PROGRESS M-58

Progress M-58 was launched from Baikonur at 09:41, October 23, 2006 and climbed into orbit. The spacecraft performed a standard rendezvous before docking to Zvezda’s wake at 10: 29, October 26. As Progress M-58 approached Zvezda, telemetry failed to confirm that a KURS antenna on the front of the spacecraft had retracted as scheduled. If it had not retracted then it would interfere with the docking latches. Following soft-docking, Russian controllers in Korolev spent 3.5 hours trying to confirm the antenna had retracted. During this period the station’s attitude control systems were powered off and the station was allowed to drift so as not to disturb the Progress vehicle and misalign it. In this period the station’s drift led to a misalignment of the SAWs and a drop in electrical power. Following routine procedures, the crew powered off non-critical items to conserve power. Finally, the docking probe on the Progress was retracted and the docking latches engaged, securing a hard-dock at 14: 00. After hard-docking, the station’s attitude control systems were powered on and the station brought back to its correct attitude. The non-critical items were then powered on once more. Among its 2,393 kg of cargo, Progress M-58 carried replacement parts for the Elektron oxygen generator as well as 2.5 tonnes of food, water, propellant, oxygen, spare parts, supplies, and personal items for the crew.

The non-confirmation of the KURS antenna folding on the new Progress continued to worry Russian controllers in Korolev and they began planning a Stage EVA to confirm it was correctly stowed. Lopez-Alegrla and Tyurin would make the EVA on November 22. Tyurin would also hit a golf ball away from the Pirs docking compartment in a commercial “experiment” designed to result in the longest golf strike in history. Meanwhile, Reiter began packing material planned to be returned to Earth on STS-116, the Shuttle flight that would bring his 6-month stay on ISS to an end. As the preparations for the next Shuttle launch continued, the Expedition-14 crew continued with their experiments. In preparing for their EVA, Lopez-Alegrla and Tyurin attached American EVA lights to the helmets of their Orlan pressure suits. Meanwhile, controllers in Houston continued to test CMG-3, which had shown unplanned vibrations prior to being shut down on October 9. Tyurin repaired the Elektron unit in Zvezda on October 30, after which it was powered on and began supplying oxygen to the station’s atmosphere once more.

Lopez-Alegrla walked the SSRMS end over end from its position on the exterior of Destiny to the MT, which had been positioned at Workstation 4 on the ITS, on November 1. After manoeuvring the SSRMS so that both end-effectors could be photographed, the MT was moved to the far end of the P-4, where the SSRMS would be used to install the P-5 ITS during the flight of STS-116. Meanwhile, Reiter began preparing for his return to Earth. He would be relieved by American Sunita Williams. Even so, the European experiment programme on ISS continued unabated. The Elektron unit malfunctioned again, developing an internal water leak on November 7. Five days later, the crew began shifting their sleep pattern to match that of the STS-116 crew, then due for launch on November 22. They also closed the hatches between Pirs and Progress M-57.

At 19:17, November 22, Lopez-Alegria and Tyurin exited Pirs wearing Orlan suits. Expedition-14’s first Stage EVA began 1 hour late, after Tyurin had to deal with a pinched cooling hose in his suit. He had had to climb out of his suit and reposition the hose in order to release the pinch. Having re-entered the suit, closed the hinged Portable Life Support System behind him, and repressurised the suit he was finally ready to proceed. Once outside, Tyurin mounted a З-gramme golf ball on a spring mounted tee which he attached to the ladder on the exterior of Pirs. With his booted feet on the ladder he used a gold-plated six-iron to strike the ball away, towards Zvezda’s wake. Tyurin remarked, “There it goes, and it went pretty far, I can still see it as a little dot, moving away from us.’’

Controllers estimated that the ball would re-enter the atmosphere and burn up in three days. Tyurin said he was pleased with the shot and controllers chose not to have him make a second shot. The golf shot was paid for as a commercial venture by a Canadian golf company.

