. SOYUZ TMA2

Flight Crew

MALENCHENKO, Yuri Ivanovich, 41, Russian Air Force, ISS-7 and Soyuz commander, 3rd mission

Previous missions: Soyuz TM19 (1994); STS-101 (2000)

LU, Edward Tsang, 39, civilian, US ISS-7 science officer, 3rd mission Previous mission: STS-84 (1997); STS-101 (2000)

Flight Log

With the loss of Columbia in February 2003, it would be necessary to use the Soyuz TMA spacecraft to launch and return resident crews to the station for the time being until the Shuttle was declared operational again. Due to the limited supply capability for replenishing logistics on the station with the Shuttle fleet grounded, it was also determined that resident crews would now consist of only two persons, launched to the station every six months. The pairing would consist of one American and one Russian crew member, rotating the command position with each mission. The previously identified three-person ISS crews were reassigned as two-person teams, and the third seat was assigned to European astronauts flying short visiting missions during the exchange of crews for the time being. As the crews and launch manifest were changed and America began the investigation into the STS-107 accident, ESA announced that they had delayed the launch of their next astronaut to ISS for six months under agreement with Russia. Therefore, TMA2 would fly with only the two ISS-7 crew members aboard for six-month residency, with no planned EVAs and no other visitors.

The two crew members would be known as “caretaker” crews, able to maintain the systems of the complex, to prevent unmanned loss of control and to sustain consumables, but with limited capacity to conduct science programmes. The work programme of ISS-7 was designed not to overload the crew, as no two-person crew had resided on the station before. The ISS predecessors, Salyut and Mir, had been operated by two-person crews, but ISS was much larger and more complex. The crew

|

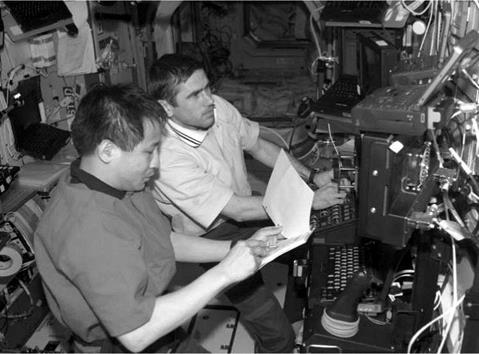

NASA ISS science officer Ed Lu (left) and station commander Yuri Malenchenko work the controls of the Canada2 RMS from inside Destiny lab |

operated what science experiments were already aboard and continued the programme of Earth observations, with Lu officially designated the NASA science officer. There were also regular maintenance and housekeeping chores to be accomplished and the crew would receive the Progress Ml-10 and M48 re-supply vehicles. Ed Lu continued the series of personal recollections of events on the station, which were posted on the web.

A demonstration of American EMU suiting was completed on 28 May, proving that the two men could suit up and remove suits without the assistance of a third person, should they be required to complete an emergency EVA. Some of the tasks were postponed due to problems with Lu’s suit that required further investigation, but it was a useful training exercise. In late June, Lu communicated by radio with former ISS-5 science officer Peggy Whitson, who was commanding a diving expedition to the NEEMO undersea habitat. This is used to develop extreme environment exploration techniques, with diving crews including NASA astronauts (both with and without flight experience) and engineers or flight controllers, to compare space flight training and flight experiences to undersea exploration.

On 10 August, “space history” was made when Malenchenko was “married” via a TV a link to his fiancee who was in Houston, Texas. The marriage had been arranged for August prior to Malenchenko being reassigned to the flight as a result of crew reshuffling after Columbia was lost. It was too late to cancel the legalities, so the wedding was authorised, with Lu acting as best man. This history-making event would be the first and last such ceremony according to officials at TsUP, and subsequent cosmonaut contracts would be amended to include a clause that no wedding would be performed while they were in space.

The ISS-8 two-person resident crew arrived at the station in October, along with ESA astronaut Pedro Duque. He would return in TMA2 with the ISS-7 crew. Their landing occurred without incident.

Milestones

238th manned space flight 95th Russian manned space flight 88th manned Soyuz mission 2nd manned Soyuz TMA mission 6th ISS Soyuz mission (6S)

1st resident caretaker ISS crew (2 person)

1st resident crew with no planned EVAs since ISS-1 Lu celebrates 40th birthday in space (1 Jul)

1st space “wedding” (10 Aug)

2003-045A

15  October 2003

October 2003

Jiuquan Satellite Launch Complex, Gobi Desert region, northwest China

16 October 2003

Dorbod Xi, Siziwang grasslands of the Gobi Desert, Inner Mongolia

CZ-2F Shenjian (Long March) (flight 5)

21 hours 26 minutes Unknown

Man-rating of the Shenzhou spacecraft for human flight; qualification and man-rating of the launch complex, launch spacecraft compatibility, orbital flight re-entry, flight control, and land-based recovery with a human passenger aboard

Flight Crew

YANG, Liwei, 38, Chinese PLA Air Force, command pilot

Flight Log

On 16 October 2003, after years of speculation and months of expectation, China became the third nation to achieve its own manned space flight capability with the launch of Yang Liwei aboard Shenzhou 5. The historic 21.5-hour flight was preceded by four unmanned test flights between November 1999 and January 2003. At the time, China had always stated that its first manned flight would occur before 2005. As the flight of Shenzhou 4 approached, it was indicated that this would be the final unmanned test flight and if successful, the first manned launch would occur before the end of 2003. Following the successful flight of Shenzhou 4, several reports revealed that the hardware was in preparation to support the first manned flight. From the team of yuhangyuans selected for the programme in 1998, a training team of three were selected, one of which would make the initial flight.

