The Learning Curve

With every major step forward in aviation comes a learning curve in the form of incidents and accidents from which new aircraft design features and operational procedures emerge to prevent recurrences. It is an unfortunate but inevitable step in the advancement of progress during which valuable machinery and precious lives are lost, but life-saving improvements in safety and performance are the valuable results of this process. Perhaps only in retrospect can we understand just how safe and reliable today’s modern airliners have become. Unlike in the early 1960s, it is now a rarity to have a news bulletin suddenly interrupt a radio or TV program blaring out that there was another major airliner crash with the loss of all onboard.

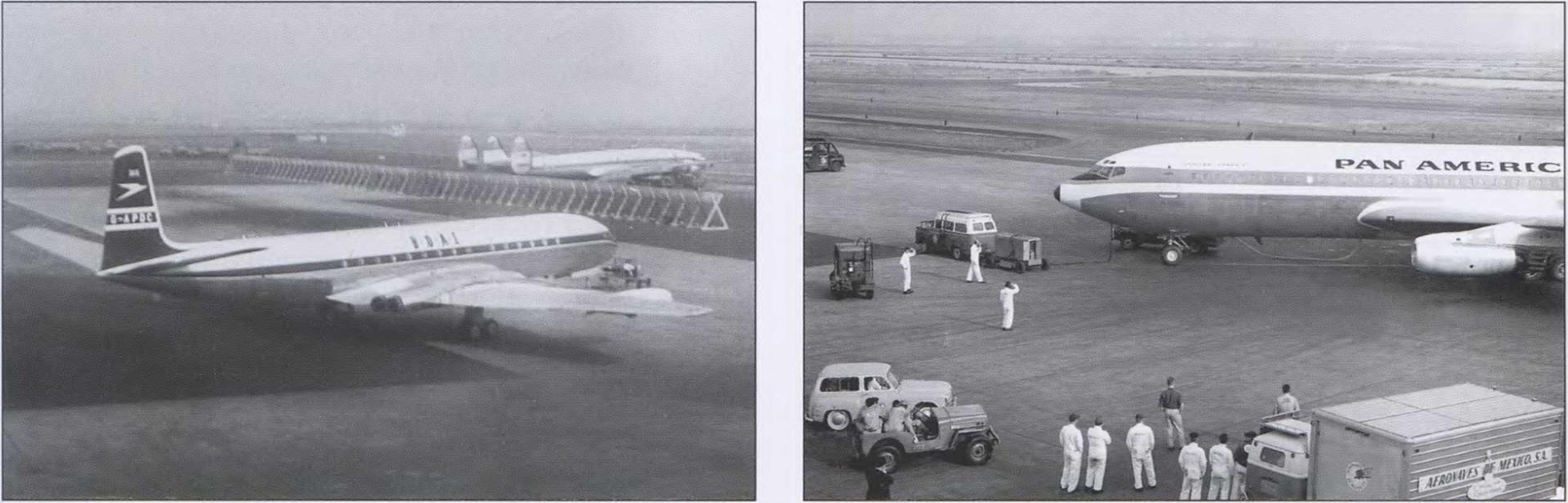

Complete with all the associated pomp and circumstance, Pan American’s first Boeing 707 service from New York to Paris prepares to receive its passengers at Idlewild on a rainy autumn night, October 26, 1958. Although a BOAC Comet 4 snuck under the wire two weeks earlier to beat the 707 to the punch inaugurating the world’s first transatlantic jet service, Pan Am

Complete with all the associated pomp and circumstance, Pan American’s first Boeing 707 service from New York to Paris prepares to receive its passengers at Idlewild on a rainy autumn night, October 26, 1958. Although a BOAC Comet 4 snuck under the wire two weeks earlier to beat the 707 to the punch inaugurating the world’s first transatlantic jet service, Pan Am

|

|

|

|

|

|

Saturday, October 4, 1958, saw the world’s first two jet airliners together for the very first time at New York International Airport. On the observation deck of the International Arrivals Building a crowd of nearly a thousand spectators greeted the BOAC Comet that had just flown the world’s first commercial revenue passenger service across the Atlantic in a jet transport. Not to be outdone, Pan Am’s Juan Trippe ordered one of his new 707s, in New York that day on a route-proving flight, to be parked at the adjoining gate when the Comet arrived from London. The 707 simply dwarfed the smaller British jet, its fuselage polished to a mirror finish. Excitement filled the air along with the new scent of kerosene, and the piercing jet-engine noise was simply deafening. No one in attendance really cared, however, for this was the moment that signaled the official start of the Jet Age. (Sykes Machat photos)

As the first new jets entered service in 1958 and 1959, they were flown by seasoned airline veterans considered by their companies to be the “best of the best” in terms of piloting skill and ability to command a $5 million aircraft with up to 150 souls on board. New onboard systems, powerplant management, flight characteristics, and operating procedures had to be learned, and emergency procedures were practiced incessantly, committed to memory, and then mastered in the air. With this new breed of airliners, jet-age training and methodology was required to bring its veteran prop-era pilots up to speed. Classroom training could only go so far, however, and because full-motion simulators had not yet come into the ground training fleet, real aircraft were taken off the line and used for flight crew assimilation and pilot checkouts.

