STS-82

|

Int. Designation |

1997-004A |

|

Launched |

11 February 1997 |

|

Launch Site |

Pad 39A, Kennedy Space Center, Florida |

|

Landed |

21 February 1997 |

|

Landing Site |

Runway 15, Shuttle Landing Facility, KSC, Florida |

|

Launch Vehicle |

OV-103 Discovery/ET-81/SRB BI-085/SSME #1 2037; |

|

#2 2040; #3 2038 |

|

|

Duration |

9 days 23 hrs 37 min 9 sec |

|

Call sign |

Discovery |

|

Objective |

2nd Hubble Servicing Mission |

Flight Crew

BOWERSOX, Kenneth Duane, 40, USN, commander, 4th mission Previous missions: STS-50 (1992); STS-61 (1993); STS-73 (1995) HOROWITZ, Scott Jay, 39, USAF, pilot, 2nd mission Previous mission: STS-75 (1996)

TANNER, Joseph Richard, 47, civilian, mission specialist 1, 2nd mission Previous mission: STS-66 (1994)

HAWLEY, Steven Alan, 45, civilian, mission specialist 2, 4th mission Previous missions: STS 41-D (1984); STS 61-C (1986); STS-31 (1990) HARBAUGH, Gregory Jordan, 39, civilian, mission specialist 3, 4th mission Previous missions: STS-39 (1991); STS-54 (1993); STS-71 (1995)

LEE, Mark Charles, 44, USAF, mission specialist 4, payload commander, 4th mission

Previous missions: STS-30 (1989); STS-47 (1992); STS-64 (1994)

SMITH, Steven Lee, 38, civilian, mission specialist 5, 2nd mission Previous mission: STS-68 (1994)

Flight Log

This was the first flight of Discovery after returning from its maintenance down period. The launch had been scheduled for 13 February but was moved up two days to give more flexibility. This mission was the second servicing mission to the Hubble Space Telescope, this time to upgrade and maintain the facility for further orbital use. It would also demonstrate the unique capability of the Shuttle to serve as a satelliteservicing vehicle, and the importance of having humans aboard to respond to unplanned activities. Four EVAs were scheduled, and a fifth was added to repair insulation material on the telescope.

Hubble was recaptured by the RMS and placed in Discovery’s payload bay on 13 February. Lee (EV1) and Smith (EV2) participated in EVAs 1, 3 and 5, while

|

|

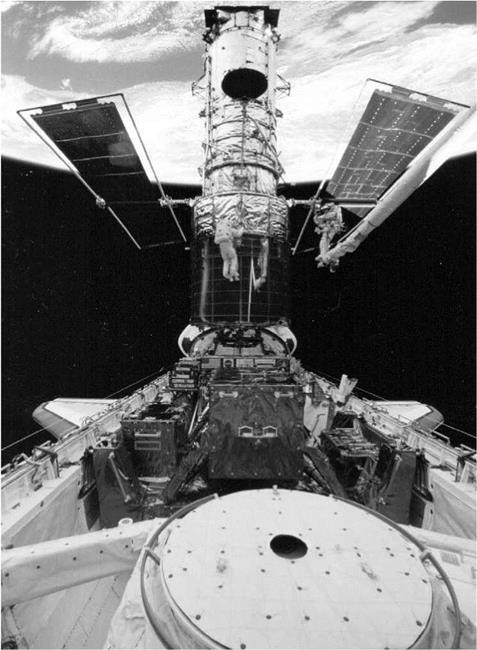

A wide-angle view of the HST in Discovery’s payload bay high over Australia during the fifth and final EVA of the STS-82 mission. Steve Smith (centre) and Mark Lee (on RMS) are conducting a survey of handrails on the telescope. In the foreground is the hatch that provides access to the airlock and crew compartment of the Shuttle

Harbaugh (EV3) and Tanner (EV4) conducted EVAs 2 and 4. When one EVA crew was outside, the other provided IV support and EVA choreography, as well as resting and preparing their own EVA equipment for their next excursion. There were over 150 tools and crew aids available to the EVA astronauts on this flight.

During the first EVA, the astronauts replaced the Goddard High Resolution Spectrograph (GHRS) and Faint Object Spectrograph (FOS) with the new Space Telescope Imaging Spectrograph (STIS) and Near-Infrared Camera and Multi-Object Spectrometer (NICMOS). The second EVA saw the replacement of the Far Guidance System (FGS) and out-of-date recorders. The astronauts also installed the Optical Control Electronics Enhancement Kit (OCE-EK). It was on this EVA that cracking and wear to the telescope’s insulation material on the Sun-facing side in the direction of orbital travel was noted. EVA 3 was used to replace the older reel-to-reel Engineering and Science Data Recorders (ESDR) with new solid state data recorders. The Data Interface Unit (DIU) was also replaced, as was one of the four Reaction Wheel Assembly Units used to generate spin momentum both to move the telescope and to keep it stable. At the end of this EVA, mission managers decided to add a fifth EVA to repair the thermal insulation damage that had been discovered earlier.

