1970-1979: Skylab—NASA dips its toe

In March 1970, the Skylab project received official approval by President Nixon when he referred to it during a speech about America’s goals in space for the coming decade and beyond. However, this was a difficult time for NASA, they had achieved President Kennedy’s challenge of landing a man on the moon before 1970, indeed they had done it twice with Apollo 11 and 12, and now they faced the inevitable postsuccess anticlimax, and the people of the United States lost interest. The Soviet threat to the moon landings had failed to materialize, and the risks of further moon landings were all too clearly demonstrated during the flight of Apollo 13 in April 1970. NASA’s budget had been slowly reducing for years now, and finally they had to cut flights: two Apollo missions were deleted from the program that would now end with Apollo 17 in 1972. It was at this time that the first hint of co-operation with the Soviets became apparent, with a suggested docking of a Soyuz with the Skylab workshop. This was at a time, of course, when the Soviet’s plans for their Salyut stations was completely unknown to the Americans until Salyut 1’s launch in 1971. NASA then suggested that perhaps an Apollo CSM could dock with a Salyut station, but the Soviets were not keen on this idea, and NASA had already decided that a Soyuz docking with Skylab was also not an option any longer. These discussions continued, and eventually an Apollo-Soyuz docking was suggested, and this would lead to the Apollo-Soyuz Test Project (ASTP) of 1975.

In 1971 Chief of Flight Crew Operations, Deke Slayton, began the process of selecting crews for the upcoming Skylab missions. At that time, three missions were definitely scheduled with the possibility of two more. It had also been suggested that the crews should consist of one pilot/commander, preferably a flight experienced astronaut joined by two scientist-astronauts in order to maximize the scientific output from these flights. Slayton quickly put a stop to that idea; his feeling was that Skylab was a totally new kind of mission, and he wanted two pilot astronauts on each crew in case something went wrong. He came up with the following crew assignments based on those criteria.

|

Mission |

Commander |

Pilot |

Science-pilot |

|

|

Skylab 1 |

Prime |

Pete Conrad |

Paul Weitz |

Joe Kerwin |

|

Back-up |

Rusty Schweickart |

Bruce McCandless |

Story Musgrave |

|

|

Skylab 2 |

Prime |

Al Bean |

Jack Lousma |

Owen Garriott |

|

Back-up |

Vance Brand |

Don Lind |

Bill Lenoir |

|

|

Skylab 3 |

Prime |

Gerry Carr |

Bill Pogue |

Ed Gibson |

|

Back-up |

Vance Brand |

Don Lind |

Bill Lenoir |

|

|

Skylab Rescue |

Prime |

Vance Brand |

Don Lind |

|

Skylab 3 and 4 back-up crew |

Even these initial assignments had undergone some change. Walt Cunningham had originally been assigned as back-up commander for the first flight, but he choose to leave NASA rather than stick around for another two years as only a back-up. He was replaced by Rusty Schweickart, who in turn was replaced on the Skylab 2 and 3 back-up crews by Vance Brand. Also added at a later date was the possibility of a Skylab Rescue mission. This was the first time that planning a rescue mission had even been possible in NASA’s space program. It involved flying a special Apollo Command and Service module fitted with two extra couches underneath the outermost couches already installed; this was a small area that had been used as a sleeping space during Apollo moon missions. This modified CSM would be flown by a crew of two, and come back with five crewmembers after docking with the second port on Skylab.

It was at this point that some confusion entered the Astronaut Office concerning the design of the mission patches for Skylab. The official designation for the three manned flights was SL-2, SL-3, and SL-4, with the first unmanned launch of the lab itself designated SL-1. The crews had designed their patches according to this numbering, but were later informed by the Skylab Program Director that in fact their flights were being referred to as Skylab 1, 2, and 3, so the patches were changed. When the patches were submitted for official approval, they were rejected by NASA’s Associate Administrator for Manned Spaceflight, Dale Myers, because of their numbering, and he ordered them to revert to the original designations. However, it was too late for the crews to do this, as their clothing for their upcoming missions had already been stored on board Skylab ready for its launch. It was deemed far too expensive, and unnecessary to change the clothing and labels at this late stage, so although the office designations for the missions remained, the patches are labeled, 1, 2, and 3. Such are the difficulties of managing a space program!

