Following the publication of the Columbia Accident Investigation Board’s (CAIB) Final Report, NASA began preparing for the Shuttle’s Return to Flight. One idea that was developed was the idea of a safe haven on ISS for the crew of any future Shuttle that was damaged during ascent into orbit.

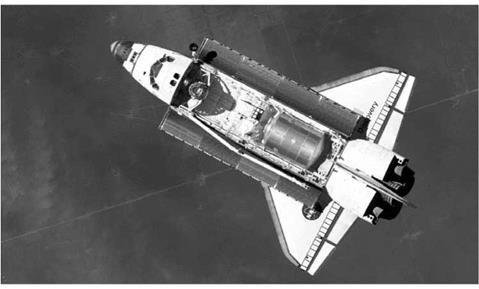

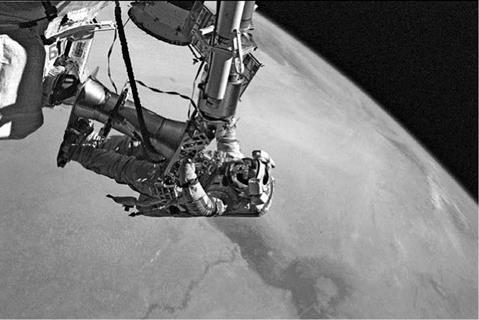

In keeping with the CAIB report’s recommendations, all future Shuttle flights would use cameras mounted on a new Orbiter Boom Sensor System (OBSS) to inspect the previously inaccessible areas of the orbiter’s Thermal Protection System (TPS). Additional photographs would be taken by the ISS Expedition crew as the Shuttle performed a nose-over-tail pitch manoeuvre prior to docking. The photographs and videos would then be downloaded to MCC-Houston, where engineers would study them and declare the TPS fit, or unfit, for re-entry. If the TPS was damaged and declared unfit for re-entry, the Shuttle crew would dock with ISS, which would then serve as a safe haven until a new means of recovery could be launched to recover them. This might be a second Shuttle, or in extreme cases, additional Russian Soyuz spacecraft.

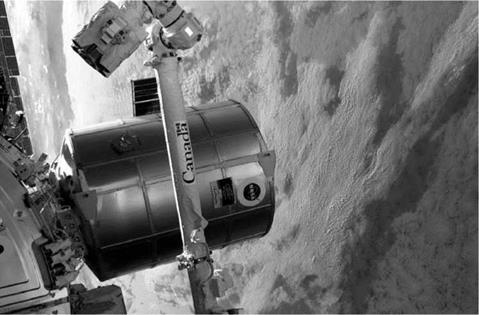

With a two-person Expedition crew and a seven-person Shuttle crew onboard, supplies available on ISS would be limited. Under existing conditions a Shuttle crew would be able to utilise the safe haven for up to 86 days, at which point NASA would have to be able to launch the rescue vehicle, a second Shuttle. Excess water and food from the crippled Shuttle would be transferred to the station to support the additional astronauts. In addition, the launch schedule for Progress cargo vehicles would have to be sustained.

|

SOYUZ TMA-3 DELIVERS THE EXPEDITION-8 CREW

|

SOYUZ TMA-3

|

|

COMMANDER

|

Michael Foale

|

|

FLIGHT ENGINEER

|

Alexander Kaleri

|

|

ENGINEER

|

Pedro Duque (Spain)

|

|

Prior to the loss of STS-107, the Expedition-8 crew consisting of Michael Foale, William McArthur, and Valeri Tokarev was due to be launched to ISS on STS-116, with a Shuttle crew consisting of:

COMMANDER: Terrence Wilcutt

PILOT: William Oefelein

MISSION SPECIALISTS: Robert Curbeam, Christer Fuglesang

STS-116 was to have returned the original (three-man) Expedition-7 crew to Earth at the end of their mission.

