Bird Anatomy

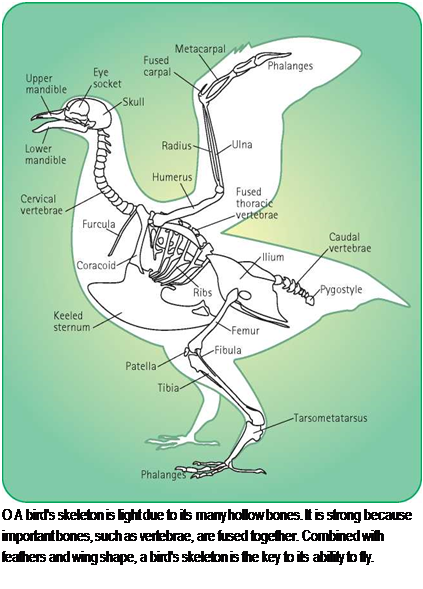

Some birds have as few as 900 feathers, while others have more than 25,000. This does not make much difference in their flying skills. The secret of flying is the bird skeleton. Bird bones are very light, but very strong-many bird bones are hollow. Because the bones are also fused (joined together), a bird has an amazingly strong frame, although it weighs little. Even the world’s heaviest flying bird-a bustard-weighs only 40 pounds (18.2 kilograms).

The largest muscles in a bird’s body work the wings (although in flightless birds, such as the ostrich, these big muscles work the legs). The wing muscles are in the chest, below the wing. The muscles are attached to the upper wing by tendons that work like pulleys. This streamlined body design gives the bird a high power-to-weight ratio, just like an aerobatic airplane. Its muscles provide the engine power to drive the wings. To fuel those muscles, most birds need a lot of food every day. Birds can inhale large amounts of air very quickly, using the oxygen to help provide energy for rapid flight.

A bird’s wings are equivalent to a person’s arms, with long “finger” bones carrying flight feathers, the longest feathers. The bird wing is curved like an airplane wing-slightly rounded on top, flatter underneath. This curved shape forces air to speed up when flowing over the top surface. The faster the airflow, the less air pressure there is above the wing. Because high-pressure air always moves to fill low-pressure space, the air beneath the wing moves upward. This movement creates lift beneath the wing, and the bird flies.

Wing shapes are a clue to how different birds fly. Fast-flying birds, such

as swifts and swallows, have long, narrow wings, often swept back like a jet fighter. Soaring birds, such as vultures and buzzards, have broad wings. Gliders-the albatross, for example-have long, straight wings.

as swifts and swallows, have long, narrow wings, often swept back like a jet fighter. Soaring birds, such as vultures and buzzards, have broad wings. Gliders-the albatross, for example-have long, straight wings.

Birds that need rapid takeoffs (like pheasants and prairie hens) and small birds that nest in shrubs or undergrowth usually have quite short, stubby wings.