STS-32

|

Int. Designation |

1990-002A |

|

Launched |

9 January 1990 |

|

Launch Site |

Pad 39A, Kennedy Space Center, Florida |

|

Landed 20 |

January 1990 |

|

Landing Site |

Runway 22, Edwards Air Force Base, California |

|

Launch Vehicle |

OV-102 Columbia/ET-32/SRB BI-035/SSME #1 2024; |

|

#2 2022; #3 2028 |

|

|

Duration |

10 days 21hrs 0min 36 sec |

|

Callsign |

Columbia |

|

Objective |

Satellite deployment and LDEF retrieval mission |

Flight Crew

BRANDENSTEIN, Daniel Charles, 46, USN, commander, 3rd mission Previous missions: STS-8 (1983); STS 51-G (1985)

WETHERBEE, James Donald, 37, USN, pilot

DUNBAR, Bonnie Jean, 40, civilian, mission specialist 1, 2nd mission Previous mission: STS 61-A (1985)

IVINS, Marsha Sue, 38, civilian, mission specialist 2 LOW, George David, 33, civilian, mission specialist 3

Flight Log

When the Long Duration Exposure Facility (LDEF) was deployed in 1984, the plan was that it would be retrieved the following year. The NASA Space Shuttle manifest got itself into a real pickle under pressure from all directions and had to push the LDEF retrieval mission into September 1986. That would have been flight STS 61-L, commanded by Don Williams, piloted by Mike Smith-who was also assigned to 51-L Challenger – and with mission specialists Bonnie Dunbar, James Bagian and Manley Carter. After the Shuttle programme had recovered from the Challenger accident, the LDEF retrieval mission was assigned to STS-32 with the lone survivor from 61-L, Bonnie Dunbar. The commander of what was going to be one of the more high-profile Shuttle missions was the new chief of the astronauts, Dan Brandenstein.

STS-32 was subject to several delays, partly due to the longer time in getting the orbiter Columbia spaceworthy. Eventually, Columbia was rolled out to Pad 39A just after the launch of STS-33 and would be the first Shuttle to take off from this refurbished pad since STS 61-C in January 1986. It was set for a mammoth ten-day mission, starting on 18 December and taking in a Christmas in space, but problems bringing the new pad on line for launches meant a delay first to 21 December, then for three weeks to 8 January. NASA felt it prudent to give the launch and support teams a full holiday.

|

STS-32 retrieves LDEF after almost six years in space |

As the crew left their quarters on 8 January, they knew they would be coming back the same day because the weather gave them less than a ten per cent chance of taking off. Going through a full countdown to T — 5 minutes, however, provided a good opportunity to give Pad 39A a full workout. The following day, Columbia took off at 07: 35 hrs local time, featuring in one of the most beautiful lift-offs of a Shuttle, making a direct insertion burn to 28.5° orbit. On day two, the Shuttle’s major payload on the upward journey, Syncom IV, or Leasat 5, was deployed, and Columbia sailed on towards its dramatic meeting with the LDEF. There was a serious water leak on the third day, involving the collection of two gallons of water globules.

The complicated LDEF rendezvous was completed on the fourth day, 12 January, when Columbia flew towards, over and down to the facility, with its payload bay

doors opening towards the Earth, waiting to receive. While Brandenstein deftly manoeuvred the Shuttle as it had never been manoeuvred before, Dunbar got ready with the RMS robot arm, which she was operating using a monitor showing scenes from the TV camera at its end. Brandenstein stopped all motion and, as rehearsed hundreds of times, Dunbar made the great space catch. As pilot Jim Wetherbee flew Columbia belly first, the LDEF was manoeuvred into several positions while the other mission specialists, David Low and Marsha Ivins, took close up photographs of every part, just in case the LDEF could not be safely secured in the payload bay and had to be left in space. Following the style of the mission, LDEF was berthed in the payload bay later, after 2,093 days autonomous flying in space, pitted, torn and worn. Columbia continued on its winning way, with the crew busying themselves with an array of science experiments, a range of medical experiments under the Extended-Duration Orbiter Medical Programme (EDOMP) and Dunbar getting the news that her husband (Ronald Sega) had been selected for astronaut training.

The landing on the ninth mission day was called off by a failure of one of the suite of five computers on board, and as a result, Columbia returned to Edwards Air Force Base on runway 22 at night, and after a Shuttle-record mission lasting 10 days 21 hours 0 minutes 36 seconds – the longest five-crew space flight, and with the heaviest landing weight of 103,572 kg (228,376 lb). STS-32 was probably the most complicated space flying mission and certainly the most successful and rewarding, as scientists pored over the LDEF to see how its time in space had affected its array of different materials.

