In a new postwar era of escalating political, social, and technological competition, the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics was not about to be upstaged by its Western rivals when it came to the development of a jet-powered airliner. Adapting a military design for commercial passenger use had been a common theme since the first stodgy biplane transports of the 1920s, and Tupolev’s new swept-wing, twinjet Tu-16 Badger medium bomber provided the perfect airframe from which to develop Russia’s first jet airliner. This new transport would measure 121 feet long with a wingspan of 115 feet and would carry 50 passengers over routes of up to 1,800 miles. Its name would be the Tu-104.

The result of a post-World War II design study to re-establish France’s proud aircraft industry the Caravelle was the world’s first jet aircraft to have its engines mounted on the rear fuselage, beginning the trend that has been adopted by numerous commercial aircraft and business jets alike. The Caravelle made its inaugural flight from Toulouse, France, in April 1955. (Mike Machat Collection)

THE FABULOUS FIFTIES

FLY ME TO THE MOON

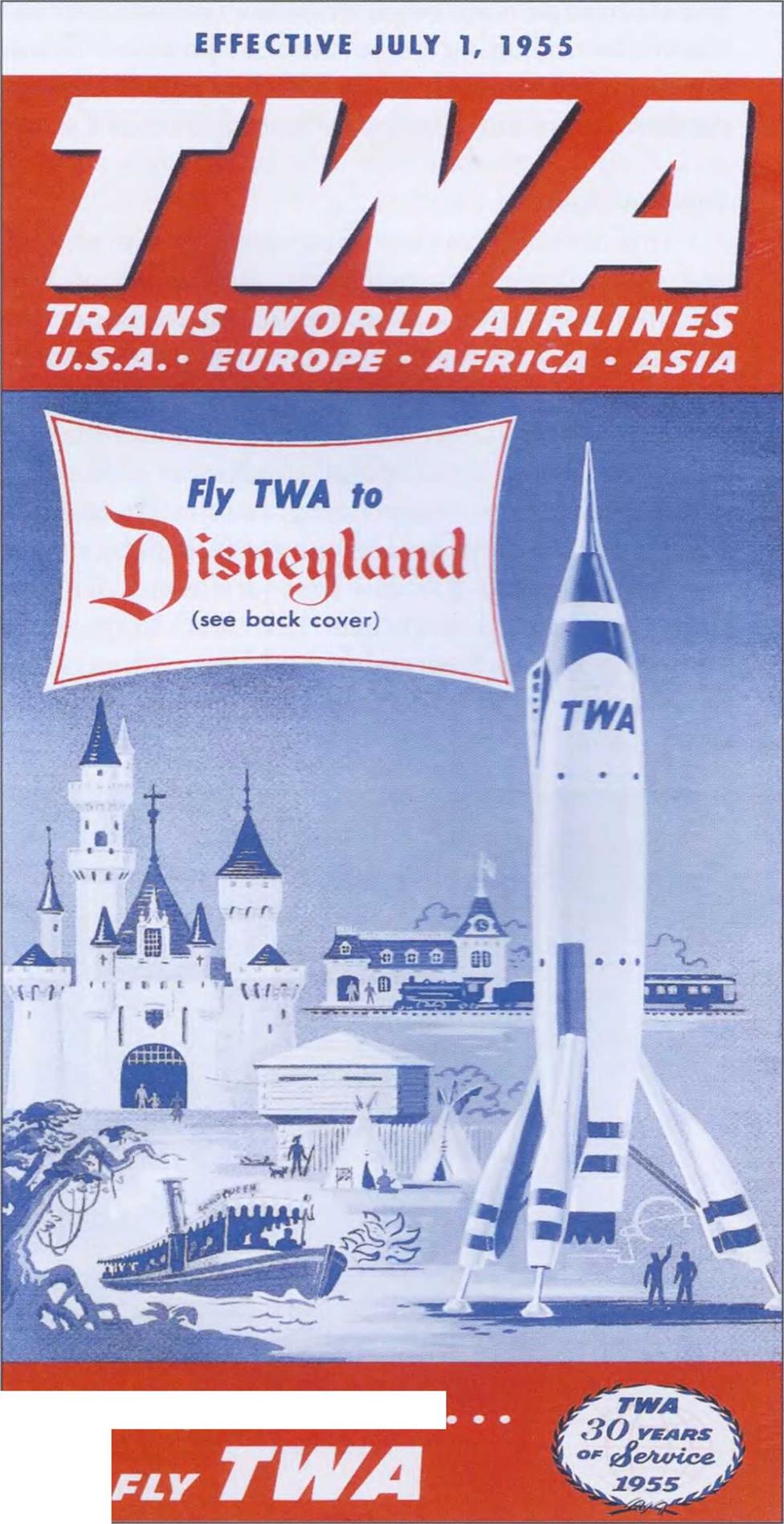

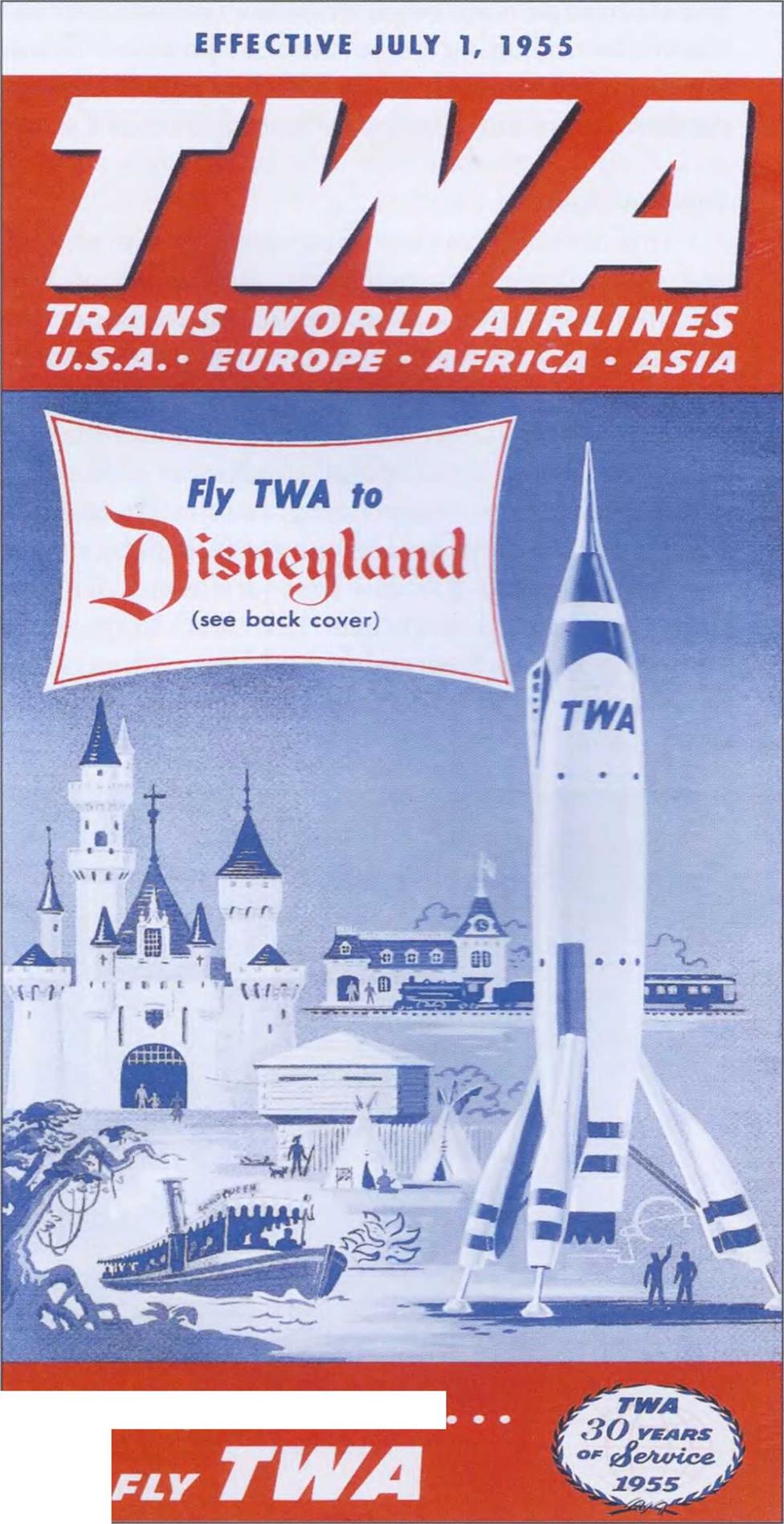

CC nphis is Captain Collins speaking,” says the JL reassuring baritone voice over the ship’s Public Address system. Our stewardess stands at the passenger door clad in the customary uniform of her airline, albeit a bit more futuristic. Everything bespeaks a typical passenger flight. Are we sitting onboard another TWA Constellation flight to New York? Hardly. We are comfortably seated in the passenger cabin of the Star of Polaris at Disneyland in Anaheim, California, in the fall of 1955, and this “spacecraft” is about to take us on a simulated flight to the moon!

CC nphis is Captain Collins speaking,” says the JL reassuring baritone voice over the ship’s Public Address system. Our stewardess stands at the passenger door clad in the customary uniform of her airline, albeit a bit more futuristic. Everything bespeaks a typical passenger flight. Are we sitting onboard another TWA Constellation flight to New York? Hardly. We are comfortably seated in the passenger cabin of the Star of Polaris at Disneyland in Anaheim, California, in the fall of 1955, and this “spacecraft” is about to take us on a simulated flight to the moon!

