MOONSHIP

Project Apollo, which brought about the deaths of Grissom, White and Chaffee and which also enabled the steps of Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin on the Moon, was born very soon after NASA’s own creation late in 1958. At that time, it was expected that exploration of the Solar System would be one arena in which the abilities of men, rather than machines, would be required. A fundamental obstacle, however, was the distinct absence of large boosters capable of fulfilling such roles and in mid-December of that year, newly installed Administrator Keith Glennan listened as Wernher von Braun, Ernst Stuhliner and Heinz Koelle presented the capabilities of existing hardware and stressed the need for a new ‘family’ of rockets. Landing men on the Moon, for the first time, was explicitly discussed as a longterm objective and, indeed, Koelle suggested a preliminary timeframe for achieving this as early as 1967.

Von Braun’s vision for the new family of rockets was that, first and foremost, their engines should be arranged in a ‘cluster’ formation, directly carrying an aviation concept into the field of spacegoing rocketry. The famed missile designer also discussed propellants and the idea of employing different combinations for different stages… then broached the subject of precisely how such enormous boosters could deliver a manned payload to the lunar surface. Von Braun had five methods in mind: one involving a ‘direct ascent’ from Earth to the Moon, the other four involving some sort of rendezvous and docking of vehicles in space. In whatever form the mission took, the rocket would need to be enormous, comprising, he said, ‘‘a seven-stage vehicle’’ weighing ‘‘no less than 6.1 million kg’’. Alternatively, he suggested flying a number of smaller rockets to rendezvous in Earth orbit and assemble a 200,000 kg lunar vehicle, which could then depart for the Moon. Aside from the immense practical problems of building and executing such a plan were the very real unknowns, Stuhlinger added, of how men and machines could operate in a weightless environment, with concerns of temperature, radiation, micrometeorites and corrosion an ever-present hazard.

Glennan’s focus at the time was, of course, Project Mercury, although in testimony before Congress early in 1959 he and his deputy, Hugh Dryden, admitted that there was ‘‘a good chance that within ten years’’ a circumnavigation of the Moon might be achieved, although not a landing, and that similar projects may be underway in connection with Venus or Mars. In support of NASA’s long-term aims, Glennan requested funding to begin developing the cornerstone for such epic ventures – the booster itself – and presented President Dwight Eisenhower with a report on four optional ‘national space vehicle programmes’: Vega, Centaur, Saturn and Nova. Although the first and last of these scarcely left the drawing board, the others would receive developmental funding and von Braun’s team, which had championed a rocket known as the Juno V, gained backing to develop it further under the new name ‘Saturn’.

In April 1959, Harry Goett, later to become director of NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland, was called upon to lead a research steering committee for manned space exploration. The major conclusions of his panel were that, after Project Mercury had sent a man into orbit, the agency’s goals should encompass manoeuvring in space, establishing a long-term manned laboratory, conducting a lunar reconnaissance and landing and eventually surveying Mars or Venus. ‘‘A primary reason,’’ remarked Goett of the choice of the Moon as a major

target, “was the fact that it represented a truly end objective which was self-justifying and did not have to be supported on the basis that it led to a subsequent more useful end.”

Elsewhere, efforts to begin developing the Saturn were gathering pace. Its challenges, though, were both huge and staggering, with propellant weights alone for a direct-ascent rocket producing a vehicle of formidable scale; indeed, even the prospects for constructing a lunar spacecraft in Earth orbit would require more than a dozen ‘smaller’ launches and the added complexity of rendezvous, docking and assembly operations. At this early stage, the problems of being able to store cryogenics for long periods in space, to have a throttleable lunar-landing engine and takeoff engine with storable propellants and auxiliary power systems were first identified.

Unfortunately, midway through Dwight Eisenhower’s second term in office, and with the emphasis of his administration on balancing the budget ‘‘come hell or high water’’, it proved impossible for Glennan to formally commit NASA to a long-term lunar effort. Instead, small groups at the agency’s field centres began springing up, including one within the Space Task Group, which considered a second-generation manned vehicle capable of re-entering the atmosphere at speeds almost as great as those needed to escape Earth’s gravitational pull. ‘‘The group was clearly planning a lunar spacecraft,” wrote Courtney Brooks, James Grimwood and Loyd Swenson, and by the autumn of 1959 sketches of a lenticular re-entry vehicle had emerged and crystallised to such a point that its designers even applied for it to be patented.

