Recovery and restructuring

|

STS-121 RETURNS THE SHUTTLE TO FLIGHT

|

STS-121 was the first Shuttle flight since the fleet had been re-grounded in the wake of STS-114. The flight would carry 4,000 kg of cargo to the station in the MPLM Leonardo, to re-stock the supplies that had been used during the intervening period. It would also deliver Thomas Reiter, the third member of the Expedition-13 crew, to the station. Reiter was the first ESA astronaut to serve on an ISS Expedition crew. The agreement to fly Reiter was signed in May 2003. Director of Human Spaceflight at ESA Daniel Sacotte explained:

“It covers the ESA astronaut’s flight in a crew position originally planned for a Russian cosmonaut. He will perform all the tasks originally allocated to the second Russian cosmonaut on board the ISS and, in addition, an ESA experimental programme.’’

Reiter added:

ESA is making important contributions to the ISS and its scientific capabilities. We are assuming significant operational responsibilities in this programme and I am confident that this mission will give Europe valuable

operational experience and scientific results which will further prepare us for the exciting and challenging times ahead.”

STS-121 would be the first launch to be controlled from the new Firing Room 4 in the Launch Control Centre, at KSC. The new Firing Room would become the principal launch control room for the remainder of the Shuttle programme, while the original Firing Rooms were converted for use in Project Constellation.

The first attempt to launch STS-121 was made on July 1, 2006. On that occasion the countdown reached the planned hold at T — 9 minutes, when it was held due to anvil clouds, potential thunderstorms, in the area. The launch was subsequently scrubbed and recycled to the following day. On July 2 the countdown was scrubbed for a second time, due to anvil clouds in the area and recycled for a further 48 hours. The new launch date was set for July 4.

On July 4 a crack in the insulating foam on the Shuttle’s ET had to be filled and an investigation was required when a triangular piece of foam fell away from the ET while Discovery stood on the launchpad. It was decided that the launch could proceed as planned. In February, Lindsey had warned the media, “We will lose foam on this flight, just like every other. The key is to make sure that any foam we do lose is of a small enough size so it can’t hurt us if it hits the vehicle.’’

Discovery finally lifted off at 14: 38, July 4, 2006 and was in orbit a few minutes later. Film from the numerous cameras on the vehicle showed that the ET had continued to shed foam and the crew were even informed that MCC-Houston thought that one piece might have struck the underside of the orbiter. The crew began their sleep period at 20: 38.

Eight hours later, they were awake and ready for their first full day in space. Beginning work shortly after 07: 00, Nowak and Wilson used the RMS to lift the

|

Figure 70. STS-121 crew (L to R): Thomas Reiter, Michael E. Fossum, Piers J. Sellers, Steven W. Lindsey, Mark E. Kelly, Stephanie D. Wilson and Lisa M. Nowak. |

OBSS from the opposite edge of the payload bay and manoeuvred it so that the Laser Dynamic Range Imager, the Laser Camera System, and the Intensified Television Camera mounted on the end could image the leading edge of both wings and the orbiter’s nosecap. Meanwhile, Sellers set up Discovery’s computers and Reiter prepared the mid-deck for the transfer of equipment and stores to ISS. Sellers and Fossum were assisted by Kelly as they checked the EMUs they would wear on two, or possibly three EVAs.

On ISS, Vinogradov and Williams prepared cameras, with the 400 mm and 800 mm lenses, that they would use to photograph Discovery during its approach to the station. They also pressurised PMA-2 in preparation for Discovery’s docking.