Not just another ride at an amusement park, the TWA Moonliner in Tomorrowland acted as symbol and substance of the unlimited future world in twentieth-century America. There was absolutely no reason to believe we couldn’t someday have revenue flights into space, just as we could most certainly count on robotically controlled houses and atomic flying cars in the not – to-distant years to come. Walt Disney, ever the visionary and (thankfully) the optimist, always knew to ask “why not?”

Designed by Disney Imagineer John Hench working under the tutelage of rocket scientists Wernher von Braun and Willy Ley, the 76-foot – tall “Rocket to the Moon,” as it was officially known, was actually a one-third-scale model of the real spacecraft envisioned by its creators. The rocket was clad in aluminum sheeting, just like the real thing, although it was structurally like a boiler with its steel skeleton. Early in the planning process as part of Disney’s sense of dynamic marketing, Ralph Damon, president of TWA, was brought into the mix so that the red stripes of Trans World Airlines would be seen flying over the park. A nice touch of believability for Disney, the advertising for the airline was beyond effective. After all, TWA at that time was the official air carrier of Disneyland. As an added bonus, Disney struck another deal, this time with StromBecKer Models to recreate plastic kits of several items from park rides, most notably, the Moonliner. You could purchase one of these kits only a few yards from the real thing, in what was known as Hobbyland, and the new concept of “cross marketing” was born.

Inside the attraction itself, passengers with their mock boarding passes proceeded to a terminal boarding area clad with TWA signage and staging. Here they viewed a TWA “agent” explaining the workings of their rocket and the trip into space using a cutaway model, plus animated films on the spaceport viewing screens. All reference to dates was the year 1986. Inside