NEIL ARMSTRONG

Stephen Koenig Armstrong and Viola Louise Engel were married on 8 October 1929, and their son Neil Alden Armstrong was born on 5 August 1930 on his maternal

|

|

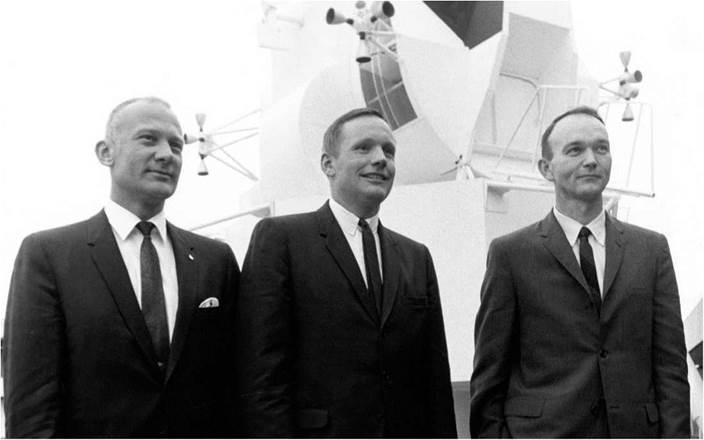

![]() On 10 January 1969 Buzz Aldrin, Neil Armstrong and Mike Collins pose in front of a mockup of the LM at the Manned Spacecraft Center following their first press conference as the crew of Apollo 11.

On 10 January 1969 Buzz Aldrin, Neil Armstrong and Mike Collins pose in front of a mockup of the LM at the Manned Spacecraft Center following their first press conference as the crew of Apollo 11.

grandmother’s farm, some 6 miles from the small town of Wapakoneta, Ohio. The Armstrong family hailed from the border country of Scotland, and the Engels from Germany. As an auditor, Stephen Armstrong was constantly travelling the state (it took about a year to audit the books for a county) setting up temporary home in a succession of small towns. June was born in 1932, and Dean 19 months later. Neil was a non-conformist, spending his time playing the piano and voraciously reading books. He developed an early passion for flying, and by 9 years of age he was building his own model aircraft. “They had become, I suppose, almost an obsession with me,’’ he later reflected. He read everything he could lay his hands on about aviation, filling notebooks with miscellany.

When Neil was 14, the family settled in Wapakoneta (although born nearby, he had not actually lived there). The money from out-of-school jobs, initially stocking shelves at 40 cents per hour in a hardware store, and later working at a pharmacy, helped to pay for flying lessons at $9 each. He gained his student pilot’s licence on his sixteenth birthday, but had not yet felt the need for a driver’s licence. It was apparent that he would need a technical education if he was to become a professional pilot, but the family did not have the resources to send him through college. Although he was not specifically interested in military aviation, the Navy offered scholarships for university in return for time in service afterwards. Neil applied, and in 1947 was accepted. On the advice of a high school teacher, he went to Purdue University in Indiana because it had a strong aeronautical engineering school. After he had been there 18 months, the Navy – as it was entitled to do – interrupted his studies and sent him to Pensacola in Florida for flight training. He opted for single-seat rather than multi-engine aircraft because he “didn’t want to be responsible for anyone else’’ by having a crew. The Korean War broke out on 25 June 1950 and he gained his ‘wings’ soon thereafter. In view of the situation, his return to college was deferred and he was sent to the West Coast for additional training. In mid-1951 he was sent to the USS Essex to fly F9F Panthers with Fighter Squadron 51, one of the early ‘all jet’ carrier squadrons. Although he had been trained for air combat, most of his missions were low-level strikes against bridges, trains and armour. On 3 September 1951 he flew so low that he struck a cable and damaged one wing, but was able to nurse his stricken aircraft back over friendly lines before ejecting. In all, he flew 78 combat missions.