As Discovery approached ISS, Lindsey commenced station-keeping at a distance of 200 metres, he then performed a nose-over-tail pitch manoeuvre so that Vinogradov and Williams could photograph the underside of the orbiter. The photographs were down-linked to Houston for scrutiny. The rendezvous then continued and Lindsey docked Discovery to PMA-2 at 10:52, July 6. Following pressure checks the hatches between the two vehicles were opened and Discovery’s crew entered the station at 12: 30. Vinogradov and Williams greeted them and then issued the standard safety briefing. Williams told Houston, “It’s a full house. The climate has changed significantly.” The first action after that was to transfer Reiter’s couch lining and Sokol pressure suit from Discovery to Soyuz TMA-8, thereby signalling his transfer from the STS-121 crew to the Expedition-13 crew. For the first time since the Expedition-6 crew, who had been in orbit when STS-107 was lost in February 2003, the Expedition crew on ISS now consisted of three people. Vinogradov had the following to say about the arrival of the European astronaut:

“I think that it is a very important milestone… at this stage we can support a crew of three or more. But from the human standpoint, it’s important because we do have to notice that over the last two years the ISS program is kind of slowing down and the interest is not what it used to be on the part of the Russian government and Congressmen in the United States. There are certain notes of dissatisfaction on the part of the people who are working on the science and experiments on board the station because unfortunately the rate of station assembly and deployment is quite different from what they expected. And so the arrival of the third person, Thomas Reiter in our case, greatly improves the capability of the crew in terms of performing science program and experiments. The other thing is that Thomas Reiter is a representative of Europe. Europeans are important and we are working with them very closely. The European Space Agency contributes considerable effort from the standpoint of research.’’

Williams was equally keen to see Reiter join the crew:

“We’re really looking forward to the Shuttle arriving, and Thomas joining us as a crew of three. It’s obviously very significant. Since Expedition 7 we’ve been flying and sustaining the Space Station with a crew of two. Those who track that sort of thing say that it takes more than two people just to run the station, so it leaves no excess crew time for the other things. Getting back to a crew of three will help us accomplish more. It’s also significant in that we will be continuing with the assembly of the Space Station, to get it up to its full capability with the resuming of regular Space Shuttle flights, which is important, of course, to meet the vision of space exploration.”

The EMUs that Fossum and Nowak would use during their planned EVAs were also transferred, from Discovery to Quest. In preparation for the first EVA, Williams and Wilson used the SSRMS to lift the OBSS from its storage position and hand it over to Discovery’s own RMS. With Discovery docked to ISS there was insufficient clearance for Discovery’s RMS to retrieve the OBSS. During the EVA, the 33-metre long combination would undergo tests as a work platform giving access to areas of the Shuttle that were previously inaccessible.

The following day, Nowak, Wilson, Fossum, and Sellers used the SSRMS to lift Leonardo out of Discovery’s payload bay and dock it to Unity. Docking occurred at 08:15, July 7, following an initial concern that straps on Unity’s CBM might prevent a perfect air-tight seal. Following pressure and leak tests Lindsey, Wilson, and Reiter opened the hatches between the two modules and began several days of equipment transfer. Vinogradov was in no doubt of the importance of the arrival of Leonardo at the station:

“That period of joint flight with the Shuttle is quite busy in terms of the crew of the station and the Shuttle crew working together. It’s quite intense work. First you have to move a very considerable amount of cargo, you have to get it out of the MPLM and stow it on the station. It’s quite important—extremely important, I would say—because that provides the supplies for our continued flight.’’

Williams has said:

“It’s also important to get a lot of the equipment that is no longer required on station off and packed into that empty MPLM so it can come home. The station’s getting pretty crowded here in recent months and years… It’s going to be important for both crews to be very disciplined in the transfer of equipment, both to the station and returning to the Shuttle. To do that, we have a flight plan onboard. Part of that flight plan is a transfer plan. It’s a detailed choreography of all of the transfers, everything that goes across the hatches between the Shuttle and the Station, developed by the folks on the ground and trained by both crews.’’

Nowak, Kelly, and Wilson also used the RMS/OBSS combination to carry out further inspections of Discovery’s exterior, finding six areas requiring further investigation, although none of them were areas of major concern. Areas of particular attention were parts of the nosecap that had been missed on July 5, and a piece of fabric near the orbiter’s nose. Fossum and Sellers spent the day preparing for their first EVA. During the day, mission managers made the decision to extend Discovery’s flight by one day, including a third EVA. Engineers in Houston also reviewed the initial photographs and laser scans of Discovery’s exterior.

