In 1988, Hughes was granted a development contract to add a Moving Target Indicator (MTI) capability to ASARS. However, the actions of Saddam Hussein interrupted operational tests of the system, by the 17 RW.

After the Gulf War, tests were successfully completed in October 1991 and the ASARS MTI became operational four years later. Now the system is capable of locating moving targets in search or spot modes.

After much Air Force deliberation, it was decided to upgrade the U-2 fleet with the General Electric F’101- GE-F29 turbofan engine. Of similar thrust to the J75, the newer engine promised to be much cheaper to maintain and was significantly lighter, with a much improved fuel consumption rate, thus restoring valuable performance lost through the expansion of the sensor package. It was first flown by Ken Weir in 80-1090 on 23 May 1989 and on 28 October 1994, a delivery ceremony w’as held at Palmdale, when the first three conversions were handed back to the Air Force, the engine having been redesignated in the meantime the FI 18.

Despite President Bush’s optimistic remarks about the establishment of a new world order, following the collapse of communism in the Soviet Union, continued political instability in various parts of the world has ensured that the capabilities of the U-2 reconnaissance system are as much in demand today as they were back in 1956.

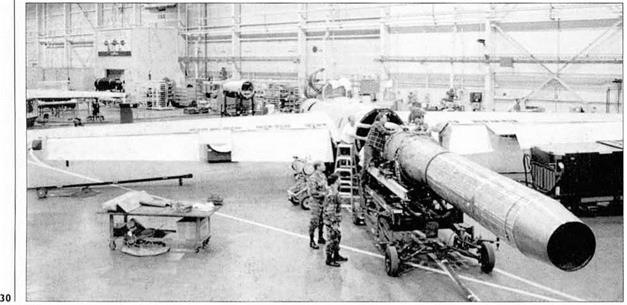

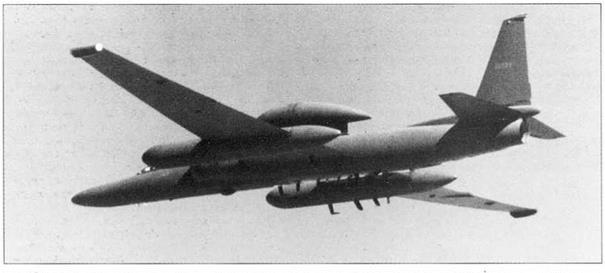

Below In all, 25 TR-1 As. two TR-1 Bs and two ER-2s were built using ‘White World’ money, at the Lockheed Martin Skunk Works plant at Palmdale – in addition, seven U-2Rs and a dualcontrol U-2R (T) were built ‘in the black’. (Lockheed Martin)

|

|

|

Mindful of the subsonic vulnerability of the U-2 to developing Soviet SAM systems, the Agency’s Richard Bissell contacted Kelly Johnson in the Autumn of 1957, and asked if the Lockheed Skunk Works team would conduct an operational analysis into the relationship of an aircraft’s interceplibility, as a function of its speed, altitude and radar cross section (RCS). As Kelly was already immersed in related studies, he agreed to accept the project; the results of w hich concluded that flight at supersonic speed and extreme altitude, coupled with the use of radar absorbent materials (RAM) and radar attenuating design, greatly reduced, but not negated, the chances of radar detection and a successful interception. Encouraged by these results, it was agreed that further exploratory work should be conducted. During the closing months of 1957, the Agency invited Lockheed Aircraft Corporation and

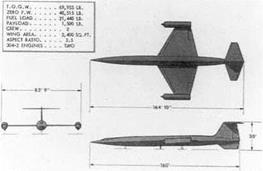

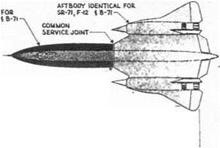

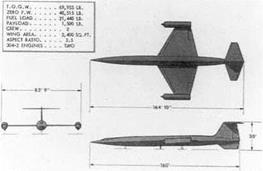

Above right With studies conducted by Pratt & Whitney and the Skunk Works at an advanced stage, Kelly Johnson proposed a liquid hydrogen propelled U-2 follow-on design to Lt Gen Donald Putt, during a Pentagon meeting in early January 1956. This Special Access Required programme, codenamed ‘Suntan’ developed the original CL-325 design into the CL-400. On paper, capable of Mach 2.5 at 100,000ft it was finally cancelled in February 1959, due primarily to lack of design stretch and logistical problems concerning the positioning of its highly volatile fuel. However the proposal led directly to a series of hydrocarbon designs that would take aerospace into a new era. (Lockheed Martin)