Early January of the following year finally brought approval from Eisenhower for NASA to accelerate development of von Braun’s Saturn and offered the first hint of political support for manned space efforts beyond Project Mercury. Within weeks, Glennan’s request to Abe Silverstein, director of the Office of Space Flight Programs, to encourage advanced design teams at each NASA field centre and within the aerospace industry began to bear fruit: von Braun’s team proposed a Saturn-based lunar exploration design and J. R. Clark of Vought Astronautics offered a brochure entitled ‘A Manned Modular Multi-Purpose Space Vehicle’. At this point, of course, Project Mercury had yet to accomplish its first manned mission; however, regardless of their limited chances of receiving presidential or congressional approval, the proposals continued.

Other efforts focused on exactly how the spacecraft and other hardware could be delivered to the lunar surface in the most economical way. In May 1960, NASA’s Langley Research Center sponsored a two-day conference on rendezvous, with several techniques discussed, although it was recognised that they would be unlikely to bear fruit until the agency secured funding for a flight test programme.

It was at around this time that the decision was made over naming the spacecraft which would bring about the most audacious engineering and scientific triumph in the history of mankind. The name ‘Apollo’, formally conferred upon the programme on 28 July 1960 by Hugh Dry den, would honour the Greek god of music, prophecy, medicine, light and – perhaps above all – progress. ‘‘I thought the image of the god Apollo riding his chariot across the Sun,’’ wrote Abe Silverstein, who had consulted a book on mythology to come up with the name, ‘‘gave the best representation of the grand scale of the proposed programme.’’

The scope of Apollo, Bob Gilruth and others revealed to more than 1,300 governmental, scientific and industry attendees at a planning session in August, was for a series of Earth-orbital and circumlunar expeditions as a prelude for the first manned landing on the Moon. Guidelines for the design of the spacecraft would be fourfold: it would need to be compatible with the Saturn booster under development by von Braun’s team, it had to be able to support a crew of three men for a period of up to a fortnight and it needed to encompass the lunar or Earth-orbital needs of the project, perhaps in conjunction with a long-term space station. By the end of October, three $250,000 contracts were awarded to teams led by Convair, General Electric and the Martin Company for initial studies.

In spite of this apparent brightening of the lunar project’s chances, Glennan himself remained unconvinced that Apollo was ready to move beyond the feasibility stage and felt a final decision would have to await the arrival of the new president in January 1961. By this point, Glennan was estimating Apollo to cost around $15 billion and felt that the Kennedy administration needed to spell out, clearly, and with no ambiguity, its precise reasons for pursuing the lunar goal, be they for international prestige or scientific advancement. At around the same time, Hugh Dryden and Bob Seamans directed George Low to head a Manned Lunar Landing Task Group, detailed to draft plans for a Moon programme, utilising either direct – ascent or rendezvous, within cost and schedule guidelines, for use in budget presentations before Congress. When Low submitted his report in early Lebruary, he assured Seamans that no major technological barriers stood in the way and that, assuming continued funding of both the Saturn and Apollo, a manned lunar landing should be achievable between 1968-70.

Moreover, Low’s committee was considerably more optimistic than Glennan in terms of cost estimates: they envisaged spending to peak around 1966 and total some seven billion dollars, reasoning that by that time the Saturn and larger Nova-type boosters would have been built and an Earth-circling space station would probably be in existence. It stressed, however, that manned landings would require a launch vehicle capable of lifting between 27,200 and 36,300 kg of payload; the existing conceptual design, dubbed the ‘Saturn C-2’, could boost no more than 8,000 kg towards the Moon. Low’s group advised either that several C-2s needed to be refuelled in space or an entirely new and more powerful booster awaited creation. Both approaches seemed realistic, the committee concluded, with Earth-orbital rendezvous probably the quickest option, yet still requiring the technologies and techniques to refuel in space.

