SOYUZ TM12

|

Int. Designation |

1991-034A |

|

Launched |

18 May 1991 |

|

Launch Site |

Pad 1, Site 5, Baikonur Cosmodrome, Kazakhstan |

|

Landed |

10 October 1991 (Artsebarsky on TM12); 25 March 1992 (Krikalev on TM13); 26 May 1991 (Sharman on TM11) |

|

Landing Site |

67 km southeast of Arkalyk |

|

Launch Vehicle |

R7 (11A511U2); spacecraft serial number (7K-M) 062 |

|

Duration |

144 days 15hrs 21 min 50 sec (Artsebarsky); 311 days 20 hrs 1 min 54 sec (Krikalev); 7 days 21 hrs 14min 20 sec (Sharman) |

|

Call sign |

Ozon (Ozone) |

|

Objective |

Delivery of the 9th main crew to Mir and operation of UK Juno programme by Sharman |

Flight Crew

ARTSEBARSKY, Anatoly Pavolich, 34, Soviet Air Force, commander KRIKALEV, Sergei Konstantinovich. 32, civilian, flight engineer, 2nd mission Previous mission: Soyuz TM7 (1988)

SHARMAN, Helen Patricia, 27, civilian, UK cosmonaut researcher

Flight Log

The agreement to fly a UK citizen to a Soviet space station originated in 1986, but was not signed until 1989. Financial problems dogged the project but in November 1989, four finalists were named. Sharman was named as primary candidate in February 1991, with Major Tim Mace of the British Army as her back-up. During the docking with the Mir complex, erroneous readings were produced by the rendezvous equipment. Artsebarsky had to dock manually, while Sharman operated cameras from the Descent Module and Krikalev observed the docking from the forward window in the Orbital Module. After performing a week of experiments focusing on medical tests, physical and chemical research, as well as contacting nine British schools by radio, Sharman returned to Earth with the Mir EO-8 crew on TM11. The landing on TM11 was very hard, with the capsule rolling several times and resulting in disorientation and bruising to the crew inside.

The primary objective of the ninth main Mir crew (EO-9) involved a construction programme, with up to eight EVAs planned for their five-month tour aboard the station. Their first task, however, was to relocate TM12 from the front to the aft port to permit the arrival of Progress M8. This was followed by the release of a small minisatellite, MAK-1, from the experiment airlock in the base block. MAK-1 was designed

|

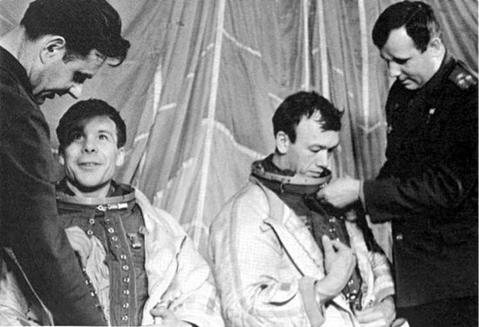

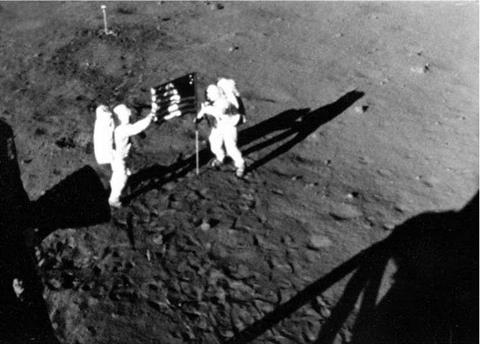

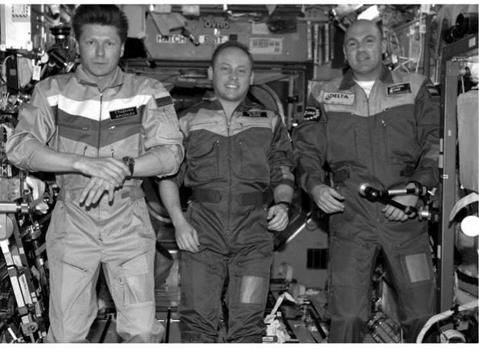

The Soyuz TM12 prime crew of Artsebarsky (left), Sharman and Krikalev |

to study Earth’s ionosphere, but a system failure rendered the satellite inoperable. The first of what turned out to be six EVAs by this crew (24 June, 4 hours 53 minutes) involved the removal and replacement of the failed Kurs approach system. EVA 2 (28 June, 3 hours 24 minutes) involved the deployment of the US-developed TREK device for studying cosmic rays. The other four EVAs (15 July, 5 hours 56 minutes; 19 July, 5 hours 28 minutes; 23 July, 5 hours 34 minutes and 27 July, 6 hours 49 minutes) focused on the construction of the Sofora girder structure. The crew deployed the Hammer and Sickle national flag of the USSR atop the girder during the sixth EVA, but Artsebarsky’s visor fogged up from his excursions during this EVA, requiring Krikalev to help him back to the hatch. The crew also continued space physics investigations, astrophysical observations, a range of technological experiments and observations of the Earth and its weather phenomena.

