The Apollo lander

The CSM was a streamlined and sturdy craft, designed to ascend through the atmosphere of Earth, and. in the case of the command module, withstand a punishing re-entry. In contrast, the lunar lander was a true spacecraft because it was entirely incapable of flight in an atmosphere.

Knowm as the lunar module (LM). its construction w:as entrusted to the Grumman Aircraft Engineering Corporation. This was a truly exotic ship in which every aspect of its major systems pushed the know-how7 of the engineers who designed it. When originally conceived, it was called the lunar excursion module and therefore received

|

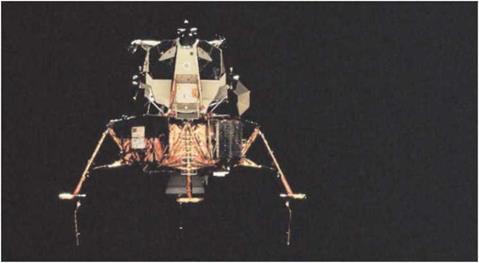

Orion, the Apollo 16 LM, prior to its descent to the lunar surface. (NASA) |

the acronym LEM. However, in 1965 managers decided that the use of excursion was too flippant as it suggested that the crews were going on a vacation. The name was shortened to lunar module but the pronunciation as ‘lem’ stuck.

The LM needed to be sturdy enough to withstand the acceleration and vibration of a launch from Earth and the shock from a rough landing on the lunar surface. Yet it also had to be as light as could humanly be achieved in order not to outweigh the ability of both the Saturn V and the CSM to deliver it to lunar orbit. Its largest engine had to be throttleable to provide adequate control of the astronauts’ descent to the lunar surface without the aid of wings or runways. Its flight path was controlled by two small computers in an age when such machines tended to occupy entire floors of buildings. Its engines had to be utterly reliable, even though the propellant systems operated at extreme pressures.

Prior to Apollo no one had dealt with the realities of designing a lunar module, which meant that Grumman could start with a clean sheet. Even before they won the LM contract, their engineers had produced preliminary designs. They then worked through several iterations before settling on the final spacecraft. The need for the LM to be a two-part ship was a corollary of the LOR concept. It operated as one vehicle until the moment of departure from the lunar surface. Less fundamental aspects of the LM, like the number of legs and the seating arrangements, required some extra thought. Three legs would have been the lightest arrangement and most adaptable to an undulating terrain, but a failure of any leg would be bad news. Five legs provided excellent stability and safety but the layout conflicted with the arrangement of the tanks for the propellant, and would have necessitated more structure and more mass. Four legs proved to be a suitable compromise.

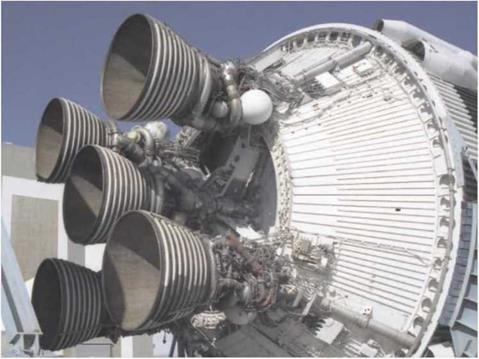

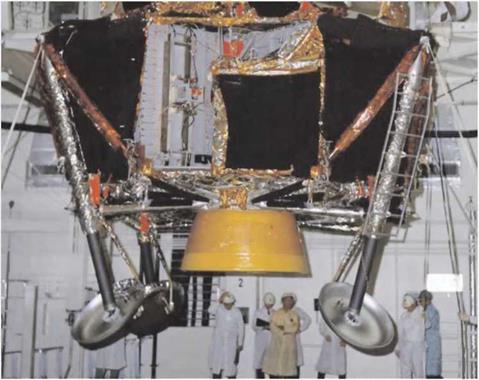

The lower or descent stage was a cross-frame that carried an engine in its centre

|

The descent stage of Apollo 10’s LM during pre-launch processing. (NASA) |

surrounded by four propellant tanks. At each end of the cross-frame, a landing leg was mounted, one of which included a ladder. The bays of the frame between the landing gear were used as stores for the equipment the crews would need when their roles changed from that of spacecraft pilots to lunar explorers, and, on later flights, would provide somewhere to carry a fold-up electric car.