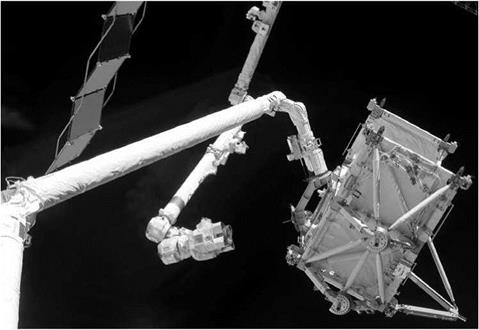

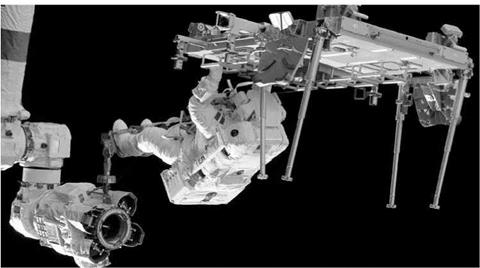

EVA-1 began at 09:17, July 8, when Sellers and Fossum left Quest. Their first task was to repair the MT mounted on the S-0 ITS. The emergency cable cutter had malfunctioned and cut one of two cables that moved the MT along the truss. During a Stage EVA the Expedition-12 crew had removed the second cable from the cutter after failing to install a bolt to prevent the blade from falling and cutting it. After collecting their tools together, Sellers and Fossum made their way to the S-0 ITS, where they installed a device to block the cable cutter blade on the MT, thereby denying the ability to sever the cable in an emergency. After installing the block, they reinstalled the cable in the cutter, thereby repairing the MT and making it available to move the SSRMS along the truss during EVA-2. The second portion of EVA-1 included simulating the use of the RMS/OBSS as a workstation. Nowak and Wilson operated the RMS from Discovery’s aft flight deck, while Kelly served as intravehicular officer, the EVA astronauts’ guide, offering whatever assistance he could from inside Discovery. With Sellers standing on the foot restraint mounted on the end of the OBSS the combination was put through a series of pre-planned manoeuvres while sensors recorded the forces involved. Sellers remarked, “Just a general comment. It gets easier as you go along doing all the tasks on the end of a skinny little pole. A little practice makes perfect.’’ In Houston the Flight Director commented at his end-of-shift press conference, “The arm damped a lot quicker than we thought, based on our analysis… That gives us very good confidence we could use this as a platform for repairs.’’ In space, Fossum joined Sellers at the end of the OBSS, which was then manoeuvred to three different simulated work positions. The last of these lifted Fossum to a position where he could push up with his hands against the P-1 ITS. The EVA ended at 16:48, after 7 hours 31 minutes.

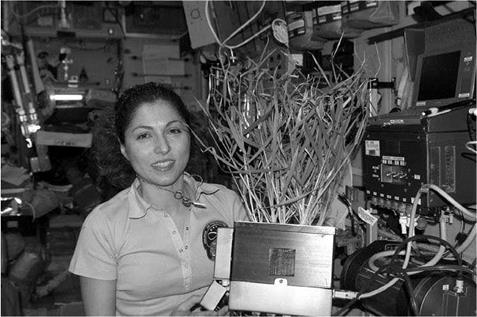

While the EVA was taking place, Vinogradov and Reiter began unloading Leonardo and transferring stores to the station, including a new sample freezer and a new oxygen generator. When installed in Destiny, at a later date, the generator would upgrade the station’s oxygen capacity to the point that it could support up to six people on long-duration Expedition crews.

As the day’s activities came to an end mission managers cleared Discovery’s heatshield for re-entry. The following day, July 9, was spent unloading stores from Leonardo and preparing items on Discovery for return to Earth. Sellers and Fossum spent the day cleaning their EMUs and preparing their tools and Quest for their second EVA, on July 10.