the passenger compartment now, two more gigantic viewing screens, one above and one below, showed all aspects of our flight. The everpresent voice of Captain Collins, as he narrated our progress and provided scientific knowledge and perspective, reassured us that all this spaceflight business was purely routine and that we would return safely to our launching port unscathed. Passengers on the ride enjoyed the earliest use of air jackhammers and moving seats to heighten the effects and impart realism to the movement and motion of the rocket. This truly was a realistic look at spaceflight, as far as thinking in 1955 went.

Coincident with this attraction, the Disney television program seen on Sunday nights featured a three – part series inspired by a multipart serial in Collier’s magazine, using live actors and plenty of animation. Titled “Man In Space,” one episode borrowed portions of the presentation from the Rocket to the Moon ride at the park. In short, everywhere one looked in the mid-1950s, space exploration was an integral part of our adventure through life. This tugged at the more sobering reality of flying a prop-driven airliner to span the country, which therefore became preparatory to understanding why the future must include commercial jet transports. In the meantime, however, flying to the moon on TWA was just about the most “futuramic” thing a regular person could do.

Coincident with this attraction, the Disney television program seen on Sunday nights featured a three – part series inspired by a multipart serial in Collier’s magazine, using live actors and plenty of animation. Titled “Man In Space,” one episode borrowed portions of the presentation from the Rocket to the Moon ride at the park. In short, everywhere one looked in the mid-1950s, space exploration was an integral part of our adventure through life. This tugged at the more sobering reality of flying a prop-driven airliner to span the country, which therefore became preparatory to understanding why the future must include commercial jet transports. In the meantime, however, flying to the moon on TWA was just about the most “futuramic” thing a regular person could do.

