A CONTRACT IS AWARDED

Meanwhile, at McDonnell’s Advanced Design Department, Luge Luetjen said everyone had “hit the ground running" and the place was a beehive of frantic activity.

“The dynamics and aerodynamics people had developed the equations for the ascent trajectory, the orbital flight, and descent trajectory of a typical space vehicle. Working with the engineers in the computer lab, we managed to set up a program such that with any combination of the independent variables (thrust, weight, flight path angle, etc.) the characteristics of the flight could be determined, printed out, and plotted. The results obtained were critical for the structural, heat protection, and aerodynamic design of a spacecraft. Considerable research had been done by Max Faget and others at the NACA Langley Field facility on various spacecraft body shapes and their characteristics. They shared this information freely with all that were interested, and some of us spent considerable time in conference with them on the subject. The ‘wheels’ in the department, but mostly Yardley, had decided that we would bundle all our studies and calculations in a single report whose format was similar to what we thought that of a Request for Proposal (RFP) for a manned space vehicle might be. As it turned out, we didn’t have long to wait.”8

Even while Robert Gilruth’s STG team was still designated as part of NACA, it began work on the writing of detailed specifications for a Mercury capsule. By the end of October 1958 a preliminary draft had been completed.

On 7 November, two days after the official formation of the STG, a briefing of potential bidders for the contract to develop and construct a manned spacecraft was held at the Langley Research Center, where the STG was initially based.

Of the 40 companies in attendance, 20 later indicated that they were prepared to bid for the contract, and were given the preliminary specifications. A week later, on 14 November, NASA had received firm offers from all 20 companies – including McDonnell – to bid on the project. Three days after that, the final documentation, Specification No. S-6 “Specifications for Manned Spacecraft Capsule,” was mailed out to the interested parties. The deadline for the return of their proposals was set at 11 December.

“Our report was pretty much on target,” according to Luetjen, “and we had little trouble transforming our information into a proposal required to be submitted by December 11. We had our proposal quickly completed and simply spent the remainder of the time double checking and dotting the i’s and crossing the t’s.”9

Of the 20 companies that expressed further interest in submitting bid proposals, only 11 actually followed through. In turn, NASA passed these bids on to the STG for assessment. The people at McDonnell were delighted subsequently to learn that when the contender numbers were narrowed by almost half, their company was still in the running. After all their hard work in putting the proposal together, several employees took accrued vacation time in order to be ready to resume work if (or more optimistically, once) they learned their bid had been successful.

Over the Christmas break the STG conducted a scrupulous evaluation of all the proposals and finally narrowed their choice down to the one contractor they felt best qualified from the standpoint of technical abilities, ideas, and approach to the issue. Over in Washington, D. C., meanwhile, NASA officials were also scrutinizing the proposals, conducting an evaluation of the business and management aspects of the twelve bidders.

In January 1959, after Administrator Keith Glennan had reviewed the NASA evaluation, the space agency opened further negotiations with McDonnell as the potential prime contractor. On 12 January, shortly after the McDonnell workers from the Advanced Design Department (Space) had returned from their Christmas and New Year break, all of the department’s workers were called to a meeting in Mike Weeks’ office where he told them that James McDonnell had been informed by NASA’s Space Task Group that following an evaluation of all the submitted proposals, McDonnell Aircraft had been named as the winner of the contract and negotiations would begin immediately for the design, production and support of twelve Mercury spacecraft.

“No one in Advanced Design slept much on Monday night after Mike Weeks’ announcement of our winning the Mercury competition,” Luetjen recalled. “Each individual was trying to determine what the next move in their expertise should be. As I remember, early on Tuesday, Yardley got the group together and indicated that most, though not all, of those who had worked on the proposal would be joining him on the project. Some of the pure scientists would remain in Advanced Design to do spade work on projects beyond Mercury.

