Vostok and Voskhod

Vostok 1 weighed 4,726 kg (10,419 lb) and comprised a spherical flight module and an instrument section, shaped like a double cone, containing batteries and a retro-rocket. The total length of the spacecraft was 4.4m (14.4ft), with a maximum diameter of 2.43 m (7.97 ft). The habitable module was 2.3 m (7.55 ft) in diameter and weighed 2,240 kg (4,938 lb). Vostok was designed to support life for ten days in an orbit low enough to guarantee a re-entry due to natural decay in that period, in case of retro- rocket failure. The instrument section, weighing 2,270 kg (5,004 lb) and measuring

|

The first cosmonauts of Vostok and Voskhod -1 to r Komarov, Feoktistov, Gagarin, Leonov, Titov, Bykovsky, Tereshkova, Popovich, Belayev, Yegorov, Nikolayev (AIS collection) |

2.25 m (7.38 ft) long, utilised the TDU 1 retro-engine, powered by nitrous oxide and an amine-based fuel, with a thrust of 1.6 tonnes and a burn time of 45 seconds. The flight module landed at 10m/sec (32.8 ft/sec) – enough to injure the passenger seriously – so the pilot ejected at a height of 7 km (4 miles) and parachuted separately to the ground, landing at a speed of 5m/sec (16.4 ft/sec). The Vostok capsule had been tested three times successfully in six attempts on Korabl-Sputnik 1-5 (known in the West as Sputnik 4, 5, 6, 9 and 10), four of which carried canine passengers. Another caninecarrying mission failed to reach orbit. Other missions were planned but were cancelled in favour of upgrading the spacecraft into what became Voskhod as an interim measure to compete with the US Gemini series of missions.

Voskhod was essentially a Vostok spacecraft without crew ejector seats and with a back-up retro-rocket pack on top. It also had a landing retro-rocket system. The spacecraft weighed 5,320kg (11,730lb), comprising the 2,900kg (1,802lb) flight Descent Module, a 2,280 kg (5,027 lb) Instrument Module and a 145 kg (320 lb) back-up retro-pack. It was 5 m (16 ft) high, with a maximum diameter of 2.43 m (8 ft). The back-up retro-rocket – needed because Voskhod’s orbit, higher than Vostok on the more powerful SL-4 booster, would not naturally decay in ten days in the event of retro-fire failure – had a thrust of 12 tonnes and comprised 87 kg (192 lb) of solid propellant. It resembled an inverted cup on top of the Descent Module. To enable a 0.2 m/sec (0.65 ft/sec) landing, compared with the Vostok landing speed of 8 to 10m/sec (26-32 ft/sec), a landing retro-rocket was added, deployed with the parachute so that it fired downwards in front of the Descent Module. Voskhod flew one unmanned test flight, Cosmos 47, six days before the first manned flight. Voskhod 2 weighed 5,683 kg (12,531 lb). The main difference compared with Voskhod 1 was the flexible airlock, which was approximately 2.13 m (7 ft) long and 0.91 m (3 ft) in diameter. This was jettisoned after the EVA. The payload fairing of the SL-4 launch vehicle was modified to include a blister-like covering for the stowed airlock which protruded slightly from the flight capsule. Again, an unmanned craft (Cosmos 57) flew three weeks before Voskhod 2. There was also a 22-day canine flight flown as Cosmos 110 in early 1966, and a series of other manned Voskhod flights were planned, but they were cancelled in a desire to move on to the more advanced Soyuz programme.

Mercury

The US Mercury capsule was even smaller, with the pilot “putting it on”, rather than getting into it, as some astronauts described the entry. It would splashdown at sea under a single parachute.

The Mercury capsule was a bell-shaped spacecraft, 2.87 m (9.41ft) high, with a maximum diameter across the heat shield base of 1.85m (6.07 ft). At lift-off, with a launch escape system tower on its top, Mercury weighed about 1,905 kg (4,200 lb). The attitude of the heavily instrumented but severely cramped capsule would be changed by the release of short bursts of hydrogen peroxide gas from 18 thrusters located on the

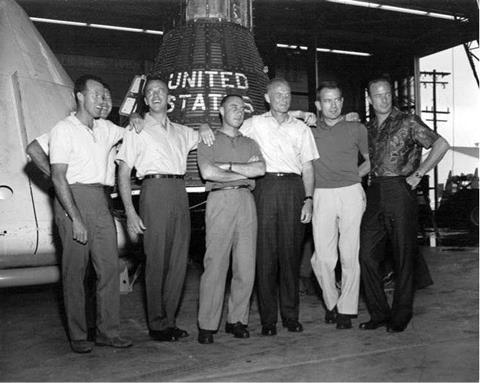

|

The Original Seven Mercury astronauts pose by a Mercury capsule and an Apollo CM at the Manned Spacecraft Center in Houston, Texas, during Look magazine’s coverage of the Collier Trophy Award in June 1963. L to r are Cooper, Schirra (partially hidden), Shepard, Grissom, Glenn, Slayton and Carpenter |

craft. These movements could be controlled by the Automatic Stability and Control System (ASCS, which acted as the craft’s “autopilot” from the ground), through the Rate Stabilisation Control System (RSCS), or manually by the astronaut using a hand controller connected to a fly-by-wire system. At the back of the capsule, over an ablative heat shield, was a retro-pack containing three solid propellant rockets. These were held to the heat shield by three metal “straps” which were deployed along with the heat shield during re-entry. Mercury descended to a sea landing, or “splashdown” under one main parachute. Just before splashdown, the heat shield was dropped 1.21 m (4 ft), pulling out a rubberised fibreglass landing bag to reduce shock. Mercury had been tested unmanned 17 times previously on various rockets, only seven times successfully. Freedom 7 was Mercury capsule 7, the only first-production run, manrated capsule and the only one to fly manned with one circular porthole, rather than a larger rectangular window, one of several new features requested by the astronauts but not included in time for MR3. Mercury capsule No. 11 (for MR4 the second suborbital mission) was in fact the first operational capsule designed for orbital flights, and included a rectangular window and an explosive side hatch, recommended by the astronauts for safety purposes.

Both Vostok and Mercury made six single-person flights between 1961 and 1963. Mercury was succeeded by a larger two-person craft called Gemini, while Vostok basically became Voskhod, into which a three-man crew was crammed for the maiden flight in 1964. A second flight included the first spacewalk, performed in 1965. These two flights in a sense diverted the Soviet Union from its lunar goal, because they were flown for short-term prestige.