LAST MERCURY OUT

Cooper’s hotshot characteristics were balanced by a misleadingly quiet voice and laid-back personality, to such an extent that he frequently fell asleep during the lengthy physical checks… and, famously, dozed off aboard his Faith 7 spacecraft, atop the fully-fuelled Atlas, on launch morning. Al Shepard, for his part, had lost his last chance to fly the final Mercury mission. Despite having himself engaged in flat – hatting as a naval aviator, he told Walt Williams that he felt Cooper had shown ‘‘unusually bad judgement’’. However, wrote Neal Thompson, ‘‘it wasn’t the height Shepard thought was dumb; it was buzzing the administration building’’.

Four hours after a still-enraged Williams had given his consent to let Cooper fly, early on 14 May, the prime and backup astronauts ate breakfast… and Shepard got more revenge for his ‘lost’ mission through another tension-relieving, though somewhat mean-spirited, gotcha. Press spokesman Shorty Powers arrived early that morning with a pair of cameramen to shoot some behind-the-scenes footage of Cooper as he prepared for launch. However, they found, to their shock, that none of

|

Cooper’s Atlas 130D booster is prepared for launch. |

the overhead lights were working, nor, indeed, were any of the electrical sockets. Someone, it seemed, had cut the wires, removed every light bulb, inserted thick tape into the sockets and replaced the bulbs. No one pointed any fingers, but Powers recognised the grin on Shepard’s face “that is typical of him when he has a mouse under his hat’’.

Another gift from Shepard awaited Cooper when he boarded Faith 7 at 6:36 am: a small suction-cup pump on the seat, labelled with the legend ‘Remove before launch’, in honour of the new urine-collection device aboard the spacecraft. Cooper would become the first Mercury astronaut who would be able to urinate in a manner other than ‘in his suit’. At this stage, the only expression of doubt over whether Faith 7 would fly came from meteorologist Ernest Amman. His fears were soon realised, not because of the weather, but due to a malfunctioning C-band radar at the mission’s secondary control centre in Bermuda. Shortly after this had been rectified, at 8:00 am, with an hour remaining before the scheduled launch, a simple 275- horsepower diesel engine, responsible for moving the gantry away from the Atlas, stubbornly refused to work. More than two hours were wasted in efforts to repair a fouled fuel injection pump on the engine and the count resumed around noon. The gantry was successfully retracted, but the failure of a computer in Bermuda – crucial for a ‘go/no-go’ launch decision to be made – caused the attempt to be scrubbed.

Cooper, after six hours on his back inside Faith 7, remained upbeat and summoned a forced grin. ‘‘I was just getting to the real fun part,’’ he said. ‘‘It was a very real simulation.” He spent part of the afternoon fishing, while checkout crews prepared the Atlas for launch the following morning. Arriving at Pad 14 for the second time, he greeted Guenter Wendt, with mock formality, reporting as ‘‘Private Fifth Class Cooper’’, to which the pad fuehrer responded in kind. The roots of their joke came two years earlier, when Cooper had stood in for Al Shepard in a launch – day practice run prior to Freedom 7. Upon arriving at the pad, Cooper had expressed mock terror, begging Wendt not to make him go, in true Jose Jimenez fashion. Some of the assembled media were amused, but NASA’s public affairs people were not and one even suggested that Cooper be ‘‘busted to Private Fifth Class’’. Ironically, the astronaut and Wendt liked the idea and ran with it.

This time, his wait inside the spacecraft lasted barely two and a half hours. The countdown ran smoothly until T-11 minutes and 30 seconds, when a problem developed in the rocket’s guidance equipment and a brief hold was called until it was resolved. In fact, so smooth was the countdown that flight surgeons were astonished to note that Cooper’s heart rate had fallen to just 12 beats per minute: he had dozed off. It took Wally Schirra, the capcom at Cape Canaveral, to bellow his name over the communications link to awaken him. Agonisingly, another halt came just 19 seconds before liftoff to allow launch controllers to ascertain that the Atlas’ systems had assumed their automatic sequence as planned.

Thirteen seconds after 8:00 am on the morning of 15 May, the Atlas rumbled off its launch pad in what Cooper would later describe as a smooth but definite push. A minute into the climb, the silvery rocket initiated its pitch program and the astronaut felt the vibrations of Max Q, after which the flight smoothed out and he heard a loud clang and the sharp, crisp ‘thud’ of staging as the first-stage boosters cut off and separated. Unneeded, the LES tower was jettisoned and, at 8:03 am, Faith 7’s cabin pressure sealed and held, as intended. Two minutes later, the sustainer completed its own push, shutting down and inserting the spacecraft perfectly into orbit. It was so good, in fact, that the heading was 0.0002 degrees from perfect, Cooper’s velocity was right on the money at 28,240 km/h and his trajectory set him up for at least 20 circuits of the globe. Said Wally Schirra as America’s sixth spaceman entered orbit: “Smack-dab in the middle of the plot!’’

