Salyut 7 and Spacelab

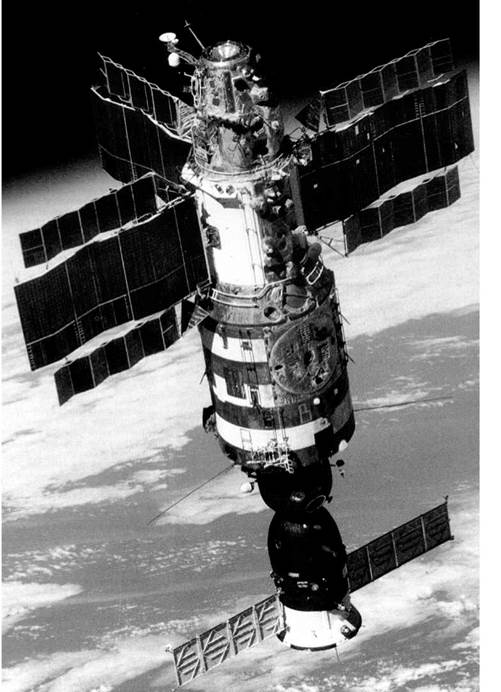

Salyut 6 had been an impressive step forward in space station technology and operations. Salyut 7 was the back-up to Salyut 6 and, therefore, similar in design, but it did have improved systems, and extra comforts for the crews that were likely to be aboard for much longer periods than previously. Personal selection of food items was allowed for the first time, and there was a small refrigerator for the fresh food delivered by Progress. Extra storage was provided, but it would prove to be still not enough as the life of the station lengthened.

Launched on 19 April 1982, Salyut 7 was to have a long life and more resident crews than Salyut 6. The introduction of the updated Soyuz-T spacecraft would allow more flexibility in crew visits owing to its ability to spend more time in space. It was also hoped to achieve the first operational rotation of crews, with a new crew arriving and having the station handed over to them before the old resident crew left. This would save considerable time and resources, as it meant that the station would not have to be powered down and up again by subsequent crews.

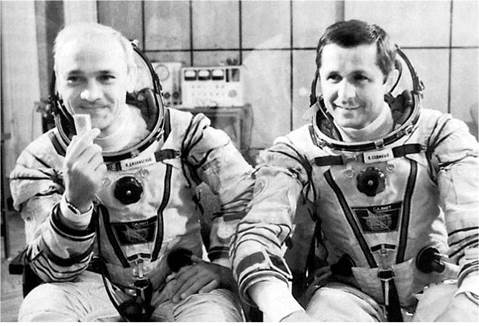

Soyuz-T 5 was launched on 13 May 1982 with the first resident crew of Valentin Lebedev and Anatoli Berezovoi—this was defined as the EO-1 crew. They were initially given light duties for their first few days in orbit as they worked their way through the tasks required to commission the new station. New experiments were set up, and the crew slowly settled into a daily routine as they awaited their first visitors. Soyuz-T 6 was launched just over a month later, and carried the first crewmember from outside the Inter-Kosmos organization, Frenchman Jean-Loup Chretien, who was to carry out a series of medical experiments. As did short-term visitors, he wore himself out, shortening his sleep periods to maximize his time in orbit, and by the time Soyuz-T 6 undocked from Salyut 7 to return to Earth, he was exhausted. However, the resident crew of Lebedev and Berezovoi were just as tired, because hosting visitors was hard work, as previous crews had found, and ground controllers gave them a few days off to allow them time to recover. In addition, the two men did not really get on that well; they had not bonded during training for the mission, but for some reason

|

Soyuz-T 5 crew |

they had not been reassigned to separate missions. Two men aboard a small space station is never going to be an easy period of time to get through, particularly when it is for such a long period of time, but this pair seemed to exploit every excuse for arguing with one another, even over trivial things. The only break for the crew came

|

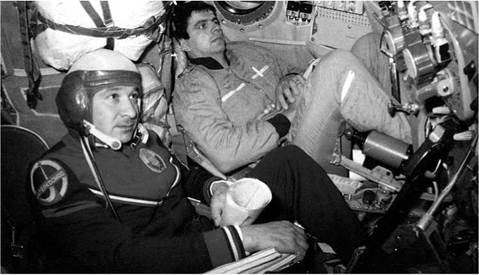

Soyuz-T 7 crew |

when visitors arrived, and the next set of visitors would be more welcome than most, because it included a woman.

Soyuz-T 7 established another space triumph of sorts for the Soviets. Svetlana Savitskaya was the second woman in space after Valentina Tereshkova in 1963. It was obviously no coincidence that NASA had announced earlier in 1982 that Sally Ride would fly on board the space shuttle’s seventh mission. The Soviets wished to trump NASA’s latest public relations scoop, and assigned Savitskaya to the flight at relatively short notice. However, it is unlikely that the more liberal American Sally Ride would have accepted the flowers and floral apron that were presented to Savitskaya by her male colleagues. Her flight was relatively short, lasting only seven days before the visitors returned to Earth in the older Soyuz-T 5, leaving Soyuz-T 7 for the long-duration crew.

Alone again, the two men struggled to get along; there was a momentary panic when Berezovoi felt unwell one day during an exercise period. His illness threatened the length of the mission, and both men felt angry that having put up with each other for all this time, they might have to come home early. Ground controllers recommended that Berezovoi be given an injection of atropine to ease the pain, and this helped, causing him to feel much better by the next day; the mission could continue. Finally the crew had reached their personal limits, and they were allowed to return home. They had set a new endurance record of 211 days, but their landing and recovery did not go completely smoothly, as they had to spend the night on board a disabled, and cold, helicopter. This was the last straw for the two men, and in the twenty odd years since their joint flight, they have barely spoken to each other.

The launch of Soyuz-T 8 on the 20 April 1983 did not go entirely to plan. The crew of Aleksandr Serebrov, Gennady Strekalov, and Vladimir Titov were unable to dock with Salyut 7 because one of the spacecraft’s rendezvous antennas was damaged at launch; they returned to Earth on the 22 April. Soyuz-T 9 docked with the station on the 28 June carrying Vladimir Lyakhov and Aleksandr Aleksandrov. As the next long-duration crew, EO-2, they were due to receive visitors, but unfortunately the launch of Soyuz-T 10-A, again crewed by Strekalov and Titov, was aborted and the launch escape system used when the booster caught fire during the last moments of the countdown. Thus, Strekalov and Titov failed for the second time that year to get to Salyut 7, where they were supposed to add solar arrays to the station. This task would now fall to the resident crew. Following on from the success of Cosmos 1267 with Salyut 6, Cosmos 1443 had docked with the station prior to the arrival of the Soyuz-T 9 crew, and was loaded with 3.5 tonnes of supplies. During its stay, Cosmos 1443 was used to provide attitude control for the station, and to boost Salyut 7’s orbit. The re-entry module would later turn up at a Southerby’s auction in 1993. The crew set about unloading just after they arrived; they then loaded the TKS’ re-entry module with experiment results, which returned to Earth in August. They carried out the spacewalks to install the solar panels (which were cargo in the large module) just a few weeks before their return to Earth on 23 November, after 150 days in space, having received no visitors. At around this time it was noticed by the resident crew, and ground controllers, that Salyut 7 was leaking fuel from its propellant tanks, severely limiting the station’s maneuvrability. Plans were made for the next crew to attempt to fix the problem, rather than abandon Salyut 7 at this early stage.