“NOTHING SPECIAL”

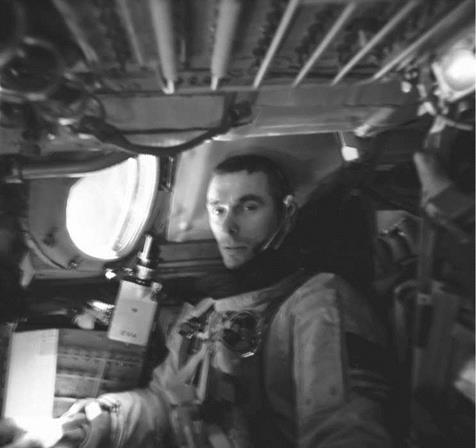

Deke Slayton and others have freely admitted that they were forced to rethink the practicalities of EVA in the seven-week interval between Geminis IX-A and X. Fortunately, the latter mission would star as its spacewalker a man who, perhaps more so than any other astronaut, knew the G4C pressure suit literally inside out. Michael Collins, who described himself as “nothing special’’, “lazy” and “frequently ineffectual”, would later gain eternal fame as ‘the other one’ on the Apollo 11 crew.

Before that, as John Young’s pilot on Gemini X, he would become the first man to make two extravehicular activities, the first man to physically touch another vehicle in space… and, alas, the first spacewalker to bring home absolutely no photographic record of his achievement.

Slayton saw Young and Collins as a perfect team. Both were obsessive hard – workers, but in contrast to Young’s reserved and publicity-shy nature, the gregarious Collins was “smooth and articulate”. Prior to his selection in October 1963, to improve this smoothness, the Air Force sent its astronaut applicants to ‘charm school’, in which Collins learned more social skills essential for spacefarers: wearing knee-length socks ‘‘that go on forever’’, abhorring hairy legs and needing to hold hands on hips in a particular way ‘‘because people you don’t want to talk about hold ‘em the other way!’’

With a father, uncle and elder brother who would all rise through the ranks to become generals, it was obvious that Collins would follow in their military footsteps. He entered the world in Rome on 31 October 1930, becoming the first American astronaut born outside the United States, and throughout his childhood was often on the move: from Italy to Oklahoma, to Governor’s Island in Upper New York Bay, to Maryland, to Ohio, to Puerto Rico and to Virginia. Whilst in Puerto Rico, Collins took his first ride in a twin-engined Grumman Widgeon, although he would admit that as graduation from West Point neared in 1952, his ‘‘love affair with the airplane had been neither all-consuming nor constant’’.

Nonetheless, he graduated from the Military Academy in the same class as fellow astronaut-in-waiting Ed White and his eventual choice of the Air Force as his parent service was based on two factors. The first was sheer wonder over where aeronautical research would lead in years to come. . . whilst the second was simply to avoid accusations of nepotism, ‘‘real or imagined’’, since his uncle happened to be the Army’s chief of staff at the time! As a cadet, Collins completed initial flight training in Mississippi aboard T-6 Texans, before moving on to jets at Nellis Air Force Base in Nevada, flying the F-86 Sabre.

Nuclear-weapons-delivery training followed at George Air Force Base in California, as part of the 21st Fighter-Bomber Wing, and Collins transferred with the detachment to Chaumont-Semoutiers Air Base in France in 1954. Two years later, whilst participating in a NATO exercise, he was forced to eject from his F-86 when a fire erupted behind his cockpit. He met Pat Finnegan in the officers’ mess and, despite their differing religious beliefs – she being a staunch Roman Catholic, he a nominal Episcopalian – the couple married in 1957.

Subsequent work as an aircraft maintenance officer, during which ‘‘dismal’’ time he trained mechanics, was followed by a successful application to join the Experimental Flight Test Pilot School at Edwards in August 1960. It involved flying on a totally new level. ‘‘Fighter pilots can be impetuous; test pilots can’t,’’ Collins recounted years later. ‘‘They have to be more mature, a little bit smarter. . . more deliberate, better trained – and they’re not as much fun as fighter pilots.’’ By this time, he had accumulated over 1,500 hours in his logbook, the minimum requirement for a prospective student at the exalted school. (In fact, his class included future astronauts Frank Borman and Jim Irwin.)

|

|

An exhausted Cernan puts on a brave face for Tom Stafford’s camera after finally removing his helmet. The world’s longest EVA to date had uncovered a chilling reality: that spacewalking was hazardous and by no means routine.

Two years later, when John Glenn completed America’s first orbital spaceflight, Collins took notice and submitted his application for the 1962 astronaut intake. He underwent the full physical and psychological screening process, narrowly missing out on selection and, despite his disappointment, moved on to study the basics of spaceflight, flying the F-104 Starfighter to altitudes of 27 km and receiving his first taste of weightlessness. He had barely returned to fighter operations when, in June 1963, NASA announced its intent to choose more astronauts. Years later, Deke Slayton would write that the 1962 selection panel considered Collins a good candidate who had been “held back to get another year of experience”.

Initial instruction as part of the third class of 14 spacefarers, whom the press widely dubbed ‘The Apollo Astronauts’, included lunar geology, a subject for which Collins had no great enthusiasm or interest; ironic, perhaps, in view of where his career would eventually take him. Although he felt, like Slayton, that the New Nine was probably the best all-round astronaut group yet chosen, Collins admitted that the Fourteen were the best-educated: with average IQs of 132, an average 5.6 years in college and even an ScD among them.

Completion of initial training led to assignment to oversee the G4C extravehicular suit and he would express annoyance at being left out of the loop in May 1965 when a closed-door decision was made to give Ed White a spacewalk on Gemini IV. In his autobiography, Collins described the suit and the astronaut’s relationship with it, as “kind of love-hate… love because it is an intimate garment protecting him 24 hours a day, hate because it can be extremely uncomfortable and cumbersome”. The suit, and the timeline for which astronauts were to get fitted for it, provided a never – ending source of rumour as to who would be assigned next to a mission slot.

Recognition for this work came in June 1965 with a backup assignment, teamed with Ed White, to Gemini VII. Despite falling ill with viral pneumonia shortly thereafter, Collins recovered promptly and performed admirably, even taping a ‘Home Sweet Home’ card inside Jim Lovell’s window on launch morning. His eventual assignment, with John Young, to Gemini X came in January 1966, by which time White had been named to the first Apollo mission. ‘‘I was overjoyed,’’ wrote Collins. ‘‘I would miss Ed, but I liked John, and besides I would have flown by myself or with a kangaroo – I just wanted to fly.’’