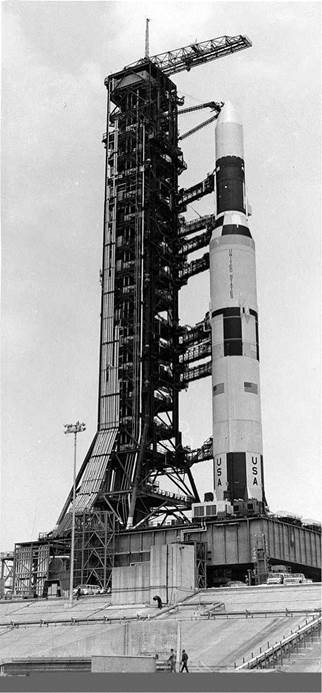

With the flight crews and launch dates now defined, some modifications were required to the launch pads to support the launch of the Saturn IB rocket. This had been used only once previously for a manned launch, when Pad 34 had been used for the Apollo 7 mission. As that pad was no longer available, it was decided to modify Pad 39B to accept the Saturn IB, and leave 39A largely as it was to launch the last ever Saturn V booster with the Skylab workshop on board. Given that most of the upper connections on the much shorter Saturn IB were the same as for the Saturn V that Pad 39B had been designed for, it was decided that the easiest modification to the pad would be to build a 127 foot high pedestal for the Saturn IB to sit on. This pedestal became known as the milkstool.

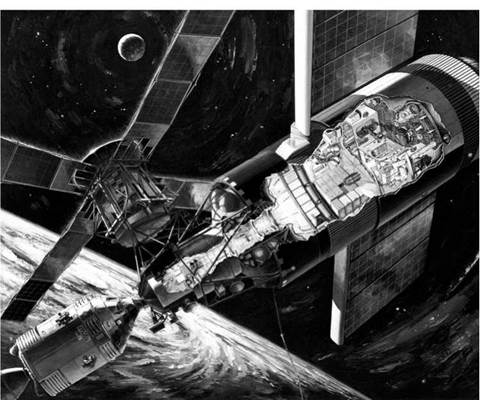

The Skylab workshop itself had undertaken quite a journey. Built originally as the second stage of the Saturn IB launch vehicle, it now had to be converted into a useable orbital workshop. S-IVB second stage number 212 had been built in 1966 by McDonnell Douglas, and its accompanying J-2 rocket engine built and tested during 1967 and then installed into stage 212 later that same year. At that point in time this stage was not assigned to a specific mission, so it was put into storage at McDonnell’s Huntingdon Beach assembly plant until March 1969. At the end of this period it was identified as being ideal for refurbishment as the Skylab orbital workshop. As 1969 progressed, the J-2 engine, thrust structures, and various other parts were removed to

|

Skylab |

leave the stage consisted only of its two fuel tanks. It took a further two years of work to prepare the interior of the hydrogen tank for human habitation in space. The second smaller tank, originally intended for liquid oxygen, would be used by the crew for storing all of their trash. By the end of 1972 the Saturn S-IVB stage 212 was ready to be launched as the primary Skylab workshop. At the same time, another S-IVB stage, number 515, this time from a Saturn V, had been identified as the back-up Orbital Workshop and had gone through the same conversion process as stage 212. It never flew, of course, and it was delivered to the Smithsonian Institution for display at the Air & Space Museum in Washington D. C., where it has been since July 1976.

Before any of the announced crews could visit the station, it was decided to run a full mission length simulation on the ground. This simulation would allow all the experiments and equipment aboard the station to be tested before launch. It would also help to alleviate any medical fears regarding the crew’s long-term exposure to a artificial closed ecological system. If there were any problems, it would be better that they happened first on the ground. In order to run the simulation as accurately as possible, a complete mock-up of the Skylab interior had to be built in an altitude chamber in order that the correct pressure and mixture of gases could be used. It was

