This flying machine designed by Bachem at Waldsee was basically a manned rocket, a term which shows the direction the planning was taking. Because of the very tight raw materials situation it was a surprise that, despite Julia, the Natter should now arrive on the scene. Although vaunted as disposable, after a mission the main components of the aircraft could be saved by parachute. Natter – pilot training was only 20 hours and limited to learning how to steer the machine and fly it into the enemy bomber fleet. The Waffen-SS was very keen on the Natter because of its speed, while the SS-FHA believed that the rocket aircraft could be used in bad weather, poor visibility and at night.

Everything was to be done to make Natter a lethal opponent for enemy bombers. The design of Gerat N, the title of the original rough sketch, was presented to the SS-FHA. Work to manage the technical side was assigned by OKL and the Chief-TLR. From the shadows the SS provided the logistical support: the SS-FHA (Amt X) was responsible for personnel, transport and other materials. Above all OKL brought to the project the technicaland tactical lessons learnt from the Me 163. Amt X was responsible for SS-Sonder – kommando ‘N’ as well as the Natter work group.

It was not very long before the Sonderflugzeuge (‘special aircraft’) Development Commission expressed grave reservations about machines such as the Natter. Director Robert Liisser, previously at Fieseler, was appointed by the Commission to head Biiro Liisser whose objective was to ensure that the Natter was quickly ready for series production. He was also responsible for maintaining contact with the individual research centres. In the late summer of 1944 he resigned to work with Heinkel on the Julia since in his opinion the vertical launch of the Natter was far less suitable for engaging enemy bombers than the less dangerous catapult launch of the Heinkel machine.

Liisser s departure caused a crisis for the Natter. In the short term, the Chief – TLR could find no suitable replacement for Liisser, nor were sufficient technical staff available for the project. Although the tactical possibilities were relatively good and the financial investment not large, the development of Julia, and a litde later Natter, were suspended by the Commission, although apparently the order was ignored and work proceeded as though nothing had been said. Through the influence of the SS-FHA the number of staff at Bachem Werke plus the SS special commando rose in stages to 475, and then 600, although there was still a shortage of aeronautical engineers to speed up the work on the Natter.

At the beginning of September 1944 flight testing of the Natter was laid down as follows. After successful tests with the Liegekranich and Habicht gliders by the NSFK, the DVT would make a thorough evaluation of the ‘flying-while-lying’ position by means of the Berlin B9 and FS 17. The Reich Gliding Training School atTrebbin would convert Kranich gliders from the upright to the recumbent-pilot position. A short flight programme would investigate the practical flight possibilities. At Trebbin, starts by winch and inclined ramps would also be tested. Experienced test-parachutists from the Rechlin E5 department would make several jumps from a Natter fuselage (classified as risky). A DFS 230 would be used as a Natter-Mistel to see how the Natter behaved when air-launched.

At the Travemiinde test centre ways were sought to save the lives of future Natter pilots by a new kind of ejector seat. In mid-1944 it was not clear how this could be effected for a pilot in the recumbent position. The engine tests were to be completed with the help of the Walter Werke, where the Natter engine had also been installed experimentally into an Me 163. During tests at altitude, courageous DVL specialists were to investigate if it were possible to reach 10,000 metres (33,000 ft) at a rate of climb of 200 m/sec (650 ft/sec) without oxygen equipment, remain for 30 seconds at the operational height and then endure the life-saving fall at over 250 m/sec (820 ft/sec). After the conclusion of the preliminaries an He 177 would be set up as a Natter-cainer to extend the radius of operations although as a rule the Natter would be ground-launched to intercept incoming marauders. These tests and firing the rockets in the nose were seen as extremely important.

The pilot’s position now changed from Erich Bachem’s first sketch, which had the pilot recumbent, to a crouching figure and then finally a pilot seated in the normal manner. The operational flight-test programme would consist of only five unmanned starts from a ramp, followed by 12 manned starts. For the subsequent firing programme, 10 Natters were planned.

