MERCURY CAPSULE TAKES SHAPE

“We are building and designing the capsules at the same time,” Edward (‘Bud’) Flesh commented at the time. Flesh was the McDonnell engineer in charge of the project. “The design is not complete until we turn out a capsule, and each capsule will be slightly different from the one before, depending on whether it will be a test model or will carry an animal or an astronaut.”21

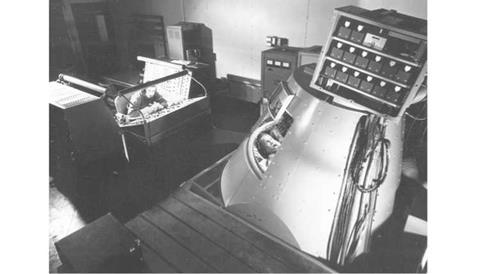

The capsules were assembled in rooms that could have rivaled hospital wards for cleanliness. Technicians and engineers wore white clothing made of dust-free nylon, and shoes of white nylon. The rooms, also white, were air-filtered and temperature-controlled.

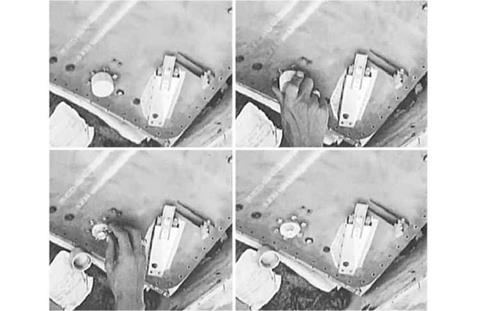

|

McDonnell technicians working on a Mercury capsule, 1960. (Photo: NASA) |

Psychologists, physiologists and engineers were all taking part in the design process, according to Fred Willis, one of the project engineers. “It would be silly, for example, to put a red warning light more than 50 degrees to the left or right of the man’s line of sight. Only the cones of our eyes see color, and the cones are not there for peripheral vision. A red light at the edge of our vision would not be recognized instantly as a danger signal. Maybe it seems a small point, but attention to detail like this makes the space ship as safe as a living room.”

One sticking point in the development of the first Mercury capsules was the subject of fitting viewing windows. Bud Flesh said it was a design problem that they had overcome. “As pilots, the astronauts are used to having a windshield,” he pointed out, “and even though it is probably more a psychological than a physical matter, we of course gave it to them.”22

Max Faget agreed on the subject of a viewing window – it was one of the design changes that had been unanimously demanded by the astronauts. “Oh, there was a big beef about that,” Faget told interviewer Jim Slade. “We had two little portholes about that big around; six-inch round quartz windows, one down here and one over here, and it wasn’t very good. And another thing we had is, in order to navigate, we had essentially – it was like a periscope, only actually it was optics to show them a virtual image here of the ground passing underneath them. We thought that was very important, that they see the ground so they could line it up with a reticule in there to make sure the vehicle wasn’t yawed. If they could see a piece of ground going right down along the center line, well they knew that they were headed right so when they fired the retro[rocket] off, they would be properly aligned. Actually, the [attitude] could be misaligned some fifteen or twenty degrees and it wouldn’t make that much difference. It would move the landing point further down range, but that’s about all. We had more than enough capacity [to retrieve the capsule]”.23

|

Astronaut John Glenn shows his wife Annie a replica of the Mercury spacecraft. (Photo: NASA) |