Moving to Zvezda’s wake, where Progress M-58 was docked, Tyurin attempted to release a latch on the KURS antenna that had failed to retract. Despite his best efforts using both his gloved hands and a crowbar, alongside commands radioed up from Korolev, the antenna continued to refuse to retract. The two men took a series of digital photographs, which would show that the antenna’s dish was stuck behind one of Zvezda’s EVA handrails. A tool to remove the antenna would be delivered on STS-116. Moving on, the two men relocated a communications antenna that would be used by the European ATV. By moving the antenna just 0.З m from its original location it no longer impeded the cover of one of Zvezda’s rocket motors. It was this antenna that had prevented an attitude control burn taking place on April 19, 2006, because the cover on the rocket motor could not be opened to its full extent. At Zvezda’s ram they installed the BTN-Neutron experiment, designed to record the flux of neutron particles found in low-Earth orbit following solar particle events. Their final task was to jettison a pair of thermal covers for the experiment. The EVA ended after 5 hours З8 minutes.

The last week of November was spent preparing for the arrival of STS-116, Discovery. The Expedition-14 crew prepared Quest for three planned EVAs and they prepared the equipment that would be returned to Earth. On November 29, Tyurin changed out batteries in both Zvezda and Zarya. On the same day, an attempt to re-boost the station using the thrusters on a Progress spacecraft was cut short due to a software problem. Over-sensitive software shut down the thrusters after detecting motion caused by the planned manoeuvre. The planned 18-minute 22-second burn lasted just З minutes 16 seconds. The manoeuvre was completed on December 4, and placed ISS in the correct orbit for Discovery’s rendezvous.

Tyurin and Reiter disassembled the Matryoshka human torso experiment in Pirs, to remove the З60 internally mounted radiation sensors. They also removed the KURS avionics packages from Progress M-57 and Progress M-58 and stowed them for return to Earth.

As November ended, the US National Research Council released a report criticising NASA for failing to obviously redirect the ISS science programme to meet the needs of Project Constellation, and in particular human flights to Mars, saying, “The panel saw no evidence of an integrated resource utilization plan for the use of the ISS in support of the Exploration Missions.” It continued, “The ISS may prove the only facility with which to conduct critical operation demonstrations needed to reduce risk and certify advanced systems.”

|

STS-116 DELIVERS “PUNY”

|

In the wake of a December 7 launch attempt that had been cancelled, due to low cloud, the fact that the ET had been filled with fuel demanded that the next launch attempt could not take place for a further 48 hours. On the second attempt, STS-116 lifted off from Kennedy Space Centre at 20: 47, December 9, 2006. In the minutes before launch, Polansky told the launch team, “We look forward to lighting up the night sky.” It was the first Shuttle night launch in over four years. He also told the media, “There are always inherent risks when you take people off the planet and try to propel them a couple of hundred miles into space. We try to mitigate the risk as much as possible. If anyone says we can take all the risk out, they are just blowing smoke.”

Fuglesang was pragmatic, saying, “I hope this will increase interest in space for Sweden, and actually for science and technology in general. This flight is a small step in the assembly of the Space Station. The station is a small step toward the Moon and Mars.”

Meanwhile, Space Station Manager Mike Suffrendi told a press conference, “Many of us consider this the most challenging Space Station flight we’ve done since we began the assembly effort. When the Shuttle leaves, ISS will not look much different than when Discovery got there, but it will be a dramatically different vehicle inside.’’

Discovery’s seven-person crew would complete three EVAs, during which they would install the port-5 (P-5) ITS and then re-wire the station’s electrical system, bringing on-line the SAWs delivered by STS-115. Sunita Williams would join Expedition-14 crew members Lopez-Alegria and Tyurin, while Thomas Reiter would return to Earth in Discovery with the STS-116 crew. The Shuttle also carried a SpaceHab pressurised module full of equipment and supplies for the station. Asked about the mid-term hand-over Lopez-Alegria explained:

“Well, I think it all stems from the notion that the Russian Space Agency,

Roscosmos, would like to have the third seat in the Soyuz available for a paying

passenger… and so the third person can’t rotate there and he or she will rotate on Shuttle. So, that’s… the scheme that we have evolved to.’’

He continued:

“I think there are certain disadvantages, certainly. If you were to build a true Expedition crew, you’d like them to be sort of lockstep with each other all the time. I think this is a little bit different because we do have a fair amount of access to the ground, talking to people, e-mailing friends and family, using the internet protocol phone to be able to converse with people. That probably eases the difficulty in being isolated somewhat that is so specific to certain types of expeditions. I think that the result is that the need to bond really as a single unit is not as stringent as it might be if we were going to live that kind of an experience. However, it does bring up some interesting challenges. I think there’s also some advantages because six months with the same two faces all the time, if you don’t like one of those two faces it could get old. At least, in this fashion, we will have the opportunity to change those faces once in a while.’’