Cooper watched for about eight minutes as the sustainer tumbled away and then moved to his checklists, running through temperature readings, contingency recovery areas and began the process of adjustment to weightlessness. So rapid was Faith 7’s passage across the Atlantic – accomplished in a matter of minutes – that he expressed surprise when called by the capcoms in the Canaries and Kano in Nigeria. Sigma 7 had been near-perfect and it seemed that Cooper’s mission would match or excel it; he dozed off for a few minutes during his second orbit, as the spacecraft passed over a lonely stretch of the Pacific, between Hawaii and California. Flight surgeons would note that his heart rate surged momentarily from 60 to 100 beats per minute, suspecting that he was having an exciting, though somewhat brief dream. At one stage, things were running so well that Capcom Al Shepard had nothing to say, except to offer Cooper some quiet time. Not until the following day, 16 May, would serious problems arise and allow him to demonstrate his skills as a pilot.

He was by no means inactive. His tasks including eating – brownies, fruit cake and some bacon – as well as Earth observations, photography, collection of urine samples and monitoring Faith 7’s health. His efficient use of the cabin oxygen even prompted Shepard to tell him to “stop holding your breath and use some oxygen if you like’’. Cooper’s response was that, as the only non-smoker among the Mercury Seven, his lungs were in better shape than his colleagues. Not only was his oxygen expenditure economical, but so too was his fuel usage, prompting mission managers to nickname him, good-naturedly, a “miser”. As Faith 7 embarked on its second orbital pass, Shepard reiterated that the flight was proceeding beautifully and “all of our monitors down here are overjoyed’’. In fact, Cooper’s only complaint during this period was of a thin, oily film on the outside pane of his trapezoidal window.

Beginning with the third orbit, the astronaut set to work on the first of 11 scientific experiments assigned to his mission. One of these was a 15 cm sphere, instrumented with two xenon strobe lights, part of efforts to track a flashing beacon in space. Three hours and 25 minutes after launch, he clicked a squib switch and heard and felt the experiment separate successfully. However, despite repeated efforts, he could not see the flashing beacon in orbital darkness. He would later catch a glimpse of it pulsing at sunset, during his fourth circuit of the globe, telling Capcom Scott Carpenter with jubilation: “I was with the little rascal all night!’’ Cooper reported seeing the beacon flickering during his fifth and sixth orbits, too. Another major experiment, the deployment of a 76 cm Mylar balloon, painted fluorescent orange for visibility, was less than successful. Nine hours into the mission, he set cameras, attitude and spacecraft switches to release the balloon from Faith 7’s nose, but it refused to move. Another attempt also proved fruitless. The intention of the balloon – similar to that flown on Carpenter’s mission – was for it to inflate with nitrogen and extend out on a 30 m nylon tether, after which a strain gauge would measure the differences in ‘pull’ at Faith 7’s apogee of 270 km and perigee of 160 km. Sadly, the cause of the failure was never determined.

Cooper was, however, able to observe not only a flashing beacon in space, but also a xenon ground light of three million candlepower, situated at Bloemfontein in South Africa. He would also make detailed mental notes throughout the flight as he flew over cities, large oil refineries near Perth in Australia, roads, rivers, small villages and even saw smoke from Himalayan houses. Although he pointed out that the finer details could only be seen if lighting and background conditions were right, his sightings were disputed after the mission, but Gemini astronauts would later confirm them. Further theoretical confirmation came from visibility researchers S. Q. Dunt and John H. Taylor of the University of California at San Diego. In a paper published in October 1963, they highlighted Cooper’s observation of a dust cloud, presumably kicked up by a vehicle travelling along a dirt road near El Centro, on the border between Mexico and the United States.

‘‘Calculation shows that the vehicle, plus the dust cloud behind it, is more visible than the road itself,’’ agreed Dunt and Taylor in their report. ‘‘It is possible, moreover, that the appearance of the dust cloud would create the impression of having a lighter tip at its eastern end. There is reason to believe, therefore, that the presence of a moving Border Patrol vehicle on the dirt road near El Centro could have been seen from orbital altitude under the atmospheric and lighting conditions which we believe to have prevailed at the time of Major Cooper’s observation.’’

