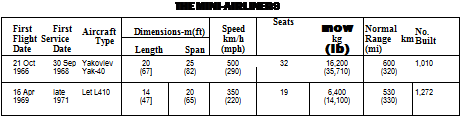

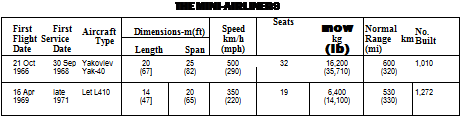

. Yakovlev Yak-40 and Let L410UVP-E

Ivchenko AI-25 (3 xl,500kg st,3,3001b st) ■ MTOW 13,700kg (30,2001b) ■ Normal Range 600 km (320mi)

|

|

|

|

Ivchenko AI-25 (3 xl,500kg st,3,3001b st) ■ MTOW 13,700kg (30,2001b) ■ Normal Range 600 km (320mi)

|

|

|

|

50 TONS ■ 750km/h (470mph)

Soloviev D-30KP (4 x 12,000kg st, 26,4551b st) ■ MTOW 170,000kg (375,0001b) ■ Normal Range 3,650km (2,190mi)

The Second Big Freighter

The Antonov An-22 (see page 67) had captured the aviation world’s attention during the mid – 1960s, with its impressive size and the ability to carry 80 tons of cargo. When the Ilyushin 11-76 made its maiden flight at Moscow’s almost-downtown Khodinka airfield on 25 March 1971, it did not attract quite as much publicity, possibly because it did not beat any records in sheer size. Its all-up weight was about 44 tons less than the big Antonov’s, but it was nevertheless just as impressive, and appears to have been more popular with the operators, as far more Il-76s are to be seen the length and breadth of Russia and the former Soviet republics than its larger rival.

The big freighter went into series production for civil use as the 11-76T in 1975, and deliveries began to Aeroflot in 1976. Like the Antonov series of heavy lifters, the 11-76 had a pronounced anhedral wing, and — also like the An-22 (and the Lockheed C-141) — it had superb short-field and rough-field performance, thanks to the manner in which the total weight of the aircraft was distributed among the multiple-wheeled landing gear. Sixteen main wheels are mounted in fuselage pods, and are arranged in banks of tandem axles, four abreast on each side. The 11-76 can carry 40 tons, but habitually carries loads of around 20 tons over ranges of about 7,000km (4,000mi), i. e. nonstop from Moscow to Khabarovsk or Yakutsk. It can moreover make this performance to and from airfields with runways about 1,700 meters (one mile) in length.

Universal Popularity

Such versatility makes it almost indispensable for long-range cargo operations, especially as its 24-meter (almost 80ft) – long cargo hold is more than 3m (10ft) high and wide. Every main traffic center of Aeroflot, and especially the big air traffic centers in Siberia, enjoys regular air cargo connections with all corners of the system, from Murmansk to Vladivostok; and it is especially welcomed at Yakutsk, which is not served by rail, and where road and river traffic is burdensome and restricted to a short season. A longer range variant, the I1-76TD, went into production in the early 1980s.

The Ilyushin Il-76’s finest hour, however, was almost certainly when it made a flight to Antarctica in 1986, and repeated the performance in 1987 and 1989. For this operation, it was able to alight on packed snow and on slick ice, both challenges to airmanship and aircraft integrity. These remarkable long-distance heavy-lift sorties are described on page 71.

The Ilyushin Il-76’s finest hour, however, was almost certainly when it made a flight to Antarctica in 1986, and repeated the performance in 1987 and 1989. For this operation, it was able to alight on packed snow and on slick ice, both challenges to airmanship and aircraft integrity. These remarkable long-distance heavy-lift sorties are described on page 71.

Lotarev P-36 (3 x 6,500kg st, 14,330ib st) ■ MTOW 56,500kg (124,5601b) ■ Normal Range 2,200km (l,320mi)

Early Promise

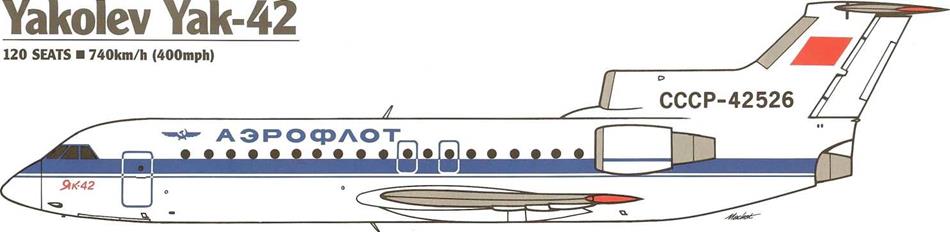

Soviet aircraft that traditionally attracted attention in the West, notably at such shop windows as the Paris Air Show, did so because they were bigger or faster than had ever been seen before. The Yakovlev Yak-42 was different. When it first flew on 7 March 1975 (as a 100-seater), and when Aeroflot ordered 200 of the new trijet in June 1977, the world sat up and took notice; because at last, it was suspected, the Soviet Union had produced an airliner that could compare with equivalent western types, not only in performance, but also in operating, efficiency.

