1973-1974: Salyut 2 and Salyut 3—limited success

Salyut 1 had not been a failure; the death of the returning crew was tragic, but the space station itself had been blameless. The Soviet space organization was keen to launch another as soon as possible. Of course they had to wait until the Soyuz ferry vehicle was ready to resume flight. Arguments raged over the best way to achieve a safer Soyuz design, Chief Designer Vasily Mishin argued that simply adding space – suits to the capsule was not the right answer, it limited the crew to two and seriously reduced the cargo the ferry could carry to and from orbit in addition to the crew. However, he was overruled by the Secretary of the Central Committee, Dmitri Ustinov, who was absolutely determined that no cosmonaut would be launched into orbit without a spacesuit ever again. Mishin continued to argue that reliability of the systems was the best method of ensuring the safety of the crew, but he was told in no uncertain terms that Ustinov’s word was final, and that pressure suits were to be installed. This required a new version of the Soyuz spacecraft that would only have an orbital lifetime of two days. This was necessary as the solar arrays of the previous version had to be removed to save weight, and the on-board batteries would only last for that limited time.

After the “civilian’’ first station, it had been decided to introduce the first pure Almaz design, designated OPS-1, albeit using the Soyuz craft as the ferry instead of the TKS. The Almaz design also differed from the first Salyut in that its docking port was at the rear of the station. OPS-1 made it to Baikonur in the midst of the harsh winter of January 1973, and during the next 90 days military testers and civilian specialists prepared it for launch. The OPS-1 blasted off into orbit on 3 April 1973. Since the authorities did not want to disclose the existence of two space station projects in the USSR, and particularly, to reveal the development of the military Almaz, the OPS-1 was announced as Salyut 2 upon reaching orbit. It was given the Salyut name to disguise its military configuration, but it was different to the space station that had preceded it. It was several meters shorter, but weighed about a ton and a half more. In the center of its living compartment a huge camera was installed

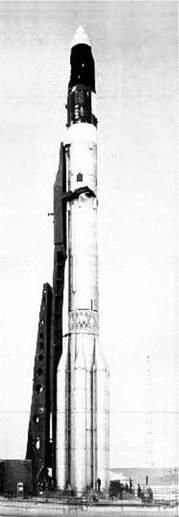

|

Proton launcher with Salyut 2 |

in the “floor” and the station had a much higher level of automation to reflect the reduction in the Soyuz crew.

Unfortunately this new station did not last long enough for any crew to board it, and perhaps this was just as well, because 13 days after launch an electrical fire in the propulsion unit spread to the main compartment, explosively decompressing the station and sending it spinning out of control until it broke up. The official investigation concluded that as a result of a faulty welding, one of the lines in the station’s propulsion system had burst during an engine firing and the plume of flame had burned through a pressurized hull. However, future findings were to cast doubt on this theory. Careful analysis of fragments detected in orbit, showed that three days after the launch of the OPS-1 the upper stage of the Proton rocket that had delivered the station apparently exploded as a result of pressure changes in its tanks resulting from overheating. The stage carried about one tonne of unspent propellant, and the explosion created a cloud of debris in the proximity of the station. The speed of some debris differed from that of OPS-1 by as much as 300 ms_1. Eight days later, a piece of this orbital junk apparently hit the station. However, despite all this secrecy and the attempt to cover up the military nature of the station, western observers almost instantly managed to discern the military nature of the new spacecraft. An article appeared in the September 1973 issue of Aviation Week, which read, “Soviet penchant for secrecy within its own space program has lead to a widespread, but erroneous, belief that a Salyut spacecraft failed while in orbit. The spacecraft, which the Soviet press and information agencies called a Salyut, was launched Apr. 3 and apparently suffered a catastrophic failure on Apr. 14. However, the spacecraft transmitted on a different frequency than previous Salyuts and now is believed to have been a different spacecraft. The reports initially issued by the Soviets apparently were incorrect because of an attempt to keep secret the actual nature of the spacecraft. Telemetry transmissions from the spacecraft were similar to those monitored earlier from Soviet reconnaissance satellites.” Although the Almaz name was not known in the West for many more years, these stations had become identified in the West as “military Salyuts”.