During EVA 4, the Solar Array Drive Electronics (SADE) were replaced and new covers were placed over the magnetometers. The astronauts also installed thermal blankets of multi-layered material over two areas where the insulation had degraded. This was around the light shield section of the instrument near the top of the telescope. While Harbaugh and Tanner were completing this EVA, Horowitz and Lee worked inside Discovery to fabricate new insulation blankets for the telescope from spare material carried on the mid-deck. The fifth and final EVA saw the attachment of several thermal blankets to three equipment compartments at the top of the Support System Module, which contained key data-processing, electronics and scientific instrument and telemetry packages. At the close of this final excursion outside, the astronauts had logged 33 hours 11 minutes of total EVA time.

During the time the telescope was attached to the payload bay, Discovery’s manoeuvring engines were fired several times to raise the orbit by 8 nautical miles. The telescope was released on 19 February into its highest orbit to date, of 599 km x 620 km. The landing of Discovery was on the second attempt for 21 February, after the initial opportunity was waived off due to low clouds. The next planned Hubble service missions were manifested for 1999 and 2002.

Milestones

196th manned space flight

112th US manned space flight

82nd Shuttle mission

22nd flight of Discovery

2nd HST Service Mission

35th US and 65th flight with EVA operations

Bowersox exceeds 1,000 hours in space

|

Flight Crew

HALSELL Jr., James Donald, 40, USAF, commander, 3rd mission Previous missions: STS-65 (1994); STS-74 (1995)

STILL, Susan Leigh, 35, USN, pilot

VOSS, Janice Elaine, 40, civilian, mission specialist 1, payload commander,

3rd mission

Previous missions: STS-57 (1993); STS-63 (1995)

GERNHARDT, Michael Landen, 40, civilian, mission specialist 2, 2nd mission Previous mission: STS-69 (1995)

THOMAS, Donald Alan, 41, civilian, mission specialist 3, 3rd mission Previous missions: STS-65 (1994); STS-70 (1995)

CROUCH, Roger Keith, 57, civilian PhD, payload specialist 1 LINTERIS, Gregory Thomas, 39, civilian, payload specialist 2

Flight Log

The original launch on 3 April was delayed by 24 hours on 1 April after it became necessary to add extra thermal insulation to a water coolant line in Columbia’s payload bay. There was concern that there was insufficient insulation and that the line might freeze while in orbit. A further 20.5 minute delay on launch day was caused by the need to replace the orbiter access hatch seal.

The mission was planned for sixteen days, supported by an EDO kit. However, when a sudden upward voltage trend was noted in Fuel Cell 2 shortly after reaching orbit, mission rules were implemented and meant an early termination of the flight. Though the vehicle could fly safely on two fuel cells, mission rules state that all three fuel cells need to be operating well to ensure crew safety and provide sufficient back-up capacity during re-entry and landing. Similar problems had been noted with this fuel cell during launch check-ups, but tests cleared the unit for flight. Measures to address

|

Greg Linteris (left) is seen at the Mid-deck Glove Box (MGBX) while Don Thomas works at the Expedite Processing of Experiments to Space Station (EXPRESS) rack. Despite the shortened mission the crew were able to achieve some science results |

the problem on orbit were to no avail and on 6 April, the mission management team opted to terminate the mission at the earliest point.

The crew had been able to conduct some science in the Spacelab module despite the early return. Some of the materials processing experiments and fire-related experiments were conducted, but most of the experiments on board the science laboratory had not been fully activated when the call came to shorten the mission. Shortly after landing, the mission management team indicated that a re-flight of the mission was possible despite an extremely tight manifest for the rest of the year. Halsell commented that his crew had just completed the best training session possible in order to fly – they trained in space!

NASA began to evaluate manifesting STS-83R (Re-flight) to fly after the next Shuttle-Mir docking mission (STS-84), which was scheduled for May. By 24 April, the mission had been re-designated STS-94 (the next available flight number in the manifest) and the remaining 1997 missions were adjusted to accommodate the extra flight.

This would be one of the quickest turnarounds in Shuttle history and the first time a complete crew would re-fly intact and return to orbit to complete an abbreviated mission. By using the same orbiter, configured the same way, and flying the same crew, considerable time would be saved in processing the launch.

Post-flight tests indicated that an undetermined and isolated incident had caused a slight change in the voltage in about 25 per cent of the 96 cells that comprised the fuel cell generation unit, rather than a complete cell failure as at first suspected. More monitoring would be introduced on future missions, as it was determined that Columbia could have flown its full mission without problems. In light of the Challenger accident, the question of safety was raised given the quick turnaround plan, but an independent aerospace safety advisory panel recommended that NASA was capable of quickly flying Columbia again without placing undue risks on the crew or the vehicle.

Milestones

197th manned space flight

113th US manned space flight

83rd Shuttle mission

22nd flight of Columbia

14th flight of Spacelab Long Module

3rd shortened Shuttle mission

10th EDO mission (planned)