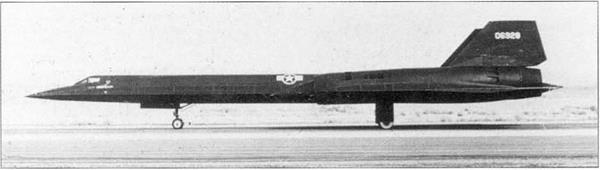

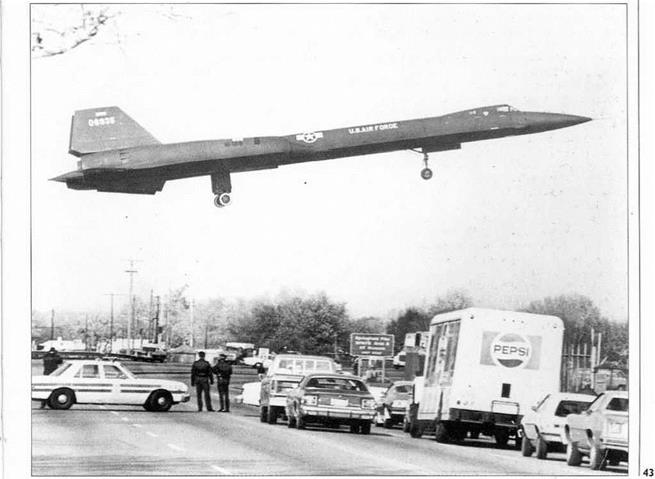

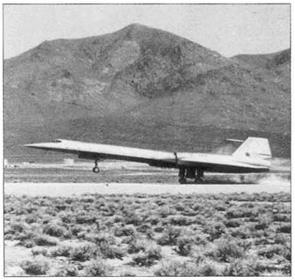

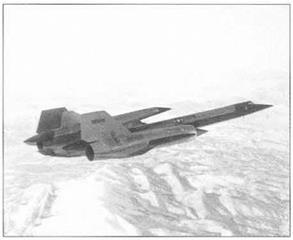

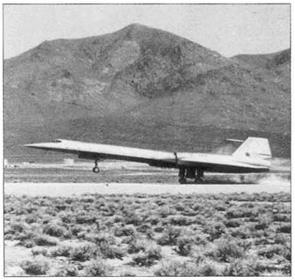

Opposite top A shot taken early in the A-12 test programme depicts a bare titanium aircraft landing at Area 51.

the Convair Division of General Dynamics to field to – t

the Convair Division of General Dynamics to field to – t

them non-funded, non-contracted design submissions for m a reconnaissance gathering vehicle, which adhered to the SJ aforementioned performance criteria. Both companies accepted the challenge and were assured that funding would be forthcoming at the appropriate time. For the next twelve months, the Agency received designs that were both developed and refined, all at no expense!

It was however, readily apparent to Bissell that the cost of developing such an advanced aircraft would be both high-risk and extremely expensive; government funding would be a prerequisite and to obtain this, various high – ranking government officials would have to be cleared into the programme and given concis, authoritative presentations on advances as they occurred. He therefore assembled a highly talented panel of six specialists under the chair of Dr Edwin Land. Between 1957 and 1959 the panel met on some six occasions, usually in Land’s Cambridge, Massachusetts office. Kelly and General Dynamics’ Vincent Dolson were at times in attendance, as w’erc the Assistant Secretaries of the Air Force, Navy and

It was however, readily apparent to Bissell that the cost of developing such an advanced aircraft would be both high-risk and extremely expensive; government funding would be a prerequisite and to obtain this, various high – ranking government officials would have to be cleared into the programme and given concis, authoritative presentations on advances as they occurred. He therefore assembled a highly talented panel of six specialists under the chair of Dr Edwin Land. Between 1957 and 1959 the panel met on some six occasions, usually in Land’s Cambridge, Massachusetts office. Kelly and General Dynamics’ Vincent Dolson were at times in attendance, as w’erc the Assistant Secretaries of the Air Force, Navy and

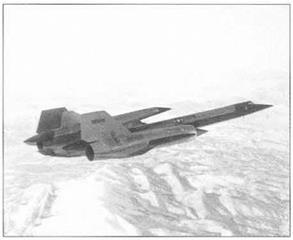

Above When deployed to Kadena under operation Blackshield, A-12s sported an overall black scheme, carrying no national insignia and bogus serials. (CIA)

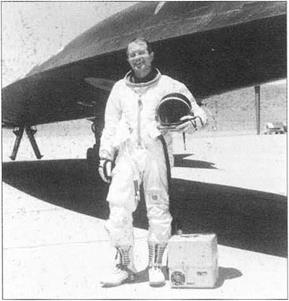

Below Agency pilot Ken Collins ejected safely from ‘926 on 24 May 1963. He is seen here wearing a David Clark S-901 full pressure suit. (CIA)

other select technical advisors. Code-named project Gusto by the Agency, Lockheed’s first submission, Archangel, proposed a Mach 3 cruise aircraft with a range of 4,000 nautical miles at altitudes of between 90-95,000 ft. This, together with his Gusto Model G2A submission, was well received by the Programme Office, as Kelly noted later. Convair on the other hand prepared the Super Hustler; Mach-4 capable, ramjet-powered when launched from a B-58 and turbojet assisted for landing. As designs were refined and re-submitted, the Lockheed offerings became shortened to A, followed by an index number, these ran from A-З to A-12. The design and designations from Convair also evolved and on 20th August 1959, final submissions from both companies were made to a joint DoD/Air Force/CIA selection panel. Though strikingly

different, the proposed performance of each aircraft was on a par.