Although Aeroflot discussed the possibility of the 120-seat Yak-42 being a replacement for a wide range of obsolescent types, from the Antonov An-24 to the Ilyushin 11-18, it was directed mainly to supersede the Tupolev Tu-134 80-seat twin. Certainly, the figures look promising. The 120-seat six-abreast Yak-42 was only five tons heavier than the four-abreast Tu-134, and was not much bigger. It needed only two crew members, instead of the three or four of the Tupolev. It had good short-field performance, could use rough airstrips, and had the additional features of built-in airstairs and baggage racks on each side of the door entrances. It seemed to fit halfway between the Tupolev Tu-134 twin and the Tupolev Tu-154 trijet, and a great future seemed assured.

The Pace Slackens

The Yakovlev Yak-42 entered service with Aeroflot in November 1980, on routes such as Moscow-Kostroma and Leningrad-Helsinki. Later on, it was introduced as a back-up to the heavy air corridor traffic to the Caucasus; and it operated to Prague, both from Kiev and Lvov.

The introduction of the Yak-42 was marred by many technical problems and, following an in-flight structural failure of the tailplane, the type was withdrawn from service in the early 1980s. After more than 2,300 design changes, it re-entered Aeroflot service in the late 1980s and quickly gained an impressive reputation for reliability, efficiency, and economy.

|

In 1990, the longer range 120-seat Yak-42D was introduced, and is probably one of the most comfortable Russian-built aircraft in the Aeroflot fleet. By June 1992, 115 Yak-42s and 50 Yak – 42Ds had been delivered to Aeroflot.

4 SEATS ■ 165km/h (105mph)

A Great Airliner

To the relief of the whole of Europe, the Armistice of 11 November 1918 brought an end to the Great War, Professor Junkers drew on the experience of building military aircraft almost entirely of metal, and designed one of the most successful transport aircraft of the 1920s, and one of the great airliners of all time.

Designated the Junkers-F 13 — defying superstition — it first went into service in Germany in 1919, and the last F 13 in scheduled service retired in Brazil in 1948. Constructed of corrugated light-weight aluminum, it easily outlived the wood-and-fabric steel-framed aircraft of the time, few of which survived for more than two or three years — and would not have lasted long in northern Russia or Siberia.

Restrictive Practices

The F 13s were, like all German aircraft, handicapped by severe restrictions imposed by the victorious Allies. In May 1920, all German aircraft were confiscated by the occupying powers, and under the terms of the ‘London Ultimatum’ of 5 May 1921, these were enforced with even more severity. Not until 14 April 1922 was the ban on aircraft construction finally lifted, albeit with limitations on engine power and load carrying.

German companies evaded the letter — and the intent — of the law by setting up production in other countries. It also sponsored the formation of airlines in those countries which had no aircraft industries of their own (and even one or two that had) by setting up joint ventures. The host country supplied the infrastructure of installations, airfields, and administrative staff; Junkers supplied the aircraft and technical support.

The little four-passenger F 13 carried its customers in a comfortable cabin, in comfortable seats; however, the two crew sat in a semi-open cockpit. Altogether, over 300 F 13s were built, an astonishing production performance for the period, and the F 13 formed the basis for later types such as the W 33, and ultimately the Ju 52/3m. The F 13s were to be seen all over Europe, in South America, and in other countries such as Persia and South Africa.

Technical Slowdown

Although the ANT-9 of the late 1920s had been on a par with the commercial aircraft of other countries; and the ANT-6 had been an adequate heavy lifter, Soviet designers lost momentum during the 1930s. Kalinin was executed. Tupolev himself spent much of his time under house arrest, and escaped being shot only by the intervention of, of all people, Beria, head of the secret police.

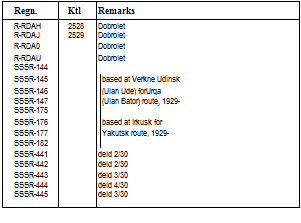

Buying the Best

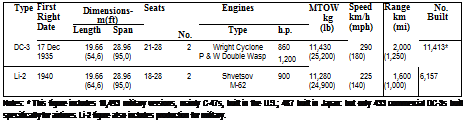

In August 1935, AMTORG (American Trading Organization) in New York, took delivery of the first DC-2 (NC14949, msn 1413) and Boris Lisunov was sent to California to prepare for the licensed production of the Douglas twin. The Soviet-built Douglases were first designated PS – 845 (Pashazhyrski Samolyet, or passenger aircraft), and from 17 September 1942, Lisunov Li – 25. These were standard DC-3s, with a right-side – entry door. By the end of World War II, 2,258 had been built. The type remained in production until 1954, by which time a total of 6,157 had been built at Tashkent, Uzbekistan.

Lend-Leases

After the Nazi invasion of the summer of 1941, much of western Russia and the Ukraine had been devastated or pillaged. In a mighty display of determination and improvised organization, all the aircraft production lines in Europe were moved eastwards to cities beyond the Ural Mountains. This massive logistics task took many months, and meanwhile the Air Force had to be reinforced.