With the crew awake at 02: 08, preparations for the second EVA began immediately after breakfast. Sellers and Fossum left Quest at 08: 14, and climbed down into Discovery’s payload bay. There, they lifted the pump module from its stowage location so that Nowak and Wilson could grapple it with the SSRMS and lift it into position. Meanwhile, Sellers and Fossum remained in the payload bay preparing for the primary task of the EVA, replacing the Mobile Transporter’s Trailing Umbilical System (TUS), the power and data cable that had been cut during the Expedition-12 occupation. Both men made their way to the S-0 ITS, where Fossum disconnected electrical cables, and Sellers then replaced the Interface Umbilical Assembly (IUA) with a new one, without a cutting blade. By that time the SSRMS had manoeuvred the pump module to External Stowage Platform 2. Sellers and Fossum made their

way to that location and secured the module to the platform, thus allowing the SSRMS to release it. The pump module was a spare, now available if it should be needed in the future.

Sellers and Fossum returned to their work on the TUS. Now working from the end of the SSRMS, Fossum removed the TUS reel assembly and carried it down to the payload bay. While he was doing that, Sellers worked in the payload bay to unpack and prepare the new reel assembly. While Fossum returned to the work site Sellers stowed the old reel assembly in Discovery’s payload bay. Back on the S-0 Truss, Fossum was joined by Sellers and they worked together to install the new reel assembly and routed it through the IUA. The work ensured that the MT would have the required redundancy to enable it to support future assembly flights. Having stowed their equipment, both men returned to Quest and the EVA ended at 15: 01, after 6 hours 47 minutes. During the EVA Fossum had to twice stop working and secure a loose connection on Seller’s SAFER. While the work was taking place outside, Vinogradov, Williams, and Reiter continued to unload Leonardo, and Lindsey transferred two bags of water from Discovery to ISS.

The following day, July 11, was spent transferring equipment and rubbish from ISS to Leonardo, for return to Earth. Wilson served as loadmaster, ensuring everything was secured in the correct place, thereby retaining Discovery’s correct centre of balance for re-entry and landing. Sellers and Fossum cleaned their EMUs and prepared them for their third EVA.

That EVA began at 07: 20, July 12. Sellers and Fossum left Quest, made their way into the payload bay, collected their tools, and installed a foot restraint on the SSRMS. After Sellers had mounted the SSRMS, Nowak and Wilson manoeuvred him to a point close to Discovery’s starboard wing’s leading edge, where he recorded several seconds of infrared imagery. The imagery, which recorded temperature differences, would help to identify any internal damage to the area. The manoeuvre simulated lifting an astronaut to a position where he could try to repair damage to the wing’s leading edge, as suffered by STS-107. Returning to the payload bay, Sellers joined Fossum at a workstation where both men trialled a variety of methods for repairing damage to 12 samples of Reinforced Carbon-Carbon, similar to the panels on the wing’s leading edge. Using a space-cleared caulking gun and a series of spatulas, they pumped a carbon-silicon polymer called NOAX into the simulated damaged tiles in an attempt to repair them. Over almost two hours they repaired three gauged tiles and two cracked tiles. They also imaged four of the repair samples with the same infrared equipment that Sellers had used of the starboard wing. An additional get-ahead task was added to the EVA: Sellers used a pistol grip tool to remove the fixed grapple bar used to move the pump module during the second EVA, moved over to the S-1 Truss, and installed it on an ammonia tank that was due to be moved during the Expedition-15 occupation. The EVA ended at 14: 31, after 7 hours 11 minutes. As usual, the remainder of the crew spent the day loading Leonardo.

