The flight of Liberty Bell 7

It was Friday, 21 July 1961, a morning that was almost a carbon copy of Wednesday prior to scrubbing the launch due to poor weather conditions. For the second time in less than 48 hours, Gus Grissom removed his protective overshoes and was carefully assisted into Liberty Bell 7 at 3:58 a. m. (EST), hoping to keep his delayed date with history.

A MORNING FILLED WITH OPTIMISM

The U. S. Weather Bureau meteorologists had once again been keeping a close eye on the weather, and especially the areas of low pressure. They kept NASA’s flight director informed about conditions not only around the Cape, but also in the landing area. A weather briefing had been held at 2:30 a. m. that morning, and the forecast was positive. Space agency officials noted patches of cloud high above the Cape, but were optimistic the weather would stay good enough to permit the launch.

Everyone who had spoken with Grissom that morning said he, too, was optimistic about his chances and was in excellent spirits. This time, however, there seemed to be a little added urgency attached to the pre-flight launch preparations; it was almost as if the scientists and technicians were unsure if their luck would hold along with the weather.

Grissom was awakened by Bill Douglas at 1:05 a. m. after a little less than four hours of sleep and given the good news that the weather looked good for a launch. Twenty minutes later he sat down with Douglas and Scott Carpenter for breakfast. There was no delay with the meal this time, which was a virtual duplicate of the one he had on Wednesday prior to being driven to the launch pad for the flight that never was.

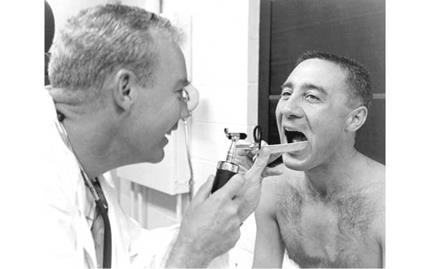

This time, as Grissom later noted, the buildup to launch time was proceeding well. At 1:55 Bill Douglas began a last full-scale physical to ensure the astronaut had not contracted any last-minute difficulties making him unfit for what would be an often grueling experience. There was another brief session with psychiatrist George

Ruff, who found there was no alarming level of anxiety in the astronaut. In fact, for Grissom this was almost part of yet another routine procedure that he had endured many times throughout his training and flight preparation. Ruff easily passed Grissom as mentally fit and ready to go. The biomedical sensors which would monitor the astronaut’s heartbeat, respiration and body temperature during the brief flight were attached at 2:25.

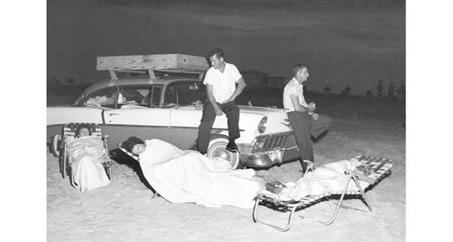

|

Everywhere along the beaches, people were camped out hoping to witness the historic launch. (Photo: NASA) |

|

Dr. Douglas gives Grissom a final medical check. (Photo: NASA) |

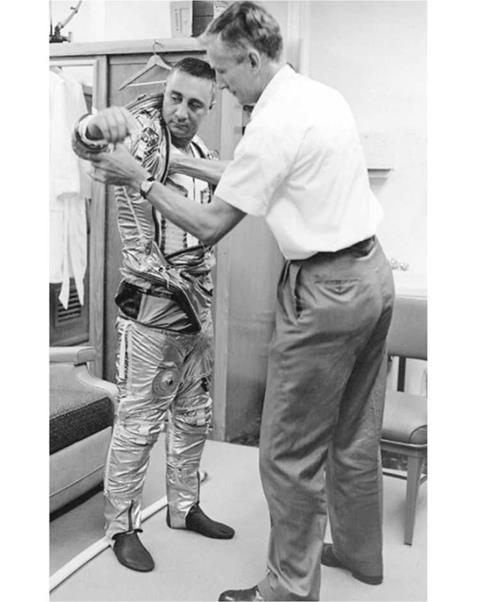

|

Suit technician Joe Schmitt assists Grissom in donning his space suit. (Photo: NASA) |

By 2:55, with the able assistance of Joe Schmitt, Grissom had worked his way into the close-fitting, rubberized and silver-coated space suit. Within ten minutes the suit had been inflated and checked for any possible leaks. No problems were encountered.

|

Grissom sits quietly as Schmitt adjusts a glove for him. (Photo: NASA) |

|

Bill Douglas and Wally Schirra check the suit pressurization for Joe Schmitt. (Photo: NASA) |

This time, Deke Slayton visited Grissom at his Hangar S quarters to brief him on the weather, the state of the rocket, and the preparedness of the capsule. Normally this briefing would have been carried out en route to the launch pad, but everyone was upbeat about the launch going on time. Grissom then hefted his portable air conditioner, which was known as the “Black Box” and, followed by Bill Douglas, made his way down the stairs to the exit door on the ground floor. Although his mouth was covered by the lower part of his helmet, he could be seen smiling through the open face plate at an assembly of about 60 space agency and air force personnel, photographers, and other spectators. He twice waved his left hand to acknowledge greetings. One NASA official called out, “Good luck,” and Grissom responded with an airy “Hi.”

|

Gus Grissom exits Hangar S accompanied by Dr. Douglas. (Photo: NASA) |

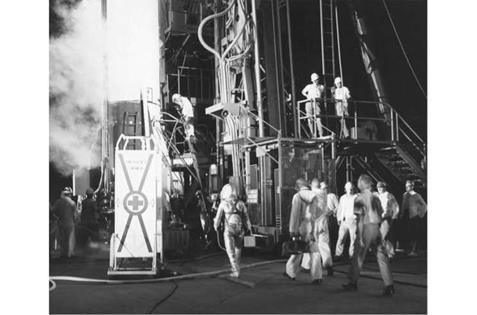

Riding in the transfer van at a sedate 15 miles an hour, Grissom reached the pad, three miles away, at 3:51 a. m. Two days earlier he had spent nearly an hour inside the van undergoing final briefings, but this time the door swung open in only a few minutes and Grissom, still clutching his air conditioner, cautiously descended the four steps and made his way to the gantry elevator several strides away.

Apart from a quick glance up at the towering Redstone rocket, Grissom looked straight ahead as he walked to the elevator in the peculiar bow-legged gait caused by the tight fit of his suit. This time there was no patter of applause from the helmeted

|

Holding his portable air-conditioning unit, Grissom makes a cautious exit from the transfer van. (Photo: NASA) |

|

While observing activity around the Redstone rocket, Grissom makes his way to the gantry elevator that will carry him to the spacecraft level. (Photo: NASA) |

workers on the pad. It was almost as if everyone was holding back their enthusiasm this time until the rocket actually lifted off. Before entering the elevator, however, Grissom exchanged a few light-hearted remarks with some of the men clustered near the elevator cage. Then, with everyone aboard, the elevator rose swiftly up the side of the red steel launch tower. It was a tight squeeze, with the space-suited Grissom, Douglas and other observers making the trip up to the capsule level 65 feet above the ground. The sky above them was dark, but a few stars were evident. Below, the pad area was bathed in dazzling white light from three banks of searchlights, all of them firmly aimed at the rocket.