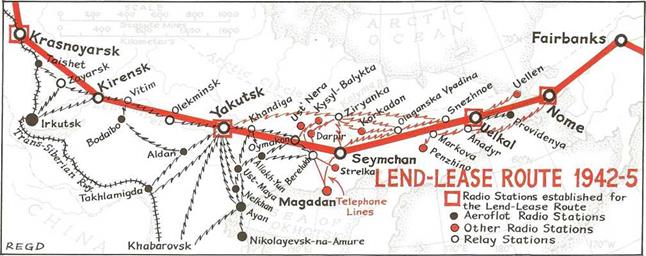

At an Allied conference in Moscow on 31 July 1941, Harry Hopkins, President Roosevelt’s special envoy, laid the foundations of what was to become the Lend-Lease Program. Slow to get under way at first — few aircraft arrived in time for the Battle of Moscow, and these were from Britain, via Murmansk — the unprecedented machinery of the historic airlift began on 29 September 1942, when the first Bell P-39 Airacobra left Fairbanks, Alaska, and arrived in time to go into action early in October.

Of the 18,700 aircraft supplied under the Allied Lend – Lease program, 14,750 were flown along this route, by U. S. pilots to Fairbanks, where Soviet flyers took over. Of these, over 4,900 were P-39 Airacobras, 2,400 P-63 Kingcobras,

2,900 Douglas DB-7/A-20 Havocs, and 860 North American B-25 Mitchells. About 640 were lost in transit. The Lend – Lease aircraft accounted for 12% of the 136,800 of all types used by the Soviet Air Force in the Great Patriotic War.

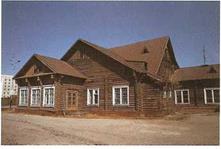

Of the several other types, other than those mentioned above, 700 were Douglas C-47s, the most widely used of the military variants of the DC-3 workhorse transport airplane. They were used everywhere. The Soviet pilots liked them as much as did the U. S.A. A.F. ‘Gooney Bird’ and the R. A.F. Dakota flyers. And they were to make a solid contribution to Aeroflot’s recovery after the conflict came to an end. On 1 March 1946, for instance, the 14th Cargo Aircraft Group of Aeroflot was formed at Yakutsk. Fifteen C-47s were transferred from the Soviet air fleet, together with, remarkably, three Junkers-Ju 52/3m’s that had been captured on the eastern front.

COMPARISON OF DOUGLAS DC-3 AND LISUNOV LI-2

|

|

The old Yakutsk terminal building, in traditional Russian wood construction, first erected for the Lend-Lease program, is still there, as this photo, taken in 1992, shows. Just down the street is the original building which housed the offices of the Lend-Lease program during the vital years, 1942-1945. (R. E.G. Davies)

|

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

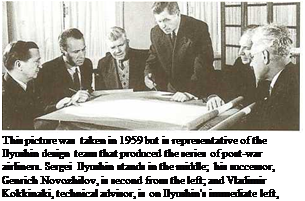

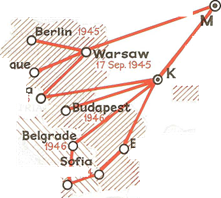

Resumption of European Services

The Soviet Union emerged from World War II (The Great Patriotic War) weakened by its sustained and intensive efforts to beat the Nazi war machine into the ground. Aeroflot had to re-group as the national flag carrier, as Moscow began to isolate itself from its allies in the west, at the same time trying to dominate the countries on its borders, simultaneously spreading the creed of communism and fashioning a cordon sanitaire to guard against a repetition of the events of 1920.

In 1944, the U. S.S. R. had declined an invitation to attend the historic Chicago Conference, at which most of the world’s nations hammered out the basis for what was to become the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO). The Five Freedoms of the Air were not wholly accepted in Moscow, where, nevertheless, plans were quickly made to spread Aeroflot’s wings westwards. By the end of 1945, services had been reinstated, or started anew, to most of the capitals of eastern and central Europe, and also to Teheran. At home, the trans-Siberian and other main arterial routes were revived, and the social work in the Arctic, which had continued even during the war, was maintained.

Like the British, French, and nations other than the exceptionally well-equipped United States, the U. S.S. R. had to make the best with what it had: the trusty Lisunov Li-2s and the ex-Lend-Lease Douglas C-47s.

Baidukov Has PrabBems

The Fourth Five-Year Plan had provided for ambitious Aeroflot expansion, with a target of 175,000km (110,000mi) of routes

|

The Ilyushin 18, first flown on 30 July 1947, was a 60-seat four – engined airliner which never went into production. It was too large for the traffic of the day and demanded ground support which would not be available for years, (photo: Ilyushin Design Bureau) |

throughout the Soviet Union. Yet to service this great plan, Aeroflot had little more than a large fleet of Li-2s for the main routes, and hundreds of little Polikarpov Po-2s.