Commander of Expedition-15 Fyodor Yurchikhin would express a different point of view, which I quote on p. 277.

On reaching orbit, Discovery was configured for flight and her payload bay doors were opened to expose the vital radiators mounted on their interiors. During the first day in orbit the crew powered up the RMS, and lifted the OBSS from the payload bay door hingeline. They then used the OBSS cameras and lasers to inspect Discovery’s heatshield and the leading edges of the wings. Houston confirmed, “There is nothing anyone is excited about so far.’’ The crew also installed the usual selection of rendezvous equipment and cameras and checked the EMUs they would wear during their three EVAs.

Following a standard rendezvous. Williams got her first view of the station and reported excitedly, “Tally-ho on my new home. It’s beautiful. The solar arrays are glowing.’’ After the now routine r-bar pitch manoeuvre, Discovery docked to ISS at 17: 12, December 11. As usual, the station’s bell was rung to welcome the visitors. Following pressure checks, the hatches between the two spacecraft were opened and the Shuttle’s crew were welcomed aboard the station at 18: 54. As the hatches were swung open Lopez-Alegria joked, “We’re having a ball already.’’

The first order of business was to inspect the tip of Discovery’s port wing with the cameras on the RMS, after a vibration was picked up by the wingtip sensor 18 minutes after docking. The additional inspection delayed the crew using the RMS to un-berth the P-5 ITS from its position in Discovery’s payload bay. The P-5 ITS was subsequently handed over from the Shuttle’s RMS to the SSRMS and was then positioned over Discovery’s port wing, where it was left overnight. Williams described the P-5 ITS in the following terms:

“P-5 (and S-5) is a part, that goes between the two major solar array wings. Without them, the two wings would be too close together to actually operate.

|

Figure 78. STS-116 crew (L to R): Robert L. Curbeam, William A. Oefelein, Nicholas J. M. Patrick, Joan E. Higginbotham, Sunita L. Williams, Mark L. Polansky, Christer Fuglesang. |

|

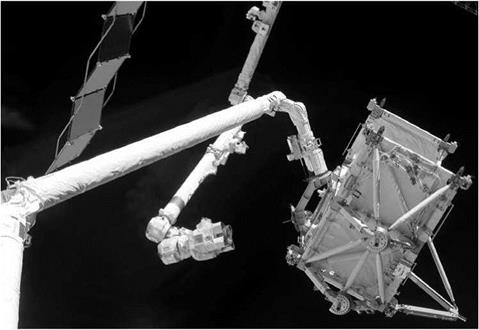

Figure 79. STS-116: astronauts operating the Shuttle’s RMS prepare to pass the P-5 Integrated Truss Structure over to the station’s SSRMS for installation on the station. |

They’re a pass-through for all of the thermal, electrical lines going out to the end of the truss and absolutely critical… to make sure that the two big solar array wings will be able to operate.’’

At 01:00, Williams installed her couch liner in Soyuz TMA-9 and transferred her Sokol pressure suit from Discovery, thus transferring herself to the Expedition-14 crew. At the same time Reiter transferred his equipment to Discovery and became part of the STS-115 crew. For her first two weeks on the station Williams would spend 1 hour each day, in order to familiarise with the station and the Expedition-14 crew’s routines. These hours were unstructured, allowing Williams to concentrate on whatever she felt was necessary to bring her up to speed. Williams has described the advantages of a mid-term crew exchange:

“I think I’m really lucky… they’re going to be there to help me with any… turnover things that I don’t understand. I’m a rookie; never flown before. These two are both experienced space fliers; and them, having lived there for about three months before I get there, I think if I have any questions, they’ll be the perfect people to show me the way.’’

Prior to retiring for the night, the STS-116 crew reviewed the procedures for their first EVA, planned for the following day. Curbeam and Fuglesang sealed themselves in Quest and reduced the pressure in order to “camp out’’ in the airlock overnight, as part of their EVA pre-breathing regime.