Powered by two Mikulin AM-3 turbojets producing 17,640 pounds of thrust each, the prototype Tu-104 took to the Russian skies for the first time on June 17, 1955. Because so much of Soviet development was shrouded in secrecy behind what the world called “The Iron Curtain,” the Tu-104’s first appearance at London’s Heathrow Airport in March 1956 literally caught the world off guard. While this surprise happenstance was indeed a benchmark in heralding Russia’s presence as a world power, the Soviets upped the ante one year later by placing Sputnik, the world’s first manmade satellite, into orbit around the Earth. This single event radically changed the balance of technological power and launched the Space Race that eventually landed men on the moon and produced today’s International Space Station. (See sidebar “The Fabulous Fifties: Fly Me to the Moon,” page 71.)

By 1959, Aeroflot, Russia’s national airline, had inaugurated Tu-104 service from Moscow to a host of European cities such as London, Paris, Brussels, Prague, Amsterdam, and Copenhagen. In the mother country, Aeroflot’s Tu-104s (and improved 70-passenger Tu-104As) were plying routes between Moscow, Leningrad, and Kiev in the west, and cities as far east as

Vladivostok. International Tu-104 destinations included Cairo, Delhi, Peking, and Pyongyang, although all of the longer-range flights included intermediate stops.

With its cruising speed of 495 mph and passenger capacity of half the later four-engined jetliners, the hefty 160,000-pound Tu-104 will have to be judged by historians as a vital step in the development of the jet airliner rather than a groundbreaking revolutionary design that set the bar for today’s impressive jet fleets. However, those same historians would also have to note that the Tupolev Tu-104 was, in reality, the world’s first jet airliner to conduct sustained-revenue passenger operations after the loss of the de Havilland Comet Is in 1954.

Having entered service in September 1956 and flying continuously until its retirement in 1981, the Tu-104 established an enviable record for safety and reliability for nearly a quarter-century. (This mark is even more impressive considering the severity of the Soviet winter environment.) In final judgment, the sleek twinjet with the distinctive glass bombardier nose section will always be remembered as the aircraft that put Soviet commercial jet operations on the world map.

|

A commercial adaptation of the Soviet Air Force Tupolev Tu-16 Badger bomber, the Tu-104 was the Soviet Union’s first jet airliner, and entered into commercial service before either of America’s first two jetliners, the 707 and DC-8, had even flown. (Mike Machat Collection)

|

|

![]()