On 28 August 1959, Kelly was told by the director of the programme that Lockheed’s Skunk Works had w’on the competition to build the U-2 follow-on. The next day they were given the official go-ahead, with initial funding of S4.5 million approved to cover the period 1 September to 1 January 1960. Project Gusto was now at an end and a new code name. Oxcart, was assigned. On 3 September, the Agency authorised Lockheed to proceed with anti – radar studies, aerodynamic, structural tests and engineering designs.

The small engineering team, under the supervision of Ed Martin, consisted of Dan Zuck in charge of cockpit design, Dave Robertson fuel system requirements, Henry Combs and Dick Bochme structures, Dick Fuller, Burt Mc. Master and Kelly’s protege Ben Rich.

The ambitious performance sought in the new aircraft can’t be overstated: the best front-line fighter aircraft of the day were the early century-series jets, like the F-100 Super Sabre and F-101 Voodoo. In a single bound, the A-12 would operate at sustained speeds and altitudes treble and double respectively, of such contemporary fighters’ limits. The technical challenge facing the Skunk Works team was vast and the contracted time scale in which to achieve it was incredibly tight. Kelly would later remark that virtually everything on the aircraft had to be invented from scratch. Operating above 80,000 feet the ambient air temperature was minus 56 degrees Centigrade and the atmospheric air pressure just 0.4 pounds per square inch. But cruising at a speed of a mile every two seconds, airframe temperatures would vary from 245 to 565 degrees Centigrade,

Sustained operation in such an extreme temperature environment, meant lavish use of advanced titanium alloys, which account for 85 per cent of the aircraft’s structural weight, the remaining 15 per cent was comprised of composite materials. The decision to use such materials was based upon titanium’s ability to withstand high operating temperatures. It weighs half as much as stainless steel but has the same tensile strength; in addition, conventional construction was possible using fewer parts – high strength composites weren’t available in the early sixties. The particular titanium used w’as B – 120VCA, which can be hardened to strengths of up to 200 Ksi. Initially the ageing process required 70 hours to achieve maximum strength but, with careful processing techniques, this was reduced to 40 hours. A rigorous (and expensive) quality’ control programme was set up, wherein

Top left Aircraft ‘932 was lost during a functional check flight (FCF) just prior to being redeployed back to the United States on 5 June 1968; its pilot. Jack Weeks, was killed in the incident,

(CIA)

