Plans for a New Luftwaffe

|

I |

n the spring of 1945 the war was as good as lost. The Allied armies were within the old Reich borders and the Soviets were heading for Berlin. Resistance on the various fronts was in a state of collapse. Yet, on the aviation production front, the design bureaux pressed on, churning out plans which had no hope of realisation. What use were these paper tigers with no bauxite, chrome, manganese, electric current, hardly any fuel and chaos in communications? Many decision-makers seem to have been ignorant of the problems. They continued to make plans as in the glory days of the Luftwaffe and the Blitzkrieg. The dreaming did not end even in April 1945.

|

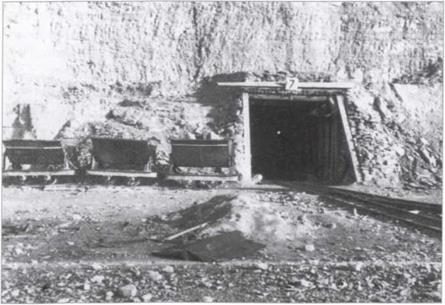

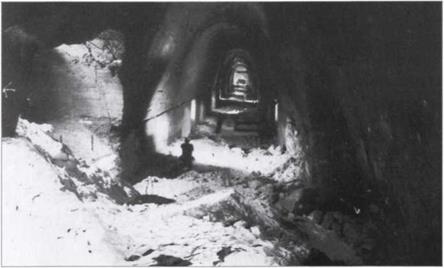

Gallery entrances such as this show that materials were in too short supply for progress in the short term. With starving slave-workers and dwindling resources the targets set in underground factories could never be met. |

Symptomatic of the situation were talks attended by high-ranking officers on 10 February 1945 in Berlin. For the first time they were forced to acknowledge, with no ifs and buts, that nearly all hydro-electric plant had been wrecked by bombing, and that no more fuel was forthcoming until the end of March.

Fuel production in underground or bombproof factories could not be expected until the autumn, and even then the output would be small. The Wehrmacht could rely on 50,000 tonnes of oil from underground centres in January 1946. But of what use would that be to facilities such as the underground works at Ebensee (Traunsee), now under hasty construction, if no more oil was arriving for refining? Even the last oilfields near Zistersdorf north of Vienna had meanwhile been seized by the Red Army.

Fuel production in underground or bombproof factories could not be expected until the autumn, and even then the output would be small. The Wehrmacht could rely on 50,000 tonnes of oil from underground centres in January 1946. But of what use would that be to facilities such as the underground works at Ebensee (Traunsee), now under hasty construction, if no more oil was arriving for refining? Even the last oilfields near Zistersdorf north of Vienna had meanwhile been seized by the Red Army.

The stark reality was that between February and the autumn of 1945 only 16,000 tonnes of B-4 and C-3 fuel, and 43,000 tonnes of J-2, would become available. This represented a

monthly output of 2,300 tonnes for piston-aircraft (B-4 and C-3) and 6,000 tonnes for jets (J-2) and would not suffice for even the most essential operations. Aircraft production was to be pruned down to the As 234, He 162, Me 262 and Та 152 only. Even Bf 109 and Fw 190 production was to cease, the production line to be run down as fast as Me 262s and Та 152s became available to replace them. Even Ju 88 production was to come to a halt in the late autumn of 1945 so as to maintain material reserves.

From the early summer of 1945,500 He 162s and Me 262s, 370 Та 152s and 50 As 234s would roll off the lines monthly. Such numbers spelled closure for most operational Geschwader and the remaining tactical forces could expect no better output of new machines than replacements for losses. At the beginning of 1945, reconnaissance aircraft, fighters and Jabos were given priority in the queue for fuel. Bombing missions no longer entered the picture. Several fighter Geschwader were also in line for the chop, and many of the remainder, including KG 76, would have been reduced. In the summer air transport capacity was to have been cut to six Gruppen. By the end of 1945, transport and parachute operations would not be possible and pilot training would also have come to an end.

With a resumption of production and assembly in underground plant the planners hoped to reinstate the disbanded units perhaps from the beginning of 1946. In the meantime there would have been fuel enough for some reconnaissance missions and a maximum of 75 Me 262 flights daily, not much to cope with the Allied bomber fleets.

Anybody who knew the true facts must have realised before the beginning of 1945 that because of Allied air superiority over the Reich, and the great industrial and manufacturing strength of the Allies, the time for anything other than local defence was past, yet even in the spring the effort was still being made to produce extreme high performance and therefore very costly aircraft in numbers. This included light jets, well-armoured Jabos and

Anybody who knew the true facts must have realised before the beginning of 1945 that because of Allied air superiority over the Reich, and the great industrial and manufacturing strength of the Allies, the time for anything other than local defence was past, yet even in the spring the effort was still being made to produce extreme high performance and therefore very costly aircraft in numbers. This included light jets, well-armoured Jabos and

multi-seater all-weather bombers with up to four jet turbines. That the production of the core He 162 and Me 262 jets was hamstrung by desperate logistical problems appears not to have struck the decision-makers.

|

One must therefore ask why they could not see that the war was lost. Was it from loyalty to the German leader, from a desire not to recognise the facts, or for personal reasons? There is really only one answer. From the generals down to the simple soldier, the belief existed that the end of the war would be a rough period and then things would go on as before. They recalled the motto at the 1918 Armistice: ‘The Kaiser goes, the generals remain.’ The Fiihrer and those who bore too high a burden of guilt would have to depart. Aviation, the Luftwaffe, would survive, perhaps with restrictions and prohibitions. In time new aircraft designs would be needed, for already the first cracks between the Allies were visible. Most of the Luftwaffe leadership had not been involved in war crimes and had only done their duty. Now they and everybody else stood before the abyss.

The dream of building the most powerful air force in the world was shattered, a fact scarcely

The dream of building the most powerful air force in the world was shattered, a fact scarcely

|

|

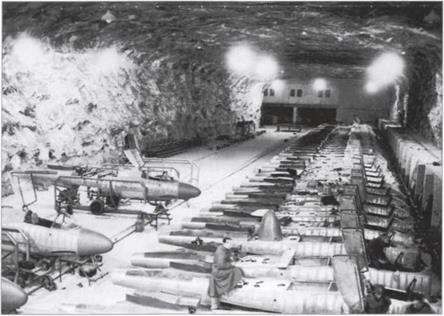

The enormous aircraft assembly hall at Maulwurf a former salt warehouse at Tarthun near Stassfurt. |

perceived in the spring of 1945. As long as the possibility of producing a single new aircraft still existed, work continued; and as long as a single drop of fuel could be obtained, flying continued. In desperation, pilots dived on bridges or rammed enemy bombers. The majority of the crews waited on the ground. It might make sense to try to avoid being killed at the last moment – too many had already been lost – or to try not to become involved in the vortex of the final battles, defending a trench impossible to hold. This went also for the Home Front. Many ‘adventurous’projects came into being simply to protect the planners against being drafted into the Volkssturm. This was often a decision taken by firms. War factory owners could see the time ahead when they would become free entrepreneurs, and their businesses would need a core of experienced workers and an intact management team. So it came about that project departments and design offices, such as at Heinkel-Siid, were kept going as long as possible. When the time came to shift, the staff were evacuated with their assignments and loaded into trains for shipping off to ‘safe’backwaters as yet unoccupied. The situation for forced labour and prisoners was of course quite different.