Initially OKL wanted to instal a battery of RZ 65 spin-stabilised rockets of

65- mm calibre in the nose. The tests showed that these were woefully inaccurate – at the Tarnewitz test centre against a Bristol Blenheim fuselage at 200 metres range only one light hit was achieved from 20 rockets fired. The 19 misses were

|

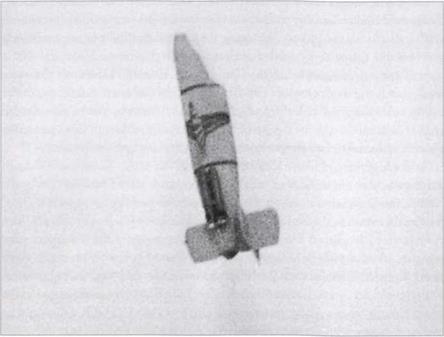

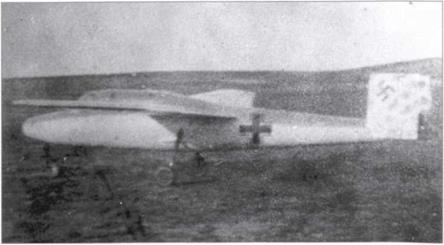

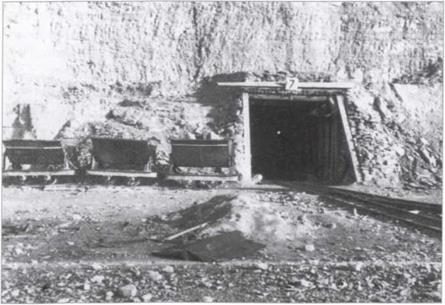

Take-off of the unmanned Ba 349 M-17 on 29 December 1944 on the Ochsenkopf (Heuberg) in Upper Swabia, south-west Germany.

|

up to 20 metres wide. Accordingly the RZ 65 idea was dropped and two MK108 guns considered instead, but the final armament remained long in doubt.

For trials of the new fighter and night flying by KdE test pilots or operational fliers at least 30 Natters were to be made available. In September 1944 an order was issued to build 15 ‘BP 20 aircraft’. The work was to be forced ahead by SS – Obersturmfuhrer Flessner, an engineer recovering from a wound, who began work with Bachem on 20 September 1944. As Himmler’s special charge d’affaires, SS-Obersturmfuhrer Gerhard Schaller was sent to the Heuberg to observe the initial Natter vertical starts.

By October 1944 the final Natter shape had crystallised. The completion diagrams of the BP 20, meanwhile re-designated 8-349 by the RLM, consisted of a disposable nose segment, a re-usable central fuselage section and the tailplane with rocket motor, both the latter being parachute-equipped. Propelled by an HWK 109-509 A-2 rocket motor, the machine was designed for sustained speeds up to 800 km/hr (500 mph) and a top speed of 1,100 km/hr (680 mph). Launch was to be from a tower or vertical ramp. Four SR 34 (later known as SG 34) rockets were to be located in pairs on either side of the fuselage to assist take-off. Before these could be used, a long list of technical and constructional problems had to resolved.

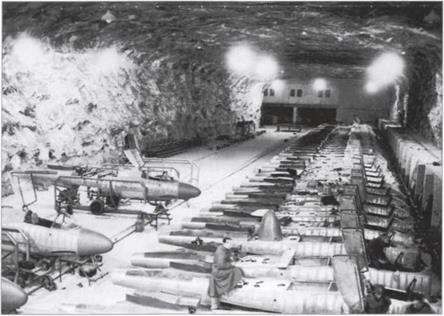

Testing of the first three Natter machines was set for 16 October 1944 between Bachem and the DFS at Ainring/Salzburg. The first airworthy unit, BM-1, was tried under tow to examine its general performance in flight, after which the tug pilot detached the Natter to parachute down. The unmanned second machine, BM-2, was taken up by an He 111 H and released by parachute. The third Natter had a tricycle undercarriage and could be tested extensively in flight. Bachem finally received the official contract for the Natter in the second half of October, after which steps were taken to build the launch tower at Karlshagen the following month, but the test centre was over-booked and an alternative in Mecklenburg was sought for ‘Test Group N The centre would be used for weapons testing for the future operational versions. Armament initially would be two MK 108 guns, 24 R4M or 48 Fohn rockets in the fuselage. While the final choice of gun was still under consideration, the fuselage of the fourth test machine, M4, was fitted with two MK 108s for trials, although as mentioned it could not be fitted as a standard to the series run because the weapon was in short supply and those there were went to the Me 262 A-la. The alternative was the spin-stabilised R4M rocket. The firm of Curt Hebei designed a lightweight firing assembly to fit 34 rockets into the Natter nose, and a Natter fuselage was brought to Reichenbach aerodrome firing ground at Schussenried for the tests. The Chief-TLR considered that the armament should be 28 and not the 34 R4Ms requested. From the late summer of 1944 work was carried out on the so- called ‘barrel-battery’, a fixed assemblage of 64 MK 108 barrels, this number being later reduced to 32 to save weight.

