Opening Up The North

|

Two Soviet Worlds As Aeroflot settled down to its task of providing all Soviet citizens with an air service (see page 33), it concentrated on speeding up the journey times along the traditional main arteries that had been built by the Russian railroads to connect Moscow with all the main centers of population. Routes in European Russia extended to Leningrad, the Black Sea, the Caspian Sea, to Central Asia, and — keeping strictly to the route of the Iron Road, the Trans-Siberian Railway, to the far eastern port of Vladivostok. Except for one branch line from Irkutsk to Yakutsk, along the Lena River, the Aeroflot network was an aerial reflection of the railroad map. By the mid-1930s, this had become the framework and foundation for an ever- expanding system of air routes. In contrast, Glavsevmorput (Aviaarktika) fashioned its sorties into the far north of Russia by a different surface mode of travel. It had to; for in the 1930s, rail lines to the north ran only to Arkhangelsk and to Murmansk, the latter completed only during the Great War of 1914-1918. Instead, therefore, of following the railway lines like Aeroflot, Aviaarktika followed the rivers and waterways, the seas and the lakes; and in the summer used flying boats and floatplanes, while in the winter it exchanged the floats for skis. Only the largest aircraft, such as the ANT-6, were ever fitted with wheels. |

|

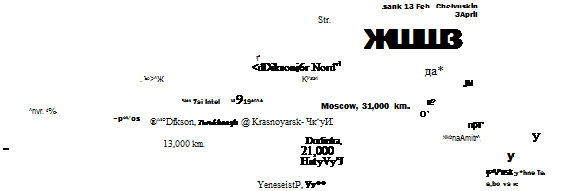

It’s a Long Way to Krasnoyarsk Vasily Molokov was one of many highly trained pilots who flew for Aviaarktika, gaining experience with every flight into the snows and the ice, the swamps and the marshlands of the northlands. He came into the public eye when, in the famous 1934 Chelyuskin rescue saga, he carried 34 people — a third of the total — to safety. The next year, on 11 February, he flew a Polikarpov R-5 from Moscow to Krasnoyarsk, on the Yenesei River, via Yanaul, near Izhevsk, and Tayga, near Tomsk. He then made a flight to the mouth of the Yenesei, at Dickson, on the Kara Sea coast, arriving on 19 March, to prove the feasibility of an air route to link important locations of mineral wealth, such as Noril’sk, with the vital Trans-Siberian trunk rail line and the Aeroflot transcontinental airway. Molokov then made two epic journeys that should rank with other great, and much better known, pioneer aerial explorations. In the first, flying a Dornier Wal, he left Krasnoyarsk on 13 July 1935, and followed various rivers to the northeast, picking up the Lena near Kirensk, thence via |

|

Yakutsk to a point near Magaden, on the Sea of Okhotsk, then to the most easterly point of Russia, at Uelen (see map), and returning along most of the north Siberian coastline, to arrive at Dudinka on 12 September. He had covered a distance of 21,000km (13,000mi). The following year, Molokov did even better. Leaving Krasnoyarsk on 22 July 1936, he followed the same route around Siberia, surveyed the Severna Zemlya islands to the far north, and flew westwards via Arkhangelsk to arrive in triumph in Moscow on 19 September. In both flights, he had followed as much as possible the courses of the great rivers and their tributaries, but east of Yakutsk, he had had to cross a formidable mountain range, between the Aldan tributary of the Lena, and the Sea of Okhotsk. From Moscow after the 1936 flight, he returned to base at Krasnoyarsk from 30 September to 5 October. The circumnavigation of Russia during the three-month odyssey covered a distance of 31,000km (16,400mi) in 200 flying hours. It was a pioneering performance of immense trailblazing significance. |

|

ANT-6 SSSR-N170, the four-engined transport that led the squadron of aircraft to the North Pole in 1937. Mikhail Vodopyanov flew Ivan Pananin and his scientific team from Rudolf Island. This picture was taken in August, when it returned to Moscow. (photo: Boris Vdovienko) |

|

)KABUL |