This was the situation confronting Georgy Baidukov, veteran crew member of the Chkalov trans-Polar flight of 1937, and Stalin’s personal envoy to the United States during the war years, when he was put in charge of Aeroflot in 1947. The equipment upgrading prospects were gloomy. Sergei Ilyushin had made preliminary drawings for what was to become the Ilyushin 11-12 as early as 1943, and this unpressurized tricycle-geared twin made its first public appearance on 18 August 1946. But this was no ‘DC-3 Replacement’.

On the ground, airports were totally inadequate, with poor runways, bad passenger buildings, and maintenance, as often as not, in the open. Baidukov effectively made his point by taking a party of officials, including Mikoyan, on a proving flight from Moscow to Khabarovsk. The shortcomings were only too obvious, and this inspection trip no doubt had some effect on subsequent actions taken with the next Five Year Plan.

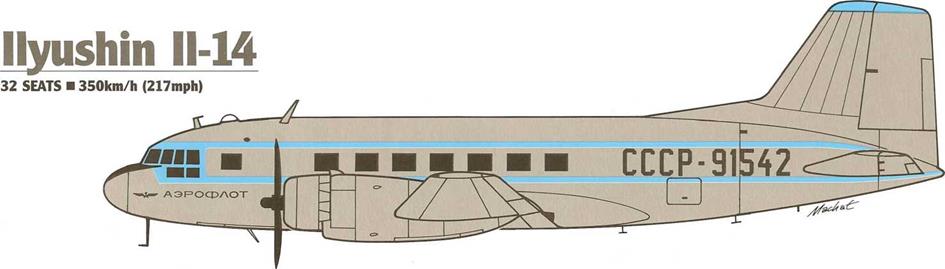

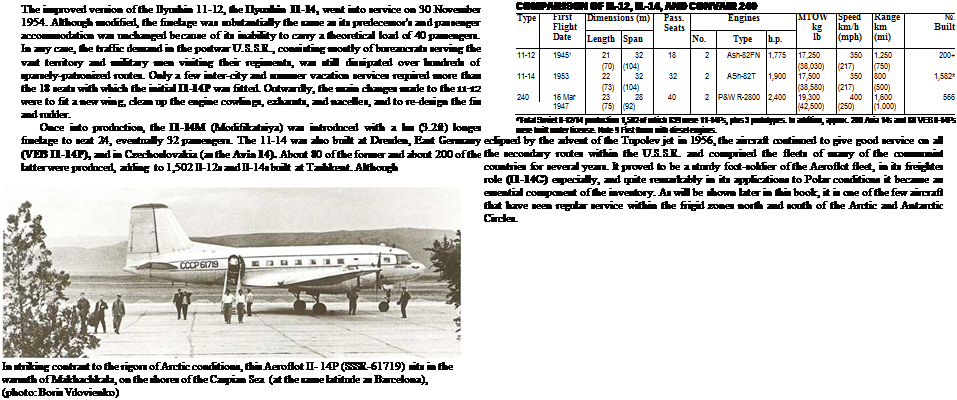

The First Ilyushins

Making the best of a sub-standard inventory, Baidukov introduced the 11-12, on a few selected routes, on 22 August 1947, and more widely in the following year when the summer schedules started on 23 May. Some relief was expected from the 60-seat four-engined Ilyushin 11-18 (the piston-engined one, not the later turboprop) but although it made its first flight on 30 July 1947, and went into service — again on selected trunk routes — at the end of 1948; it was too big and complicated for the traffic and ground infrastructure of the day, and very few were built. They were withdrawn from service by 1950.

Baidukov fought off official skepticism and introduced flight attendants on the more important routes; and he witnessed the introduction of the amazing 12-seat Antonov An-2 biplane, which made its first flight in March 1948.

Widening Responsibilities

After two and a half years, during which the Politburo often accused him of poor management, Baidukov resigned — without incidentally apologizing for anything, a procedure that was the expected protocol in those times. He had been sorely tried. For apart from the problems of inadequate aircraft, airfields, ground services and engineering staff, pilots who were apt to take on too much vodka and not enough fuel, and a meager budget, he had been given additional responsibilities.

Back in 1932, Aeroflot had taken on the task of agricultural support in crop-dusting and crop-spraying, an activity in which the U. S.S. R. had been a pioneer. In 1937, it had added ambulance and medical supply flights to supplement its other work, with a ‘flying doctor’ service. Now, on 23 September 1948, it added forestry patrol, ice reconnaissance and water-bombing; and on 30 November 1949, it was given the additional task of supporting fishing fleets by surveying the seas to locate shoals of fish.

Yet in spite of all the difficulties, Aeroflot must have been doing something right. In 1950, it carried 3.8 million passengers, and flew over a network of 75,600km (47,000mi).