Williams, who would operate the RMS during the P-5 installation, explained:

“The first EVA, which is the P-5 install. Me and Joanie Higginbotham will be operating the robotic workstations. We’ll be taking the P-5 Truss from a handoff position from the Shuttle robotic arm and we’ll be moving it to the end of P-3/P-4 for the installation. It’s a little bit of a tricky installation because the clearances to get the P-5 into its position are pretty tight, about three inches or so. Some of the issues with that is the P-3/P-4 solar array wing is live at the time, so there’s going to be some black boxes on the end of P-3/P-4 that are live powered. And so with that clearance, the biggest worry is that you don’t hit the box that has the live power on it, ’cause that’s going to cause a lot of problems. So, we’ve practiced this very intensely with the spacewalkers Bob Curbeam and Christer Fuglesang. They’ll be out on opposite ends of the P-3/P-4 truss, guiding us in. So this is a very complicated, entire-crew-involved event to try to get this guy installed… Part of that EVA is also starting up the main bus power switching units, MBSU, and while we’re making sure that that’s all starting up correctly, the two space- walkers, Bob Curbeam and Christer Fuglesang, will be moving the CETA carts to the opposite side that they’re on, in preparation for the next solar array, which is the S-3/S-4 installation. So, we’ll be working with the spacewalkers again as we’ll be picking them up and driving them over to the truss, while they’ll be grabbing on to the CETA carts. We’ll be flying them over to the other side of the MBS.’’

The first EVA began at 15:31, December 12, when Curbeam and Fuglesang transferred their suits from external power to internal batteries. Exiting Quest, they prepared their tools and then made their way across to the P-5 ITS. The two astronauts guided Higginbotham as she lifted the P-5 ITS into its installation position at 17:45. With the new ITS section in place, the two EVA astronauts bolted it into position, completing the task at 18: 21. Moving on, the two astronauts replaced a failed camera, removed the launch restraints and an RMS grapple fixture from the P – 5 ITS as well as a cover that would allow the P-6 ITS to be bolted to it when it relocated from its present position on the Z-1 Truss’ zenith. With the two astronauts back inside the airlock the EVA ended at 22:07, after 6 hours 36 minutes. During the day mission managers confirmed that Discovery’s heatshield was in good condition for re-entry at the end of the flight.

After a night’s sleep, phase two of the flight’s objectives got underway. The crew spent 6 hours, beginning at 18: 17, December 13, sending a series of over 40 commands to retract the port SAW on the P-6 ITS, which had been in place on the station since it was deployed in 2000. The retraction did not go well and the arrays had to be partially retracted, re-deployed, and retracted again. Despite everything, they failed to retract as planned. The guidewires became snagged with only 17 of 31 panels retracted, but it was enough to allow the day’s work to continue. At 20: 00, the P-4 SAWs began rotating to their operational position. When the ITS was complete and all the SAWs were deployed, they would be able to rotate to track the Sun as ISS orbited Earth. On the evening of December 13, 2006, P-4 became the first SAW to rotate. The manoeuvre was completed without difficulty, and just before 23: 00 the valves were opened to allow ammonia to flow into the ITS and the huge radiators mounted there. This was the first stage towards providing permanent cooling for the avionics and electronics on ISS. Inside, the two crews spent the day transferring equipment from Discovery’s SpaceHab module and mid-deck to the station.

Meanwhile, in Houston, mission managers met to discuss the various options for completing the retraction of the P-6 SAW. One option was to assign additional EVA tasks, to be performed by the Expedition-14 crew after Discovery’s return to Earth, in order to carry out the task manually. The meeting concluded that the partially retracted P-6 port array was in a safe configuration to be left for the remainder of the STS-115 flight and, if necessary, the arrival of the next Progress, planned for launch in January 2007. Despite the difficulties with the P-6 SAW the management team agreed to proceed with the second EVA as planned. As a result, Curbeam and Fuglesang spent a second night camping out in Quest under reduced atmospheric pressure. The two crews began their sleep period leaving the P-4 array rotating as it tracked the Sun and the ammonia flowing through the new cooling system, while they slept. Attempts to transfer orientation of the station back to the CMGs failed, possibly due to increased atmospheric drag as a result of increased solar activity. Discovery remained in control of the combination for the time being.

