, which landed on the concrete runway 22 at a speed of 374 kph (232 mph), at main gear touchdown time of 7 days 1 hour 9 minutes 40 seconds. The Independence Day celebrations seemed complete amid the patriotic fervour but were left a little damp by the President’s lacklustre support for a space station. The Shuttle was rather too enthusiastically declared “operational” as from its next flight.

Milestones

86th manned space flight

35th US manned space flight

4th Shuttle flight

4th flight of Columbia

1st US manned military space flight

1st US manned space flight without a back-up crew

1st manned space flight to carry an official commercial payload

|

Flight Crew

POPOV, Leonid Ivanovich, 36, Soviet Air Force, commander, 3rd mission Previous missions: Soyuz 35 (1980); Soyuz 40 (1981)

SEREBROV, Aleksandr Aleksandrovich, 38, civilian, flight engineer SAVITSKAYA, Svetlana Yevgenyevna, 34, civilian, research engineer

Flight Log

A Soyuz with a difference lit up the Baikonur skies at 23: 12hrs local time on 19 August, when a crew of three lifted off for a visiting mission to Salyut 7. This crew included the first female in space for 19 years, since the first, Valentina Tereshkova, was launched. While Tereshkova’s mission was mere propaganda, the inclusion of Svetlana Savitskaya, bona fide test pilot and a world aerobatic champion, seemed logical and acceptable – except that she just happened to beat the first American female, Sally Ride, into space.

Amid much ballyhoo and publicity, as well as live TV coverage, Savitskaya and her two seemingly anonymous male colleagues docked with Salyut about 25 hours after launch. The Salyut 7 resident, Valentin Lebedev, gave her an apron and told her to start work. Savitskaya’s main task was not to do the washing up, but to operate a series of life sciences experiments to study the cardiovascular system, motion sickness and eye movement. She also operated an electrophoresis experiment to separate cells. Popov, Serebrov and Savitskaya landed in Soyuz T5 at T + 7 days 21 hours 52 minutes 24 seconds, 112 km (70 miles) northeast of Arkalyk. Maximum altitude reached during the 51.6° mission was 315 km (196 miles).

Milestones

87th manned space flight 52nd Soviet manned space flight

45th Soyuz manned space flight 6th Soyuz T manned space flight

|

1st manned space flight by mixed female and male crew

STS 51-F |

|

Int. Designation |

1985-063A |

|

Launched |

29 July 1985 |

|

Launch Site |

Pad 39A, Kennedy Space Center, Florida |

|

Landed |

6 August 1985 |

|

Landing Site |

Runway 23, Edwards Air Force Base, California |

|

Launch Vehicle |

OV-099 Challenger/ET-19/SRB BI-017/SSME #1 2023; #2 2020; #3 2021 |

|

Duration |

7 days 22 hrs 45 min 26 sec |

|

Callsign |

Challenger |

|

Objective |

Spacelab 2 research programme; verification of Spacelab Igloo/pallet configuration |

Flight Crew

FULLERTON, Charles Gordon, 48, USAF, commander, 2nd mission Previous mission: STS-3 (1982)

BRIDGES, Roy Dunbard Jr., 42, USAF, pilot HENIZE, Karl Gordon, 58, civilian, mission specialist 1 MUSGRAVE, Franklin Story, 49, civilian, mission specialist 2 ENGLAND, Anthony Wayne, 43, civilian, mission specialist 3 ACTON, Loren Wilbur, 49, civilian, payload specialist 1 BARTOE, John-David, 40, civilian, payload specialist 2

Flight Log

The highly esoteric astronomical observation Spacelab 2 science payload had been proposed a decade before and the mission itself had been in preparation for over five years and, at last, 51-F was ready. On 12 July, on Pad 39A all three main engines were up and running with three seconds to go before lift-off, when the hydrogen chamber coolant valve on engine 2 failed to close. A computer ordered a redundant command to be made but mission rules dictated a launch pad abort, called an RCLS abort. As an abort had already occurred on STS 41-D, the event was not greeted with so much drama, although to the crew, which included Karl Henize (who was waiting to be the new oldest man in space after an 18-year wait for a flight), it was a bitter disappointment.

It was also a disappointment to the scientists, because a later launch in less than perfect lighting conditions, as there would be more moon shine, would degrade three of the thirteen primary experiments, mounted on pallets in the payload bay. Challenger tried again on 29 July, and until T + 4 minutes 55 seconds, the launch went well, after a 1 hour 37 minute hold due to incorrect telemetry. The crew had a close eye on the centre engine which was apparently overheating early after lift-off and watched

|

helplessly as an indicator showed it had shut down, just 33 seconds after Challenger would have had to have performed a transatlantic abort, possibly ditching into the sea and sinking. As it was, an abort-to-orbit was ordered, and at the flick of a switch commander Fullerton initiated a new flight programme. Later, another engine appeared to be overheating and if the crew had not been told to inhibit what was suspected to have been an over-zealous sensor, a worse abort would have resulted.

