PREPARING FOR A PICKUP

At 7:36 a. m., just 15 minutes 37 seconds after lifting off from Cape Canaveral, America’s second manned space flight came to an abrupt end as Liberty Bell 7 plunged into the Atlantic at 28 feet per second. Gus Grissom recalls being a little surprised that the only sensation he felt on splashdown was a mild jolt, which he later equated to impact with the ground after a parachute jump, and “not hard enough to cause discomfort or disorientation.”5

As expected, the spacecraft heeled over in the choppy seas, and moments later the window was completely underwater. For a few seconds Grissom imagined he was upside-down, but the spacecraft soon began to right itself in the water. He did hear what he later described as a “disconcerting gurgling noise” as Liberty Bell 7 slowly rolled upright and the recovery section on top of the capsule drew clear of the water. A quick check reassured him that no seawater was entering the spacecraft. His next action was to jettison the reserve parachute by clicking a recovery aids switch. He heard the chute jettison and through his periscope could see the canister drifting away in the choppy water. He reported that he was in good shape whilst switching on a radio beacon and other rescue aids and deploying a sea marker which spread a bright green dye. He then began to complete his final checks, as he later reported in his post-flight debriefing.

“I felt that I was in good condition at this point and started to prepare myself for egress. I had previously opened the faceplate and had disconnected the visor seal while descending on the main parachute. The next moves, in order, were to disconnect the oxygen outlet hose at the helmet, unfasten the helmet from the suit, release the chest strap, release the lap belt and shoulder harness, release the knee straps, disconnect the biomedical sensors, and roll up the neck dam. The neck dam is a rubber diaphragm that is fastened on the exterior of the suit, below the helmet-attaching ring. After the helmet is disconnected, the neck dam is rolled around the ring and up around the neck, similar to a turtleneck sweater. This left me connected to the spacecraft at two points – the oxygen inlet hose which I needed for cooling, and the helmet communications lead.”6

Next, Grissom radioed the waiting helicopter pilot Jim Lewis. “Okay, Hunt Club, give me how much longer it’ll be before you get here.”

“This is Hunt Club,” Lewis responded. “We are in orbit now at this time around the capsule.”

“Roger,” Grissom radioed back. “Give me about another five minutes to [record] these switch positions here, before I give you a call to come in and hook on. Are you ready to come in and hook on any time?”

Aboard Hunt Club 1 Lewis was prepared for the operation. “Roger. We’re ready any time you are.”

“Okay; give me about another three or four minutes here to take these switch positions, then I’ll be ready for you.”7

According to plan, Grissom then noted down all the switch positions using a grease pencil. “All switches were left just the way they were at impact, with the exception of the rescue aids, and I recorded these by marking them down on the switch chart… and then put it back in the map case.”8

|

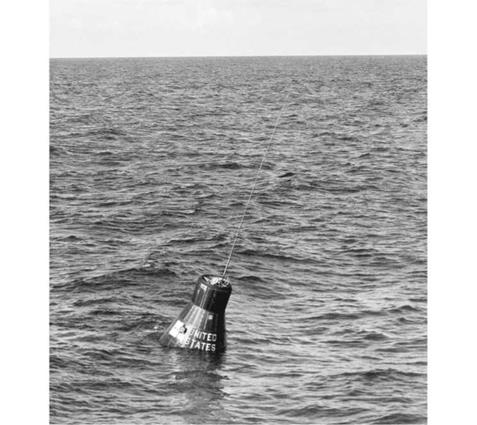

Liberty Bell 7 after splashdown, showing the HF whip antenna fully extended. It had to be cut by the prime helicopter crew prior to attempting to descend and hook onto the spacecraft’s recovery loop. (Photo: NASA) |

Recording the positions with a grease pen while wearing pressure suit gloves proved difficult, but he completed the task. The suit ventilation was continually causing his neck dam to swell, which he alleviated from time to time by jamming a gloved finger between his neck and the dam to allow a buildup of air to escape.

Once his shut-down duties and checks had been completed, Grissom turned his attention to oft-rehearsed preparations to blow the hatch. “I took the pins off both the top and bottom of the hatch to make sure the wires wouldn’t be in the way, and then took the cover off the detonator and put it down toward my feet.” He had earlier removed the hand-forged Randall survival knife from its sheath in the door and placed it in his survival pack as he called in the rescue helicopters. He admits that a short while later, as he lay back in his couch waiting for the helicopter to arrive overhead, he contemplated retrieving the knife from his survival pack and keeping it as a souvenir of the flight. Specially made for NASA, only nine were produced: one for each of the astronauts, and two spares. They were one of the strongest knives ever made, fashioned from high-grade Swedish steel, which Gordon Cooper once described as “so sturdy that it can be used like a chisel to cut through steel bolts. You could probably slice your way right through the capsule wall with it if you had to.”9

Grissom was satisfied that he had completed all of his pre-egress tasks. Once the prime helicopter had hooked up to Liberty Bell 7 and raised the hatch clear of the water the pilot would confirm that all was in readiness. All Grissom had to do then was punch the detonator plunger with a five-pound blow and the hatch would explode outwards from the spacecraft, allowing him to slide out onto the door sill and wait for the rescue sling to be lowered. It was then just a matter of being winched up into the helicopter. Following this, he and the capsule would be transported together to the waiting carrier, emulating the successful retrieval of Alan Shepard and Freedom 7 some ten weeks earlier.

Meanwhile, Jim Lewis had responded to Grissom’s transmission, advising the astronaut that the rescue sling would be ready for him outside the capsule once the hatch was explosively jettisoned. Each of the Marine rescue helicopters carried a two – man crew; on Hunt Club 1 Lewis and his co-pilot Lt. John Reinhard were working well together as a team. Despite the noise within his cockpit, Lewis later reported communications with the spacecraft were “normal and excellent, as the system was designed for that acoustic environment, so all was nominal. All our voices were calm. We’d rehearsed these procedures and activities [in Chesapeake Bay] off Langley AFB with the astronauts, and there was no reason not to be calm. That’s what good training does. In addition, Gus had a low resonant voice, which was pleasant to hear. It was all very calm and professional. There were Navy aircraft in the area available to provide communication relays in case they were needed and to extend the search area if needed. As I recall, there were Russian trawlers in the general area, but not the actual recovery zone.”10