In a report from the Chief-TLR dated at the end of October 1944, differences of opinion were discussed respecting the operational possibilities of the Natter. Most experts believed that a Natter would be less at risk passing through an enemy bomber formation than a traditional piston-engined fighter. To shoot down a four-engined bomber it would require 60 rounds of З-cm ammunition fired in a long burst from two MK 108 guns, or 28 R4M air-to-air rockets, or fire from the 32 barrels of the barrel-battery. Range was between 200 and 500 metres for the MK 108,400 metres for the R4M and 250 metres for the barrel-battery.

The provisional firing trials at Schussenried on 10 November 1944 showed that the arrangement of the weapons installation was unsatisfactory for series production and a few days later the files for the MK 108 and barrel-battery were made available to DFS for further appraisal. It had been decided not to proceed with the R4M since these rockets were needed for other jet aircraft. More testing followed on 15 November. Ninety MK 108 rounds fired at a range of 100 metres gave a group of 0.7 square metres. After a revision by Rheinmetall the weapons installation worked flawlessly. It was also announced that day that Rheinmetall would need a Natter fuselage as soon as possible for the installation of a barrel – block drum from which 46 Fohn projectiles could be fired in a salvo.

The first two trial machines were to be completed by the end of November 1944 by Ebnerspacher of Esslingen near Stuttgart. On 30 October three Natter variants were being worked on. Variant A had a top speed of 880 km/hr (550 mph) though its operational ceiling of9,000 metres (29,500 ft) was inferior to Variant B. Variant C matched the speed and had longer range. After receiving the documents and several favourable opinions, on 27 November the Jagerstab ordered the first 50 trial aircraft. These were not to be suicide machines. Even in an attack at point-blank range, the substantial cabin armour would give the pilot a good chance of surviving defensive fire from numerous 0.5-inch guns. The Natter could operate up to a ceiling of 16,000 metres (52,500 ft). After the attack the pilot would dive to 3,000 metres (10,000 ft) from where he and the machine would descend to the ground by their respective canopies.

In December 1944 the first prototype, BP 20 M-l, was completed with a trolley undercarriage while the second and third prototypes had a fixed chassis. The first vertical start of an unmanned Natter, assisted by take-off rockets, took place on 8 December. Despite the unequal thrust of the four rockets the machine rose to 700 metres. On 14 December 1944 the first successful tow was made at Neuburg/Danube. Flight testing of the first two prototypes showed that the first assessments had been good although the aircraft attitude at release left something to be desired. The first vertical launch attempt on the Heuberg at Stelten am Kalten Markt used an upright start rail attached to a tower of metal scaffolding. On 18 December 1944 the test machine burned to a crisp when the arrest gear failed to disengage.

On 21 December Bachem Werke received a telex from the SS-FHA’s SS-Standartenfuhrer Fritz Czolbe, who had approved the highest priority for the Natter development, requesting all SS service centres, authorities and firms to support the project. The next day on a second unmanned launch the aircraft reached 750 metres despite an engine defect. The tail canopy deployed, the dummy pilot fell out and the rear segment of the aircraft descended to the ground by parachute. Acceleration during the launch procedure was calculated at 2.2G. The rate of climb was 700 km/hr (435 mph).

Progress was visible, and on 28 December 1944 SS-Untersturmfiihrer Minzloff of the SS Propaganda Company took photographs of the Natter to present Himmler with a more reliable impression of the new aircraft. Next day SS-Obersturmfuhrer Walter Klockner reported that the development did not have the speed specified by the SS-FHA. The head of Amt X was responsible for the work. Despite his influence, the frequent requests for technical personnel for the firm of Bachem Waldsee had not been met satisfactorily. The starting rockets continued to give problems. SS-Obersturmfuhrer Heinz Flessner, engineer and commander of SS-Sonderkommando ‘N’, made repeated demands for fuel for transport vehicles, but even everyday items such

as service insignia for the Sonderkommando and special identity documents were most difficult to procure.