Milestones

130th manned space flight 63rd US manned space flight 33rd Shuttle mission 9th flight of Columbia

Brandenstein celebrates his 47th birthday in space (17 Jan)

|

Flight Crew

SOLOVYOV, Anatoly Yakovlovich, 42, Soviet Air Force, commander, 2nd mission

Previous mission: Soyuz TM5 (1988)

BALANDIN, Aleksandr Nikolayevich, 36, civilian, flight engineer

Flight Log

What was planned as a now-standard five month residency aboard the Mir complex began at 07: 16 hrs local time at Baikonur on 11 February, when Soyuz TM9 lifted off, watched by US astronaut guests Dan Brandenstein, Paul Weitz, Ron Grabe and Jerry Ross. Docking was completed two days later and, yet again, was a manual affair, with the automatic approach malfunctioning at the last moment. The TM9 cosmonauts, Anatoly Solovyov and Aleksandr Balandin, joined Aleksandrs Viktorenko and Serebrov for the traditional handover period. The TM9 residency began officially on 19 February and was due to last until 30 July, following the 22 July launch of Soyuz TM10.

The TM9 crew were expected to receive the second large add-on module, Kristall, in April and begin an intensive programme of materials processing, so that they could return to Earth with 100 kg (221 lb) of space products to make a profit of 25 million roubles from the 80 million rouble space flight. Thus, the space flight could be seen as actually contributing to the economy and not as wasteful and extravagant as it was regarded by much of the Soviet public.

As Soyuz TM9 approached Mir, TV pictures, seen on the national news, revealed that the thermal insulation blankets around the flight cabin had become unclipped. The Soviets routinely announced that at some time during the mission the crew would have to make an unscheduled spacewalk to clip them back on. No fuss was made of the event. After settling into the routine of life aboard Mir, TM8 cosmonauts Viktorenko and Serebrov left them to it, and the routine continued with the docking of the Progress M3 supply ship on 3 March.

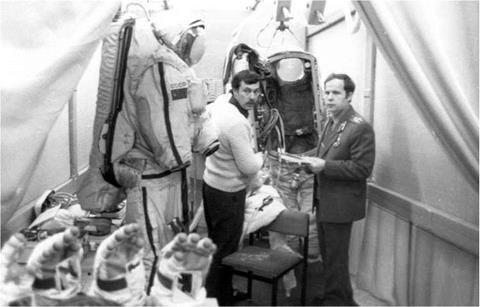

|

Solovyov (right) and Balandin reviewing EVA equipment and hardware during training |

The mission proceeded very quietly, but the scheduled launch date for Kristall passed before the Soviets announced that the new module had been delayed yet again, this time until June. The crew which had trained especially to operate Kristall would only have about two months to do so, rather than the planned four months. Progress 42, the last of the original spacecraft first launched in 1978, docked to Mir on 8 May and later in the month, the most bizarre case of inaccurate and distorted media hype of the space age occurred when Aviation Week magazine “discovered” the already three – month-old story of the unclipped insulation, leading the western press to print stories of the cosmonauts being stranded in space. If there had been any danger, the Soviets would have launched an unmanned replacement ferry immediately, rather like they did with Soyuz 34 which replaced Soyuz 32 during the Salyut 6 mission of 1979. The delayed Kristall was at last launched on 31 May but at first failed to dock when a computer fouled up during the final approach. It finally moored at Mir on 10 June.

Because of the delay to the launch of Kristall, the Soviets decided to extend the TM9 mission from 29 July to 9 August and to delay the launch of the replacement TM10 from 22 July to 1 August. On 1 July, Solovyov and Balandin made a 7 hour EVA to clip back the loose insulation on their TM9 ferry. They used the Kvant 2 airlock and while exiting, opened the outer hatch before the airlock had fully depressurised. It flew open with such a force that it almost came off its hinges. Not surprisingly, after their tortuous record-breaking EVA, scrambling over the Soyuz and successfully re-clipping only two of the three insulation panels, the cosmonauts couldn’t close the hatch properly and were forced to depressurise the rest of Kvant to gain entry to Mir. Another spacewalk, lasting three hours on 26 July, closed the hatch but did not completely seal it.

It would be left for the TM10 crew to do the necessary repairs. Its cosmonauts, the “two Gennadys”, Manakov and Strekalov, arrived on Mir on 3 August, and on 9 August as advertised, Solovyov and Balandin routinely ended their mission, making a mockery of the media hype the previous June. The mission lasted 179 days 2 hours 19 minutes.

Milestones

131st manned space flight

68th Soviet manned space flight

61st Soyuz manned mission

8th Soyuz TM manned mission

16th Soviet and 39th flight with EVA operations

Baladin celebrates his 37th birthday in space (30 Jul)