|

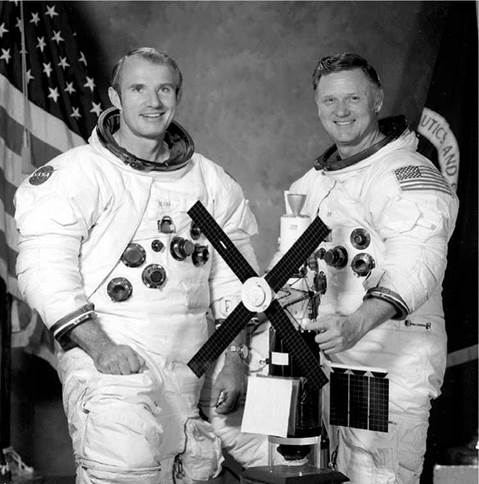

SMEAT crew |

decided to use the 20 foot diameter chamber at the Manned Spacecraft Center in Houston. The program was known as SMEAT, which stood for Skylab Medical Experiments Altitude Test. Originally planned to consist of two simulations, one lasting for 28 days and a second lasting for 56 days, it was decided to limit the program to just one 56-day test. The crew for the SMEAT test was to be selected from the pool of existing astronauts, but not to include any of the selected Skylab crews, their back-ups or support crew. Bob Crippen was selected as commander, with Karol Bobko as pilot and Bill Thornton as science-pilot. They designed their own mission patch, which featured the cartoon character Snoopy with a tightrope around his neck; this was said to reflect how they felt about some the medical experiments that were to be performed on them.

|

SMEAT patch |

On the 26th July 1972 the three men prepared to start their marathon simulation with a medical check before beginning a long pre-breathing period to purge nitrogen from their blood. During the “mission” the crew participated in all the experiments that the actual crews would perform in flight. This allowed them to discover any problems with procedures, and to set a baseline for the experiments that were to be performed in orbit. The test ended on 20 September 1972, and undoubtedly made a massive contribution to the success of the Skylab missions.

By the end of 1972 the Skylab program was ready for its first launch. The thirteenth and final Saturn V booster to be launched would be used to haul the Orbital Workshop into space, where it would be visited and lived in by three separate crews launched by Saturn IB boosters from an adjacent pad. With the crew of the first mission watching, the Saturn V lifted itself from Pad 39A, and at first, everything appeared to be quite normal.

Unfortunately just as the vehicle was passing through Max Q (a term for maximum aerodynamic pressure) about 70 seconds after launch, the first signs from telemetry showed that the booster was in trouble. The telemetry showed that the micrometeoroid shield and the number two solar array had already been deployed. This, of course, should have been impossible, for the Skylab workshop was still surrounded by the aerodynamic launch shroud. In fact, the shroud enclosed only the structures atop the OWS. The skin of the OWS was the S-IVB, which was exposed to the airflow. However, the Saturn V continued its pre-programmed path and delivered Skylab to orbit. It now remained to be seen what condition the lab was in. Initial telemetry suggested that there had been a major problem with the solar arrays, as the amount of power being generated by them was a small percentage of what it should have been. Clearly if the station could not generate enough power, it could not be occupied for any length of time. After more detailed investigation by NASA officials, it was determined that a design imperfection had caused the micrometeoroid shield to move away from its flush location against the workshop, and aerodynamic forces had then ripped the entire shield away, taking the left-hand solar array with it. It was uncertain whether the right-hand array had been similarly lost, or was trapped against the lab by debris from the departing shield. It was hoped that the

|

Skylab ready for launch |

latter was the case. Pete Conrad’s crew were stood down until they could be trained to free the trapped array. Unfortunately, the micrometeoroid shield was to have served as the thermal shield to keep the interior of the workshop cool. With its demise, the internal temperature was climbing steadily to the point where it would exceed the limits designated safe for human habitability. The obvious thing for ground controllers to do was to maneuver Skylab such that the area of bare skin was pointed away from the Sun in order to keep the internal temperatures under control. However, this also meant facing the remaining solar arrays, which were located on the Apollo Telescope Mount, away from the Sun, thus depriving the fledgling station of power. Eventually the Skylab controllers alternated the station between different attitudes in an effort to find the best compromise. A further complication caused by the increasing internal temperatures was the condition of the food supplies aboard the station for all three of its future crews. The temperature had risen to 54°C but it was determined that all of the canned food on board would survive such temperatures for quite a while if necessary. Further concerns affected the medical supplies and film—it was decided that the crews would carry fresh supplies with them.

Ultimately, however, it would fall to the first crew to make repairs to the station if the entire planned program was to be carried out. Many possible solutions for both the shield and the solar array problems were put forward, but most were not practical. Eventually 10 solutions were shortlisted, and after further deliberations this list was cut to two. It was decided to supply the first crew with both solutions. An improved Sun shield solution would be made ready for the second crew to install after the first crew had reported on the condition of the station. Testing of the components to be used by Conrad’s crew was carried out by Schweickart and Kerwin in the neutral buoyancy water tank at the Marshall Space Flight Center, to develop proceedures and verify that the equipment would function as anticipated. The Extravehicular Activities (EVAs) planned for Conrad’s crew were arguably the most complex, and the requirement to undertake them so early in the mission by a relatively untrained crew was greeted with nervousness by many within NASA. A simpler method for deploying a replacement temporary Sun shield was therefore devised that would enable the crew to remain inside the workshop, but for the stuck solar array there was no choice but to proceed with the planned EVA. The command module for the first crew would therefore be crammed with improvised and off-the-shelf tools to aid in the freeing of the remaining solar array.