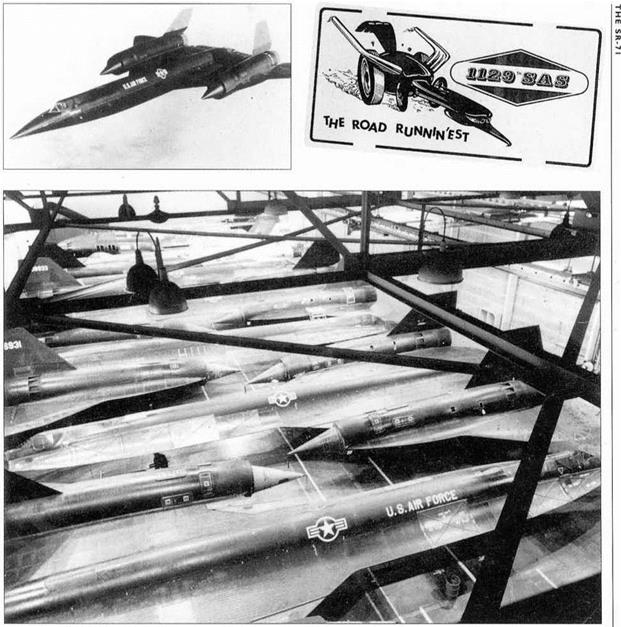

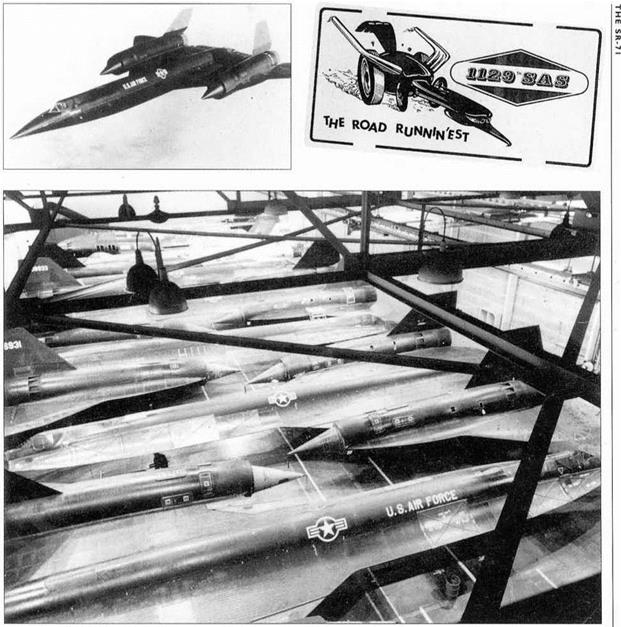

Top rightThe classified unit designation of the CIA. A-12 desert dwellers, was the I 129th Special Activities Squadron, The Road Runners’. (Paul Crickmore Collection)

Above When the A-12 programme was cancelled, the remaining aircraft were flown from Area 51 to Palmdale and placed in storage. (Lockheed Martin)

for every batch of ten or more parts processed, three samples were heat treated to the same level as those in the batch. One was then strength-tested to destruction, another tested for formabilitv and the third held in reserve should processing be required. With more than 13 million titanium parts manufactured, data is available on all but a few. Using this advanced material involved a steep learning curve and it wasn’t long before problems arose. Titanium is not compatible with chlorine, fluorine or cadmium. A line for example, drawn on sheet titanium with a Pentel pen, will eat a hole through it in about 12 hours – all Pentel pens were recalled from the shop floor. Early spot welded panels produced during the summer had a habit of failing, while those built in the winter lasted indefinitely. Diligent detective work discovered that to

|

prevent the formation of algae in the summer, the Burbank water supply was heavily chlorinated. Subsequently, the Skunk Works washed all titanium parts in distilled water. As thermodynamic tests got underway bolt heads began dropping from installations; this, it was discovered, was caused by tiny cadmium deposits, left after cadium-plated spanners had been used to apply torque. As the bolts were heated in excess of 320 degrees Centigrade, their heads simply dropped off. Remedy: all cadium-plated tools were removed from tool boxes.

Another test undertaken studied thermal effects on large titanium wing panels. An element 4ft x 6ft (1.2 x 1.8m) was heated to the computed heat flux expected in flight and resulted in the sample warping into a totally unacceptable shape. This problem was resolved by manufacturing chordwise corrugations into the outer skins. At the design heat rate, the corrugations merely deepened by a few thousandths of an inch and on cooling returned to the basic shape. Kelly recalled he was accused of “trying to make a 1932 Ford Trimotor go Mach 3”, but added that “the concept worked fine”. To prevent this titanium outer skin from tearing when secured to heavier substructures, the Skunk Works developed stand-off clips, this ensured structural continuity while creating a heat shield between adjacent components.

Chosen powerplant would be the Pratt & Whitney JT11D-20 engine (designated J58 by the US military). This high bypass ratio afterburning engine was the result of two earlier, ill-fated programmes: Project Suntan (see p34, caption) together with Pratt & Whitney’s JT9 singlespool high pressure ratio turbojet rated at 26,0001bs in afterburner and developed for a US Navy attack aircraft, which was also axed. Nevertheless, the engine had already completed 700 hours of full-scale engine testing and results were very encouraging. As testing continued however, it became apparent that due to the incredibly hostile thermal conditions of sustained Mach 3.2 flight, only the basic airflow size (400 lbs per second of airflow) and the compressor and turbine aerodynamics of the original Navy J58 P2 engine could be retained (even these were later modified). The stretched design criteria, associated with high Mach number and its related large air-flow turn-down ratio, led to the development of a variable cycle, later known as a bleed-bypass engine; a

Above Pictured at Area 51 with another A-12 just visible behind the gantry. M-21 .Article 134, serial 60-6940, is seen with a D – 21 mounted on its dorsal pylon. (Lockheed Martin)

Above right To aid ‘Mother/Daughter’ separation, a cylinder of compressed air was carried in the pylon. (Lockheed Martin)

Be/owThis shot, believed to be that of the ill-fated М-21, serial 60-6941, shows the aircraft in a later overall black scheme.

(Lockheed Martin)

concept conceived by Pratt & Whitney’s Robert Abernathy. This eliminated many airflow problems through the engine, by bleeding air from the fourth stage of the nine-stage, single-spool axial-flow compressor. This excess air was passed through six low-compression-ratio bypass ducts and re-introduced into the turbine exhaust, near the front of the afterburner, at the same static pressure as the main flow.

This reduced exhaust gas temperature (EGT) and produced almost as much thrust per pound of air as the main flow, which had passed through the rear compressor, the burner section and the turbine.