Of pivotal importance in the subsequent direction of Apollo was the new president, John Litzgerald Kennedy, who had already appointed a group before his inauguration to assess the perceived American-Soviet ‘missile gap’ and investigate ways in which the United States could pull ahead technologically. The group was headed by Jerome Wiesner of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology – later to become Kennedy’s science advisor – and it advocated, among other points, that NASA’s goals needed to be both redefined and sharpened. Another key figure, and long-time ally of NASA, was Vice-President Lyndon Johnson, who pushed strongly to appoint James Webb, a man with immense experience in government, industry and public service, to lead NASA. On 30 January 1961, Webb’s appointment as the agency’s second administrator was authorised by Kennedy.

It was Webb who would guide NASA through the genesis of Apollo; indeed, his departure from the agency would come only days before the project’s first manned launch in October 1968. His importance to America’s space heritage and the respect in which he continues to be held will be recognised, just a few years from now, by the launch of the multi-billion-dollar James Webb Space Telescope (JWST), successor to Hubble. Yet Webb’s background was hardly scientific or in any way related to space exploration: a lawyer by profession, he directed the Bureau of the Budget and served as Undersecretary of State for the Truman administration, but throughout the Sixties he would prove NASA’s staunchest and most fierce champion.

Also championing the agency’s corner was President Kennedy himself, who, only weeks before Yuri Gagarin’s flight, raised its budget by $125 million above the $1.1 billion appropriations cap recommended by Eisenhower. Much of this increase was funnelled into the Saturn C-2 development effort and, specifically, its giant F-1 engine. Built by Rocketdyne, the F-1 – fed by a refined form of kerosene, known as ‘Rocket Propellant-1’ (RP-1), together with liquid oxygen – remains the most powerful single-nozzled liquid engine ever used in service. Although it experienced severe teething troubles during its development, particularly ‘combustion instability’, it would prove impeccably reliable and the cornerstone to a lunar landing capability.

By this time, Convair, General Electric and the Martin Company had submitted their initial responses to NASA, none of which overly impressed the agency’s auditors; indeed, recounted Max Faget, all three had stuck rigidly with the same shape as the Mercury capsule. Some theoreticians had already predicted that a Mercury-type design would be unsuitable for Apollo’s greater re-entry speeds and Space Task Group chief design assistant Caldwell Johnson had begun investigating the advantages of a conical, blunt-bodied command module.

Early in May 1961, after more adjustments and rework, the contractors offered their final proposals to NASA. Convair envisaged a three-component Apollo system, its command module nestled within a large ‘mission module’. Notably, it would return to Earth by means of glidesail parachute and develop techniques of rendezvous, docking, artificial gravity, manoeuvrability and eventual lunar landings. General Electric offered a semi-ballistic blunt-bodied re-entry vehicle, with an innovative cocoon-like wrapping to provide secondary pressure protection in case of cabin leaks or micrometeoroid punctures. Martin, lastly, proposed the most ambitious design of all. Conical in shape, its Apollo was remarkably similar to the design ultimately adopted, although it featured a pressurised shell of semi – monocoque aluminium alloy coated with a composite heat shield of superalloy and a charring ablator. Its three-man crew would sit in an unusual arrangement, with two abreast and the third behind, in a set of couches which could rotate to better absorb the G loads of re-entry and enable better egress.

All three contractors spent significantly more than the $250,000 assigned by NASA, with Martin’s study topping three million dollars, requiring the work of 300 engineers and specialists and taking six months to complete. In their seminal work on the development of Project Apollo, Brooks, Grimwood and Swenson pointed out that, had times been less fortunate, NASA may have been obliged to spend months evaluating the contractors’ reports before making a decision. However, it was at this time that Yuri Gagarin rocketed into orbit and John Kennedy pressed Lyndon Johnson to find out how the United States could beat the Russians in space. On 25 May 1961, before a joint session of Congress, he made the lunar goal official… and public.