Challenger struggled into a 49.5° orbit and its OMS engines placed it at a peak altitude of 276 km (171 miles), much lower than had been planned for the Spacelab mission. The use of the OMS engines also restricted flight experiments using the free – flying Plasma Diagnostic Package payload. Nonetheless, the Shuttle had at least reached orbit, in which the busy crew worked in two 12-hour shifts on the vast array of science experiments. These included the Instrument Pointing System (IPS), which did not quite achieve its advertised 1 arc-second of pointing accuracy.

Despite the abort-to-orbit situation, the significant mission re-planning allowed the flight to be deemed a success. As well as verification of the IPS, the flight also featured part of the modular Spacelab system called the Igloo, which was placed at the front of the three-pallet “train” in the payload bay and designed to provide in-flight support to the instruments that were installed on each of the pallets. The main objective of STS 51-F was to verify the Igloo, pallet and IPS system and its interface with the orbiter, in addition to monitoring the immediate environment around the orbiter, which may or may not interfere in the gathering of scientific data. The experiment programme for the flight encompassed life sciences, plasma physics,

astronomy, high-energy astrophysics, solar physics, atmospheric physics, and technology research. This latter category included an evaluation of new beverage containers by the crew. Coke and Pepsi cans, with specially adapted mouth dispensers to both retain the carbonated drinks’ condition and prevent it leaking into the cabin, were evaluated. The system worked but the taste did not, and according to the astronauts who tried the drinks, having extra gas in the digestive system when in space is not the most enjoyable feeling or experience.

Challenger’s performance was so good that an extra day was offered to the crew, which turned it down and came home to runway 23 at Edwards Air Force Base, at T + 7 days 22 hours 45 minutes 26 seconds.

Milestones

108th manned space flight

50th US manned space flight

19th Shuttle flight

8th flight of Challenger

1st Spacelab pallet only science mission

Henize becomes oldest person to fly in space (58)

. SOYUZ TM10Flight Crew MANAKOV, Gennady Mikhailovich, 40, Soviet Air Force, commander STREKALOV, Gennady Mikhailovich, 49, civilian, flight engineer, 4th mission Previous missions: Soyuz T3 (1980), Soyuz T8 (1983), Soyuz T10-1 (1983); Soyuz T11 (1984) Flight Log The two Gennadys comprised the seventh Mir resident crew and were launched with four live Japanese quails for the Inkubator 2 experiment on board Mir. They would be used in “adaptation to weightlessness” experiments. During the two-day flight to Mir, one of the older quails “laid” an egg and this was returned to Earth with the TM9 crew. The TM10 spacecraft docked with the rear port of Kvant 1 on 3 August. Following the period of handover from the TM9 crew, which included a rather extensive review of where everything was stored, the new crew had a relatively quiet residency aboard the station. Their mission had been delayed ten days to allow the Mir-6 crew to complete their commissioning of systems aboard the Kristall module. During their residency aboard Mir, Manakov and Strekalov had the primary engineering task of rewiring the base block’s power supply, as well as attempting to repair the Kvant 2 EVA hatch that had been damaged during the previous mission. They would also continue the wide programme of scientific work aboard the complex. After a long and frustrating wait, Strekalov finally achieved his goal of a long – duration mission, having previously flown to Salyut 6 and 7 on short visiting missions. He was also a hardened veteran space explorer, having been a crew member of the 1983 Soyuz T8 docking abort and the T10-1 launch pad abort. In boarding Mir, he became one of the first cosmonauts to visit three separate space stations. The only EVA of the mission had been planned for 19 October, but Strekalov developed a head cold, delaying it until 30 October. When the two cosmonauts inspected the damaged

hinge plate they were scheduled to replace, it was found to be deformed beyond repair. Instead, they installed a special latch to ensure that the hatch could be closed and used until fully repaired. With the repair task not deemed to be urgent, it was deferred to the next resident crew, who would fit a replacement unit. The EVA lasted 3 hours 45 minutes. During this mission, the station was supplied by two Progress cargo craft. Progress M4 docked on 17 August, delivering power cables and TV equipment for the upcoming Japanese commercial mission. Before it was undocked, the crew attached a small experiment to the docking assembly, which was activated on 17 September when the ferry undocked. During station keeping, about 100 metres from Mir, artificial plasma was created around the Progress and this was filmed by the cosmonauts. Progress M5, which arrived on 29 September, carried more TV equipment for the Japanese mission. It also featured the first Raduga recoverable capsule system that could return about 150 kg of experiment material, the trade-off being a reduction in the cargo capacity of the vehicle. The Raduga capsule featured a truncated cone that would eject from the descending Orbital Module at about 120 km, just prior to the module’s fiery destruction in the atmosphere. At 15,000 metres, air pressure sensors successfully triggered the parachute deployment and Raduga was successfully retrieved. It returned 115 kg of payload. The 7th expedition completed their mission on 10 December, returning to Earth in the TM10 capsule along with the first Japanese cosmonaut, TV journalist Toyohiro Akiyama, who had arrived with the 8th expedition crew in Soyuz TM11 on 4 December. Milestones 134th manned space flight 69th Soviet/Russian manned space flight 62nd Soyuz manned space flight 9th Soyuz TM manned space flight 17th Soviet and 40th flight with EVA operations 7th Mir resident crew 1st use of the Raduga return capsule Strekalov celebrates his 50th birthday in orbit (28 October)

|