Scheduling of the bypass bleed was achieved by the main fuel control as a function of compressor inlet temperature (CIT) and engine rpm. Bleed air injection occurred at a CIT of between 85 and 115 degrees Centigrade (approximately Mach 1.9). To further minimise stalling the front stages of the rotor blades at low engine speeds, moveable inlet guide vanes (IGVs) were incorporated to help guide airflow to the compressor. These changed from an axial, to a cambered position, in response to the main fuel control, which regulated most engine functions. In the ‘axial’ position, additional thrust was provided for take off and acceleration to intermediate supersonic speeds, the IGVs then moved to the ‘cambered’ position, when the CIT reached 85 to 115 degrees Centigrade. Should IGV ‘lock-in’ fail to occur upon reaching a CIT of 150 degrees Centigrade, the mission was aborted.

When operating at cruising speeds, the turbine inlet

|

|

temperature (TIT) reached over 1100 degrees Centigrade; this necessitated the development of a unique fuel, developed jointly by Pratt & Whitney, Ashland Shell and Monsanto, known originally as PF-1 and latterly as JP-7. Having a much higher ignition temperature than JP-4, standard electrical ignition systems were useless. Instead a chemical ignition system (CIS), was developed, using a highly volatile pyrophoric fluid known as tri-ethyl borane (TEB). Extremely flash sensitive when oxidised, a small TEB tank was carried on the aircraft to allow engine afterburner start-up both on the ground and when aloft; the tank was pressurised using gaseous nitrogen, to ensure the system remained inert. Liquid nitrogen carried in

three Dewar flasks situated in the front nose gear well was also used to provide a positive ‘head’ of gaseous nitrogen in the fuel tanks. This prevented the depleted tanks from crushing as the aircraft descended into the denser atmosphere, to land or refuel. In addition, the inert gas reduced the risk of inadvertent vapour ignition.

Oxcart received a shot in the arm on 30 January 1960, when the Agency gave Lockheed ADP the go-ahead to manufacture and test a dozen A-12s, including one two – seat conversion trainer. With Lockheed’s’ chief test pilot, Louis W Schalk now on board, work on refining the aircraft’s design continued in parallel with additional construction work at Area 51. A new water well was drilled and new recreation facilities were provided for the construction workers, who were billeted in trailer houses. A new 8,500 ft runway was constructed and 18 miles of off-base highway were resurfaced to allow half a million gallons of PF-1 fuel to be trucked in every month. Three US Navy hangars together with Navy housing units were transported to the site in readiness for the arrival of the A-12 prototype, expected in May 1961. However, difficulties in procuring and working with titanium, together with problems experienced by Pratt & Whitney, soon began to compound and the anticipated first flight date slipped. Even when the completion date was put back to Christmas and the initial test flight postponed to late February 1962, the first J58s would still not be ready. Eventually Kelly decided that J75 engines would be used in the interim to propel the A-12 to a ‘half-way house’ of

50,0 ft and Mach 1.6, this action took at least some of the pressure off the test team.

The flight crew selection process evolved by the

Pentagon’s Special Activities Office representative (Col Houser Wilson) and the Agency’s USAF liaison officer (Brig Gen Jack Ledford, later succeeded by Brig Paul Bacalis), got under way in 1961. On completion of the final screening, the first pilots were William Skliar, Kenneth Collins, Walter Ray, Alonzo Walter, Mele Vojvodich, Jack Weeks, Jack Layton, Dennis Sullivan, David Young, Francis Murray and Russ Scott (only six of the above were destined to fiv operational missions).

Pentagon’s Special Activities Office representative (Col Houser Wilson) and the Agency’s USAF liaison officer (Brig Gen Jack Ledford, later succeeded by Brig Paul Bacalis), got under way in 1961. On completion of the final screening, the first pilots were William Skliar, Kenneth Collins, Walter Ray, Alonzo Walter, Mele Vojvodich, Jack Weeks, Jack Layton, Dennis Sullivan, David Young, Francis Murray and Russ Scott (only six of the above were destined to fiv operational missions).

These elite pilots then began taking trips to the David Clark Company in Worcester, Massachusetts, to be outfitted with their own personal S-901 full pressure suits –

Bbove WhenTagboard was cancelled, two B-52Hs of the 4200th Test Wing, at Beale AFB, continued working with the D-2ls, which required rocket boosters to propel them to their cruise speed and altitude. (Lockheed Martin)

Be/owThe North American F-108 Rapier was to have been an Improved Manned Interceptor (IMI) capable of Mach 3. It was cancelled due to escalating costs. (Rockwell International)

just like those worn by the Mercury and Gemini astronauts. In late 1961, Col Robert Holburv was appointed Base Commander of Area 51, his Director of Flight Operations would be Col Doug Nelson. In the spring of 1962 eight F-101 Voodoos, to be used as companion trainers and to pace-chase, two T-33s for pilot proficiency and a C-130, for cargo transportation, arrived at the remote base. A large ‘restricted airspace zone’ was enforced by the Federal Aviation Agency (FAA), to enhance security around ‘the Area’ and security notices were brought to the attention of North American Air Defence (NORAD) and FAA radar controllers, to ensure that fast-moving targets seen on their screens weren’t discussed. Planned air refuelling operations of Oxcart aircraft would be conducted bv the 903rd Air Refuelling Squadron, located at Beale AFB, and equipped with KC – 135Q_ tankers which possessed separate ‘clean’ tankage and plumbing to isolate the A-12s’ fuel from the tankers’ JP4, and special ARC-50 distance-ranging radios for use in precision, long distance, high-speed join ups.

