THE LAST HURRAH: APOLLO 17

Apollo’s final lunar mission took advantage of behind-the-scenes lobbying by the lunar science community to have a professional geologist visit the Moon. Many of the astronauts, whose backgrounds were usually in the fighter-pilot/test-pilot milieu, believed that a dangerous environment such as an experimental spacecraft in the vicinity of the Moon was just not the place to take someone who was not already inculcated in the philosophies surrounding aviation. Indeed, it was a requirement for the five scientist/astronauts recruited by NASA in 1965 that they learn to fly jets. Only one of them, Harrison ‘Jack’ Schmitt, was a geologist, and he proved a worthy representative when he flew with Eugene Cernan and Ron Evans on the Apollo 17 mission to explore a region of unusually dark soils in a valley near the shores of Mare Serenitatis.

The interest in this site was stirred by A1 Worden’s observations during Apollo 15 of dark halo craters on the floor of the valley which looked like a possible source of continuing lunar volcanism. Apollo 17’s launch on 7 December 1972 was notable by

|

Jack Schmitt, his suit grimy from two days’ work on the Moon, conducts geology at Camelot Crater. (NASA) |

being the only night launch in the programme, with the Saturn V’s fire rising like an artificial sun to illuminate the eastern coast of Florida. To reach the landing site, the spacecraft had to adopt a Moon-bound trajectory that took longer than any previous mission. The subsequent orbital dance around the Moon was the most involved of all the missions. Having landed, Cernan and Schmitt immediately began preparations to exit the LM Challenger, deploy their rover and set up their ALSEP science station. As had Scott on Apollo 15, Cernan had difficulty extracting the deep core drill from the ground, despite having a special jack to aid him in the task. The extra time taken meant that a planned drive to a nearby crater had to be curtailed.

On their second day, during a moonwalk that lasted over 7 ‘A hours, they drove over seven kilometres west to the base of a mountain. Here they sampled boulders whose tracks indicated that they were from outcrops further uphill, thereby enabling the astronauts to collect rock from sites that were well beyond the rover’s reach. On the way back they stopped at a crater that was later named ’Ballet’ because Schmitt lost his footing while sampling, and performed wild gyrations in an attempt to regain his balance.

A frisson passed through those conducting the mission, both on Earth and Moon,

|

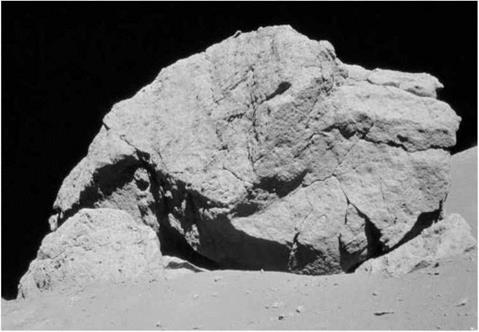

Eugene Cernan and Jack Schmitt’s split boulder. (NASA) |

|

Eugene Cernan at the rover during Apollo’s final moonwalk. (NASA) |

when deposits of orange soil were found on the rim of one of Worden’s dark halo craters. Nothing like it had ever been seen on previous missions, and its colour suggested iron oxidation or rusting, something that normally requires water – a substance notable by its apparent absence on the Moon. Subsequent analysis of the material showed that it was certainly due to volcanism, but of an ancient variety when spectacular fire fountains had sprayed droplets of molten rock hundreds of kilometres into the sky some three billion years ago. It had simply been excavated by the impact that made the crater.

A productive range of stops on the final moonwalk of the Apollo era included a visit by Cernan and Schmitt to another mountain where a split boulder had come to rest. Schmitt’s expert eye spotted the signs of alteration that showed how more than one massive impact had worked and reworked the Moon, and by implication, Earth during their infancy.

Evans, working in the CSM America, was not idle either. The complement of instruments built into the side of his service module had been changed compared to what Apollo 15 carried because its orbit would repeat much of Endeavour s swathe. As with the two previous missions, thousands of high-resolution images of the Moon were taken on giant rolls of film that Evans retrieved during the coast back to Earth by exiting the hatch and manoeuvring hand-over hand along the SM.

The visit of Apollo 17 to a site nearly as grand as Hadley was the peak of a spectacular mission that brought the initial human exploration of the Moon to a highly successful close.

|

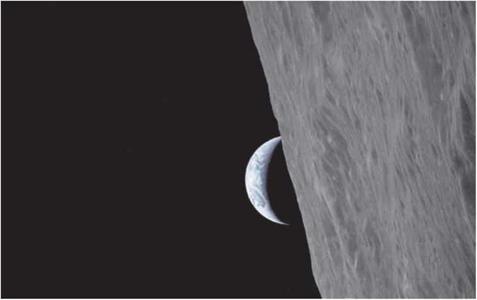

The view of Earth as Apollo 17 came around the Moon. (NASA) |