This five-month mission was flown at the time of the failed Soviet coup of August 1991 and the demise of the Soviet Union in the following months. Despite media reports suggesting he would be stranded alone in space, Krikalev was never “alone”. He was asked to remain on board the station when funding difficulties affected the flights of TM13 and TM14 later in the year. When the original crews of these two missions were merged into one new crew, only Alexander Volkov was qualified to remain on the station. Krikalev was asked to extend his mission until March when the next scheduled Russian resident crew would arrive. He agreed, and completed an unplanned nine-month stay in space as part of the EO-10 crew.

Milestones

141st manned space flight 71st Soviet manned space flight 64th Soyuz manned space flight 11th Soyuz TM flight 12th manned Mir mission 9th main crew

19th Soviet and 43rd flight with EVA operations 1st UK citizen (Sharman) in space 1st woman to visit Mir (Sharman)

Krikalev celebrates his 33rd birthday in space (27 Aug) Artsebarsky celebrates his 35th birthday in space (9 Sep)

STS-54

Pad 39B, Kennedy Space Center, Florida 19 January 1993 Runway 33, Kennedy Space Center, Florida OV-105 Endeavour/ET-51/SRB BI-056/SSME #1 2019; #2 2033; #3 2018 5 days 23hrs 38 min 19 sec Endeavour Deployment of TDRS-F by IUS-13; EVA operations, procedures and training exercise Flight Crew CASPER, John Howard, 48, USAF, commander, 2nd mission Previous mission: STS-36 (1990) McMONAGLE, Donald Ray, 38, USAF, pilot, 2nd mission Previous mission: STS-39 (1991) RUNCO Jr., Mario, 39, USN, mission specialist 1, 2nd mission Previous mission: STS-44 (1991) HARBAUGH, Gregory Jordan, 35, civilian, mission specialist 2, 2nd mission Previous mission: STS-39 (1991) HELMS, Susan Jane, 33, USAF, mission specialist 3 Flight Log The launch of STS-54 was delayed by just seven minutes over concerns about upper – atmospheric wind levels. The primary objective of the mission was the deployment of the sixth Tracking and Data Relay Satellite by IUS, which was accomplished on FD 1.This was the fifth successful deployment, with TDRS-B having been lost in the January 1986 Challenger accident. Also located in the payload bay was the “hitchhiker experiment”, the Diffuse X-ray Spectrometer (DXS), which was designed to collect X-ray radiation data from diffuse sources in deep space. Despite some difficulties in operating this experiment, it did return good science data. Additional experiments included one to record microgravity acceleration, and a solid surface combustion experiment that recorded the rate of flame spread and the temperature of burning filter paper. A UV Plume Imager, mounted on a free-flying satellite, observed the orbiter and obtained data on the vehicle during controlled conditions. The crew also continued the long programme of photography of the Earth surface begun in the 1960s. This was catalogued at JSC as the Earth Observation Project, and liaised with various global scientific research

efforts, allowing Shuttle crews to document specific features and phenomena of interest. The FD 5 EVA (17 Jan, 4 hours 28 minutes) was the first of a series of EVAs planned for the next three years, leading up to start of space station construction (planned at that time to be 1996). With only two missions having included EVA operations since the return to flight in 1988, there was an urgent need to develop experience, techniques and procedures on extensive EVA operations prior to constructing the space station. On STS-54, the two EVA astronauts (Harbaugh EV1 and Runco EV2) tested their ability to freely move around the payload bay, to climb into the foot restraints without using their hands, and to simulate carrying large objects in the microgravity environment. This was also useful in evaluating the possibility of rescuing an incapacitated crew member during an EVA. They also evaluated the differences and similarities in these tasks between training simulations and actual orbital operations. After the EVA, they answered detailed questions on their experiences and, following the mission’s return to Earth (which was delayed by one orbit due to ground fog at the Cape), went back into the WETF to evaluate the tasks again, for comparison with the actual EVA and to help improve future training procedures. The crew also participated in the Physics of Toys experiment during a 45-minute live TV transmission. Staff at the Museum of Natural Science helped to develop the course, which was designed to generate interest in science at schools. The toys were selected by a team of physicists. The Physics of Toys experiment was a follow-on to the Toys in Space package flown on STS 51-D in 1985. Milestones 157th manned space flight 83rd US manned space flight 26th US and 48th flight with EVA operations 53rd Shuttle mission 3rd flight of Endeavour 6th TDRS deployment mission STS-63 |