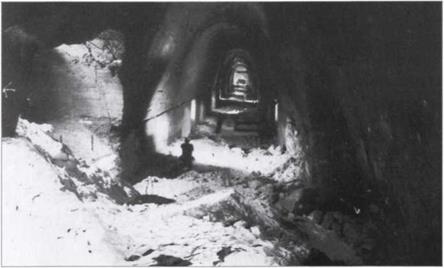

At the Heuberg meanwhile the vertical take-off trials continued. The third start on 28 December 1944 was made primarily to test the booster rockets. Prototype BP 20 M-17 was the first to reach an altitude of 3,000 metres, but the machine was destroyed in a heavy landing due to partial parachute failure. From 4 January 1945 orders were given that Natter trials were to be carried out at Neuburg/Danube, Horsching/Linz and Ainring/Salzburg, but there was nothing to be gained at this stage by rushing the development, and a second launch tower was planned at Ohrdruf in Thuringia to match the first at Heuberg. This work was under the direction of SS-Untersturmfiihrer Bodensteth. A shortage of200 sacks of cement for the foundations of the Ohrdruf tower caused substantial delay.

On 5 January 1945 the Riistungsstab cancelled the Natter and next day the Me 163. Testing of the Me 263 (Ju 248) was to proceed. At Bachem the

|

The only certain vertical take-off manned flight with the Natter was made by Lothar Sieber in Ba 349 M-23 on 1 March 1945 and resulted in his death.

|

cancellation notice was not taken very seriously, since the He P 1077 Julia had been dealt the same blow. All these projects had been pursued provisionally as ideas to be looked at within the framework of existing possibilities. A fire at Brodenbach where the starting rockets were manufactured caused a bottleneck in supply in January, however. To alleviate the situation, several simple wooden launch trolleys were devised to do away with fixed emplacements. Obersturm – fiihrer Klockner of the SS-Sonderkommando asked Obersturmfiihrer Kersten at SS-FHA Amt X for more men and a few cars and lorries. These were necessary for the transport of materials and supplies between Waldsee and the Heuberg.

By 20 January the requested workforce had still not arrived at Waldsee nor the supply of coke to heat the Bachem factory. The MK 108 barrel-battery and Fohn honeycomb launcher were to have been tested from 23 January on the Heuberg but, despite all efforts by Amt X, the ammunition failed to arrive. There was also a shortage of cement needed to improve the ramp on the Heuberg. Towing trials continued, the tug used on 27 January being the DFS aircraft He 111 H-6 (DG#RA).

Meanwhile the SS-Sonderkommando and Bachem Werke were working all out for the imminent Operation Crocus. This involved setting up ten mast ramps and preparing 15 Natter A-Is each with a Fohn launcher in the nose. Each installation fired a single rocket from a honeycomb of 24 cells. Most of the munitions for the first operation had not arrived by 27 January. The first firing position was set up close to the Autobahn at Holzmaden. The first Natter used against the Allied bombers was to be launched on 1 March 1945.

The machine factory at Esslingen was to supply the first three mast ramps by 20 February. After the only available Natter at Neuburg/Danube had been damaged, the flight test group was transferred from there to DFS at Ainring/Salzburg. Another free-flight machine had been completed and fitted out for tests while work continued round the clock on the Ba 349 A-l for Operation Crocus. It was hoped to have the first machine ready by 17 February; at one new machine per day the last would be ready by 3 March. To help out, the Waffen-SS sent another 12 technical workers, and Bachem Werke also received 11 experienced carpenters and mechanics.

An extraordinary effort was invested in Operation Crocus. Besides the urgently needed 6,500 litres of fuel for road vehicles, 2,500 litres of C-fuel and 5,000 litres ofT-fuel were required for the rockets. SS-Obersturmfiihrer Strasser was to obtain all this at the earliest opportunity using a Waffen-SS tanker. SS- Obersturmfiihrer Flessner attempted to procure at least seven tonnes of brown coal to keep the work going at Waldsee.