In late August 2003, the Shenzhou 5 spacecraft and its CZ-2F launch vehicle were delivered to the vehicle assembly building at the Jiuquan launch site. On 11 October, the stacked vehicle was moved to the launch pad, an operation that took 1 hour and 25 minutes. On 14 October, the training team of three yuhangyuan candidates were revealed to the Chinese press, but only after the prime pilot had been selected. The back-ups were Zhai Zhigang and Nie Haisheng, while the man destined to be the first Chinese national in space was Yang Liwei.

![]()

|

The Fifth Decade: 2001-2006

The final preparations for launch occurred in the early hours of 15 October, with Yang, suited up for the flight, travelling in a transfer bus to the launch site. Yang’s entry into the spacecraft inside the launch shroud was similar to that of the Soyuz cosmonauts, through the Orbital Module and down into the Descent Module. Unlike the Russians however, this event was filmed. In Soyuz, there is simply no room in the crew access area for a camera system to be installed and this process has thus never been seen. For American missions, the launch has always been in full public view; during the Soviet era of launches, everything was kept secret. For the first Chinese manned launch, although the event was well publicised, the launch would not be covered live.

The launch occurred at 09: 00 Beijing Time (BT — GMT + 8 hours). After two minutes, the launch escape tower ejected, no longer needed as the spacecraft could make an emergency return on its own. Sixteen seconds later, the strap-on boosters separated from the first-stage core. At 2 minutes 39 seconds into the flight, the first – stage core was shut down and separated from the vehicle as the second-stage engine and vernier engines took over, propelling the vehicle towards orbit. At 3 minutes 20 seconds, the two halves of the launch shroud used for aerodynamic purposes through the atmosphere were separated. The shut-down of the second stage occurred at 7 minutes 41 seconds Ground Elapsed Time (GET) and for the next 2 minutes 2 seconds, the vernier engines gave the Shenzhou the final nudge into orbit, before shutting down as the spacecraft separated. The launch had taken about 10 minutes. After 22 minutes in orbit, the two pairs of solar panels were deployed by ground command to generate electrical power. One pair was located on the rear Instrument Module, with the other pair on the forward Orbital Module. It had taken 12 years and one month after authorising the Project 921 programme for the first yuhangyuan to finally reach orbit.

Though an Orbital Module was present, it was announced for this flight that Yang would remain in the DM. His flight programme included the operation of a set of instruments and monitoring of space systems and functions. The spacecraft operated primarily on pre-set programmes with little input from the pilot. Tests of the communications system were combined with TV views from inside the spacecraft and outside the window. The flight duration was announced as only one day for this first manned test, but included three meals and two rest periods for the yuhangyuan. Attached to Yang’s body were medical sensors which recorded his condition and transmitted the data to a medical team on Earth. The primary purpose of this mission was to man-rate the spacecraft and system, so extensive operations would wait for later missions. The next important stage was to get Yang home.

On 16 October, following his second rest period, preparations for re-entry and landing began during the fourteenth orbit of the spacecraft. At 05:04 a. m. bt, the command for retrofire to initiate the return to Earth programme was issued from a tracking ship located in the South Atlantic Ocean. About 332 minutes later the OM separated from the spacecraft and continued in orbital flight. Two minutes later, retro – rockets on the spacecraft fired, bringing the spacecraft out of orbit. The Instrument Module was separated about 21 minutes later, as the DM containing Yang plummeted to Earth. Following re-entry, the drogue parachute was deployed 11 minutes after the separation of the modules. The main parachute was deployed five minutes after the drogue and 2 minutes after the heat shield separated from the base of the vehicle. Seven minutes later, at 06: 23 a. m. bt, the Descent Module of Shenzhou 5 landed safely after a flight of 21 hours 26 minutes.

Yang was taken back to Beijing for medical examination and mission debriefings. Now a national hero, from November he began a programme of public appearances as a major personality and the face of China’s manned space programme. While Yang took the Chinese space programme to the public, behind the scenes work continued both for the next flight and also with the OM of Shenzhou 5. The OM, unlike that of Soyuz, was capable of independent manoeuvrable flight for some months, and Shenzhou 5’s OM was packed with instruments and equipment that were tested after the yuhangyuan had returned to Earth, for about six months. These modules are expected to be of significance on future flights in the series, and are linked to the expected Chinese national space station programme.

Milestones

239th manned space flight

1st Chinese manned space flight

1st manned flight of CZ-2F launch vehicle

3rd nation to develop independent manned orbital flight

5th flight of Shenzhou spacecraft

1st manned flight of Shenzhou