18 SEATS □ 225km/h (140mph)

Shvetsov M-62 (2 x 900hp) Ш MTOW 11,280kg (24,9001b) Ш Normal Range 1,в00кт (l,000mi) Ш Length 20m (65ft) И Span 29m (95ft)

Shvetsov M-62 (2 x 900hp) Ш MTOW 11,280kg (24,9001b) Ш Normal Range 1,в00кт (l,000mi) Ш Length 20m (65ft) И Span 29m (95ft)

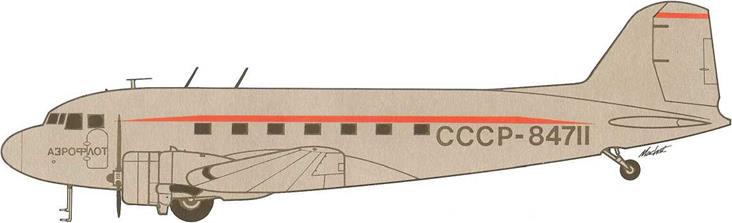

Joint Ventures

The term joint venture’ has become part of the language of international commerce during the past few years,. But such a device was common in airline associations back in the early 1940s when, for example, Pan American Airways set up such partnerships in Latin America. In exchange for certain privileges, such as exclusive mail contracts, Pan Am would provide the technical and administrative expertise, and supply aircraft at bargain rates, to set up local airlines, ostensibly as national carriers, but in reality Pan Am subsidiaries.

During the latter 1940s, as Europe rearranged itself into two halves of political persuasion, the U. S.S. R. took a leaf out of Pan Am’s book, and set up similar airlines in eastern Europe, with Aeroflot as Big Brother. Ironically, the ubiquitous Douglas DC-3, in its Lisunov Li-2 disguise, was invariably the basis of the small post-war communist-directed airline fleets, just as with Pan American on the other side of the world.

Tie First Exports

Interestingly, therefore, a California-designed aircraft, license-built in the U. S.S. R., was the key factor in this particular channel of political influence. The Lisunovs were the only aircraft in adequate supply in 1945 and 1946; but they were to be the basis for a secure Soviet foothold in what was later to become known as the Six-Pool group of eastern European airlines. This foothold was to prevail for the next half-century.

|

|

JOINT VENTURE AIRLINES IN POST-WAR SOVIET SATELLITE COUNTRIES

This Lisunov Li-2 is pictured atMirnyy, the center of the diamond industry in the Yakut autonomous republic of eastern Siberia in 1961. The ‘Russian DC-3’ performed sterling work for over a quarter of a century, and the Yakuts held it in such high esteem that they have preserved one on a pedestal at Chersky, near the delta of the Kolyma River, on the East Siberian Sea of the Arctic Ocean, 240km (150mi) north of the Arctic Circle. (Y. Ryumkin, courtesy John Stroud)

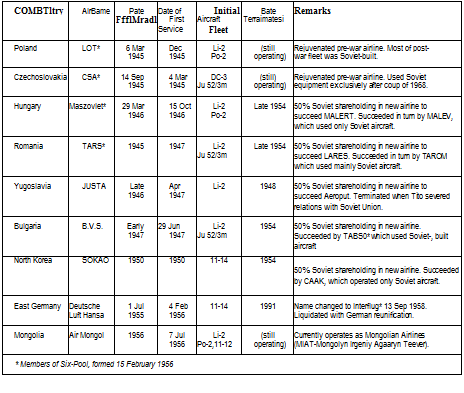

Tortoise and Hare

The Tupolev Tu-154 and the supersonic Tupolev Tu-144 both got out of the starting gate at about the same time. The trijet made its first flight on 3 October 1968, and the Soviet SST followed only three months later, on the last day of the year (see pages 64-65). The slower aircraft went into service with Aeroflot on 9 February 1972, on the route from Moscow to the health resort Mineralnye Vody. But the event was almost unnoticed while the world of aviation underwent the hypnosis of supersonic aspirations.

Workhorse

Like all new civil airliners, the Tu-154 had its problems in the early years. But Tupolev and Aeroflot pressed on with what was designed to be — to quote John Stroud — "an aircraft with the range of the 11-18, the speed of the Tu-104, and the take-off and landing performance of the An-10." Of these, only the Tu-104 was emulated in this specification, but the targets were substantially met. And, as the map on this page illustrates, the sometimes overworked equine metaphor can be for

given in its application to the aircraft that produced, by the 1990s, about half of the passenger-kilometers of the entire Aeroflot fleet, or perhaps alone as much as the total output of any one of the three leading airlines of the United States.

As Ilyushin had already found (page 55), the Kuznetsov NK-8 turbofan was a thirsty one and fuel burn could be greatly improved by replacing it with the Soloviev D-30KU as had been done in the 11-62. The Tupolev design bureau was slow to accept this possibility, and it was not until 1982, ten years after the Tu-154 entered service, that a prototype Tu-154M with derated Soloviev D-30KU engines was produced by converting a standard production Tu-154B-2. New engine nacelles were developed from those fitted to the II – 62M, with the same type of clamshell thrust reversers, and several aerodynamic improvements were made. The first two production aircraft from the Kuybyshev factory were delivered to Aeroflot on 27 December 1984, and the type remains in production.