Following their hectic first eight days, Discovery’s crew were given July 13 off, with the exception of a few interviews. July 14 was also spent in interviews and completing the final loading of Leonardo. The MPLM was de-activated and was undocked from Destiny at 09: 32, and lowered into Discovery’s payload bay, where it

|

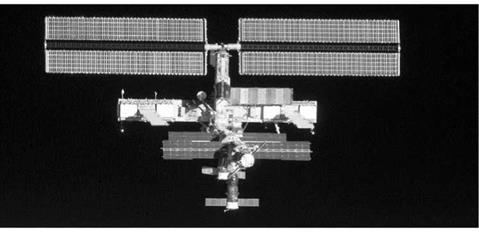

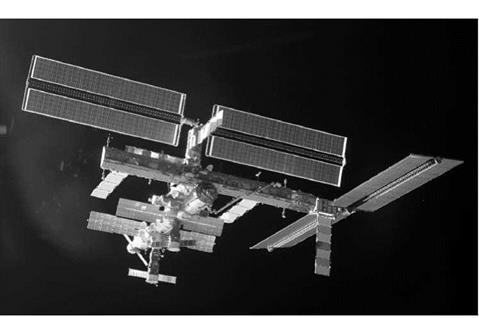

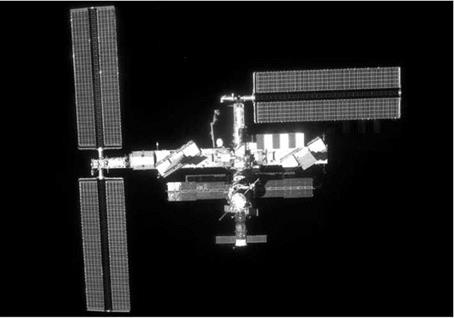

Figure 71. STS-121: A view from the station’s wake, as STS-121 completes its fly-around, shows the station as it was before construction was resumed. |

was secured at 11:00. Lindsey and Reiter then used the RMS, with the OBSS attached, to view Discovery’s heatshield and search for any damage that had occurred during orbital operations. None was found.

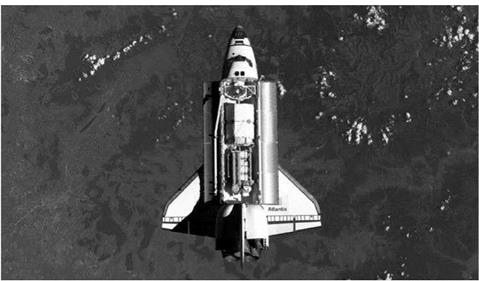

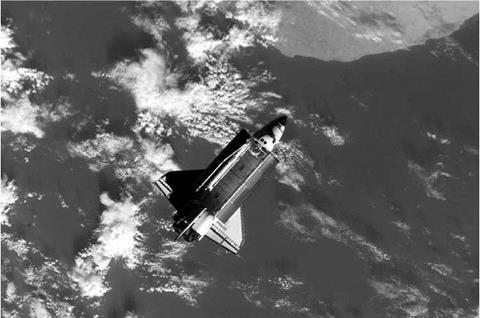

July 15 was the final day of joint operations as Discovery’s crew prepared for their departure. Undocking took place at 06: 08 and was followed by the crew imaging the leading edge of the starboard wing and the nosecone. Discovery performed station-keeping while mission managers reviewed the new images and cleared the heatshield for re-entry. The Shuttle fell behind and above ISS with the minimum of manoeuvring. Discovery’s crew spent the following day preparing for re-entry, while, on ISS, Williams depressurised PMA-2 and Vinogradov and Reiter continued the station’s maintenance and experiment programmes.

Discovery’s payload bay doors were closed at 05: 27, July 16, and retrofire occurred at 08: 07. Thereafter, Lindsey turned his vehicle so the nose was forward and high, until gravity pulled it out of orbit. The orbiter glided to a perfect landing at KSC, at 09: 15, after a flight lasting 12 days 18 hours 38 minutes. It had six astronauts onboard, one less than at launch; the seventh, Reiter, was still in orbit, as part of the now three-person Expedition-13 crew.

