SOME PERSONAL REFLECTIONS

An air of mystique quickly surrounded the Mercury astronauts. People eagerly sought out and consumed information about them and their families in newspapers, especially through Life magazine, which was awarded sole rights to their stories under a mutually beneficial deal thrashed out between the astronauts’ tax attorney Leo D’Orsey and the magazine.

Perhaps the most enigmatic of the seven was Gus Grissom, who tried to avoid the press and public speaking whenever he could, although he abided this as part of his duties as a NASA astronaut. He was more at home in the cockpit of a fighter jet or poking around inside a space capsule than he was in revealing details of his private life. A man of few words, he was quickly given the rather unfair sobriquet of “Gruff Gus.” He didn’t care; he had a job to do, and he disliked distractions.

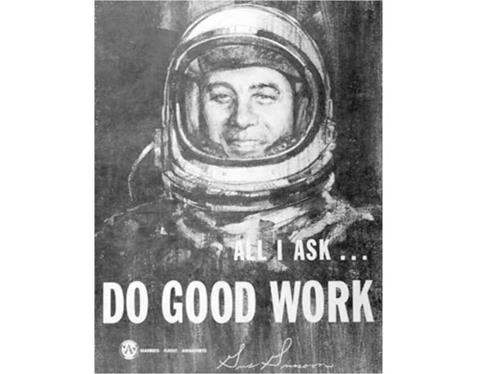

One of the lesser-liked duties for most of the Mercury astronauts – particularly Grissom – involved giving speeches. But on one occasion he unwittingly created a humorous, oft-repeated story that would always follow him around. It came about when all seven astronauts were on a tour of the Convair plant in San Diego to see Atlas rockets under construction. At one stage of their visit the astronauts were seated on a podium outside the plant, in front of 18,000 cheering employees. A Convair executive made a short speech, then turned and asked if an astronaut would care to respond. Grissom somehow found himself propelled forward to the microphone by his fellow astronauts, but he had been caught off-guard and was unprepared. As the tumultuous applause died down he cleared his throat and suddenly developed a dose of stage fright. He hesitated, raised his hands for quiet and blurted out, “Well.. .do good work!” He then rejoined the other grinning astronauts. Momentarily, the crowd was silent, and then they burst into wild clapping and cheering. It was as if he’d just recited the Gettysburg address, and the workers loved him. “Do good work!” – it now became their mantra and mission statement. Gus’s stammering slogan was stitched onto a huge banner, which was hung above the plant’s work bay to serve as an inspiration to all.

Another side of Gus Grissom was recalled by Frank Moncrief from Virginia Beach, Virginia, who shared a particularly vivid memory of the astronaut during a training session.

|

A poster inspired by Gus Grissom’s three words to the Convair employees. (Photo: NASA) |

“The original seven astronauts were sent to Little Creek Naval Amphibious Base so the Navy frogmen could give them scuba lessons. It was believed that weightlessness in water was similar to weightlessness in space. I was honored to be one of the frogmen picked to be an instructor.

“These guys were the sharpest of the sharp. John Glenn asked me how the AquaLung valve worked, and I explained in detail the valve’s functions. That did not satisfy him. I had to take the valve apart, explaining every screw, every spring and every diaphragm. They were that thorough. For graduation, the astronauts entered the pool with a full tank of air and were told to swim around without coming up for anything. We instructors began harassing them, pulling off a face mask or fins, pulling out mouthpieces, turning off their air. Then we brought them to the surface and congratulated them. I was proud to have been a part of that. But it wasn’t over.

“A couple of weeks later, we got word that the astronauts were inviting the instructors to ride in a jet. When we arrived at Langley, the astronauts greeted us like old buddies. I was given Deke Slayton’s helmet and Walter Schirra’s flight suit to wear. My pilot was Gus Grissom, and we boarded a T-33 jet trainer. He told me to put my left hand on my left knee and my right hand on my right knee and not to touch anything. I did as I was told.