|

Int. Designation |

1995-004A |

|

Launched |

3 February 1995 |

|

Launch Site |

Pad 39B, Kennedy Space Center, Florida |

|

Landed |

11 February 1995 |

|

Landing Site |

Runway 15, Shuttle Landing Facility, KSC, Florida |

|

Launch Vehicle |

OV-103 Discovery/ET-68/SRB BI-070/SSME #1 2035; #2 2109; #3 2029 |

|

Duration |

8 days 6 hrs 28 min 15 sec |

|

Call sign |

Discovery |

|

Objective |

Mir Rendezvous (near-Mir) mission; SpaceHab 3; EVA Development Flight Test |

Flight Crew

WETHERBEE, James Donald, 42, USN, commander, 3rd mission Previous missions: STS-32 (1990); STS-52 (1992)

COLLINS, Eileen Marie, 38, USAF, pilot

HARRIS Jr., Bernard Anthony, 38, civilian, mission specialist 1, 2nd mission Previous mission: STS-55 (1993)

FOALE, Colin Michael, 38, civilian, mission specialist 2, 3rd mission Previous missions: STS-45 (1992); STS-56 (1993)

VOSS, Janice Elaine, 38, civilian, mission specialist, 2nd mission Previous mission: STS-57 (1993)

TITOV, Vladimir Georgievich, 48, Russian Air Force, Russian mission specialist 4, 3rd mission

Previous missions: Soyuz T8 (1983); Soyuz T10 launch pad abort (1983); Soyuz TM4 (1987)

Flight Log

As originally planned, Mir should have been visited by the Soviet Space Shuttle Buran but when the first Shuttle finally reached the space complex, it was an American, not a Russian one. The STS-63 mission achieved a number of milestones in space history for both the US and the Russian space programmes, and was another significant step towards cooperative efforts for the forthcoming ISS. With only a five-minute window to rendezvous with Mir, Discovery’s countdown was refined to include additional holding time at the T — 6 hour and T — 9 minute points. The 2 February launch was postponed at T — 1 day when one of the three IMUs on Discovery failed.

Starting on FD 1, a series of thruster burns brought Discovery to a rendezvous with Mir on FD 4. The approach was expected to be as close as 10 metres, but with three of the Shuttle’s 44 RCS thrusters used for small manoeuvres leaking prior to

|

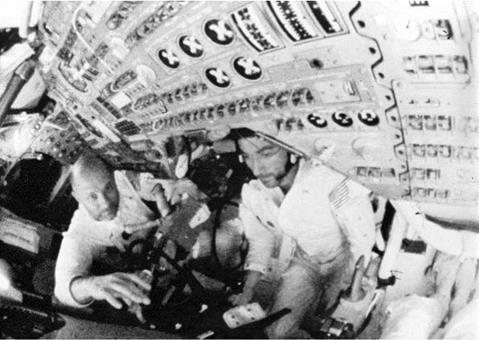

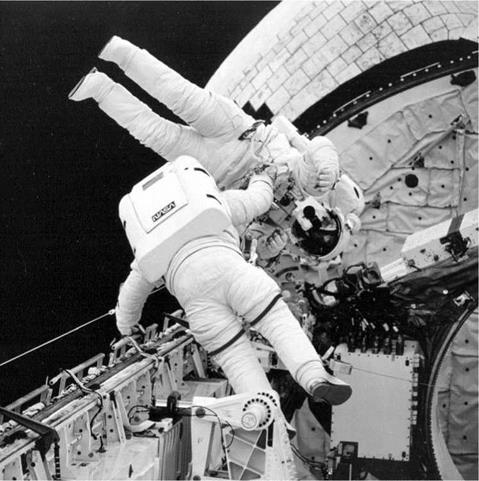

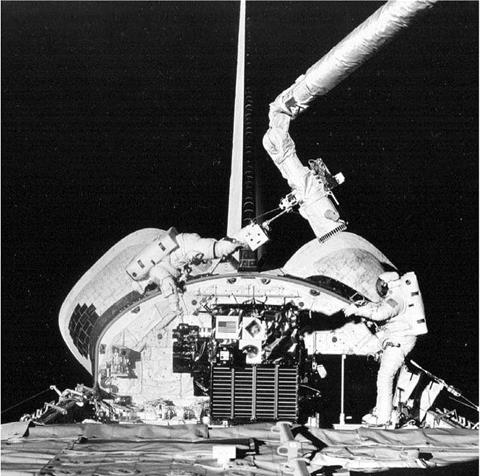

Astronaut Foale (on the RMS) attempts to grab the SPARTAN 204 as Harris looks on during the first EDFT EVA. The roof of the SpaceHab module is in foreground |

