Going Farther and Higher

Balloons were soon flying over the ocean. Frenchman Jean – Pierre Blanchard and American John Jeffries flew across the English Channel in 1785. In 1793 Blanchard completed the first balloon flight in the United States, traveling from Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, to Gloucester County, New Jersey.

Early balloonists learned to control flight upward or downward. By letting out air or gas, the balloonist could descend. Throwing out ballast (sand or lead weights) enabled the balloon (now lighter) to rise. The disadvantage of a balloon is that it cannot be steered-it drifts with the wind. Sails, oars, and even paddlewheels were tried for steering, all without success.

Balloon flights became popular entertainment, but they also had serious uses. The U. S. Army’s Balloon Corps used balloons for observation during the Civil War (1861-1865). Balloonists made the first scientific researches into the upper atmosphere. In the 1930s, Auguste

Piccard, a Swiss scientist, rode in a sealed cabin beneath a hydrogen balloon. He rose more than 50,000 feet (15,240 meters). In 1935 American balloonists Albert W. Stevens and Orvil A. Anderson ascended to 72,395 feet (22,066 meters). This record remained unbroken until the 1960s, when other balloonists in the United States reached

|

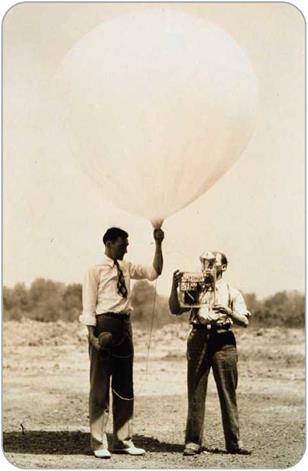

О Workers from the U. S. Bureau of Standards prepare to launch a weather balloon carrying a radiosonde in 1936. This was an early use of the radiosonde to measure air temperature and pressure. |

over 100,000 feet (30,480 meters). Unmanned balloons have flown as high as 170,000 feet (51,816 meters).