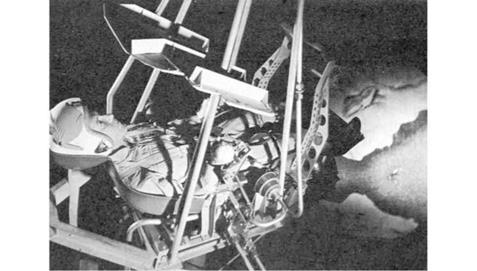

|

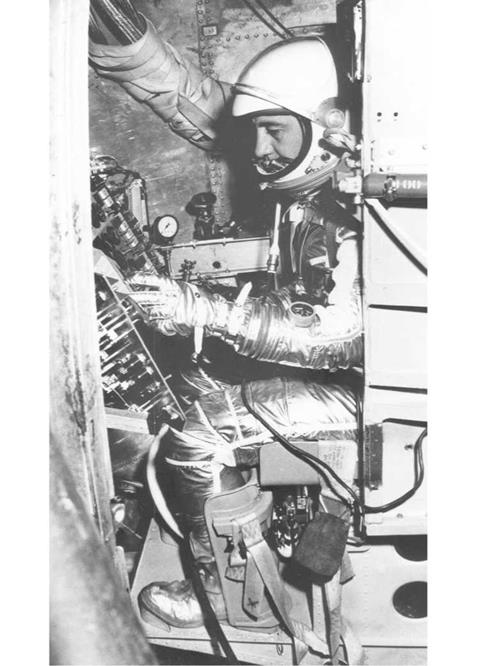

The U. S. Navy human centrifuge at Johnsville, Pennsylvania. The radius of the arm is 50 feet and the gimbal at the end of the arm changes positions as the centrifuge arm turns, by computer or by manual pilot control in the gondola at the end of the arm. The gondola and astronaut may be pressurized or depressurized for altitude as the accelerations are provided. (Photo: U. S. Navy) |

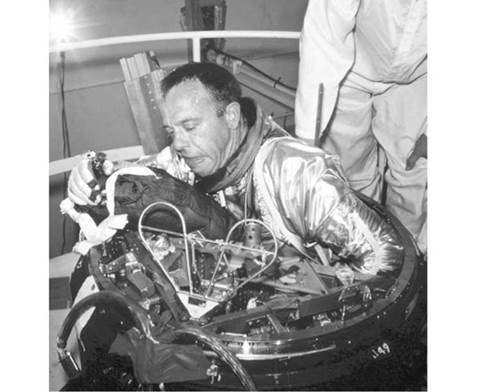

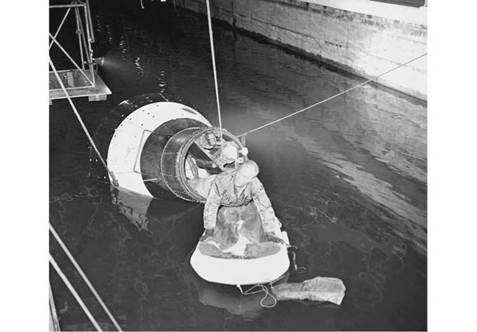

All seven astronauts visited the McDonnell plant in May 1959, where each man was assigned an appropriate systems engineer to provide individual presentations on the status of the different systems – their own particular part in them – and acquaint them with the people at McDonnell and the plant’s layout. After that they visited the Cape Canaveral launch site and trained at a number of military and medical facilities in accordance with the training program prepared for them by the STG. That August, for example, they were involved in human centrifuge tests at the Naval Air Development Center in Johnsville, Pennsylvania, learning to cope with excessive g-forces and the accelerations associated with their flights into space and back. They were unanimous that the centrifuge, which they referred to as “The Wheel,” was the hardest part of their training to that time.

As Alan Shepard explained, “This thing – the centrifuge – puts you in what pilots call the ‘eyeballs-out’ position. It is like an oversize cream separator that flings you around the room, that sort of thing. If you fight it, it’s murder. You can easily black out and remain unconscious. When I come off that monster at Johnsville, every bone in my body aches.”

Scott Carpenter agreed with Shepard. “It’s important to master these g-forces because we fully expect to be operating the capsule controls during part of the flight. So far, we have all shown this capability under 9 Gs. But that’s assuming everything goes according to plan. If it doesn’t… well, let’s not talk about that.”

“Just say it is a real personal challenge,” added Shepard.24

In September the Mercury astronauts returned to the McDonnell plant to check on progress with the spacecraft that they hoped they would soon fly. As Luge Luetjen recalls, “During this and subsequent visits, we developed lasting first-name friendships and a mutual respect for each other’s role in the ‘great adventure.’ Their suggestions and recommendations throughout the program were timely, well thought out, and were of great help in the design, construction, and testing of the machine.”25

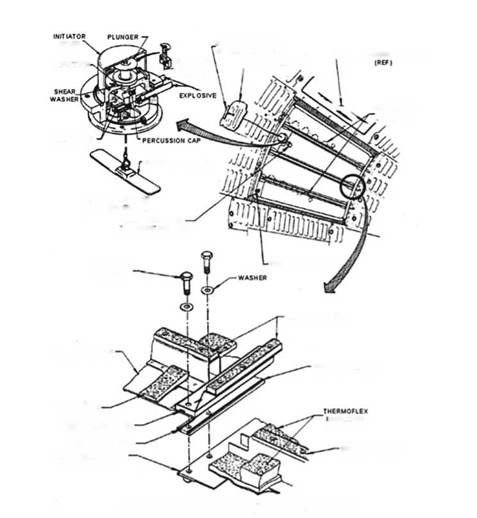

EXPLOSIVE CHARGE

EXPLOSIVE CHARGE