December 14 began with a planned major power-down of many of the ISS’ electrical systems. The systems were powered down because the electrical system that supplied them with power was about to be switched from the P-6 ITS SAWs to the P-4 ITS SAWs. Orientation of the Shuttle/ISS combination was controlled by

Discovery, which maintained orientation by firing the orbiter’s thrusters as demanded by its own attitude control system. Curbeam and Fuglesang began their second EVA at 14:41, approximately 30 minutes ahead of schedule. During their 5-hour EVA they worked swapping cable connectors to establish the station’s permanent cooling and power systems. By 16: 30, one of the external cooling loops was shedding heat into space and the direct-current-to-direct-current converter units were regulating electrical power. By 16: 45, controllers were applying power to Channels 2 and 3 for the first time. Additional tasks included relocating one of the CETA handcarts that would run along the ITS. Having caught up a further 30 minutes by performing their tasks more quickly than planned, the two astronauts returned to Quest and ended their EVA at 19: 41. Williams and Higginbotham had operated the SSRMS throughout the EVA.

December 15 was a day of internal work. During the first half of the day the crews transferred equipment between the two spacecraft. Following that work they performed two press conferences before taking the remainder of the day off. At 21: 04, Williams commanded the stuck P-6 SAW to deploy slightly and then retract by the same amount. The attempt left the SAW in exactly the same position as it was when she started, with just 17 of its 31 panels folded. In Houston, mission managers were still discussing the possibility of a fourth, unplanned EVA to try to complete the folding up of the P-6 SAW. Curbeam and Williams camped out in Quest during the night with the pressure reduced, in preparation for their third EVA the following day.

The flight’s third EVA began at 14: 25, December 16, but not before controllers in Houston had shut down half of the station’s electrical systems: the opposite half to that shut down on December 14. Curbeam and Williams left Quest and prepared their tools. They spent their time swapping electrical connectors once more to bring the station’s electrical system to its final configuration. In future, when additional ITS elements were added no new reconfiguration of the electrical and cooling system would be required, except to connect the new ITS elements to the existing system. By 16: 18, controllers in Houston were applying power to Channels 1 and 4 for the first time, as they brought the station’s electrical and cooling systems back on-line. Their primary task complete, the two astronauts fitted a grapple fixture to the SSRMS and positioned three bundles of radiation shielding for the Russian sector on the exterior of the station. The shielding would be installed in its final locations on a later EVA. Their final task was to position themselves on either side of the partially retracted P-6 photovoltaic array and take turns to shake their respective sides of the SAW while their colleagues inside the station attempted to retract it. Looking at the guidewires on the SAW, Curbeam reported, “It’s definitely hanging up.’’ He shook the array and it cleared temporarily allowing it to be further retracted before it snagged again. It was a frustrating procedure that had to be repeated several times.

“This is definitely the right approach. I think we are starting to get there,’’ encouraged Lopez-Alegria from inside the station.

In the control room in Houston, Steve Robinson watched the live television pictures and remarked, “That is an impressive amount of motion and very effective.’’ Curbeam replied, “I’m here to serve.’’

Curbeam shook the array 19 times and Williams 13 times while the retract command was issued 8 times. At the end of their efforts only 11 panels on the array remained unfolded. The EVA ended at 21:56, after 7 hours 31 minutes.

Whilst the third EVA was underway, mission managers in Houston confirmed that Discovery’s flight would be extended by one day to allow Curbeam and Fuglesang to make an unscheduled fourth EVA, in an attempt to finish the retraction of the P-6 SAW.

Working inside the station on December 17, the crews were slightly ahead of schedule in their work to transfer equipment between the two spacecraft. As a result, they spent much of the day preparing for the fourth EVA. Work included positioning the SSRMS and Discovery’s RMS to support the EVA. Cameras on the latter would be used to video the astronauts’ actions. Discovery’s crew also transferred two EMUs to Quest for use during the EVA. Curbeam and Fuglesang spent the night camped out in Quest with the airlock’s pressure reduced.

Curbeam and Fuglesang left Quest at 14: 12, December 18. Having collected their tools Curbeam mounted the SSRMS and was lifted over to the balky array. Fuglesang made his way manually to the P-6 ITS. Curbeam would attempt to free the stuck guidewires and push on hinges to ensure that they folded the correct way while Fuglesang would stand behind the “blanket box’’, into which the array was being folded and push it in an attempt to encourage retraction. With the manual work onsite completed controllers in Houston sent commands to retract the SAW one panel at a time. The SAW was finally fully retracted at 18: 54, and the two blanket boxes were locked at 19: 34. The EVA ended at 20: 50, after 6 hours 38 minutes. In making this unscheduled EVA, Curbeam became the first Shuttle crewmember to make four EVAs during a single flight.