February 3, 1959, was a particularly black day in aviation history. On that cold winter evening, American Airlines’ first Lockheed Electra —an airplane in service for only 10 days —crashed into the upper East River while on approach to New York’s LaGuardia Airport. In Clear Lake, Iowa, that night, a chartered Beechcraft Bonanza crashed on takeoff killing rock-and-roll legend Buddy Holly and fellow rockers Ritchie Valens and “The Big Bopper.” Midway over the North Atlantic on a routine passenger flight from Paris to New York that same evening, a Pan American Boeing 707-120 experienced autopilot failure while flying at cruise altitude, causing commercial aviation’s first recorded “jet upset” where the airplane unexpectedly departed straight-and-level flight and plunged 29,000 feet toward the ocean.

Miraculously, the crew of the Boeing 707-120 was able to wrestle the controls and pull out of the nearly inverted dive a scant 6,000 feet above the waves, thankfully saving all onboard including famed American dance legend, Gene Kelly. In testimony to the big Boeing’s rugged construction, the airplane held together through the ordeal, but suffered minor structural damage as a result of heavy g-loads induced during the recovery. And speaking of recovery, only three weeks later, another Pan Am 707 shed an entire engine and pylon during a minimum-control airspeed demonstration while on a training flight from Le Bourget Field in Paris. The crew managed to regain control and land at London’s Heathrow Airport where Pan Am had better maintenance facilities than at Paris.

The learning curve also applied to the news media and how they dealt with Jet Age emergencies. In July that same year, another Pan American 707 lost two wheels from its left main landing gear while taking off from New York and, after burning off enough fuel, returned to Idlewild Airport to make a successful emergency landing on a foamed runway. Unbeknown to airport authorities, however, news of the impending emergency was being broadcast “live” via local TV and radio stations. By the time the crippled jet landed, a crowd of more than 50,000 curious onlookers had invaded the airport grounds in order to see the expected crash. They stood literally by the side of the runway, much to the chagrin of rescue crews trying to reach the jetliner!

In August, the first fatal training accident of the Jet Age occurred when an American Airlines 707-120 rolled inverted at low altitude and crashed into a field after executing a two-engine-out missed approach to Calverton Airport on eastern Long Island. The practice crew of three pilots and two flight engineers were killed. Similar training accidents claimed a Braniff 707 later that same year, a Delta Convair 880 in 1960, a TWA 880 and another American 707 in 1961, and a Western Airlines Boeing 720B in 1963. These tragic losses made a compelling case for the development of more-sophisticated cockpit simulators to replace inflight training whenever possible.

By the end of 1962, operational turbine-powered airliners that crashed while in passenger service included a United DC-8 in Brooklyn (midair collision), an Eastern Electra in Boston (bird ingestion on takeoff), a Braniff Electra in flight over Texas (wing separation), an Aeronaves de Mexico DC-8 in New York (runway overrun), a Northwest Electra in flight over Indiana (wing separation), a United DC-8 in Denver (emergency landing), an American 707 at New York (rudder malfunction on takeoff), a Sabena 707 on landing at Brussels, Belgium, an Alitalia DC-8 landing in Bombay, India, a Varig 707 landing in Lima, Peru, and two Air France 707s —one on approach to Paris and the other landing in bad weather at Guadeloupe, West Indies.

When examined in historical perspective, these 18 accidents exacted an exceedingly high toll in terms of human life and machinery lost. However, because they occurred at the beginning of the learning curve, significant knowledge was amassed and equally significant improvements were made in aircraft design, operating procedures, and even air-traffic control. For instance, leading-edge slats and other high-lift devices were added to the Boeing 707, allowing lower landing speeds and better maneuverability. Ventral fins were also added to the 707 to allow greater inherent stability at low speeds and high angles of attack during landing. To reduce the risk of midair collisions, aircraft speeds were reduced to a 250-mph maximum below 10,000 feet.

As other lessons were learned from subsequent accidents and incidents over the years, continual improvements in airframe and powerplant design, onboard systems technology, and operational procedures were made that eventually led to the impressive safety record we enjoy for all types of commercial airliners today.

|