|

With the first A-12 now at last ready for final assembly, the entire fuselage, minus wings, was created, covered with canvas and loaded on a special 8100,000 trailer. At 2.30am on 26 February 1962, the slow moving convoy left Burbank and arrived safely at Area 51 at 1.00pm, two days later. By 24 April, engine test runs together with low – and medium-speed taxi tests had been successfully completed. It was now time for Lou Schalk to take to the aircraft on a high-speed taxi run that would culminate in a momentary lift off and landing roll-out onto the dry salt lake-bed. For this first ‘hop’ the stability augmentation system (SAS) was left uncoupled; it would be properly tested in flight. As A-12 article number 121 accelerated down the runway, Lou recalled:- “I had a very light load of fuel so it sort of accelerated

really fast… I was probably three or four per cent behind the aft limit centre of gravity when I lifted off the airplane, so it was unstable… Immediately after lift-off, I really didn’t think I was going to be able to put the airplane back on the ground safely because of lateral, directional and longitudinal oscillations. The airplane was very difficult to handle but I finally caught up with everything that was happening, got control back enough to set it back down, and chop engine power. Touchdown was on the lake bed instead of the runway, creating a tremendous cloud of dust into which 1 disappeared entirely. The tower controllers were calling me to find

Below Developed for the F-108, the Hughes ASG-18 radar intercept system, together with its GAR-9 missile, remained under development and both were flight tested in this specially modified B-58, nicknamed ‘Snoopy Г, due to its extended nose profile. Note camera pods under outboard engines to record missile separations. (Paul Crickmore Collection)

Bottom Kelly, up at Area SI, stands next to the third and final YF-I2A interceptor, Article 1003, serial 60-6936. (Lockheed Martin)

out what was happening and I was answering, but the UHF antenna was located on the underside of the airplane (for best transmission in flight) and no one could hear me. Finally, when I slowed down and started my turn on the lake bed and re-emerged from the dust cloud, everyone breathed a sigh of relief.”

Two days later Lou took the Oxcart on a full flight. A faultless 07:05am take off was followed shortly thereafter by all the left wing fillets being shed. Constructed from RAM, luckily these elements were non-structural and Lou recovered the aircraft back to Area 51 without further incident.

On 30 April – nearly a year behind schedule – Lou took the A-12 on its ‘official’ first flight. With appropriate government representatives on hand the 59-minute flight took the aircraft to a top speed and altitude of 340kts and 30,000ft. On 4 May, the aircraft went supersonic for the first time, reaching Mach 1.1. Kelly began to feel confident that the flight test programme w’ould now progress rapidly, even recovering some time lost during the protracted manufacturing process. Another Lockheed test pilot, Bill Park joined the Skunk Works team to share the burden with Lou. On 26 June, the second A-12 arrived at Area 51 and was immediately assigned to a three-month static RCS test programme. The third and fourth aircraft arrived during October and November, the latter was a two-seat A-12 trainer, nicknamed ‘the Goose’ by its crews. The aircraft was powered throughout its life by two J75s. On 5 October, another milestone was achieved when the A-12 flew for the first time with a J58, (a J75 was retained in the right nacelle until 15 January 1963, when the first fully J58-powered flight took place).

When Randy Anderson’s U-2 was shot down by an SA-2 over Cuba on 27 October 1962, the U-2’s vulnerability was once again demonstrated in spectacular fashion. The significance of the incident was certainly not lost on

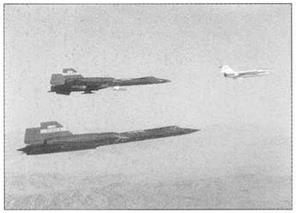

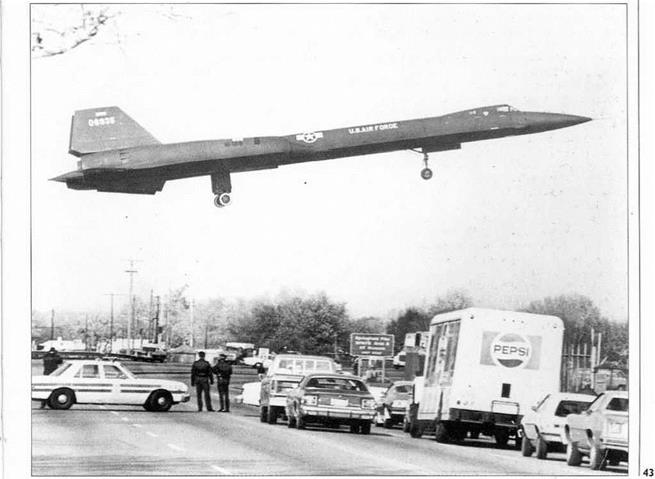

Above YF-12 A prototype, Article 1001, serial 60-6934, makes a low, fast pass for the cameras. Note the extended ventral fin together with the fins under its engine nacelles to improve longitudinal stability, together with the under-side camera pods to record missile separation and the IR sensor in the forward chine below the cockpit. (Lockheed Martin)