At the landing site Michael Griffin told the press, “Obviously this is as good a mission as we’ve ever flown… But we’re not going to get overconfident.” The Shuttle was finally back in business and the construction of ISS was set to continue. Meanwhile, NASA was already busy defining the vehicle that would replace the Shuttle when it retired in 2010. When the crew returned to Houston, Lindsey told the waiting crowd, “In terms of human spaceflight… we’re back.’’ The crowd applauded loudly. Lindsey was more sombre, “I think it’s more like the beginning of the next phase… I don’t think we ever want to put Columbia behind us.’’

As Discovery landed, the published flight programme for the completion of ISS looked like this:

|

Launch date |

Flight |

Vehicle |

Flight details |

|

August 28, 2006 |

12A |

Atlantis STS-115 |

• Second port truss segment (ITS P-3/P-4) • Second set of solar arrays and batteries |

|

December 14, 2006 |

12A.1 |

Discovery STS-116 |

• Third port truss segment (ITS P-5) • SpaceHab Single Cargo Module • Integrated Cargo Carrier (ICC) |

|

February 22, 2007 |

13A |

Atlantis STS-117 |

• Second starboard truss segment (ITS S-3/ S-4) with Photovoltaic Radiator (PVR) • Third set of solar arrays and batteries |

|

June 11, 2007 |

13A.1 |

Endeavour STS-118 |

• SpaceHab Single Cargo Module • Third starboard truss segment (ITS S-5) • External Stowage Platform 3 (ESP3) |

|

Under review |

ATV1 |

Ariane 5 |

• European Automated Transfer Vehicle |

|

August 9, 2007 |

10A |

Atlantis STS-120 |

• Node 2 • Sidewall, Power and Data Grapple Fixture (PDGF) |

|

September 27, 2007 |

1E |

Discovery STS-122 |

• Columbus European Laboratory Module • Multi-Purpose Experiment Support Structure, Non-Deployable (MPESS-ND) |

|

November 29, 2007 |

1J/A |

Endeavour STS-123 |

• Kibo Japanese Experiment Logistics Module, Pressurized Section (ELM-PS) • Spacelab Pallet, Deployable 1 (SLP-D1) with Canadian Special Purpose Dexterous Manipulator, Dextere |

|

February 7, 2008 |

1J |

Atlantis STS-124 |

• Kibo Japanese Experiment Module Pressurised Module (JEM-PM) • Japanese Remote Manipulator System (JEM-RMS) |

|

June 19, 2008 |

15A |

Endeavour STS-119 |

• Fourth starboard truss segment (ITS S6) • Fourth set of solar arrays and batteries |

|

August 21, 2008 |

ULF2 |

Atlantis (last flight) STS-126 |

• Multi-Purpose Logistics Module (MPLM) |

|

Under review |

3R |

Russian Proton |

• Multipurpose Laboratory Module with European Robotic Arm (ERA) |

|

Launch date |

Flight |

Vehicle |

Flight details |

|

October 30, 2008 |

2J/A |

Discovery STS-127 |

• Kibo Japanese Experiment Module, Exposed Facility (JEM-EF) • Kibo Japanese Experiment Logistics Module, Exposed Section (ELM-ES) • Spacelab Pallet, Deployable 2 (SLP-D2) |

|

January 22, 2009 |

17A |

Endeavour STS-128 |

• Multi-Purpose Logistics Module (MPLM) • Lightweight Multi-Purpose Experiment Support Structure Carrier (LMC) • Three crew quarters, galley, second treadmill (TVIS2), Crew Health Care System 2 (CHeCS2) |

|

Establish six-person crew capability |

|||

|

Under review |

HTV-1 |

H-IIA |

• Japanese H-II Transfer Vehicle |

|

April 30, 2009 |

ULF3 |

Discovery (last scheduled flight) STS-129 |

• EXPRESS Logistics Carrier 1 (ELC1) • EXPRESS Logistics Carrier 2 (ELC2) |

|

July 16, 2009 |

19A |

Endeavour STS-130 |

• Multi-Purpose Logistics Module (MPLM) • Lightweight Multi-Purpose Experiment Support Structure Carrier (LMC) |