In the wake of Kennedy’s speech, one of the key areas into which the increased funding would be channelled was a new booster idea called ‘Nova’; this was considered crucial to achieving a lunar landing by the direct-ascent method. At this stage, although NASA was ‘‘studying’’ orbital rendezvous as an alternative to direct – ascent, Hugh Dryden explained that ‘‘we do not believe… that we could rely on [it]’’. More money and increased urgency for Apollo was not necessarily a good thing: both Webb and Dryden felt that decisions over direct-ascent or orbital rendezvous and liquid or solid propellants would have been better made two years further down the line.

Nonetheless, rendezvous as an option was steadily coming to the fore, with a realisation that it could provide a more attractive alternative to the need for enormous and unwieldy boosters, instead allowing NASA to use two or three advanced Saturns with engines that were already under development. Although Earth-orbital rendezvous was considered safer, a lunar-orbit option would require less propellant and could be done with just one of von Braun’s uprated Saturn ‘C-3’ rockets.

The Apollo spacecraft which would fly missions to the Moon was also taking shape. Max Faget, the lead designer of the Space Task Group, set the diameter of its base at 4.3 m and rounded its edges to fit the Saturn for a series of test flights. These rounded edges also simplified the design of an ablative heat shield which would be wrapped around the entire command module. Encapsulating the spacecraft in this way provided additional protection against space radiation, although on the downside it entailed a weight penalty. Others, including George Low, saw merits in both blunt-bodied and lifting-body configurations and suggested that both should be developed in tandem. Most within the Space Task Group, however, felt that a blunt body was the best option.

Notwithstanding these issues, in August 1961 NASA awarded its first Apollo contract to the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, directing it to develop a guidance, navigation and control system for the lunar spacecraft. Two months later, five aerospace giants vied to be Apollo’s prime contractor, with the Martin Company ranked highest in terms of technical approach and a very close second in technical qualification and business management. In second place was North American Aviation, whom the NASA selection board recommended as the most desirable alternative. On 29 November 1961, word quickly leaked out to Martin that its scores had won the contest to build Apollo, but proved premature; the following day, it was announced by Webb, Dryden and Seamans that North American would be the prime contractor, in light, it seemed, of their long-term association with NASA and NACA and their spaceflight experience. The choice of North American, whose fees were also 30 per cent lower than Martin, would in many minds return to haunt NASA in years to come.

Rumour quickly abounded that it was politics, and not technical competency, which had won North American the mammoth contract. Astronaut Wally Schirra would recount that he felt the decision was made because companies in California had yet to receive their fair share of the space business, while others pointed to the company’s lobbyist Fred Black, who had developed a close relationship with Capitol Hill insider Bobby Gene Baker, a protege of Vice-President Lyndon Johnson.

As North American and NASA hammered out their contractual details, the nature of Apollo’s launch vehicle remained unclear, as, indeed, was its means of reaching the Moon. It was likely that the production of large boosters capable of accomplishing a direct-ascent mission would take far longer than the development of smaller vehicles. The attractions of rendezvous were also becoming clearer as a means of meeting Kennedy’s end-of-the-decade deadline. At around this time, Bob Gilruth wrote that “rendezvous schemes may be used as a crutch to achieve early planned dates for launch vehicle availability and to avoid the difficulty of developing a reliable Nova-class launch vehicle’’.

As the debate over the launch vehicle continued, it was recognised that, in whatever form it took, it would be enormous and would demand a correspondingly enormous launch complex. Under consideration were Merritt Island, north of Cape Canaveral, together with Mayaguana in the Bahamas, Christmas Island, Hawaii, White Sands in New Mexico and others. Only White Sands and Merritt Island proved sufficiently economically competitive, flexible and safe to undergo further study. The final choice: a 323 km2 area of land on Merritt Island for a site later to become known (after the assassination of President John Kennedy) as the Kennedy Space Center. One of the most iconic structures to be built here in the mid-Sixties, and associated forever with the lunar effort, was the gigantic Vehicle (originally ‘Vertical’) Assembly Building (VAB), used to erect and test the Saturn rockets. Standing 160 m tall, 218 m long and 158 m wide, it covered 32,400 m2 and to this day remains the world’s largest single-story building.