When the two-person caretaker crews were named on February 24, 2003, Foale and Alexander Kaleri (the third member of the original Expedition-7 crew) were named as the new Expedition-8 crew, with McArthur and Tokarev serving as their back-up crew. Spaniard Pedro Duque was flying under the Roscosmos contract that offered the third couch on a Soyuz flight to ESA if it was not filled by a commercial spaceflight participant. Duque would return to Earth in Soyuz TMA-2 with the Expedition-7 crew. Foale was on his sixth spaceflight, Kaleri his fourth, and Duque his second.

Discussing his training for flying the Soyuz spacecraft during his various crew allocations, Foale has said:

“Well, I’ve had a lot of experience, compared to other U. S. astronauts training for Soyuz flight. First of all, on Mir we had to train for Soyuz emergency descent, and that was basically as a passenger cosmonaut-astronaut in the right seat. On this last training flow before Columbia I was training for the left seat emergency descent with a cosmonaut in the center seat. After Columbia, Sasha and I were named to be the backups to Ed Lu and Yuri Malenchenko that are on orbit right now, and there I had to train both for launch in the left seat, rendezvous, and then descent. And then at the same time I had to take the same classes that Sasha, the Commander, was taking and do those in the centre seat. So I have seen the whole smorgasbord of crew roles and responsibilities on board the Soyuz.’’

Asked about the possibility that he might also have to return to Earth in a Soyuz spacecraft at the end of the Expedition-8 crew’s occupation, Foale remarked:

“I think, to be quite honest, I’d like to come home in the Soyuz. And that’s mostly because it’s well understood right now. Its ballistic entry was demonstrated by Ken Bowersox and Don Pettit and Nikolai Budarin on the last entry. People called that off-nominal—it certainly was not an expected entry—but it demonstrated yet another aspect of the Soyuz, which is its robustness… [H]owever, I do want the Shuttle to succeed… But I don’t believe… that the Shuttle’s architecture will allow it to be significantly safer without adding crew escape to it.’’

Soyuz TMA-3 was launched at 01: 38, October 18, 2003. Kaleri served as Soyuz Commander, with Foale assuming command only after entering the station. Docking to Pirs nadir occurred at 03 : 16, October 20, as ISS passed over Central Asia. Meanwhile, in orbit, pressure and leak checks were followed by the opening of the hatches between the two spacecraft at 05: 19, and the new crew entered the station, where the

Expedition-7 crew, who were on their 177th day in space, greeted them. The flags of Spain and ESA were displayed on the station alongside those of America and Russia. After eating lunch, the three newcomers received the standard safety brief before Duque’s couch liner was transferred to Soyuz TMA-2. Meanwhile, NASA announced details of two minor problems with the flight. The potentially more serious of the two was a small helium leak between the helium pressurisation tank and the propellant tanks of Manifold 2 in the Soyuz propulsion system. Manifold 1 would be used for the remainder of the Soyuz TMA-3 flight.

After Soyuz TMA-3 had safely docked to Pirs, the Washington Post released details of how two “mid-level scientists and physicians” had refused to sign the initial approval for the launch due to their concerns over the deterioration of environmental monitors and the medical and exercise equipment on ISS. The report also claimed that ISS was running low of medicines and intravenous fluids, and the noise levels in the Russian sector of the station were greater than desired, and required a noise – deadening programme. NASA Administrator Sean O’Keefe stated publicly that the he did not believe the crew to be in any danger. Both the Expedition-7 and Expedition-8 crews acknowledged the difficulties, but stated that they believed they were in no immediate danger. These reports led to a number of politicians jumping on the bandwagon and using the incident as an excuse to attack NASA and its Administrator. Representative Sheila Jackson Lee (Democrat-Houston) stated, “Safety, above all, has to be the highest priority. After the Columbia Accident Investigation Board’s report came out, I asked specifically about the safety of the Space Station and the response coming back was not as strong as I wanted. Now it seems there is not only a problem, there is a crisis.’’ NASA also had its supporters, Dana Rohrabacher, head of the House Space and Aeronautics subcommittee, told the press, “I have faith Mr. O’Keefe is doing his best and shouldn’t be second-guessed by politicians.’’ Meanwhile, the two individuals concerned told the media that they had not identified any immediate threats to crew safety, but were concerned over the deterioration and long-term failure of equipment measuring the environment on the station since the loss of STS-107, and the grounding of the Shuttle fleet. They stated that they had spoken to NASA officials from JSC and were content that NASA was taking their concerns seriously and had begun to address the issues that they had raised.