Slow But Steady

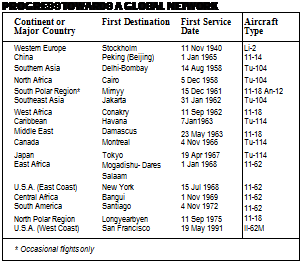

For several decades, Aeroflot was not its own master; indeed, under the Soviet system, it probably never was; but in later years, as the Cold War thawed, it acquired more autonomy and could influence the course of its own route expansion and aircraft development. In the international arena, almost a decade was to pass after the end of the Second World War before an Aeroflot aircraft was seen in western Europe, when an Ilyushin 11-12 resumed service to Stockholm in 1954. Subsequently, progress to other continents was slow.

Back in the 1920s, Dobrolet had made connections to Mongolia and Afghanistan, and experimental flights had been made to China. Now, in 1955, as the Soviet Union formed a close alliance with Mao’s People’s Republic, Aeroflot opened a link with Peking (Beijing); and the next year resumed flights to Kabul. More far-reaching tentacles reached out, with Tupolev Tu-104 service to India in 1958, to Jakarta in 1962, and Tupolev Tu-114 service to Japan in 1967. Vietnam

|

|

came on stream in 1970.

Next continent was Africa, with an Ilyushin 11-18 service to Cairo in 1958; then to West Africa, to Guinea, in 1962. During the period of the rise of African nationalism and the collapse of colonialism, the Soviet Union was anxious to capitalize (if that is the right word) on the situation; and Aeroflot was often the emissary, opening up links with Moscow throughout the 1970s and 1980s.

To The New World

These routes in the Eastern Hemisphere had been undertaken mainly with the Tupolev Tu-104 and the Ilyushin 11-18. Not until the introduction of the big turboprop Tu-114 in 1961 did Aeroflot feel confident enough, and the Soviet Union feel proud enough, to span the Atlantic. Service to Havana started in 1963 and to Canada in 1966. When the Ilyushin 11-62 was ready, Aeroflot was able to claim some slots at New York’s Kennedy International Airport.

And just as it had made its first landfall in North America in Fidel Castro’s Cuba, so it repeated the pattern by opening the first service to South America when Chile voted in a Marxist government, and Aeroflot promptly began to fly to Santiago, via Gander and Havana, in 1972. Eleven years later it started service to Buenos Aires; and later on to Nicaragua, where the left-wing Sandanistas had ousted the Somosas.

Political Ups and Downs

While in most parts of the world, politics did not interfere with, although they sometimes helped, sometimes hindered, Aeroflot’s ambitions to forge a global network. The relationship with the United States was so precariously balanced that the smooth continuance of scheduled air service between New York (and Washington, from 5 April 1974) and Moscow was never assured. In December 1981, all pretense of tolerance was thrown aside when martial law was declared in Poland, and one of the knee-jerk reactions of the Reagan administration was to terminate Aeroflot’s service to the U. S.A. Less than two years later, on 15 September, even the Aeroflot offices in the U. S. were closed down after a Korean airliner had been shot down by Soviet jets off the coast of Kamchatka.

Other countries had also imposed a ban after the ‘Flight 007’ incident, but in time the political climate eased and Aeroflot continued to build its route system. Not until 29 April 1986, however, was Aeroflot able to resume service to the States, after Presidents Reagan and Gorbachev had met in Geneva in the fall of the previous year. By 7 December 1987,

when Mikhail made a state visit to Washington, the Ilyushin I1-62M was not even remarked upon by the press. Aeroflot was part of the scene.

Polar Specialist

Not all of Aeroflot’s routes and services were politically motivated or necessarily linked with political strategy. The same could be said for the airlines of other nations, although it is arguable that Aeroflot was, as a branch of the Soviet Civil Air Administration, more directly the instrument of policy than were some other flag carriers or ‘chosen instruments’. The pioneering of some routes, however, while having certain political undertones, were just as much examples of the true spirit of airline enterprise and development.

On 10 September 1975, for example, Aeroflot opened a twice-monthly service to Longyearbyen, in Spitzbergen (Svalbard), a Norwegian territory of the Arctic on which there were two Soviet-operated coal mines. Questions were occasionally raised as to why the U. S.S. R., with all its extensive wealth of coal within its own borders, should need a couple of mines in Spitzbergen. Such suspicions aside, it did give Aeroflot, along with S. A.S., the privilege of operating to the most northerly airport in the world open to the public.

At the other end of the globe, on the opposite polar axis, Aeroflot was also active, having made its first flight to Antarctica as early as 1961 (see pages 70-71). The Soviet national air carrier thus carried the flag to every continent except Australia, and operated both to the Arctic and the Antarctic — though service to Mirnyy and Molodezhnaya was not exactly frequent, roughly once or twice a year.

Round-The-World

Aeroflot was eventually to join the ranks of those airlines that offered service completely around the world — or nearly enough to qualify for that claim. On 19 May 1991, from its well-established far eastern terminal of Khabarovsk, an Ilyushin I1-62M started service to San Francisco, via Anchorage. On 29 March 1992, this route was augmented by a direct flight, also via Anchorage, from Moscow.