Elsewhere, a site near Michoud in Louisiana was picked for the Chrysler Corporation and Boeing to assemble the first stages of the Saturn C-1 and subsequent variants. In October 1961, NASA purchased 54 km2 in south-west Mississippi and obtained easement rights over another 518 km2 in Mississippi and Louisiana for a static test-firing site for the large booster, prompting around a hundred families, including the entire community of Gainsville, to sell up and relocate. It was around the same time that the decision to move the Space Task Group – now superseded by the Manned Spacecraft Center – from Virginia to Houston, Texas, was made.

On the morning of 27 October 1961, shortly after 10:06 am, the maiden mission in support of Apollo got underway with the test of the Saturn 1 (originally C-1) rocket from Pad 34 at Cape Canaveral. Although the vehicle was laden with dummy upper stages, filled with water, its performance was satisfactory, but its 590,000 kg of thrust was woefully insufficient to send men to the Moon and back. Still, it marked the first of ten Saturn 1s launched, which, by the time of its last flight in July 1965, had carried a ‘boilerplate’ command and service module into orbit. Most engineers envisaged the lunargoing Saturn would need at least four or even five F-1 engines in its first stage. This would permit an Earth-orbit or lunar-orbit rendezvous mode to deliver a payload to the Moon’s surface. Despite continuing interest in a large, direct-ascent Nova, employing as many as eight F-1s, the decision was taken on 21 December to proceed with a rocket known as the Saturn C-5 (later the Saturn V), capable of supporting both Earth-orbital and lunar-orbital rendezvous missions.

However, direct ascent was still considered by many as the safest and most natural means of travelling to the Moon, sidestepping the dangers of finding and docking with other vehicles in space. Yet procedures for exactly how a lander might be brought onto the lunar surface remained sketchy, with some suggesting the bug-like spacecraft touching down vertically on deployable legs or horizontally on skids. An Air Force-funded study, begun in 1958 and called ‘Lunex’, had already addressed a direct-ascent method of reaching the Moon. However, Wernher von Braun doubted it was possible to build a rocket large enough to accomplish such a mission and favoured rendezvous with smaller vehicles. Before coming to NASA, von Braun’s team had proposed a mission known as ‘Project Horizon’, which justified the need for a lunar base for military, political and, lastly, scientific purposes. He felt that only Saturn was powerful enough to complete such a mission and one of his conditions upon joining NASA was that its development should continue.

Against this backdrop came the appearance of the lunar-orbital rendezvous plan, whereby a craft would descend to the Moon’s surface and, after completing its mission, return to rendezvous with a ‘mother ship’. The landing crew would then transfer to the orbiting mother ship and return to Earth. Since 1959, in fact, this idea had been recognised as the best technique to reduce the total weight of the spacecraft. Many within NASA, however, were terrified by the prospect of attempting rendezvous so far from home. Proponents, on the other hand, considered it relatively simple, with no concerns about weather or air friction, lower fuel requirements and no need for a monster Nova rocket. ft was NASA engineer John Houbolt who finally convinced Bob Seamans to place it on an equal footing with direct ascent and Earth-orbital rendezvous when a decision came to be made. By July 1962, the decision had been made: lunar-orbital rendezvous would be adopted, employing a separate lander in addition to the command ship.

At the same time, the first steps to actually design the lander got underway, with early plans ranging from short-stay missions involving one man for a few hours to seven-day expeditions with crews of two. One design took the form of an open, Buck Rogers-like ‘scooter’ with landing legs, which the fully-suited astronaut would manoeuvre onto the surface. As these plans crystallised, the paucity of knowledge of the lunar surface material, and the effect of exhaust gases on its rocks and dust, made it imperative that astronauts could ‘hover’, brake their spacecraft and select an appropriate landing spot.