The upper stage of the LM was the crew quarters. Since it would lift the crew off the Moon, it was known as the ascent stage. A pair of propellant tanks protruded like cheeks on either side of a horizontally mounted cylindrical pressure hull, and a small rocket engine was set in the centre of the stage. Early designs for the cockpit included seats and large, high-visibility windows, as in a helicopter. In spacecraft design, there is a tendency for the mass of a spacecraft to rise as engineers go from initial concepts and estimates to final hardware. The Apollo LM could not afford such increases and the constant pressure to minimise the spacecraft’s mass continued even after its first successful mission. Engineers conceived the innovative idea of removing the seats because they realised that a crewman’s legs would make excellent shock absorbers for the low g-forces encountered during descent. Also, in the low gravity of the Moon, standing would be effortless. This change had a profound effect on the layout of the ascent stage. Had the crew been seated, their heads would have been placed well away from the windows and this would have

|

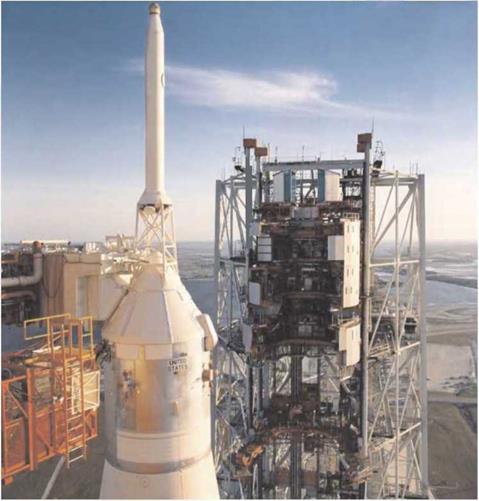

The ascent stage of Apollo ll’s LM during pre-launch processing. (NASA) |

resulted in huge areas of heavy glass to give an adequate field of view. A better solution was to have the two crewmen stand close to the front wall of the spacecraft, where they could look out of two small downward-tilted triangular windows from which they could see an approaching landing site and steer towards it. This arrangement saved a large amount of mass. Major electronics systems were placed to the rear to balance the crew, four sets of thruster packages were placed at each comer for attitude control, and a collection of antennae were mounted on the roof, where function dictated. The result was a remarkable manned spacecraft that was perhaps aesthetically ugly, yet whose form was well matched to the function it had to perfonn.

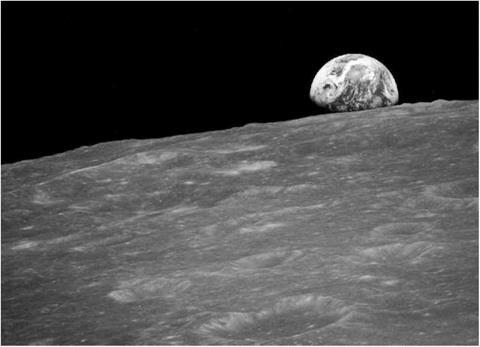

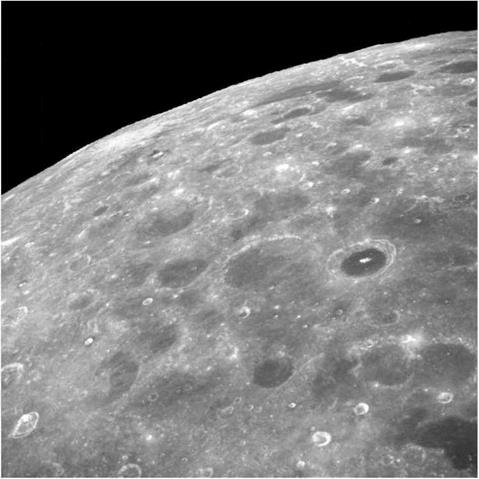

On the morning of 21 December 1968 Frank Borman, Bill Anders and Jim Lovell rode a Saturn V away from Earth to become the first people to swap the Earth’s gravitational hold for that of another world. The three-day long coast out to the Moon gave Jim Lovell plenty of time to practise monitoring the ship’s trajectory by taking sightings of Earth, the Moon and the stars. On 24 December 1968, Apollo 8 took its crew around the lunar far side where they fired its SPS engine to enter lunar orbit to begin 10 revolutions, each lasting two hours. As they coasted 110 kilometres above the cratered surface, the crew closely examined two sites that were being considered for the first landing and, along with tracking stations on Earth, practised techniques for navigating while orbiting the Moon. Much of Earth’s population with access to television watched with amazement when the crew made an extraordinary Christmas-time black-and-white television broadcast made on the penultimate orbit, during which they read the first few verses from the Bible’s Book of Genesis while the stark early morning landscape of the Moon passed in front of the camera.

On the morning of 21 December 1968 Frank Borman, Bill Anders and Jim Lovell rode a Saturn V away from Earth to become the first people to swap the Earth’s gravitational hold for that of another world. The three-day long coast out to the Moon gave Jim Lovell plenty of time to practise monitoring the ship’s trajectory by taking sightings of Earth, the Moon and the stars. On 24 December 1968, Apollo 8 took its crew around the lunar far side where they fired its SPS engine to enter lunar orbit to begin 10 revolutions, each lasting two hours. As they coasted 110 kilometres above the cratered surface, the crew closely examined two sites that were being considered for the first landing and, along with tracking stations on Earth, practised techniques for navigating while orbiting the Moon. Much of Earth’s population with access to television watched with amazement when the crew made an extraordinary Christmas-time black-and-white television broadcast made on the penultimate orbit, during which they read the first few verses from the Bible’s Book of Genesis while the stark early morning landscape of the Moon passed in front of the camera.