When the issues were first raised and became public, in the second week of October, O’Keefe had been blunt. He told the media that if the situation reached a point where the crew was at risk then.. the answer is, get aboard the Soyuz, turn down the lights and leave.’’

Docking was followed by 8 days of joint operations, with Malenchenko and Lu handing over to Foale and Kaleri, while Duque performed his “Cervantes” experiment programme. This consisted of 24 experiments to be completed, in both the Russian and American sectors of the station, over 40 hours. Foale described his feelings on what would happen during the hand-over in the following terms:

“[Tjhere are a number of goals to be achieved during the joint operations… of the oncoming crew and the off-going crew. First and foremost … Spain, through ESA… are paying the lion’s share of this Soyuz flight, and they have serious

|

Figure 41. Expedition-8: Michael Foale and Alexander Kaleri pose alongside the mess table in Zvezda.

|

science objectives to accomplish during the five days that Pedro is planned to be on board the Station with us. And so, to be honest… I feel obliged, just as Sasha does, to help Pedro get kicked off to a running start as soon as we arrive. There is nothing more important than getting Pedro running. The remaining four days I will spend my time with Ed Lu, and I hope to learn everything he has learned about the Destiny module, about the Airlock, the Node, and all of our stowage there and all of our equipment there, and its operations with the control center here in Houston. However, I must not ignore what’s going on in the Russian segment, where Sasha Kaleri will be spending a lot of time with Malenchenko and learning about Russian operations, work in the Service Module and in the FGB, and in their docking module… By the time four days have gone by, I will know just the bare minimum to be able to find my clothes, wash my body, do my exercise, and work the radio… but the practical knowledge will be there after four days. And at that point, we will be ready to say, Pedro, you’re going to that spacecraft; your seat liner’s in that spacecraft—the old one, the returning one— with Ed Lu and Yuri Malenchenko, and then we’ll close the hatch and breathe a sigh of relief, because joint ops is a very hard time because everybody has a lot to do in a short time.’’

The ceremonial change of command ceremony took place on October 24. Three days later Malenchenko and Lu and Duque sealed themselves in Soyuz TMA-2. They

|

Figure 42. Expedition-8: Launched with the Expedition-8 crew, Spaniard Pedro Duque participated in an ESA experiment programme before returning to Earth with the Expedition-7 crew.

|

were preparing to undock when the complex rolled unexpectedly. This caused the thrusters on Zvezda to fire, to correct the station’s attitude. NASA described the incident:

“At 2.57 pm, while ISS was in the XPOP momentum management mode, the station experienced a large unexpected roll manoeuvre event, with momentum increasing from 16 percent to 90 percent in four minutes. As 90 percent triggers a de-saturation of the CMGs, with Service Module thrusters, several de-saturation burns followed, using several kilograms of propellant. Proper attitude control was re-established for the undocking… Troubleshooting by Moscow determined that the cause of the torque was a crewmember, during ingress, contacting the Soyuz hand controllers, which are not supposed to be active at that time. TsUP further determined that the override commands to activate the hand controllers were inadvertently initiated by a Soyuz control panel pushbutton, while the crew was loading return items.’’

As usual TsUP had managed to put the blame on the crew, despite the fact that no one in the Russian control room had noticed that the Soyuz hand controllers had been inadvertently activated.

Soyuz TMA-2 undocked at 18: 17, October 27. The de-orbit burn took place at 20: 47, and the re-entry module touched down on target in Kazakhstan at 21: 41. The

Expedition-7 crew had spent 184 days 22 hours 46 minutes and 9 seconds in flight. Duque had been away from Earth for 9 days 21 hours 1 minute 58 seconds. Initial medical examinations at the landing site showed all three men to be in good health, but the Expedition-7 crew underwent the usual 45-day rehabilitation programme at Korolev, where Malenchenko’s new wife was waiting to welcome him back to Earth.