In early 1952 he returned to the USA. Rather than attend a military academy in order to receive a commission, he resigned from the Navy and resumed his studies at Purdue, where he met fellow student Janet Elizabeth Shearon. He was then 22 and she was 18; her father was a physician in Welmette, Illinois, and Janet was the youngest of three sisters. On graduating in 1955 with a degree in aeronautical engineering, he was recruited as a research pilot at the High-Speed Flight Station operated by the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics at Edwards Air Force Base in the high desert of the San Gabriel mountains of California. On his drive west, Neil detoured to Wisconsin, where Janet was working, to ask her to marry him; she agreed to think it over. They were married on 28 January 1956, and their first home was a small cabin with neither electricity nor running water, off base among the Joshua trees and rattlesnakes of the Juniper Hills. This was ‘‘the most fascinating time of my life,” Armstrong later reflected. “I had the opportunity to fly almost every kind of high-performance airplane, and at the same time to do research in aerodynamics.” The X-15 was a sleek black rocket-powered aircraft which, in a zooming climb following release from a B-52, was able to rise above the bulk of the atmosphere. Armstrong first flew the X-15 in I960, and in all he tested the aircraft seven times. His highest altitude was 207,000 feet, but this did not set a record. However, “above 200,000 feet, you have essentially the same view you’d have from a spacecraft when you are above the atmosphere. You can’t help thinking, by George, this is the real thing. Fantastic!’’ Armstrong helped in the development of the advanced flight control system for the vehicle. Like many at Edwards Air Force Base, he felt that the route into space would be by ever faster aircraft. When a NASA recruiter arrived at Edwards seeking Project Mercury ‘astronauts’ to ride in a ‘capsule’ that would parachute into the ocean, Armstrong was not interested. ‘‘We reckoned we were more involved in space flight research than the Mercury people, but after John Glenn orbited Earth three times in a little less than 5 hours on 22 February 1962, we began to look at things a bit differently.” In April 1962 NASA sought its second intake of astronauts. The first group had all been military test pilots. Although test pilot experience was still a requirement, civilians were now allowed to apply. Candidates had to have a college degree in an engineering subject, be no taller than 6 feet, and not exceed 35 years of age at the time of selection. Armstrong was blond, blue eyed, 165 pounds, 5 feet 11 inches tall, and had a few years to spare. He submitted his application. Of all the civilian applicants, he had by far the greatest experience. On 17 September he was announced as one of nine new astronauts. By the end of the year, the Armstrongs had relocated to El Lago, a housing development near the Manned Spacecraft Center at Clear Lake, which, being neither a lake nor clear, was an alluvial mud flat on Galveston bay about 30 miles from Houston.

Although about the same age as his group, Armstrong looked much younger. He did not match the popular image of an astronaut as a hard-drinking, adrenaline – primed partier. In fact, he was notable for not jogging or doing pushups (which the others did eagerly in pursuit of physical fitness) and his social life was spent with his family.

Each astronaut ‘tracked’ some aspect of the space program to ensure that the astronauts’ points of view were represented, and to report back in order to enable the astronaut office to be aware of everything that was going on. While a civilian research test pilot at Edwards, Armstrong had been involved in the development of new flight simulators, whereas military test pilots merely used them. It was logical, therefore, that he should be assigned to monitor the development of trainers and simulators.

Deke Slayton opted to fly the military pilots of the second group ahead of the civilians. After jointly backing up Gemini 5 Armstrong and Elliot See were given separate assignments, with Armstrong commanding Gemini 8 and See commanding Gemini 9. On 16 March 1966 Armstrong and Dave Scott were launched into orbit and, after a perfect rendezvous with an Agena target vehicle, they achieved the first docking between vehicles in space. Unfortunately, several minutes later, and now in

|

The Apollo 11 crew |

On 9 April 1959 NASA announced the recruitment of its first group of astronauts: (left to right, seated) Leroy Gordon Cooper Jr, Virgil Ivan ‘Gus’ Grissom, Malcolm Scott Carpenter, Walter Marty Schirra Jr, John Herschel Glenn Jr, Alan Bartlett Shepard Jr and Donald Kent ‘Deke’ Slayton.

On 17 September 1962 the second group was announced: (left to right, standing) Edward Higgins White II, James Alton McDivitt, John Watts Young, Elliot McKay See Jr, Charles ‘Pete’ Conrad Jr, Frank Frederick Borman II, Neil Alden Armstrong, Thomas Patten Stafford and James Arthur Lovell Jr.

On 17 October 1963 NASA announced its third group of astronauts: (left to right, standing) Michael Collins, Ronnie Walter Cunningham, Donn Fulton Eisele, Theodore Cordy Freeman, Richard Francis Gordon Jr, Russell Louis ‘Rusty’ Schweickart, David Randolph Scott and Clifton Curtis Williams; (seated) Edwin Eugene ‘Buzz’ Aldrin Jr, William Alison Anders, Charles Arthur Bassett II, Alan LeVern Bean, Eugene Andrew Cernan and Roger Bruce Chaffee.

Buzz Aldrin 9

darkness, the docked combination became unstable. Thinking that the fault must be associated with the Agena they undocked, only to find themselves in an accelerating spin owing to the fact that one of their thrusters was continuously firing. By the time the rate of spin had reached one rotation per second, ‘tunnel vision’ had set in and a black-out was imminent, but Armstrong was able to regain control by shutting off the primary attitude control system and switching to the thrusters designed for use during atmospheric re-entry, which in turn necessitated an emergency return, which was carried out successfully.

At the time of Apollo 11, the Armstrong family comprised Neil and Jan, and sons Ricky, aged 12, and Mark, 6.