Several other scientific experiments, in fact, encompassed photography. Before the mission, Cooper spent time with University of Minnesota researchers on an investigation into the mysterious phenomena of the zodiacal light and the nighttime airglow layer, as part of efforts to better understand the origin, continuity, intensity and reflectivity of visible electromagnetic spectra along the basic reference plane of the celestial sphere. His work would also help to answer questions about solar energy conversion in Earth’s upper atmosphere. Many of the zodiacal light photographs turned out to be underexposed and the airglow shots overexposed, but they were nonetheless of usable quality and complemented Carpenter’s images from Aurora 7. Flying over Mexico, Cooper photographed horizon-definition imprints in each quadrant around his local vertical position, part of a Massachusetts Institute of Technology project to design a guidance and navigation system for Apollo. Lightheartedly complaining that all he seemed to be doing was taking pictures, Cooper acquired some excellent imagery, including infrared weather photographs.

Surpassing Wally Schirra’s nine-hour endurance record for the United States, Cooper settled down to a battery of radiation experiments to ascertain that the effects of the Operation Dominic artificial aurora were indeed diminishing. He also undertook the hydraulic tasks of transferring urine samples and condensate water between storage tanks. Physicians had expressed particular interest in urine checks and the Soviets had already highlighted significant accumulations of calcium in their cosmonauts’ urine, suggesting that extended spaceflights could adversely affect human bones. Cooper found the hypodermic-type syringes used to pump liquid manually from bag to bag to be unwieldy and exasperatingly leaky, even telling his on-board tape recorder that “this pumping under zero-G is not good. [Liquid] tends to stand in the pipes and you have to actually forcibly force it through”.

Ten hours into the mission, the Zanzibar capcom officially informed Cooper that his flight parameters – circling the globe every 88 minutes and 45 seconds – were good enough for 17 orbits. Shortly before retiring for a scheduled sleep period on his ninth revolution, Cooper ate a supper of powdered roast beef mush, drank some water and checked Faith 7’s systems to ensure that they could be powered down for the next few hours. His orbital speed was truly phenomenal: after speaking to Capcom John Glenn, based on the Coastal Sentry Quebec tracking ship, near Kyushu, Japan, he swept south-eastwards over the Pacific and gave a full report to the telemetry command vessel Rose Knot Victor, positioned near Pitcairn Island… just ten minutes later!

The Pitcairn communicator told Cooper to get some rest, but that proved almost impossible. Passage over South America, then Africa, northern India and Tibet, during daylight, offered wonderful viewing and photographic opportunities. The Tibetan highlands, with their thin air and visibility seldom obscured by haze, allowed him to make rudimentary estimates of his speed and ground winds from the direction of chimney smoke. In their paper, Dunt and Taylor suggested that ground – reflectance modelling made it not impossible for Cooper to have seen such fine details. Thirteen and a half hours into the flight, Glenn told him that the communicators would leave him alone and Cooper pulled a shade across Faith 7’s window to get some sleep. The astronaut dozed intermittently for around eight hours, anchoring his thumbs at one stage inside his helmet restraint strap to keep his arms from floating freely. He woke briefly when his pressure suit’s temperature climbed too high and over the next several hours he napped, took photographs, taped status reports and cursed to himself as his body-heat exchanger crept either too high or too low.

Faith 7 swept silently over the Muchea tracking site on its 14th orbit and Cooper, by now fully alert, again checked its systems, finding his oxygen supply to be plentiful and around 65 per cent and 95 per cent of hydrogen peroxide fuel, respectively, in his automatic and manual tanks. At around this time, he said a brief prayer to offer thanks for an uneventful mission: “Father, we thank you, especially for letting me fly this flight. Thank you for the privilege of being able to be in this position, to be in this wondrous place, seeing all these many startling, wonderful things that you have created.’’ Slow-scan television images of Cooper, the first ever transmitted by an American astronaut, were broadcast during his 17th orbit and he even sang one revolution later. The prayers and light moments, it seemed, actually marked the beginning of Faith 7’s troubles.

Early on his 19th circuit of Earth, some 30 hours after liftoff, the first of several serious problems reared its head. Cooper was flying over the western Pacific, out of radio communications with the ground, when he dimmed his instrument panel lights… and noticed the small ‘0.05 G’ indicator glow green. This should normally have illuminated only after retrofire, as Faith 7 commenced its manoeuvre out of orbit, and should also have been quickly followed by the autopilot placing the spacecraft into a slow roll. Initial worries that Cooper had inadvertently slipped out of orbit were refuted a few minutes later by the Hawaii capcom, who told him his orbital parameters held steady, suggesting either that the indicator was faulty or that the autopilot’s re-entry circuitry had been triggered out of its normal sequence.