“The early task facing each of the prime systems engineers was two-fold: to work with their NASA counterpart to roughly define their system such that specifications could be drafted on which subcontractors/suppliers could bid; and secondly, to estimate the effort and material costs to consummate their part of the program such that a basic contract could be agreed upon at an early date. It greatly helped that much coordination and contact with potential suppliers had taken place prior to the submission of our proposal. Two main systems were unsettled when it came time to sign the contract, and the contract wording had to be sufficiently loose to allow alternatives. It was yet to be determined whether the heat protection system should consist of a beryllium heat sink or a shield made of a material that would ablate and thus dissipate the heat upon reentry, and secondly, it was unknown at that juncture whether the escape system should be a rocket boost system to separate the spacecraft from the launch vehicle or a rocket pull system in which the escape rocket would be mounted on a tower on the forward (small) end of the capsule.”10

According to Max Faget, the Atlas rocket had been chosen as the most suitable booster for the later orbital missions. “Bob Gilruth came in one day and says, ‘Max… what are you going to do if the Atlas blows up on the way up?’ And I didn’t have an answer for that. And he said, ‘Well, you’d better get an answer for it.’ I’ve always said that was an invention on command. It was very fortunate that one of our colleagues, Woody Blanchard, again in the Pilotless Air Research Division, had been experimenting with tow rockets. He put canted nozzles on a rocket and towed models, research models, up to Mach 1 and above, but instead of pushing, he’d pull them. So knowing that you could do [that with] the rocket up front, it was just a small step instead of putting a cable up there, to put a structure up there that would hold it rigidly during launch but be in place whenever you need it. That turned out to be a very successful thing.”11

An initial contract for the construction of 12 similarly constructed spacecraft was formally signed on 6 February. This number was subsequently increased to 18, and then to 26, before finally being set to 20 as the development effort matured. During the

|

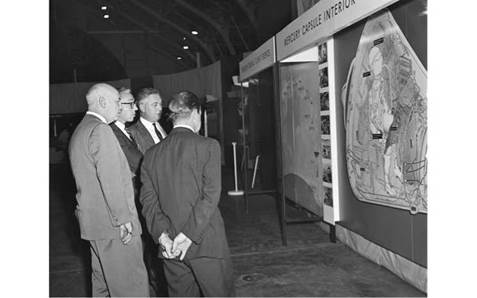

Robert Gilruth (left) views an engineering diagram of the Mercury capsule, along with D. Brainerd Holmes, Director of NASA’s Office of Manned Space Flight; Walter Williams, Operations Director; and John (‘Shorty’) Powers, Public Affairs Officer. (Photo: NASA) |

negotiations, officials from McDonnell estimated it would be possible to deliver the first three capsules within ten months.

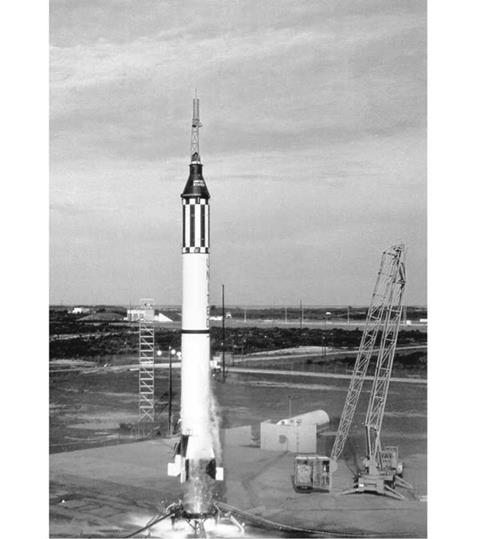

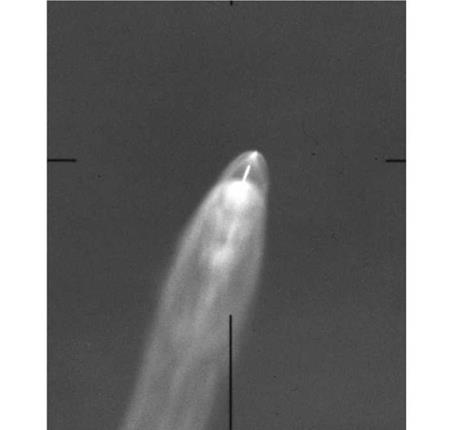

As Robert Gilruth noted in his unpublished memoirs, “During this same period of time we established an arrangement with the Ballistic Missile Division of the Air Force for the procurement of the Atlas launch rockets and for launch services. We [also] worked out a plan with [Major] General [John B.] Medaris [commanding the Army Ballistic Missiles Agency] and Dr. [Wernher] von Braun [of that agency] for the Redstone launch vehicles, and we started work in our own staff for a design and specification for the Little Joe rocket to be used in tests at Wallops Island. We gave to Lewis the job of creating a full-scale Mercury model spacecraft for an unmanned flight at an early date to establish levels of heat transfer and stability in a full-scale free-flight test on an Atlas booster at Cape Canaveral…. The project was started in December 1958 and flew successfully in September 1959.”12