Below Boeing JQB-47E-45BO, serial 53-4256, was one of a number of remotely piloted B-47 drones used to evaluate missile and radar performance. It was operated by the 3214th drone maintenance Squadron, at Eglin AFB, during the YF-12 trials off Florida. Note stencilling. (Paul Crickmore Collection)

Right When the YF-12 programme was cancelled Col J Sullivan and Col R Uppstrom ferried the aircraft to Wright-Patterson AFB where it is now on permanent display at the Air Force Museum as the sole surviving example. (Lockheed Martin)

intelligence communities involved in Oxcart and the successful prosecution of that programme now became a matter of highest national priority.

A third Lockheed test pilot, Jim Eastham, was recruited into Oxcart, but still the programme was beset with problems, most of which were focused around the engines and Air Inlet Control System (AICS). The AICS regulated massive internal air flow throughout the aircraft’s vast flight envelope, controlling and supplying air to the engines at the correct velocity and pressure. This was achieved using a combination of bypass doors and translating centre-body spike position. At ground idle, taxying and take-off, the spikes were positioned in the full- forward position, allowing air to flow unimpeded to the engine’s compressor face. In addition, supplementary flow was provided through the spike exit-louvres and from six forward bypass exit-louvres. Early tests revealed that the engine required an even greater supply of air when operating at low power settings. This deficiency was overcome by installing additional bypass doors just forward of the compressor face. The size of these variable-area ‘inlet ports’ was regulated by an external slotted-band and could draw air through two sets of doors. The task of opening or closing these doors was manually controlled by the pilot initially, but this was accomplished much later automatically, when a Digital Automatic Flight Inlet

Control System (DAFICS) computer was developed. – i

Together, the forward bypass doors and the centre-bodv m spikes were used to control the position of the normal £

shockwave just aft of the inlet throat. To avoid the loss of ^ inlet efficiency, caused by an improperly positioned shockwave, the wave was captured and held inside the converging-diverging nozzle slightly behind the narrowest part of the ‘throat’, allowing the maximum pressure rise across the normal shock. Once airborne with landing gear retracted, the forward bypass doors closed automatically.

|

At Mach 1.4 the doors began to modulate automatically to obtain a programmed pressure ratio between ‘dynamic’ pressure at the inlet cowl on one side of the ‘throat’ and ‘static’ duct pressure on the other side. At 30,000ft and Mach 1.6, the inlet spike unlocked and commenced its rearward translation, completing its full aft movement of 26 inches at designated speed Mach 3.2 (the inlet’s most efficient speed). Spike scheduling was determined as a function of Mach number, with a bias for abnormal angle of attack, angle of side slip, or rate of vertical acceleration. The rearward translation of the spike gradually repositioned the oblique shock wave, which extended back from the spike tip, and the normal shockwave, standing at right angles to the air flow, and increased the inlet contraction ratio (the ratio between the inlet area and the ‘throat’ area). At Mach 3.2, with the spike fully aft, the

‘capture-airstream-tube-area’ had increased 112 per cent (from 8.7sq ft to 18.5 sq ft), while the ‘throat’ restriction had decreased to 46 per cent of its former size (from 7.7 sq ft to 4.16 sq ft).

‘capture-airstream-tube-area’ had increased 112 per cent (from 8.7sq ft to 18.5 sq ft), while the ‘throat’ restriction had decreased to 46 per cent of its former size (from 7.7 sq ft to 4.16 sq ft).

A peripheral ‘shock trap’ bleed slot (positioned around the inside surface of the duct, just forward of the ‘throat’ and set at precisely two boundary layer displacement thickness) ‘shaved’ off seven per cent of the inlet airflow and stabilised the terminal (normal) shock. This was then rammed across the bypass plenum, through 32 shock trap tubes, spaced at regular intervals around the circumference of the shock trap. As the compressed air travelled through the secondary passage, it firmly closed the suck – in doors while cooling the exterior of the engine casing before exhausting through the ejector nozzle. Boundary’ layer air was also removed from the surface of the centre – body spike at the point if its maximum diameter. This potentially turbulent air was then ducted through the spikes hollow supporting struts and dumped overboard, through nacelle exit louvres. The bypass system was thus able to match widely varying volumes of air entering the inlet system, with an equal volume of air leaving the ejector nozzle throughout the entire speed range of the aircraft.

