The North Pole

The Preparations

Aviaarktika had already reached ever northwards during the late 1920s and had spread its wings far and wide across the expanses of the Soviet Union, in those areas where Aeroflot had no reason to go, for lack of people to carry in a vast mainly frigid region that was almost completely unpopulated, except for isolated villages and outposts. Rather like expeditions on the ground, such as those to the South Pole, Otto Schmidt, assisted by his deputy, Mark Shevelev, pushed further beyond the limits, very methodically.

The northernmost landfall in the Soviet Union is the tiny Rudolf Island, an icy speck on the fringes of the island group known as Franz Josef Land (named after an Austrian explorer). At a latitude of 82° North, Rudolf is only about 1,300km (800mi) from the Pole and a good location for a base camp and launching site. Access to Franz Josef Land, while haz

ardous because of the severe climate and terrain, is feasible as the twin-island territory of Novaya Zemlya accounts for about 800km (500mi) of the distance from the Nenets region.

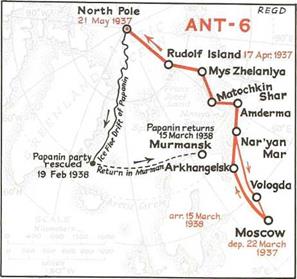

On 29 March 1936, Mikhail Vodopyanov set off with Akkuratov in a two-plane reconnaissance of the possible air route to Rudolf Island (see map). Flying blind for much of the time, and having to contend with inconveniences such as boiling six pails of water before starting the engines with compressed air, they reached their destination, and reported that the conditions, while not ideal, were not impossible. On his return to Moscow on 21 May, Schmidt was sufficiently satisfied to make plans. He arranged for the ice-breaking ship Rusanov to carry supplies to Rudolf, appointed Ivan Papanin to lead the assault on the Pole, and selected a combination of four ANT-6 (G-2) four-engined bomber transports, and one ANT-7 (G-l) twin-engined aircraft for the task. Vodopyanov was to be the chief pilot.

The Assault

The working party sent to Rudolf did their work well. In addition to setting up a base camp and a small airstrip on the

shoreline, they rolled out a longer runway, with a slight slope to assist take-off, on a dome-shaped plateau about 300m (1,000ft) above the base camp. The squadron of aircraft flew up from Moscow, leaving on 18 March 1937. Reaching Rudolf, they began final preparations. The ANT-6s were estimated to need 7,300 liters (l,600USg) of fuel for the 18-hour round-trip to the Pole, and 35 drums were needed for each aircraft. Ten tons of supplies of all kinds were to be taken, and elaborate steps were taken to design light-weight and multipurpose equipment.

There were frustrating delays, as they waited anxiously for Boris Dzerzeyevsky, the resident weather-man, to report favorable conditions, and for Pavel Golovin, pilot of the ANT-7 reconnaissance aircraft, to confirm Dzerzeyevsky’s forecasts, and to test the accuracy of the radio beacons. On one flight, Golovin was stranded for three days when he had to make a forced landing on the ice. But eventually, the expedition received the all-clear.

Flying an ANT-6 (registered SSSR-N170), Mikhail Vodopyanov, with co-pilot M. Babushkin, navigator I. Spirin and three mechanics landed at a point a few kilometers beyond the North Pole (just to make sure) on 21 May 1937, at 11.35 a. m. Moscow time. Ivan Papanin, with scientists Yvgeny Federov and Piotr Shirsov, together with radio operator Ernst Krenkel, immediately established the first scientific Polar Station (PS-1) on the polar ice, on which they eventually drifted on their private ice-floe in a southwesterly direction until they were picked up off the coast of Greenland by a rescue ship on 19 February 1938.

|

|