rendezvous, the Russians voiced some concerns and it took some considerable discussions and exchange of technical information to convince them that it was safe to proceed. Wetherbee brought the Shuttle to a station-keeping distance of 122 metres, then closed to about 11.2 metres with the crews excitedly talking to each other. Cosmonaut Titov, who was aboard Discovery, had spent over a year on Mir in the late 1980s and talked extensively with his colleagues on the station. This was the first time American and Russian spacecraft had been this close for almost 20 years and the next step in the schedule was the planned docking of STS-71 in June. For now, the close approach was a useful demonstration of a skill that American astronauts had not used in conjunction with another manned spacecraft since the Apollo era – proximity operations. Discovery was eventually withdrawn back to 122 metres and Wetherbee executed a one-and-a-quarter orbit loop around Mir as the astronauts conducted a detailed photographic survey of the station. On board Mir, the EO-17 crew reported no vibrations or movement of the station’s solar array panels during the manoeuvres. This was an excellent start to Shuttle-Mir operations and is often termed the near-Mir mission.

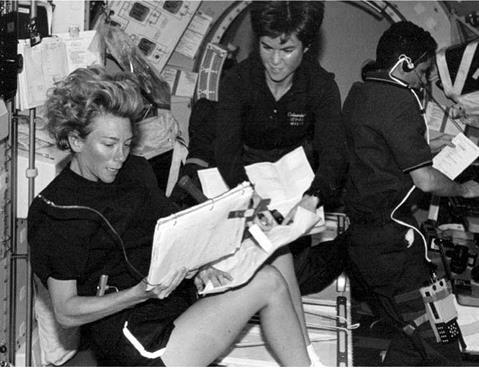

In addition to the Mir rendezvous, STS-63 featured the usual complement of middeck and payload bay secondary experiments, plus the third flight of SpaceHab. This flight of the commercially-developed augmentation module included 20 experiments, with 11 biotechnology experiments, three advanced materials development experiments, four demonstrations of technology and a pair of hardware experiments supporting acceleration technology. In past flights, crew time was taken up with caretaking the experiments but on this flight, developments in remote monitoring and data transfer reduced direct crew involvement and allowed principle investigators to monitor and control their own experiments. A new robotic device to change samples, called Charlotte, was also flown as an evaluation of automated systems that would allow the crew to focus their efforts on other areas of the flight plan. SPARTAN-204 was lifted out of the cargo bay on FD 2 by the RMS and would study the orbiter glow phenomena and firings of the jet thrusters on the Shuttle. It was later released for a 40-hour free-flight, during which time its Far UV Imaging Spectrograph studied a range of celestial targets in interstellar space.

The SPARTAN was also planned to be used during the EVA towards the end of the mission. The EVA (9 Feb, 4 hours 39 minutes) was the first in a series of EVA Development Flight Test objectives designed to prepare NASA for ISS assembly activities. Harris (EV1) and Foale (EV2) were meant to handle the 1,134kg SPARTAN payload to rehearse ISS assembly techniques for translating large masses, but both astronauts reported feeling cold while at the end of the RMS, despite modifications in their suits to keep them warm when away from the somewhat protected environment of the payload bay. One of the final objectives of STS-63 was to test the revised landing surface at the Shuttle Landing Facility. This was expected to decrease wear on the tyres and give the orbiters a better chance of landing in crosswinds, thus offering a greater range of landing opportunities at the Cape to help maintain processing schedules and to meet the launch windows of a tight manifest. Upon landing, the crew received congratulations from the cosmonauts on Mir. The once-independent US and Russian manned space programmes were beginning to merge into one international programme for ISS and this mission was an important step towards that goal.

