The First Satellites

The idea of “artificial moons” orbiting Earth was put forward by a few scientists and science-fiction writers in the early 1900s. In 1945, British science fiction writer Arthur C. Clarke suggested in a magazine article that three satellites orbiting Earth could act as relay transmitters for worldwide communications. The visionary Clarke now has a satellite orbit named after him.

By the 1950s, there were rockets capable of launching satellites, although these were being developed primarily as military missiles. The American Rocket Society and the National Science Foundation both suggested using satellites for the scientific study of space. These groups proposed that, to mark International Geophysical Year (19571958), the United States should launch a science satellite.

The Soviet Union announced that it also would launch a satellite, but few people in the West took this claim seriously. So it was a great surprise when, on October 4, 1957, the Russians launched the world’s first satellite, Sputnik 1. Orbiting Earth every 96 minutes, Sputnik 1 caused a sensation. An even greater surprise followed on November 3, 1957, with the launch of Sputnik 2, which was bigger still and carried a dog named Laika. The United

О The first satellite launched by the United States was Explorer 1, seen here being installed on its launch vehicle in January 1958.

States launched its first satellite, Explorer 1, early in 1958. The “space race” had begun in earnest.

The Soviet Union launched hundreds of Cosmos satellites and also Molniya communications satellites, but seldom released much information about them. U. S. space launches were more public, and satellites were usually designated by their function: scientific, weather, communications, navigation, or Earth observation. Only satellites for military use were kept secret.

Since the 1960s, France, China, Japan, Britain, India, and Israel have launched satellites with their own launch vehicles. Other nations have hired launches to put satellites into space. Once front-page news, satellites are now routine, with many commercial and multinational launches each year.

v

v

was founded in 1920. Two early U. S. airlines were Pan American World Airways (1927) and Trans World Airlines (founded as Western Air Express in 1925).

was founded in 1920. Two early U. S. airlines were Pan American World Airways (1927) and Trans World Airlines (founded as Western Air Express in 1925).

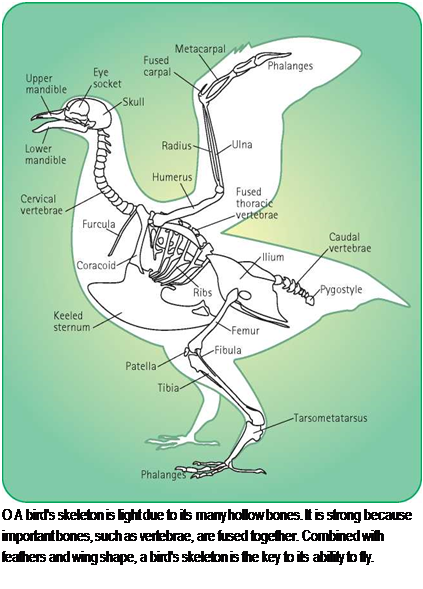

as swifts and swallows, have long, narrow wings, often swept back like a jet fighter. Soaring birds, such as vultures and buzzards, have broad wings. Gliders-the albatross, for example-have long, straight wings.

as swifts and swallows, have long, narrow wings, often swept back like a jet fighter. Soaring birds, such as vultures and buzzards, have broad wings. Gliders-the albatross, for example-have long, straight wings.