On 14 February works pilot Unteroffizier Hans Ziibert took off in prototype M-8 for the first free flight in a Natter Ba 349. He released from the He 111 H tug at 5,500 metres and began a free glide. His speed at 3,600 metres was 600 km/hr (12,000 ft/370 mph) and he landed safely in a soft field near the banks of the Danube at Neuburg. Test report No. 11 of 22 February mentions another unmanned test machine, M-22, due to fly that day, and M-23 scheduled for a manned flight from the ramp 24 hours later, but both starts were cancelled when M-22 was damaged. A problem-free launch with complete separation and dummy pilot ejection followed on 25 February. By the end of the month, the SS preparation for Crocus had advanced, due mainly to the arrival at the Waldsee workshops of an expert in electrical supply and heating from SS-FHA Amt X. Latent problems with the Natter steering and rocket motor were being overcome by the Siemens LGW (Aviation Equipment Works) and specialists sent by Walter Werke respectively.

Early in 1945 Major Edmund Gartenfeld, Kommandeur I./KG 200, began the groundwork for the Crocus unit. This included selecting the operational airfield and setting up the ground infrastructure. A flak officer was appointed for target finding and aircrew instruction. The aim now was for a test operation of at least ten Natter over the Stuttgart area by 20 March at the latest. A larger operation would have to await completion of the Ba 349 B-l. This variant, of which only one machine was being built when work was halted, had longer range than the A-l and double the armament.

On 1 March technical development of the Natter was handed over to the Luftwaffe Flak Development Division in close cooperation with the Waffen- SS. That day a first manned Natter launch was scheduled on the Ochsenkopf. That morning veteran Luftwaffe pilot Lothar Sieber climbed into Natter M-23 upright at the starting tower. Sieber had been at Bachem as a ‘test pilot’since 22 December 1944 and knew the risk he was taking. The former Leutnant Sieber had been reduced to the ranks for an offence against military discipline by a court-martial in the Moscow Luftgau jurisdiction. He had survived numerous dangerous assignments subsequently. At the end of November 1944 after one such mission Generaloberst Ritter von Greim had given Sieber his own Iron Cross First Class as a token of his admiration and promoted him to Ober – leutnant. Sieber was the world’s first pilot to achieve a vertical take-off but it cost his life. He may have dislocated a cervical vertebra as he threw off the cockpit cover in an attempt to bale out after losing orientation in low cloud. In the Waffen-SS Sonderkommando report of 2 March, SS-Obersturmfuhrer Schaller thought that he might have wrenched his head against the cockpit cover at launch. Because of this tragedy it was decided to suspend manned vertical takeoffs until an almost fully automatic Natter operation was possible. On 8 March, M13 flew an unmanned automated test followed on 10 March by M-34, and it was hoped that the A-l series production could now proceed.

At the beginning of March, M-25 was ready for use as the second manned aircraft with rocket motor, M-33 would be the unmanned test. Other Natters such as M-31 were being equipped with Siemens LGW steering. Of these aircraft, seven were launched from the 9.5 metre ‘telephone pole’ ramp, the first being the unmanned M-32. Apart from testing on the Ochsenkopf, work to make the Natter operational at the beginning of March 1945 went full out despite the severe shortage of rocket fuel. Through the SS-FHA, Bachem had attempted to obtain a higher priority for raw materials for Natter construction and the works’ cars and lorries, and more rocket fuel to enable flight testing to be continued, and to plan the first operational missions. On Kammler’s orders, Sonderkommando ‘N’ was to receive all conceivable support. Intensive

construction of the Natter continued at Hirth and in the Thuringian Forest, but the extra workers requested urgently by Bachem from the Luftwaffe and SS never found their way to Waldsee.

For the imminent Crocus operation, the SS was planning to use machines M-51 to M-65 against Allied bombers over Wurttemberg. On 8 March at a Natter conference attended by representatives from OKL and the Chief-TLR and aides of the Reichsfiihrer-SS it was agreed that the Luftwaffe would take over management of the project because the SS-FHA lacked technical expertise and Natter trials ‘in action in the coming weeks would not be possible in view of the existing problems. How the situation on the ground would look then was anybody’s guess. On 13 March Himmler ordered, with immediate effect, that enough fuel must be made available for 20 Natter starts monthly. Should all go well until July 1945 he would argue for much more, although in any case there was enough C-fuel and T-fuel for the next six months, he thought.