|

October 22, 2009 |

*ULF4 |

Discovery STS-131 (if needed) |

• EXPRESS Logistics Carrier 3 (ELC3) • EXPRESS Logistics Carrier 4 (ELC4) |

|

January 21, 2010 |

20A |

Endeavour STS-132 |

• Node 3 with Cupola |

|

July 15, 2010 |

*ULF5 |

Endeavour STS-132 (if needed) (final Shuttle flight) |

• EXPRESS Logistics Carrier 5 (ELC5) • EXPRESS Logistics Carrier 1 (ELC1) |

|

ISS assembly complete |

|||

|

Under review |

9R |

Russian Proton |

Research Module |

|

* Two Shuttle-equivalent flights for contingency. Notes’. Soyuz flights for crew transport schedule at approximately 6-month intervals beginning in September 2006. Additional Progress flights for logistics and re-supply are not listed. |

At the Farnborough International Air Show, in England, held during July 2006, ESA Director Jean-Jacques Dordain stated at a press conference, “I have a wish that Europe participate in one of the two next-generation transportation systems [the American Orion, or Russia’s Kliper]. If we don’t, I fear we will always be a second – class partner.” America had already made it clear that NASA intended to develop Orion as an all-American spacecraft, so ESA had agreed to undertake a 2-year feasibility study on crewed spacecraft architecture, for a spacecraft to be launched by a Soyuz launch vehicle from Baikonur, or from the new pad for such vehicles at ESA’s launch site in Kourou. Meanwhile, Energia had to admit that Kliper would cost more than the entire Russian space programme budget for the period 2006-2015. Therefore, the new spacecraft would not be built. Rather, the Russians would update Soyuz yet again, making it capable of Earth orbital and lunar orbital flight. At the same meeting NASA Administrator Michael Griffin explained to the audience, “Our plan is to have one more daylight [Shuttle] launch before resuming night operations … We do need to resume night operations to complete the Space Station, we’ve always known that.’’

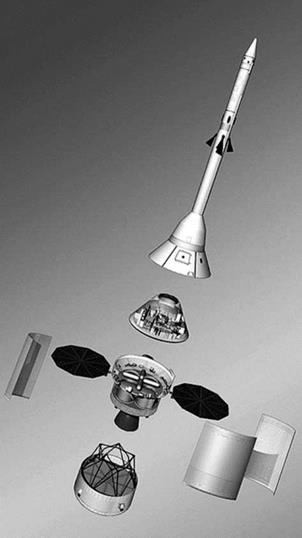

In America, NASA had named the two new Shuttle-derived launch vehicles that would be used to support Project Constellation. The Crew Launch Vehicle would be called Ares-1 and the Heavy Lift Launcher would be Ares-5. The numerical designations were salutes to the Apollo Saturn-class launch vehicles. Meanwhile, the CEV had been named “Orion”. Lockheed-Martin was named as prime contractor for the development of the Orion spacecraft in August 2006. It would be a ballistic capsule, superficially similar to the Apollo Command Service Module, and would carry a crew of up to six people. It would be launched by an Ares-1 launch vehicle consisting of a first stage derived from a Shuttle SRB and a new liquid propellant second stage. The new vehicle would use the old Apollo/Shuttle facilities at LC-39, KSC.

NASA had also launched a quest for commercial cargo access to ISS, the Commercial Orbital Transportation Service (COTS). Two industry partnerships, led by SpaceX and Rocketplane Kistler, would use NASA funding, along with private funding to develop an automated vehicle to deliver cargo to ISS and to carry away rubbish. The new vehicle would be heated to destruction during re-entry. The selected developer would be open to sell space on their vehicles commercially, and NASA would be nothing more than a commercial customer. Flight demonstrations would begin in 2008. Phase-1 development would concentrate on an uncrewed cargo vehicle, with the option to progress to Phase-2, a vehicle for delivering humans to ISS.