Pete Conrad and his crew lifted off from the milkstool on Pad 39B on 25 May 1973, their destination the damaged Skylab Orbital Workshop. The rendezvous proceeded normally, and the first order of business was to fly around the workshop to carry out a visual inspection of the damage. After first docking with Skylab in order to conserve station-keeping fuel, the crew undocked to carry out a stand-up EVA. Conrad drew the command module up to the damaged solar array for a closer inspection; which revealed that a couple of metal straps were preventing the still intact array from deploying. They depressurized the command module and Paul Weitz and Joe Kerwin prepared to attempt to free the trapped wing. The procedure was for Kerwin to remain in the hatch and hold on to the legs of Weitz, who was hanging out of the hatch with a long-handled cutting tool. Every time Weitz

|

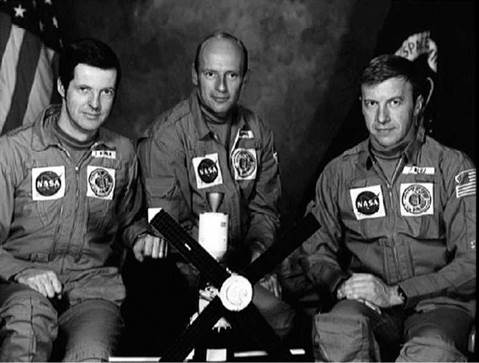

Skylab 2 crew |

attempted to cut the metal straps he would inadvertently pull the command module nearer to the hull of the Skylab, which meant Conrad at the controls had to fire thrusters to prevent a collision, which in turn made Kerwin’s task difficult. It just was not going to work. The crew now attempted to dock their spacecraft with Skylab’s axial docking port again, but this time they had trouble, only completing a successful docking after they had disassembled the command module’s docking mechanism and carried out repairs. Mission Control decided that this would be a good time for the crew to have a meal and a sleep period before entering the station.

When the crew did enter Skylab the next day, they found the temperatures to be extreme, about 125°F; Conrad likened it to the engine room on an aircraft carrier. Entering the workshop in short shifts and returning to the command module to cool off, the crew set about deploying the makeshift parasol. Making use of a small scientific airlock in the wall of the workshop on the sunward-facing side, they deployed the temporary sunshade in the fashion of a chimney cleaner extending his brush by adding a new section of rod and pushing it further up the chimney. Conrad and Weitz carried out the deployment, whilst Kerwin watched their progress from the command module. Once the parasol had been fully extended, it began to flatten itself in the warmth of the Sun, and soon the temperatures in the workshop

|

View of Skylab from Skylab 2 CSM |

began to drop; although it took about a week for the temperature to drop below 70 ° F. The workshop was now habitable, and the crew moved their belongings into their individual cabins and began to unpack the contents of the station in preparation for carrying out their assigned scientific duties.

Power, however, was a big problem; with only the solar arrays on the telescope mount available, Skylab had less than half the power it required. The crew would have to venture outside and attempt once more to free the trapped solar wing. Conrad and Kerwin ventured outside with the various tools that had been loaded on board their command module. One tool was a very-long-handled cutter of the type used by telephone repair men to remove branches that interfered with telegraph poles and wires. The crew had decided after their earlier inspection that this tool would be ideal to cut the metal straps that restrained the solar wing. However, when Kerwin tried to use it he found that it was impossible to place the cutting jaws precisely where he wanted them, partly owing to the length of the handles, but mainly because he was unable to get the leverage he needed for his own body in the weightless conditions. After many exhausting attempts, he noticed an attachment point on the hull and by connecting his dual tethers to this point, and one other, he discovered that he could “stand” on the hull with the tethers strained against him. This gave him the leverage and positioning that he needed, and he was able to snap first one of the restraining straps, and then the other. Almost unbelievably, the solar wing refused to deploy. Both men looked on in exasperation, until it was realized that the hinges were probably frozen and holding the wing in place. Kerwin decided to venture out into the middle of the wing and push against a rope that was tied to it, and eventually the hinges were freed and the wing began to deploy. Conrad, meanwhile, had been shot from the wing like an arrow; but his umbilical line caught him and he returned to the station hand over hand in time to see the wing fully deploy. Conrad and Kerwin reentered the station whilst delighted ground controllers confirmed that the wing was now fully deployed and generating electricity, Skylab was saved.