Pan American Airways used to be proud of its round-the – world flights but Juan Trippe and his successors never did fill the domestic gap across the U. S.A. until it purchased National Airlines in 1978. The supreme irony was that, at the end of the same year when Aeroflot achieved round-the-world status, Pan American Airways, one of the world’s great airlines, closed its offices and terminated all its services.

No book on Russian aviation is complete without reference to the inventor Aleksander Fedorovich Mozhaisky (1825-1890). He began to study bird flight when aged 31, and during the next 20 years, experimented with models. He flew kites and designed propellers. In 1876 he himself flew in a large kite, towed by a team of three horses.

In 1877, the War Ministry granted 3,000 rubles for further tests, and on 23 March 1878 Mozhaisky outlined an ambitious ‘large apparatus’ able to lift a man. Granted a further 2,000 rubles, he traveled to England in 1880 to obtain, from R. Baker, Son, and Hemkiens, two small steam engines, one of 20hp, the other of ten. On 3 November 1981, he received a ‘Privilege’ to build his flying machine.

Parts were constructed at the Baltiisky factory at St Petersburg and assembled at the Krasny Selo military field. On 31 January 1883, he approached the Russian Technical Society with a request to demonstrate his apparatus. By the end of the year, it was moving under its own power, at least on the ground.

The fuselage and the tail, as well as the 353т^ (3,800sq ft) square planform wing, were built of wood, with steel angle brackets, and covered with varnished silk fabric, as were the three four-bladed propellers, the center one of which was 8.75m (28ft 7in) in diameter.

Some time in 1884, an unknown pilot attempted to fly Mozhaisky’s apparatus. He was launched down a sloping ramp, but failed to take to the air because of inadequate power. Mozhaisky ordered more powerful engines from the Obukhovsky steelworks, but died before the work was completed.

Other Russian scientists and inventors, such as S. I. Chernov, K. Ye. Isiolkovsky, and S. A. Chaplygin, all made considerable contributions to aeronautical knowledge during the 1890s.

Junkers leaped at the chance of taking advantage of the Treaty of Rapallo, signed on 16 April 1922, and in which Germany became the first country to recognize the Soviet Union. A production line was set up at Fili, a suburb of

Moscow, where a factory had been built in 1916 to produce the Il’ya Muromets. The Fili-built F 13s were designated Ju 13s.

During 1923, under the title of Junkers Luftverkehr Russians!, Ju 13s operated a trunk route from Moscow to Baku, on the Caspian Sea, and center of the new oil industry. It thus provided a westbound airlink, via Moscow, with Berlin, via Deruluft; and a potential eastbound connection to Persia — an intriguing aerial variant of the Drag Nacht Oosten movement that had, in 1889, seen the Sponsorship of the Baghdad Railway, in an effort to extend German influence in Asia.

German infiltration into Russian aviation dwindled by the mid-1920s. The Moscow — Baku route was taken over by Ukrvozdukhput (see next page). But Junkers aircraft were put to good use all over the Soviet Union (see also pages 20 and 24).

JUNKERS-W 33 IN SOVIET SERVICE

JUNKERS-W 33 IN SOVIET SERVICE

|

|

|

|

Shvetsov ASh-82T (2 x 1.900hp) ■ MTOW 17,500kg (38,5801b) ■ Normal Range 1,500km (930mi)

164 SEATS ■ 900km/h (580mph)

Kuznetzov NK-8-2 (3 x 9,500kg,20,9501b) ■ MTOW 90,000kg (198,4151b) ■ Normal Range 2,850km (l,770mi)

Unlikely Champion

For those interested in records, in terms of the greatest, the fastest, or the ‘mostest’, the Tupolev Tu-154 offers a fascinating exercise in statistics. The work output of the Aeroflot fleet of this type is arguably the most productive of any individual aircraft type by any individual airline in the world, measured by the standard method of calculation, based on the annual aggregate output of passenger miles.

This is not to suggest that the Tu-154 is therefore the most economical aircraft of any of its contemporary rivals. But in producing the aircraft and in operating it under the Soviet conditions of financial and operating criteria, the Tupolev Design Bureau and Aeroflot have served their country well. For offsetting the higher seat-mile costs is the excellent performance which includes the ability to take off and land at almost any reasonable airport, even those without paved runways.