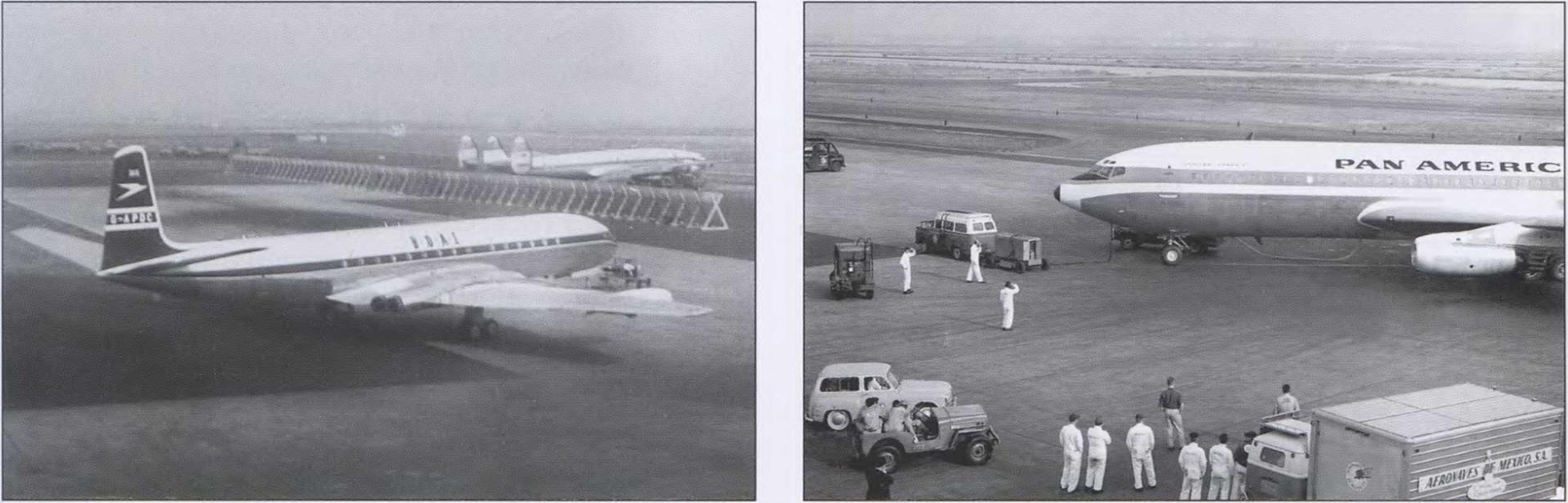

Complete with all the associated pomp and circumstance, Pan American’s first Boeing 707 service from New York to Paris prepares to receive its passengers at Idlewild on a rainy autumn night, October 26, 1958. Although a BOAC Comet 4 snuck under the wire two weeks earlier to beat the 707 to the punch inaugurating the world’s first transatlantic jet service, Pan Am

Complete with all the associated pomp and circumstance, Pan American’s first Boeing 707 service from New York to Paris prepares to receive its passengers at Idlewild on a rainy autumn night, October 26, 1958. Although a BOAC Comet 4 snuck under the wire two weeks earlier to beat the 707 to the punch inaugurating the world’s first transatlantic jet service, Pan Am

CC nphis is Captain Collins speaking,” says the JL reassuring baritone voice over the ship’s Public Address system. Our stewardess stands at the passenger door clad in the customary uniform of her airline, albeit a bit more futuristic. Everything bespeaks a typical passenger flight. Are we sitting onboard another TWA Constellation flight to New York? Hardly. We are comfortably seated in the passenger cabin of the Star of Polaris at Disneyland in Anaheim, California, in the fall of 1955, and this “spacecraft” is about to take us on a simulated flight to the moon!

CC nphis is Captain Collins speaking,” says the JL reassuring baritone voice over the ship’s Public Address system. Our stewardess stands at the passenger door clad in the customary uniform of her airline, albeit a bit more futuristic. Everything bespeaks a typical passenger flight. Are we sitting onboard another TWA Constellation flight to New York? Hardly. We are comfortably seated in the passenger cabin of the Star of Polaris at Disneyland in Anaheim, California, in the fall of 1955, and this “spacecraft” is about to take us on a simulated flight to the moon!

Coincident with this attraction, the Disney television program seen on Sunday nights featured a three – part series inspired by a multipart serial in Collier’s magazine, using live actors and plenty of animation. Titled “Man In Space,” one episode borrowed portions of the presentation from the Rocket to the Moon ride at the park. In short, everywhere one looked in the mid-1950s, space exploration was an integral part of our adventure through life. This tugged at the more sobering reality of flying a prop-driven airliner to span the country, which therefore became preparatory to understanding why the future must include commercial jet transports. In the meantime, however, flying to the moon on TWA was just about the most “futuramic” thing a regular person could do.

Coincident with this attraction, the Disney television program seen on Sunday nights featured a three – part series inspired by a multipart serial in Collier’s magazine, using live actors and plenty of animation. Titled “Man In Space,” one episode borrowed portions of the presentation from the Rocket to the Moon ride at the park. In short, everywhere one looked in the mid-1950s, space exploration was an integral part of our adventure through life. This tugged at the more sobering reality of flying a prop-driven airliner to span the country, which therefore became preparatory to understanding why the future must include commercial jet transports. In the meantime, however, flying to the moon on TWA was just about the most “futuramic” thing a regular person could do.

With the original Caravelle cockpit and nose section having been literally grafted onto the fuselage from Britain’s de Havilland Comet, French engineers at Sud-Est realized that a modernization was required as the aircraft became more advanced in the early 1960s.

With the original Caravelle cockpit and nose section having been literally grafted onto the fuselage from Britain’s de Havilland Comet, French engineers at Sud-Est realized that a modernization was required as the aircraft became more advanced in the early 1960s.