Probably the last interim report on the Natter development was that dated 23 March 1945 mentioning the Malsi equipment which had a target-finding range of 21 kilometres up to a ceiling of 12 kilometres.

A Natter launch was to proceed in the following manner. On detection of the enemy approach by the flak command post the director equipment would be tuned

in. On receipt of the signal the Natter pilot would switch on his on-board systems, flying controls and turbine. He would then report himself ready with the words: ‘Meldung, fertigf (‘Announcement: ready!’)- When the attack bearing had been calculated, the ramp would be traversed accordingly. On the command ‘Achtung 1’, the crew would secure the chassis and take cover. The pilot would then unlock the autopilot and code in the flying time to target on the clock. After working up the motor slowly for four to five seconds he would make a final check of the control stick and pedals. At the commands ‘Achtung’ and ‘Start’ the pilot pushed the ignition button and grasped the handgrips in the cockpit. The Natter would then fly a direct course to the enemy. This never happened in practice.

On 28 March Generalmajor Walter Dornberger, head of Arbeitsstab Domberger at Peenemiinde, ordered the cessation of the Natter project. This did not go down well with the Waffen-SS, and the SS-FHA demanded its continuation with some vehemence, new vertical take-off trials having been prepared on the Ochsenkopf. On 2 April 1945 the unmanned M-52 was launched, and after a brief flight dived into the ground near Bensingen village. Probably the last Natter rose on 10 April and came down near Ebingen (Albstadt). The dummy pilot and machine components were retrieved with their parachutes.

As Allied forces advanced, personnel of the Ochsenkopf test ground were evacuated to Bad Worishofen on 15 April for a possible transfer to Bavaria. In mid-April an attempt was made to remove the Bad Waldsee operation to Bad Worishofen. On 24 April the first French tanks arrived at Waldsee, where engineer Zacher had sunk 15 rocket motors in the Waldsee. American troops found most of the project files and four Natters at St Leonhard in Austria. A damaged tug aircraft was impounded at Aiming. At Bachem about 30, mostly Ba 349 A-ls, left the Hirth workshops, while one of ten pre-series machines was being manufactured at Nabern-Teck. This run was an А-series conversion with improved armament. Only one was near completion by March 1945. A variant in the advanced planning stage with demountable wings to be series-built as Ba 349 C was never realised although the wings were reported to be under manufacture at the war’s end.

One last Natter may have been fired from the mast at Ohrdruf just before the capitulation but the machine did not rise far and was apparently crushed after leaving the ramp. Allied troops then occupied the area and the military depot.

By mid-April 1945 there had been 18-20 vertical starts and at least five successfixl flights under tow, some with a release of the warp and a problem-free parachute landing. In trials ten Natters were lost to accidents, two machines to rocket-motor fires and a third to fire on the launch mast.

Fuel production in underground or bombproof factories could not be expected until the autumn, and even then the output would be small. The Wehrmacht could rely on 50,000 tonnes of oil from underground centres in January 1946. But of what use would that be to facilities such as the underground works at Ebensee (Traunsee), now under hasty construction, if no more oil was arriving for refining? Even the last oilfields near Zistersdorf north of Vienna had meanwhile been seized by the Red Army.

Fuel production in underground or bombproof factories could not be expected until the autumn, and even then the output would be small. The Wehrmacht could rely on 50,000 tonnes of oil from underground centres in January 1946. But of what use would that be to facilities such as the underground works at Ebensee (Traunsee), now under hasty construction, if no more oil was arriving for refining? Even the last oilfields near Zistersdorf north of Vienna had meanwhile been seized by the Red Army. Anybody who knew the true facts must have realised before the beginning of 1945 that because of Allied air superiority over the Reich, and the great industrial and manufacturing strength of the Allies, the time for anything other than local defence was past, yet even in the spring the effort was still being made to produce extreme high performance and therefore very costly aircraft in numbers. This included light jets, well-armoured Jabos and

Anybody who knew the true facts must have realised before the beginning of 1945 that because of Allied air superiority over the Reich, and the great industrial and manufacturing strength of the Allies, the time for anything other than local defence was past, yet even in the spring the effort was still being made to produce extreme high performance and therefore very costly aircraft in numbers. This included light jets, well-armoured Jabos and

The dream of building the most powerful air force in the world was shattered, a fact scarcely

The dream of building the most powerful air force in the world was shattered, a fact scarcely