Conrad and his crew could now settle into more of a standard routine, more like the one originally envisaged. They immediately discovered that Skylab was big and roomy, much larger than any spacecraft they had previously experienced. To give some idea of its size, the interior usable volume of Skylab was about 361 m3, which is a fairly meaningless number; by comparison an average semi-detached three-bedroom house has a volume of about 270 m3. That made Skylab pretty big, but bear in mind that in your three bedroom house on Earth, in normal gravity, you only get to use the floor space of that 270 m3, any space above your head is essentially wasted. In orbit, in zero-g, all of that space is habitable whether its floor, ceiling, or wall. The early Salyut stations had little more than 100m3 of space so you can see that Skylab was large for its time, and in fact its internal size would not be surpassed until the Mir space station had been fully constructed twenty-five years later.

The hydrogen tank that the crew now lived in was split into two decks, if you imagine Skylab standing upright as it was on the launch pad with the workshop at the bottom, and the docking adapter and telescope mount at the top. The very first thing we see working from the bottom of our stack, is the original oxygen tank of the Saturn rocket stage, this tank has been basically left alone, and was used to store all of the crew’s rubbish. The crew put the rubbish into the tank via an airlock connector which ran between the oxygen tank and the much larger hydrogen tank. The “bottom” floor of the hydrogen tank contained the crew’s individual sleeping quarters, the ward room, the bathroom, an experimental rotating chair, and the airlock for the rubbish tank, as well as a shower, a first for any manned spacecraft. Each crewman had his own sleeping compartment, with a sleeping bag hung on one wall, and storage space for personal items. Pete Conrad found that he did not like the way his sleeping bag was hung because the airflow went up his nose, so he turned the sleeping bag around; of course it’s all the same in zero gravity. The wardroom contained a table that all three crewmen could assemble around with a separate area for each of them; this allowed them to heat their food with a kind of tray to eat from. In the center of the table there was a water dispenser, both for drinking directly from, or for rehydrating their food packs. The table also included a kind of bar stool arrangement for each man, but they found these very awkward to use as it meant that they had to conscientiously bend over the whole time, and their abdominal muscles quickly became tired. The shower, which many might think would be a very welcome addition to any spacecraft that you are going to spend a significant amount of time aboard, proved to be not as useful as hoped. The shower compartment was not a permanent glass structure that you might expect on Earth, but a collapsible enclosure to aid cleaning. In the absence of gravity the water had to be pressurized for it to “flow” from the shower head, and the water had then to be collected by means of a suction head much like a vacuum cleaner that was used to suck the water from the interior of the shower, and the astronaut. The crews found that whilst it was a pleasant experience to have this facility, it took a great deal of time to set-up, use, and clean up after, and they therefore used it less often than they otherwise might have. The bathroom was not quite such a chore to use, but the three crews did all find it a little odd that the designers had chosen to place the toilet on the wall, which meant that the crewman ended up facing the floor. In all other respects that system worked well, which was just as well, as the alternative meant reverting to the Apollo plastic bag method!

The main reason for the crew’s presence on board, of course, was to carry out scientific experiments. A great many of these were carried out on the crew themselves, to study the effects of long-term weightlessness on the human body. One of the other important roles of Skylab was to study the Sun. An entire suite of equipment had been designed for this purpose, and the crew trained extensively in its use. Once the power problems were solved, the crew were able to carry out their full schedule of Sun observations using the ATM (Apollo Telescope Mount).

An important milestone was achieved on 17 July when Conrad’s crew surpassed the 23-days-in-space mark set by the Soyuz 11 crew on board Salyut 1 in 1971. They spent their final week finishing the current experiments, stowing results for return to Earth, and getting the station ready to be unmanned for a period of time before the arrival of the next crew. Once the crew had separated from Skylab, another fly – around was carried out to photograph the condition of the station, then they fired the SPS engine to initiate the return home. The crew had completed 28 days in space, and Conrad was now the new spaceflight record-holder with over 1,179 hours in space. Years later, when asked, he would say that Skylab 2 was the mission that he was most proud of, and that when he thought about space, he always thought of Skylab and all of that room. Most people he met assumed that his mission to the moon would have been the highlight of his career, but as far as he was concerned Apollo 12 had gone by the numbers, and had been relatively routine; he would not trade it for the world, but it really had not been that exciting. Skylab was different; he and his crew had faced unknown problems, and surmounted them, and they had left the station able to continue the mission for which it had been launched, as well as achieving nearly all of the mission’s scientific objectives.