An orbit later, the astronaut was advised to switch to autopilot and Faith 7 began to roll. This had its own implications. For proper flight, Time magazine told its readers a week later, there were other functions for the autopilot to perform prior to retrofire. Since each function was sequentially linked to the next, Mercury Control knew that several earlier steps had not been performed. Cooper would have to control them by hand, a situation not entirely unpalatable, since Scott Carpenter had flown part of his re-entry in a similar manner. Still, at Cape Canaveral, a training mockup of the spacecraft in Hangar S was set up to practice various scenarios and provided an assurance that all would be well. Then, on its 20th orbit, Faith 7 lost all attitude readings and, a revolution later, one of its three inverters, needed to convert battery power to alternating current and operate the autopilot, went dead. Cooper tried to activate a second inverter, but could not. (The third inverter was needed to run cooling equipment inside the cabin throughout re-entry.) His autopilot, in effect, was devoid of all electrical power.

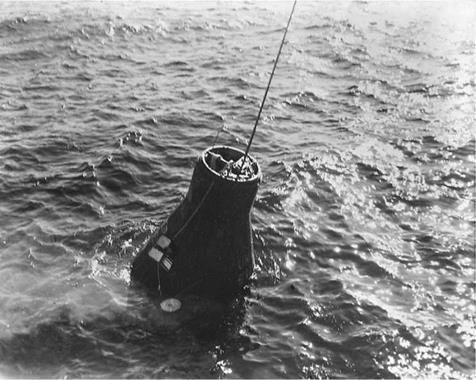

|

A Mercury capsule after splashdown. |

As flight controllers scrambled to relay questions, corrections and instructions and practice procedures on the ground – including the possibility of bringing Cooper back to Earth on battery power alone – the astronaut himself remained calm, though he watched in dismay as carbon dioxide levels rose both inside the cabin and within his pressure suit. The lack of electrical power meant that he could not rely on his gyroscopic system to properly orient Faith 7 for re-entry; it would have to be lined up manually. He could not even rely on the spacecraft’s clock. “Things are beginning to stack up a little,’’ he told Capcom Scott Carpenter in a cool and typically understated manner, but acquiesced that he still had fly-by-wire and manual controls as a backup. “We would have found some way to fire the retros,’’ Mercury engineer John Yardley said later, “if it meant telling him what wires to twist together.’’

Guided by John Glenn, aboard the Coastal Sentry, Cooper ran smoothly through his pre-retrofire checklist, steadying Faith 7 with the hand controller and lining up a horizontal mark on his window with Earth’s horizon; this brought the spacecraft’s nose down to the desired 34-degree angle. Next, he lined up a vertical mark with predetermined stars to gain the correct yaw angle. Glenn counted him down to retrofire and Cooper hit the button on time, receiving no light signals, because of his electrical system problems, but he confirmed that he could feel the three small engines igniting. Re-entry was uneventful, with Cooper damping out unwanted motions and manually deploying his drogue and main parachutes. The spacecraft broke through mildly overcast skies and splashed into the Pacific, some 130 km south-east of Midway Island, only 6.4 km from the recovery ship Kearsarge. Floundering briefly, Faith 7 quickly righted itself and Cooper requested permission, as an Air Force officer, to be allowed aboard a naval carrier.

Forty minutes later, permission having been granted, the hatch was blown and America’s sixth astronaut set foot on the deck of the Kearsarge. His mission had lasted 34 hours, 19 minutes and 49 seconds – nowhere close to the four days chalked – up by Andrian Nikolayev a year earlier, but a significant leap as NASA prepared for its ambitious series of long-duration Gemini flights. Even more significantly, Cooper had returned to Earth as all the astronauts had wanted: as a pilot in full control. It also offered a jab at the test pilot community, some of whom had ridiculed Project Mercury as little more than ‘a man in a can’ or, even more deridingly, as ‘spam in a can’. Walt Williams, who only days earlier had tried to have Cooper removed from the flight, now warmly shook the astronaut’s hand. ‘‘Gordo,’’ he told him, ‘‘you were the right guy for the mission!’’

The future seemed bright. Ahead, in a year’s time, lay Gemini. . . and then the Moon.