During the farewell ceremony held on the station as Discovery’s crew prepared to return to Earth, Polansky said, “It’s always a goal to leave a place in better shape than it was when you came. I think we have accomplished that.’’

Williams told Reiter, “I hope Discovery takes you home as smoothly and safely as it brought me here.’’

With Oefelein at the controls Discovery undocked from ISS at 17: 10, December 19, and completed a half-circuit fly-around before finally manoeuvring away. During the fly-around the crew photographed the station in its new configuration. On the following day, Polansky, Oefelein, and Patrick used the RMS-mounted OBSS to survey Discovery’s heat protection system. The remainder of the crew began stowing equipment for landing. On the ground, NASA’s Phillip Engelhauf remarked, “We are assuming the vehicle is in a ‘go’ condition for landing unless somebody illuminates an issue out of that data. The assumption is that everything is fine.’’

At 19: 19, December 20, a pair of coffee cup-size Micro-Electromechanical System Based PICOSAT Inspector (MEPSI) satellites were launched from Discovery’s payload bay as a single unit, which then separated into its component parts. The technology was designed to allow similar satellites to photograph/film the larger vehicle from which they are launched. A pair of Radar Fence Transponder (RAFT) satellites were launched from the payload bay at 20: 58, the same day. They were designed by a group of students at the US Naval Academy to test the American

|

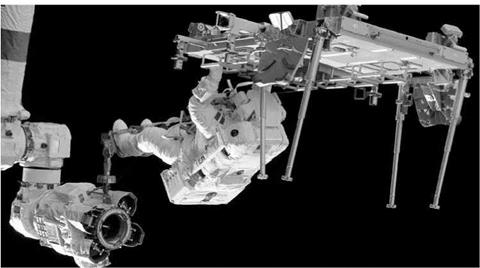

Figure 80. STS-116: Christer Fuglesang rides the SSRMS to relocate a Crew Equipment Translation Aid (CETA) cart on the Integrated Truss Structure. |

|

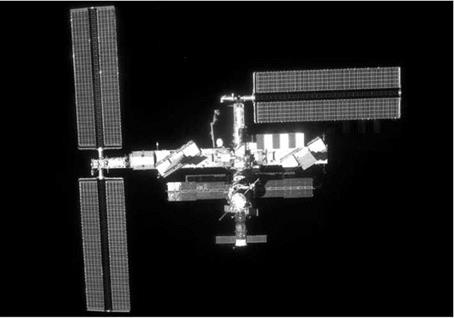

Figure 81. STS-116: as the Shuttle departs the station its lop-sided configuration is obvious. The S-4 Solar Array wings are shown at left and one set of the P-6 Solar Array wings are deployed. The other set of P-6 Solar Array wings were folded and stowed by the STS-116 crew in anticipation of the P-6 Integrated Truss structure’s relocation in 2007. The P-5 ITS is partially hidden behind the P-1 ammonia radiators. |

Space Surveillance Radar Fence designed to identify hostile objects approaching the continental United States from space.

Preparations for returning to Earth began in earnest on December 21. Oefelein and Curbeam tested Discovery’s aerodynamic surfaces and manoeuvring thrusters. Polansky and Oefelein practised simulated landings on a laptop computer. At 12: 23, Fuglesang and Higginbotham launched the Atmospheric Neutral Density Experiment (ANDE) micro-satellite from Discovery’s cargo bay.

On December 22, the first opportunity to land at KSC was waved off due to the stormy weather conditions there. An opportunity to land at Edwards Air Force Base, California was also waved off due to gusty winds. As the day continued weather in Florida improved and Discovery was able to utilise the second landing opportunity at that site. Polansky glided his spacecraft to a perfect touchdown, just after sunrise, at 05: 32, having spent 12 days 20 hours 44 minutes in flight. Reiter had been in space for 171 days. NASA Administrator Michael Griffin was present to greet the crew. He told the assembled crowd,

“This was a big year… I’ve said if we could take the time to get things going properly, we could get back to an operational tempo and finish the station by the time it’s necessary to retire the Shuttle… We have a new understanding in this country that each and every time we do this, it’s a minor miracle.’’

On returning to JSC, Polansky told gathered workers and their families, “It’s awesome to see so many people. This is not about us, it’s not about this crew. This is about everybody that shares the same dream, the same drive and really believes in what we are doing with human space flight.’’