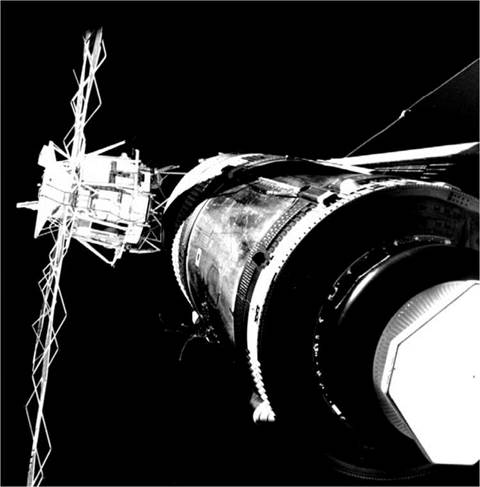

Skylab’s mission continued after the departure of the first crew. The ATM had been designed to be controllable from the ground, and therefore solar observations

|

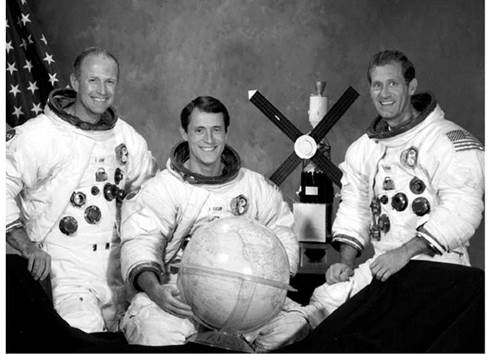

Skylab 3 crew in front of Pad 39B |

continued. Unfortunately, a primary gyroscope used to control the orientation of the station failed, and observations were stopped until the next crew could arrive. It was decided to bring forward the launch of Skylab 3 so that they could replace the failed gyro, and also install an improved sunshield, as controllers feared that the temporary solution deployed by Conrad’s crew was deteriorating faster than expected.

The Skylab 3 crew consisted, as planned, of commander Alan Bean, pilot Jack Lousma, and science-pilot Owen Garriott, and their command module was almost as packed with additional items as the first crew’s had been, partly because the intention was to increase the mission duration by three days, to the originally planned 56 days. The improved sunshade was one thing, but they also carried extra film canisters, extra food, various spare parts, including a replacement set of gyros. Launch was set for 28 July 1973, and the countdown proceeded smoothly. Only Bean had flown previously; Garriott and Lousma were rookies. Lousma fell asleep whilst waiting for liftoff. As he would later recall, “Just about thirty seconds before launch, you reach over to your buddies, shake their hands and wish them good luck, because their luck is going to be the same as yours!’’

Skylab 3 was launched flawlessly, and had no trouble docking with Skylab. After many checks, the crew entered the workshop to mark the first time that a space station had been reoccupied by a different crew. However, the mission had not been without some complications at this early stage. Lousma had started to suffer from some “stomach awareness”, or Space Adaption Syndrome as we now call it, shortly after reaching orbit, and later as they entered the station Bean and Garriott had also begun to suffer too. Bean had, of course, flown on Apollo 12 with no problems at all, and it caused some surprise in Mission Control when he reported feeling ill. The crew did their best to carry on with their duties, but inevitably fell behind schedule. The net effect was that Mission Control tried to give the crew additional rest time in an effort to speed their recovery, and also postponed the first planned EVA by 24 hours. Over the next couple of days, the crew slowly began to feel better and began to catch up on the schedule; however, the entire episode caused concern for mission planners, especially with the next Skylab crew—all rookies—scheduled for a longer mission.