“Gus started to describe everything: ‘I am going to start my rollout; when the aircraft gets to 180 knots I will lift this tub off the ground.’ (These guys were used to flying high – performance aircraft, so flying a T-33 was demeaning.) He threw the plane into a steep left-hand bank – WOW! The g’s! My helmet felt like it weighed a ton. Then Gus straightened out the plane and said there was a hole in the clouds. WOW, again! We went from 3,000 to 10,000 feet in seconds. The clouds looked like lava-lamp spirals. Gus began to fly around these spirals, up and down. He asked me how I was doing, then said, ‘Frank, don’t you dare throw up in my plane.’ I answered, ‘Gus, just before I die, I am going to throw up in this plane.’ (I was close.) Then we leveled off, to my relief.

“Gus said, ‘There’s Richmond down there.’ I said, ‘How can you tell from up here?’ He said, ‘Let’s go take a look.’ We went straight down. WOW – more g’s and g’s. Then, thank God, he leveled off again.

“When we landed back at Langley, we got out of the plane, and Gus put an arm across my shoulders, pointed up and said, ‘Frank, that’s my pool.’

“I answered: ‘Touche, Gus.’”10

All of the Mercury astronauts were highly competitive individuals, even amongst themselves. The late Cece Bibby was an exceptionally gifted artist who found fame as the person who painted insignias on the sides of the orbital Mercury spacecraft, and she recalled that “each of them wanted to have the first flight. It didn’t matter that the first couple of flights would be suborbital; first was first and that was part of the attraction.

“These guys had really fought to be named the first astronauts, although some people referred to them as astronaut candidates. Wally Schirra once said that they were actually only ‘half-astronauts’ until a space flight was made. So, after the first seven were picked they then fought to make the first flight. This led to a lot of good-natured competition and jockeying for position and it involved every aspect of their flights.

“When Al made his flight there was a stencil cut for the name Freedom 7 and the name was sprayed onto the capsule. The same was true for Gus’s Liberty Bell 7. I don’t know who sprayed the names on the capsules. I do know that when John Glenn decided he wanted his Friendship 7 hand painted on his capsule there was a good bit of ‘joshing’ that went on about it. Al and Gus made comments that a stencil wasn’t good enough for John; that he had to have his name hand painted by an artist.

“Gus told me later that he wished he’d have had an artist do his Liberty Bell. He said it really bugged him that someone else thought of it and he hadn’t. Competitiveness.”11

That same competitiveness also involved fast cars and the pulling of pranks – or “gotchas” – on each other. Grissom’s brother Lowell recalled one hilarious incident.

“It was late evening, and [as] Gus exited the Cape’s gates, he drove his Corvette at its usual speed of 100 miles per hour. He got on the first highway, and one cop picked him up and started chasing him. A little further away, a second police car joined the chase. And by the time Gus reached Cocoa Beach, three police cars were following him.

“Gus was far ahead of them, and when he reached the motel where he was staying he parked his Corvette in front of Alan Shepard’s room, then walked into his own. The cops came and saw the Corvette sitting there and felt the hood and said, ‘Yeah, this is it.’ And they banged on Shepard’s door. Shepard comes to the door, half-asleep, and they pull him out, throw him on the ground and cuff him. Meanwhile, Gus had changed into pajamas and was watching from his room.

|

Cece Bibby painting the Friendship 7 logo onto the side of John Glenn’s spacecraft. (Photo: NASA) |

“As the police officers handcuffed Shepard, Gus yelled at them out the window. ‘Hey, guys, can you hold it down out there? Some of us have to go to work in the morning!’”12

Whatever his faults, or the perception others might have of him, no one could deny the application, thoroughness, and expertise that Gus Grissom brought to his work and training. He gained everyone’s respect, and two years after the selection of the Mercury astronauts his dedication to the task was rewarded by the assignment to his first flight into space.