North American, which had already been awarded the contract to build the command and service modules, strongly opposed the lunar-orbital rendezvous mode, partly because it wanted its spacecraft to perform the landing. (fndeed, in August 1962, cartoons adorned its factory walls, depicting a somewhat disgruntled Man in the Moon looking suspiciously at an orbiting command and service module and declaring ‘‘Don’t bug me, man!’’) With this in mind, North American made a strong bid to build the lander, which NASA rejected on the basis that the company already had its hands full with the development of the main spacecraft. By September 1962, 11 companies had submitted proposals to build the lander and in November the Grumman Aircraft Engineering Corporation of Bethpage, New York, was chosen for the $388 million contract. Although each bidder was judged technically and managerially capable, Grumman had spacious design and manufacturing areas, together with clean-room facilities to assemble and test the lander.

The decision to proceed with lunar-orbital rendezvous eliminated the requirement for the Apollo command module to land on the Moon, but created a new problem: the need for a form of docking apparatus by which it could link up with Grumman’s lander. The need was quickly identified for a series of Earth-orbital missions to demonstrate and qualify the command module’s systems before committing them to lunar sorties; the result was the Block 1 and 2 variants, the second of which provided the docking hardware and means of getting to the Moon. By mid-1963, North American had begun work on an extendable probe atop the command module, which would fit into a dish-shaped drogue on the lunar lander.

As the design of the command module moved through Block 1 and 2 variants, so the lunar module itself was changing into its final form: a two-part, spider-like ‘bug’ which would deliver astronauts to the Moon’s surface and back into orbit. Its fourlegged descent stage would be equipped with the world’s first-ever throttleable rocket engine, whilst the ascent stage, housing the pressurised cabin, would have a fixed – thrust engine to boost the crew back into lunar orbit. The organic appearance of the lunar module produced something which Brooks, Grimwood and Swenson described as ‘‘embodying no concessions to aesthetic appeal. . . ungainly looking, if not downright ugly’’. Operating within Earth’s atmosphere, obviously, would be unnecessary and aerodynamic streamlining was ignored by the Grumman designers. However, when the time came for the ascent stage to liftoff from the lunar surface, its exhaust in the confined space of the inter-stage structures – ‘fire-in-the-hole’ – could produce untoward effects, perhaps tipping the vehicle over. Clearly, many problems remained to be solved.

Shape-wise, the ascent stage was originally spherical, much like that of a helicopter, with four large windows for the crew to see forward and ‘down’. This design was ultimately discarded when it became clear that the windows would need extremely thick panes and strengthening of the surrounding structure. Two smaller windows were chosen instead, but the need for visibility remained very real, eliminating the spherical cabin design in favour of a cylindrical one with a flat forward bulkhead cut away at various planar angles. The windows became small, flat, triangular panels, canted ‘downwards’ so that the crew would have the best possible view of the landing site.

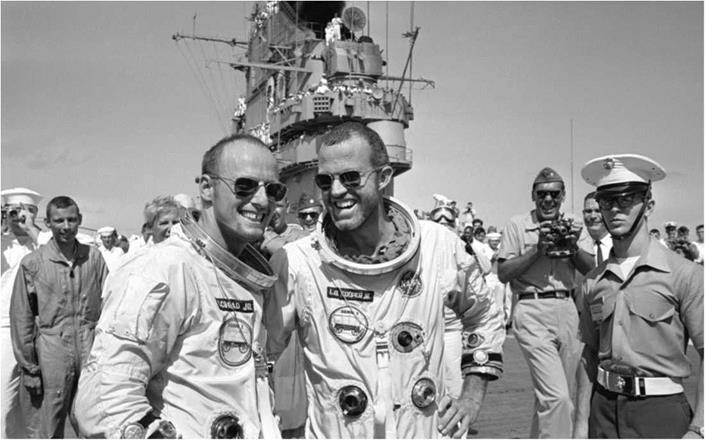

Changing from a spherical to a cylindrical cabin, though, meant that Grumman’s engineers could not easily weld the structure. By May 1964, they had decided to weld areas of critical structural loads, but rivets would be employed where this was impractical. The interior of the 4,930 kg ascent stage cabin, with a volume of 60 m3, made it the largest American spacecraft yet built and NASA pressed Grumman to make its instruments as similar to those in the command module as possible. As it evolved, the astronauts became an integral part of it, with Pete Conrad working on the design perhaps more so than anyone else. He was instrumental in implementing electroluminescent lighting inside the lunar module, as well as the command module, reducing weight and power demands.