The problems did not end there unfortunately. It had also been noticed early on that one of the thruster quads on the Apollo service module had sprung a leak, and eventually it was deactivated. The spacecraft was able to fly perfectly well with the three remaining quads. However, several days later a second quad also started to leak and had to be shut down. This still did not represent any immediate danger for the crew, as Apollo was quite capable of flying on two, or even one thruster quad, but it did cause concern that eventually all four quads might be rendered useless. NASA’s contingency planning came into its own at this point; a rescue mission had been planned for all three missions to Skylab, and it was this option that saved the mission. If there had been no possibility of a rescue mission, the Skylab 3 crew would have packed up and come home as soon as possible, whilst the two remaining quads were still operational. But the possibility of flying a rescue command module meant that both the crew and Mission Control could afford to wait and see. In the meantime, the rescue crew of Vance Brand and Don Lind rehearsed in the simulators and their modified command module was readied for flight. The engineers on the ground were able to determine that the leaks in the two thrusters were unrelated, and that there was nothing to suggest a systematic fault. The rescue crew were stood down, although they did spend time simulating the Skylab 3 return with only two working thrusters. Lind would later remark that he had effectively talked himself out of his first flight by showing that the Skylab 3 crew could return safely without the need for a rescue flight.

After these dramas, life settled into a gentler routine for the Skylab crew. There were a few equipment malfunctions that had to be attended to, but on the whole the rest of mission was quiet. Garriott and Lousma installed the improved sunshield during an EVA 10 days into the mission. The same pair also retrieved film cassettes from the ATM later in the mission, and later still Bean and Garriott retrieved more film cassettes and also retrieved a sample of the new parasol to determine its condition after a month’s exposure. When the time came for the crew to leave the station, they had more than completed their objectives, and after the initial problems with space sickness had subsided, had consistently been ahead of the flight plan, always asking for more work, and by the end of the mission they had in fact achieved over 150% of their targeted work. Whilst this was a fantastic achievement, it would not bode well for the crew that was to succeed them.

|

Skylab 3 rescue crew |

The crew for the third and final Skylab mission broke from Deke Slayton’s usual rules of crew selection; they were all rookies. Their mission had changed somewhat, too. A comet had been discovered that would approach the Sun toward the end of 1973, and the launch of the third crew was delayed from its original October launch date until November so that they could carry out observations using Skylab’s ATM and other instruments. The booster for the last Skylab mission had been sitting on the pad for some time, as it had originally been rolled out to serve as booster for the Skylab rescue mission; when this mission was stood down, the booster became the Skylab 4 launch vehicle. However, just five days from launch a routine inspection crew discovered cracks on the stabilizing fins of the first stage. Perhaps this was not surprising, as this stage had been manufactured over seven years earlier, but clearly it

|

Skylab 4 crew |

could not be launched in this condition. It was decided to replace the fins on the pad, which would take about a week. The crew faced a tight squeeze in their Apollo Command Module due to it being packed with additional items for the long mission ahead, most of it food to allow the length of the mission to be extended from the planned 70 days to 84 days if all else was well. The launch itself was routine and seven hours later the crew sighted Skylab and prepared to dock—which they had some difficulty with initially, but managed at the third attempt.

With the experiences of Al Bean’s crew very much in mind, Mission Control had ordered the astronauts to take more precautions against space sickness in order to prevent disruption to the early mission flight plan, and they took anti-sickness pills as soon as they reached orbit. It was also decided that the crew would have a sleep period before entering the station for the first time. Unfortunately, it was swiftly proved that this approach did not help, as Bill Pogue was overcome with nausea almost as soon as the rest period began, and relieved himself of his last meal. The crew made the first mistake of the mission when they decided not to mention Pogue’s symptoms to Mission Control. Confident that he would feel better before they entered the lab for the first time they simply explained that he had not felt hungry and had left most his last meal uneaten. This plan might have worked if it were not for the on-board automatic taping system which recorded the entire conversation and relayed it later to the ground, and most importantly to Chief Astronaut Alan Shepard. As a result Shepard talked directly to the crew commander, Gerry Carr, and voiced his opinion on what he called “a fairly serious error in judgement”. Carr realized the error of his ways and put his hands up and agreed that “it was a dumb decision”.