The aft bypass doors were opened at mid Mach to minimise the aerodynamic drag which resulted from dumping air overboard through the forward bypass doors. The inlet system created internal pressures which reached 181bs per square inch when operating at Mach 3.2 and 80,000ft, where the ambient air pressure was only 0.4lbs per square inch. This extremely large pressure differential generated

Above Between 11 December 1969 and ЗI October 1979, NASA and the US Air Force embarked upon a joint high altitude test programme which required the use of two YF-12s and an SR-71. YF-12 60-6936 however was lost on 24 June 1971; both Lt Col ‘Jack’ Layton and Systems Operator Maj Bill Curtis ejected safely. SR-71 A, Article 2002, serial 64-17951 was redesignated YF-12C for political reasons and given the serial number 60-6937. (NASA)

Below The NASA flight test team were (left to right) Ray Young, Fitzhugh Fulton. Donald Mallick and Victor Horton. (NASA)

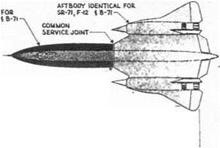

Right This Skunk Works document dated 6 April 1967, shows what the Air Force could have had – a Mach 3.2 reconnaissance aircraft, SR-71- a bomber, B-7I – and interceptor, F-12. (Paul Crickmone Collection) .

a pressure gradient, which in turn created a forward thrust vector, resulting in the forward inlet producing 54 per cent of the total thrust. A further 29 per cent was produced by the ejector, while the J58 engine contributed only 17 per cent of the total thrust at high Mach.

Inlet airflow disturbances resulted if the delicate balance of airflow conditions that maintained the shockwave in its normal position were upset. Such disturbances were called ‘unstarts’. These disruptions occurred when the normally-placed supersonic shockwave was ‘belched’ forward from a balanced position in the inlet throat, causing an instant drop in inlet pressure and thrust. With the engines mounted at mid-semi-span, the shockwave departure manifested itself in a vicious yaw toward the ‘unstarted’ inlet. Sometimes these were so violent that crew members’ helmets would be knocked hard against the canopy framing. To break a sustained unstart and recapture the disturbed inlet shock wave, the pilot would have to open the bypass doors on the unstarted inlet and return them to the smooth-flowing, but less efficient position that they had occupied prior to the disturbance.

Early A-12 test flights involved increasing the aircraft’s speed by increments of one tenth of a Mach number and manually selecting the next spike position. If the inlet dynamics worked well, the aircraft was decelerated and recovered back to ‘the Area’; there the dynamics would be further analysed and incorporated. More often however there would be a mismatch between spike position and inlet duct requirements and a vicious unstart would result. In all, it took 66 flights to push the speed envelope out from Mach 2.0 to Mach 3.2 and it wasn’t until pneumatic pressure gauges, installed on the inlet systems to sense pressure variations of as little as one-quarter of a pound per square inch, were replaced by an electrically controlled system from aircraft number nine (60-6932) onwards, that the incidence of unstarts plummetted.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]() Having moved from Laughlin to Davies-Monthan AFB, Arizona on 12 July 1963, the 4028th SRS compliment of reconnaissance gathering platforms increased substantially when an international agreement was reached to discontinue all above ground nuclear weapons testing and all HASP aircraft were re-configured accordingly.

Having moved from Laughlin to Davies-Monthan AFB, Arizona on 12 July 1963, the 4028th SRS compliment of reconnaissance gathering platforms increased substantially when an international agreement was reached to discontinue all above ground nuclear weapons testing and all HASP aircraft were re-configured accordingly.

the Convair Division of General Dynamics to field to – t

the Convair Division of General Dynamics to field to – t It was however, readily apparent to Bissell that the cost of developing such an advanced aircraft would be both high-risk and extremely expensive; government funding would be a prerequisite and to obtain this, various high – ranking government officials would have to be cleared into the programme and given concis, authoritative presentations on advances as they occurred. He therefore assembled a highly talented panel of six specialists under the chair of Dr Edwin Land. Between 1957 and 1959 the panel met on some six occasions, usually in Land’s Cambridge, Massachusetts office. Kelly and General Dynamics’ Vincent Dolson were at times in attendance, as w’erc the Assistant Secretaries of the Air Force, Navy and

It was however, readily apparent to Bissell that the cost of developing such an advanced aircraft would be both high-risk and extremely expensive; government funding would be a prerequisite and to obtain this, various high – ranking government officials would have to be cleared into the programme and given concis, authoritative presentations on advances as they occurred. He therefore assembled a highly talented panel of six specialists under the chair of Dr Edwin Land. Between 1957 and 1959 the panel met on some six occasions, usually in Land’s Cambridge, Massachusetts office. Kelly and General Dynamics’ Vincent Dolson were at times in attendance, as w’erc the Assistant Secretaries of the Air Force, Navy and