THE TRIJETS COMPARED

|

First Flight Date |

First Service Date |

Aircraft Type |

Dimensions-m(ft) |

Speed km/h (mph) |

Seats |

MTOW kg (lb) |

Normal Range km (mi) |

First Airline |

No. Built |

|

|

Length |

Span |

|||||||||

|

9 Jan |

11 Mar |

DH |

35 |

29 |

930 |

84 |

59,000 |

1,900 |

B. E.A. |

117 |

|

1962 |

1964 |

Trident |

(115) |

(95) |

(580) |

(130,000) |

(1,200) |

|||

|

9 Feb |

1 Feb |

Boeing |

40 |

33 |

930 |

94 |

76,650 |

3,200 |

Eastern |

572 |

|

1963 |

1964 |

727-1 GO |

(133) |

(108) |

(580) |

(169,000) |

(2,000) |

|||

|

27 Jul |

14 Dec |

Boeing |

47 |

33 |

970 |

140 |

94,300 |

2,400 |

Northeast |

1,260 |

|

1967 |

1967 |

727-200 |

(153) |

(108) |

(605) |

(208,000) |

(1,500) |

|||

|

3 Oct |

9 Feb |

Tupolev |

48 |

38 |

900 |

164 |

90,000 |

2,850 |

Aeroflot |

1,000* |

|

1968 |

1972 |

Tu-154 |

(157) |

(123) |

(580) |

(198,415) |

(1,770) |

|||

|

Notes: |

Production continues. |

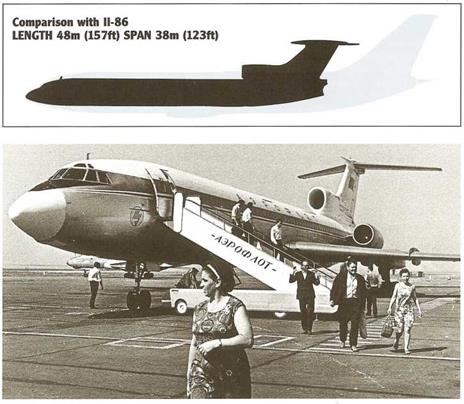

(Right) Passengers disembark from the inaugural Tu-154 flight to Simferopol, main airport for the Crimean resort area. (Boris Vdovienko)

(Right) Passengers disembark from the inaugural Tu-154 flight to Simferopol, main airport for the Crimean resort area. (Boris Vdovienko)

Supersonic Diversion

![]()

Sharing The Dream

While many in the West tended to dismiss the Tupolev Tu – 144 supersonic airliner project as being a copy of the Anglo – French Concorde, with allegations of much industrial espionage worthy of James Bond himself, the two aircraft were developed and produced simultaneously. The Tu-144, as many have surmised, was not copied, and did not follow the Concorde. In fact, it was the first to fly, and it was the first to go into service, albeit for air cargo service only, almost as a series of proving flights before the passenger service.

The Tupolev Tu-144, with its extensive use of titanium structure, and its advanced aerodynamics, gained the respect of American engineers and designers as no other Soviet aircraft had ever done before. But the Soviet supersonic program gradually lost momentum as the engineers and operator (Aeroflot) came face to face with reality; and the dream of supersonic airline schedules across the length and breadth of the U. S.S. R. faded.

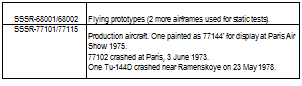

Success — and Tragedy

The Tupolev Tu-144 had its moment of glory. Test pilot E. V. Yelian made the maiden flight on 31 December 1968, a date said to have been a political imperative, to be ahead of the Concorde, which first flew two months later. Both aircraft attracted world-wide publicity but then came disaster and tragedy. At the Paris Air Show, on 3 June 1973, a Tupolev Tu – 144 disintegrated as it pulled out of a steep dive. At first thought to be structural failure, then pilot error, or a combination of both, later analysis has suggested that both pilot and aircraft could have been victims of enforced programming changes that jeopardized a well-disciplined demonstration routine. Whatever the reason, it was a shattering blow to the hopes and aspirations of the Soviet aircraft industry.

Curtailed Service Record

Nevertheless, production continued. At first wholly supportive of the SST, Bugayev, head of Aeroflot, faced formidable problems and the operation of the revolutionary aircraft

TU-144 PRODUCTION

seemed impracticable. The engines could not be programmed to operate at full efficiency in alternating subsonic and supersonic speeds; high fuel consumption inhibited long range operations; the sonic boom limited the operational scope; and the cabin noise level was unacceptably high.

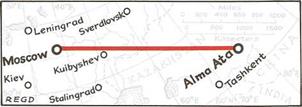

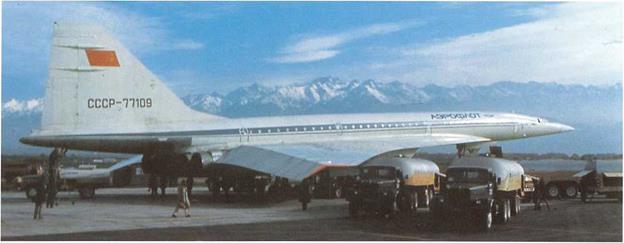

Ultimately, the entry of the Tupolev Tu-144 into airline service was almost a token gesture. Cargo flights began from Moscow to Alma Ata on 26 December 1975; passenger flights on the same route began on 1 November 1977; and these continued intermittently for only a few months before the service ended on 1 June 1978, after 102 flights. The dream had ended.

|

(Above) The Tupolev Tu-144, nose drooped, ready to take off on the inaugural passenger service from Moscow to Alma Ata on 1 November 1977. (Boris Vdovienko) |