Despite the best efforts of the mission planners, Pogue’s sickness would impact the early activation of the station by limiting his participation with the rest of the crew. In fact, the planners seemed to assume that this crew could pick up at the same pace as Bean’s had left off, which ignored the fact that it took Bean’s crew several days to get near that pace of work. The planners also seemed to assume that procedures in space took the same amount of time as taken during training on the ground, and as hard as the crew tried to keep pace, they simply could not, and fell further behind the timeline set by the ground controllers. Even worse, the planners on the ground did not seem to realize that they were making things worse; they even added extra tasks to the crew’s day, causing them to fall even further behind, and consequently start to believe that they were not doing a good enough job. On the seventh day of the mission, Pogue and Ed Gibson carried out a planned EVA to replace film cartridges successfully, but even then the tired crew left some stowing away tasks until the next day. All in all, the first three weeks or so were very difficult. But things began to improve as the crew realized how to make things better, and better communicate those thoughts to the controllers on the ground. This was about the same period of time that Al Bean’s crew had taken to reach their peak efficiency, but this fact was apparently forgotten by the mission planners, who seemed to assume that the new crew could immediately start where the previous crew had left off. The crew desperately tried to remain on the timeline, and explain the problems to those on the ground, but their pleas went unheeded. The mission planners, for their part, always felt that the crew were about to reach their best performance level, and were therefore reluctant to reduce the workloads. After all, this was the last chance for these scientific experiments to be flown and NASA wanted to take advantage of every waking moment. It all came to a head after the crew had been in orbit for about six weeks. During a call with the crew’s boss, Deke Slayton, all of the problems were voiced and discussed, the ground were persuaded to ease off on the workload, and also leave some of the scheduling to the crew rather than providing a daily minute-byminute task list. This meant that the crew felt more in charge of their activity, and were able to follow a more “normal” day. The rest of the mission proceeded at a similar pace to the previous ones, and by the end of January 1974 the crew were making preparations to return home. The orbit of Skylab was raised slightly with a firing of RCS jets on the Apollo service module, in the hope that this might allow Skylab to survive for longer, and perhaps be visited again before its expected orbital decay in 1981 or 1982. The Skylab 4 crew landed about 5 hours after undocking having spent a total of 84 days and 1 hour in orbit.

The possibility of a Skylab revisit and re-boost mission would now be left to the space shuttle, which at this stage did not exist, so a choice had to be made between trying to preserve the station for some future visit by Apollo CSM or the space shuttle, or a mission to send a crew in Apollo to carry out a controlled re-entry burn to send Skylab to its destruction. There were some risks attached to the latter, as it involved the docked CSM firing its service module engine until Skylab had almost reached entry interface, which meant that a prompt undocking was a very important action; if the docking latches failed in some way the crew would follow Skylab to destruction! In part due to these risks, it had been decided to boost Skylab to a higher orbit before the final crew left, effectively deferring the decision until the early 1980s. Once the space shuttle program was underway, it was tentatively planned that during its third flight the shuttle would rendezvous with Skylab and attach a booster rocket to the docking port, at which time it would be decided whether to boost the station to a higher orbit once more, or send it to the bottom of the Pacific Ocean. Ironically, Jack Lousma of Skylab 3 was assigned to pilot the shuttle’s third mission, and revisit his old home. In the end, two factors decided Skylab’s fate. The first was the protracted development of the shuttle, it became clear over time that the shuttle would simply not be ready in time to save the orbiting station, especially as it’s orbit was deteriorating faster than expected owing to increased solar activity inflating the upper atmosphere and causing increased drag. Skylab would have to be left to make an uncontrolled re-entry sometime in 1979, and it seemed every nation in the world was worried that it would fall on them. Shortly before its crash to Earth, it was determined that Australia was the most likely target, and at least 25 tons of various parts of the station were predicted to survive the re-entry process. In the event, several parts did survive, and a young Australian claimed the $10,000 prize that a U. S. newspaper had offered as reward for any genuine Skylab parts. The largest items found were a door from one of the film vaults, and some oxygen and nitrogen tanks, and these along with various museum pieces like the back-up Skylab are all that remain of the United States’ first space station.

Was Skylab a success? The answer is both yes and no. Yes, because NASA successfully carried out a great deal of science during the three manned periods, and even during the unmanned intervals as well. For an agency that had no real experience of carrying out scientific experiments, other than those on the surface of the moon, and none at all over long periods of time, it was a very successful project. Detailed photography and data about the Sun was collected—enough to keep researchers busy for some years, human medical experiments, materials processing, and more besides, were all carried out with precision and accuracy by the various crews. On the other hand, Skylab was not a success, because the mission planners in particular seemed unable to learn from the experiences of previous crews. The work schedule for all of the crews was always unrealistic. It was an easy mistake to make on your first space station project; the Soviets had experienced similar problems after all with the early Salyut mission. Amazingly, NASA would be doomed to repeat these mistakes in years to come on board Mir and the International Space Station.