Milestones

176th manned space flight 97th US manned space flight 67th Shuttle mission 20th flight of Discovery

31st US and 56th flight with EVA operations

1st orbiter to complete 20 missions

1st approach/fly-around with Mir by US Shuttle

1st female Shuttle pilot

2nd Russian cosmonaut on Shuttle

1st EDFT excursion

3rd SpaceHab mission

1st African American to perform EVA (Harris)

STS-94

Pad 39A, Kennedy Space Center, Florida 17 July 1997 Runway 33, Shuttle Landing Facility, KSC, Florida OV-102 Columbia/ET-86/SRB BI-088/SSME #1 2037; #2 2034; #3 2033 15 days 16hrs 34 min 4 sec Columbia Objective Material Science Laboratory 1 (Re-flight) Flight Crew HALSELL Jr., James Donald, 40, USAF, commander, 4th mission Previous missions: STS-65 (1994); STS-74 (1995); STS-83 (1997) STILL, Susan Leigh, 35, USN, pilot, 2nd mission Previous mission: STS-83 (1997) VOSS, Janice Elaine, 40, civilian, mission specialist 1, payload commander, 4th mission Previous missions: STS-57 (1993); STS-63 (1995); STS-83 (1997) GERNHARDT, Michael Landen, 40, civilian, mission specialist 2, 3rd mission Previous missions: STS-69 (1995); STS-83 (1997) THOMAS, Donald Alan, 41, civilian, mission specialist 3, 4th mission Previous missions: STS-65 (1994); STS-70 (1995); STS-83 (1997) CROUCH, Roger Keith, 57, civilian, payload specialist 1, 2nd mission Previous mission: STS-83 (1997) LINTERIS, Gregory Thomas, 39, civilian, payload specialist 2, 2nd mission Previous mission: STS-83 (1997) Flight Log The 84-day turnaround from the landing of STS-83 to the launch of the re-flight mission, designated STS-94, was a new record and an impressive demonstration of the ability and skills of the processing team. The quick turnaround was in part facilitated by servicing the MSL payloads while still in the payload bay of Columbia. The original STS-94 mission was manifested as a “flight opportunity” by Discovery in October 1998, but as no payload had been assigned to that flight, it was the first available flight number to assign the MSL administration and planning documents to. As the same vehicle, crew and payload would be flying, it was in effect a “paper change” to the flight designation, although a new ET, SRBs and different SSMEs were

assigned to support the new mission. There was a delay to the launch due to unacceptable weather around the SLF. With the crew operating the familiar Red and Blue two-shift system, 33 investigations were completed in the fields of combustion, biotechnology and materials processing. There were 25 primary investigations, four glove box investigations and four accelerometer studies on MSL-1. Some of this work involved evaluating hardware, facilities and procedures in preparation for similar hardware and research programmes that were due to be carried out on ISS. Within the combustion investigations, 144 experiments were planned, and over 200 were actually completed. The TEMPUS electromagnetic containerless processing facility completed over 120 melting cycles of zirconium at temperatures ranging between 340 and 2,000° C. In the “ignition of large fuel droplets” experiment, conducted in the glove box, only 52 test runs were planned, but the crew managed to complete 125 by the end of the mission. There were in excess of 700 crystals of various proteins grown during the 16-day mission and a record number of commands (over 35,000) were sent from the Spacelab Mission Operations Control Center at Marshall Space Flight Center to the MSL-1 experiments. On 2 July, Don Thomas reported sighting the Mir space station as it passed within 100 km of Columbia. Two days later, as America celebrated Independence Day, the crew sent messages of congratulations to the JPL Pathfinder team in California on the successful landing of the Mars Pathfinder spacecraft on the Red Planet. Three days later, the crew were informed of the successful docking of a Russian Progress (M35) re-supply vehicle with Mir and the following day, Halsell, Gernhardt and Voss used the SAREX equipment aboard Columbia to talk with Mike Foale aboard the Mir space station. On 14 July, the crew reported a minute debris impact with one of the overhead windows, a familiar occurrence which again was no cause for concern over safety. Shuttle windows are often hit by small pieces of space debris during orbital flight. Being multi-layer panels, such small impacts are highly unlikely to jeopardise the integrity of the window or the safety of the crew and vehicle. Milestones 199th manned space flight 115th US manned space flight 85th Shuttle mission 23rd flight of Columbia 1st re-flight of same vehicle, payload and crew 15th flight of Spacelab Long Module 11th EDO mission The Fifth Decade: 2001-2006

|

1993-003A 13 January 1993

1993-003A 13 January 1993

1997-032A 1 July 1997

1997-032A 1 July 1997

None – sub-orbital flight 21 July 1961

None – sub-orbital flight 21 July 1961 1969-004A (Soyuz 4)/1969-005A (Soyuz 5)

1969-004A (Soyuz 4)/1969-005A (Soyuz 5)