Another crucial change in the design of the lunar module was the removal of seats, which were seen as too heavy and restrictive in view of the fact that the astronauts would be clad in bulky space suits. Bar stools and metal cage-like structures were considered, but the brevity of the lunar module’s flight and moderate G loads eventually rendered them totally unnecessary. Moreover, standing astronauts would have a better view through the windows and the eliminated worry about knee room meant that the cabin could be reduced in size. Instead of seats, restraints would be added to hold the astronauts in place and prevent them from being jostled around during landing.

The hatch, through which the astronauts would exit and re-enter from the lunar surface, was changed from circular to square to make it easier for their pressurised suits and backpacks to fit through. At the base of the 10,334 kg descent stage were five legs, later reduced to four as part of a weight-versus-strength trade-off, and 91 cm footpads with frangible probes to detect surface impact. Keeping the lander’s weight down was of pivotal importance, to such an extent that NASA paid Grumman $20,000 for every kilogram they could shave off. Even the weight of the astronauts helped determine which of them would fly the lunar module and which would not.

Inside the third stage of the Saturn V launch vehicle, the lander’s legs would be folded against the structure of the descent stage and extended in space. In addition to its ascent and descent engines, the lunar module possessed 16 small attitude-control thrusters, clustered in quads, pointing upwards, downwards and sideways around the ascent stage for increased manoeuvrability. The ascent engine, built by Bell, was a key component which simply had to work to get the astronauts away from the lunar surface; as a result, it was the least complicated device, with a pressure-fed fuel system employing hypergolic propellants. The descent engine was more challenging, since it had to be throttleable: Rocketdyne, its builder, used helium injection into the propellant flow to decrease thrust while maintaining the same flow rate.

As the command, service and lunar modules took shape, the launch vehicles for the Earth-orbital (Saturn 1B) and lunar (Saturn V) missions also approached completion. The two-stage Saturn 1B – Gus Grissom and Wally Schirra’s “big maumoo’’ – underwent its first test on 26 February 1966 and also marked the first ‘real’ flight of a ‘production’ Apollo command and service module. The rocket’s S-IB stage had arrived at Cape Kennedy in mid-August of the previous year, followed by the S-IVB a month later. By the end of October, the rocket’s instrument unit and the command and service module for the mission, designated ‘Apollo-Saturn 201’ (AS – 201), were in Florida. After numerous delays, including lower-than-allowable pressures in the S-IVB, the flight got underway at 11:12 am. The S-IB carried the Saturn to an altitude of 57 km, whereupon the S-IVB took over and boosted AS-201 to an altitude of 425 km.

After raising its own apogee to 488 km, the command and service module’s SPS engine was ignited to accelerate its return to Earth. Splashdown came at 11:49 am, half an hour after launch, and the undamaged spacecraft was hauled aboard the recovery vessel Boxer. Despite problems, AS-201 proved that the Apollo spacecraft was structurally sound and that its heat shield could survive a high-speed re-entry. However, its SPS had not performed as well as expected; firing, but only operating correctly for about 80 seconds, after which its pressure fell by 30 per cent due to helium ingestion into its oxidiser chamber. Managers, obviously, did not want such an event to occur during a return from the Moon. The SPS problem had to be rectified. Further, the effects of microgravity on the propellants in the S-IVB, which would be needed to perform the translunar injection burn, needed to be better understood.

Consequently, a decision was taken to reverse the plan of unmanned Saturn 1B launches for the remainder of the year. The six-hour AS-203 mission, not planned to carry a command and service module, was shifted ahead of AS-202 and launched on 5 July. It satisfactorily demonstrated that the S-IVB’s single J-2 engine could indeed restart in space and that the propellants behaved exactly as predited. Seven weeks later came AS-202, during which the SPS was fired four times without incident, demonstrating its quick-restart capabilities, and the heat shield was tested. Its 90- minute mission cleared the way for Apollo 1, still internally dubbed ‘AS-204’, at the end of the year.