Undeterred, the Soviets launched another station only a month later. This was not an Almaz, but the third station in the DOS series. DOS-3 carried several improvements over the earlier configuration. It had improved solar arrays in an effort to double the overall lifetime of the station from the 90 days of the two previous stations. In most other respects, however, the station was basically the same, although more thought had been given to automating systems to accommodate the reduced crew of two. Unfortunately, due to errors in its flight control system, and while out of the range of ground control, the station fired its orbit-correction engines until it ran its tanks dry, and a week later re-entered the Earth’s atmosphere. Since the station had reached orbit, and therefore been tracked by western ground stations, the Soviets had to acknowledge its existence but, in a effort not to give anything away, designated it Cosmos 557 as a form of disguise.

The Soviets finally enjoyed some success with the launch of Salyut 3, a station of the Almaz design, in June 1974. The OPS-2 space station really was a reconnaissance platform, for it housed a massive 6-meter camera in its main compartment and had a capsule for the high-resolution film to be returned to Earth independently of the crew. In all 14 cameras were to be used on board. The other notable feature of this station was the modified aircraft machine gun that was mounted near the front port for station defence! In order to point it at the target the crew had to change the attitude of the entire station.

When the Salyut 3 station was launched a small group of teachers and school children in Northamptonshire, England, were glued to their radio receivers. The group would later become known simply as the Kettering Group, but for now physics teacher Geoffrey Perry and some of the pupils from Kettering Grammar/Boys School

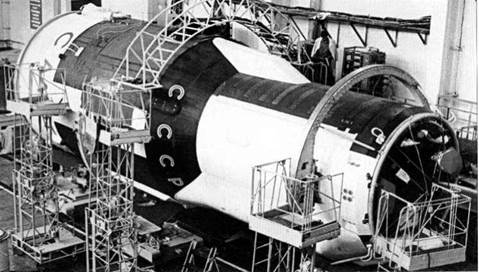

|

|

had no particular name. They had for some years been following the satellite launches from both the U. S.A. and the Soviet Union by means of radio receivers within the school. He and his team of teachers and pupils had amassed a great deal of knowledge, particularly about Soviet satellites, since the launch of Sputnik 2 in 1957. Mr. Perry correctly identified launches from a site other than Baikonur in 1966, which would be later known as Plesetsk, and was also the first to record evidence of the first unmanned Soyuz test after the tragedy of Soyuz 1. Now with the launch of Salyut 3, they hoped to positively identify the station for themselves. But when they listened to the same channels that they had listened to previously for manned Soyuz

|

Salyut 3 on the ground before launch |

|

Salyut 3 gun |

missions and the Salyut 1 station, they could hear nothing. The same thing had occurred the previous year with Salyut 2, and they wondered why this could be. It was later determined, with the help of other radio amateurs, that the station was using a frequency only usually used by military reconnaissance satellites. Although it was immediately apparent that this change of frequency meant that the station was military in nature, it was clear that it was being operated differently than the previous Salyut station. They hoped to confirm their hypothesis when the inevitable Soyuz spacecraft was launched to dock with the new station.

The crew of Soyuz 14 were Pavel Popovich and Yuri Artyukhin, both military officers, who were launched on 3 July 1974 and docked later that same day.

