DEVELOPMENT OF THE CAPSULE

The contract signed with McDonnell Aircraft was a cost-plus-fee type, with a cost figure of $18.3 million dollars and a fee of $1.15 million dollars. As Luge Luetjen indicated, the contract “set in motion what was to eventually become one of the largest

technical mobilizations in American history involving some 4,000 suppliers, nearly 600 direct contractors from 25 states, and over 1,500 second tier subcontractors. To manage such an effort, Mr. Mac and Dave Lewis (by then second in command) named Logan MacMillan, a former chief test pilot and head of flight test, as the Mercury Company-wide Program Manager. Under Logan was E. M. (‘Bud’) Flesh as Engineering Manager, Bill DuBusker as Manufacturing Manager and, of course, [John] Yardley as Project Engineer. After a short time, NASA felt there should be someone at vice presidential level in charge, so Mr. Mac designated Walter Burke, already a vice president in charge of the entire factory, as the Vice President and General Manager of the Mercury program.”13

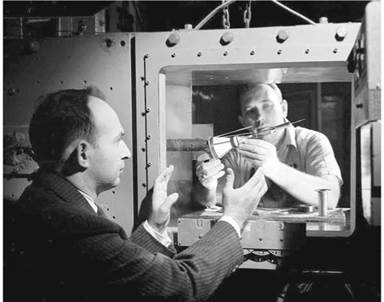

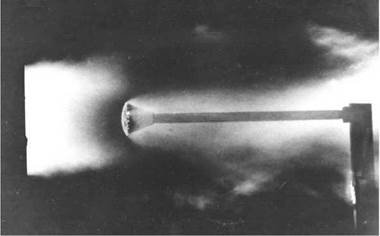

Beginning in February 1959, endless tests of different small-scale spacecraft shapes began in wind tunnels across the United States. Engineers, technicians and designers then studied the resulting flow effect in photographs, looking closely at phenomena such as shock waves, wind streams, and vortices. By the end of the year some 70 design models had been tested and analyzed, with results proving a full-scale capsule could handle the tremendous aerodynamic stresses associated with launch and reentry. As well, they established that the blunt shape at the bottom of the capsule would provide sufficient drag to slow the craft down during its descent through the atmosphere. In tests, NASA engineers applied 6,000-degree jet flames onto that same blunt end to demonstrate its ability to withstand the incredibly high temperatures associated with reentry.

|

Testing a small-scale model of the Mercury capsule/escape tower assembly in an 18 inch by 18 inch wind tunnel. (Photo: NASA/Langley Research Center) |

|

|

Scientists at the Langley Research Center operated hot jets, quartz-lamp heat radiators, furnaces and other specialized research facilities in making tests at temperatures up to 10,000°F on space vehicle structures and materials. This scale model, made of fiberglass and plastic, was exposed to a 5,000°F arc-heated air jet. (Photo: NASA/Langley Research Center)

|

|

A Mercury capsule prototype undergoes testing in the Full Scale Wind Tunnel at Langley Research Center in January 1959. (Photo: NASA/Langley Research Center)

Once all the preliminary design work was complete, McDonnell manufactured several scale models of their own for testing purposes. As Max Faget, Caldwell Johnson and others were no longer needed in the design development of the capsule, the MAC team also went to work on testing full-scale, non-functional “boilerplate” models.

|

The McDonnell Mercury Design Team (circa 1959). From left: Jack Crouch, Chuck Jahn, Earl Younger, Norris LaGrant, Bob Roth, John Dale, ‘Bud’ Flesh, John Yardley, Bill Mosley, George Weber, Harry Condit and ‘Luge’ Luetjen. (Photo: McDonnell Aircraft Corporation) |

To bridge the gap between the signing of contracts to construct the spacecraft and their actual delivery, and to aid in astronaut training, the Langley Research Center employed full-size replica Mercury capsules constructed from steel plates. These became known as “boilerplate” mockups. Test launches of boilerplate models were carried out using Sergeant and Recruit rockets, while others were conducted at Cape Canaveral using Redstone, Atlas and Scout boosters.