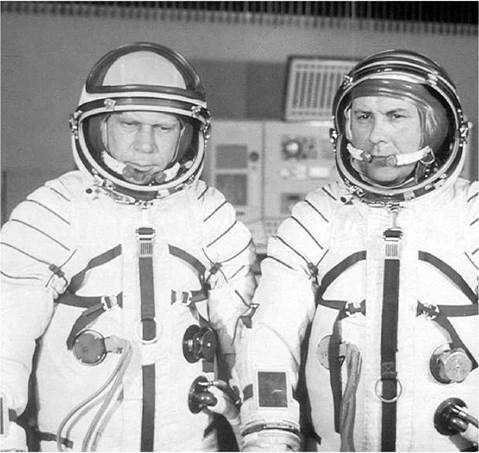

|

Crew of Soyuz 14 |

According to Popovich, the on-board automated rendezvous system delivered the Soyuz spacecraft only 600 m from the station and from a distance of 100 m the crew switched to manual control. Popovich remembers taking off his spacesuit gloves, (unpressurizing his suit, as a result) in order to make it easier to control the craft. The Kettering Group were able to identify for themselves that the Soyuz was only manned by two cosmonauts, and determined the identity of its commander, and they made a press announcement to the world through Reuters before the Soviet Union had even officially announced the launch. By comparison the U. S. CIA had no such detailed information; in a National Intelligence Estimate dated December 1973 they seemed only to be aware of the civilian Salyut program, and gave no indication that they had any information regarding the military Almaz program.

Popovich and Artyukhin entered the OPS-2, having docked at the rear, on 4 July 1974 and spent 15 days on board. According to official sources, the “remote-sensing

equipment” was activated on 9 July, followed by several days of photography of the “Earth surface”. Central Asia was among officially disclosed targets of the station’s cameras. Western sources also say a set of targets laid out near Tyuratam was photographed to test the capabilities of the surveillance hardware. Several times during the mission, an on-board alarm system woke up the crew; however, it proved to be false. During the flight, the cosmonauts reportedly checked the systems on board, adjusted the temperature inside the station, moved some ventilators and completed other housekeeping chores. They also reloaded the station’s on-board cameras and placed exposed film into the space station’s return-to-Earth capsule.

The second crew consisted of commander Genadi Sarafanov and flight engineer Lev Demin, and they were launched on board the Soyuz 15 spacecraft on 26 August 1974. However, problems with the rendezvous system on board the Soyuz during the approach to the station forced officials to cancel the docking attempt. The spacecraft returned to Earth after a two-day flight, the limit of the Soyuz’s orbital endurance, and was forced to land under night-time conditions. Typically for the period, official sources reported only that the Soyuz 15 crew “tested various rendezvous modes during its mission’’.

Two decades later, the official history of RKK Energia revealed that when Soyuz 15 reached a distance of 300 m from the station, the Igla (“Needle”) rendezvous system, failed to switch to the final-approach mode and instead started implementing a sequence that would normally be executed at a range of 3 km from the station. On commands from the Igla, the Soyuz fired its engines, accelerating itself in the direction of the station. The relative speed of Soyuz 15 to the OPS-2 reached 72kmh-1, zooming by the station at a distance of 40 m. As the crew failed to realize the problem (and to shut down the Igla), the rendezvous system attempted to reacquire radio-contact with the target and sent Soyuz 15 to the station twice more each time narrowly avoiding a collision. By the time ground control commanded the deactivation of the Igla, the crew only had enough propellant for the descent back to Earth.

Due to lengthy modifications in the wake of Soyuz 15’s rendezvous problems, no further expeditions to Salyut 3 could be staged. The return-to-Earth capsule was jettisoned from the OPS-2 on 23 September 1974 and successfully recovered on Earth, and the station was de-orbited on 24 January 1975 over the Pacific Ocean.

According to official Soviet sources, the seven-month flight of Salyut 3 exceeded more than twice the originally planned flight duration. Soviet publications also disclosed that Salyut 3 was the first space station to maintain constant orientation relative to the Earth’s surface. To achieve that, as many as 500,000 firings of the attitude control thrusters had been performed. This fact also hinted to Western observers that Salyut 3 had perhaps carried out a reconnaissance mission.

Years later it was revealed that shortly before de-orbiting OPS-2, ground controllers commanded the “self-defence” gun on board the station to fire. According to Igor Afanasiev, an expert on the history of space technology, firings were conducted in the direction opposite to the station’s velocity vector, in order to shorten the “orbital life’’ of the cannon’s shells. A total of three firings were conducted.